Last September, I watched a fourth-year student close her laptop after yet another program info session. She’d just stepped out of the infusion center that morning, slapped on some concealer, and now she was trying to decide: do I tell programs about my disease, or keep it quiet and pray I do not flare on interview day? She looked exhausted—not from medicine, but from managing medicine and her own body like a second full‑time job.

If that sounds familiar, you are not “overthinking it.” You’re dealing with two hard problems at once: the residency match and a chronic illness that does not care about ERAS deadlines. Let’s walk through how to handle both without burning yourself to the ground.

1. First, Get Honest About Your Reality (Not Your Fantasy Schedule)

Before you touch ERAS or start drafting a single personal statement, you need a blunt, private inventory of your actual limits.

Not your “good week” self. Your baseline. And your flare self.

Ask yourself and write it down somewhere you won’t show anyone:

- What specifically triggers flares or worsens my symptoms?

(overnight calls, stress, missed meals, heat, infection, long OR days, standing, high volume clinics, etc.) - Which tasks are hardest on my body/mind?

(fine motor work, long procedures, constant lifting, EMR marathons, driving distance) - How often do I need medical follow‑up, treatment, or infusions?

- What does a bad month look like? How many days are you partially or fully limited?

- How predictable or unpredictable is this?

Now cross‑reference this truth with reality of different specialties. You do not need perfection; you need tolerable misalignment.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Surgical subspecialties | 95 |

| Emergency Medicine | 85 |

| Ob/Gyn | 80 |

| Internal Medicine | 65 |

| Psych/Family Med/PM&R | 45 |

This is relative, not absolute, but you get the idea: the more physically punishing and schedule‑chaotic the field, the more your body will tax you for it. Some people with chronic illness still pick surgery or EM. But they go in with eyes wide open and contingency plans, not denial.

If you’re already dead on your feet with M3 rotations and Step 2, a lifestyle‑heavier field might be survivable on paper but brutal in practice. Be honest.

2. Strategic Specialty and Program Selection When You’re Not 100% “Reliable”

You’re not unreliable. You’re dealing with physiological unpredictability. Programs, however, care about coverage and call.

So you pick your battlefield.

Choosing a specialty that won’t chew you up

You want to bias toward specialties that:

- Have more predictable schedules

- Offer outpatient or consult‑heavy tracks

- Can be done part‑time or with flexible practice options after training

- Have less mandatory heavy lifting or standing for 8–12 hours straight

Typically more forgiving (depending on your specific illness):

- Psychiatry

- Outpatient‑heavy Family Medicine

- Outpatient Internal Medicine / primary care tracks

- PM&R

- Pathology

- Radiology (depending on sitting tolerance, back pain, etc.)

- Some fellowships later (allergy, rheum, endo, heme/onc) if IM is doable

Tougher but not impossible:

- Ob/Gyn

- Emergency Medicine

- Hospitalist‑heavy IM

- Pediatrics (especially inpatient, NICU)

Brutal for many chronic illness patterns:

- General surgery and most surgical subspecialties

- Ortho

- Neurosurgery

- ENT (depending on your particular limitations, but OR hours are real)

This isn’t “you can’t.” It’s “you will pay more for this choice—are you willing, and can you buffer that cost?”

Choosing programs with survivable culture and logistics

Most students with chronic illness do not appreciate how different programs’ cultures are until they’re trapped in one.

You want to find:

- Programs that explicitly talk about wellness and back it up with structure

- Larger programs with more residents (better coverage when someone is out)

- Strong outpatient tracks/fellowship pipelines if you’re aiming clinical but lighter on overnights

- Reasonable call schedules, night float systems instead of q4 28‑hour calls

- Locations near your specialists or at least in a city with robust healthcare

- “Old school” vibe, bragging about how tough they are

- Residents casually joking about never seeing the sun, 90‑100 hour weeks, or “we eat our young”

- Programs in rural areas where seeing your subspecialist means a 3‑hour drive

- Programs that look at you weird if you ask a basic question about sick day policies

Use Q&A time during virtual sessions. Ask current residents (privately if you can find them via alumni or social media) direct questions:

- “If a resident is hospitalized or has a flare, how is that usually handled?”

- “How hard is it to get a doctor’s appointment scheduled during residency?”

- “What happens if someone has a temporary disability or needs accommodations?”

You’re not asking them to diagnose you. You’re testing their culture.

3. To Disclose or Not to Disclose: Where, When, and How

This is the part everyone agonizes over. There is no perfect answer, but there are wrong moves.

Places disclosure can come up

- ERAS application

- Personal statement

- MSPE / Dean’s letter

- Letters of recommendation

- Interviews (questions and casual conversation)

- Post‑match / after you’ve signed a contract

Let’s break strategy.

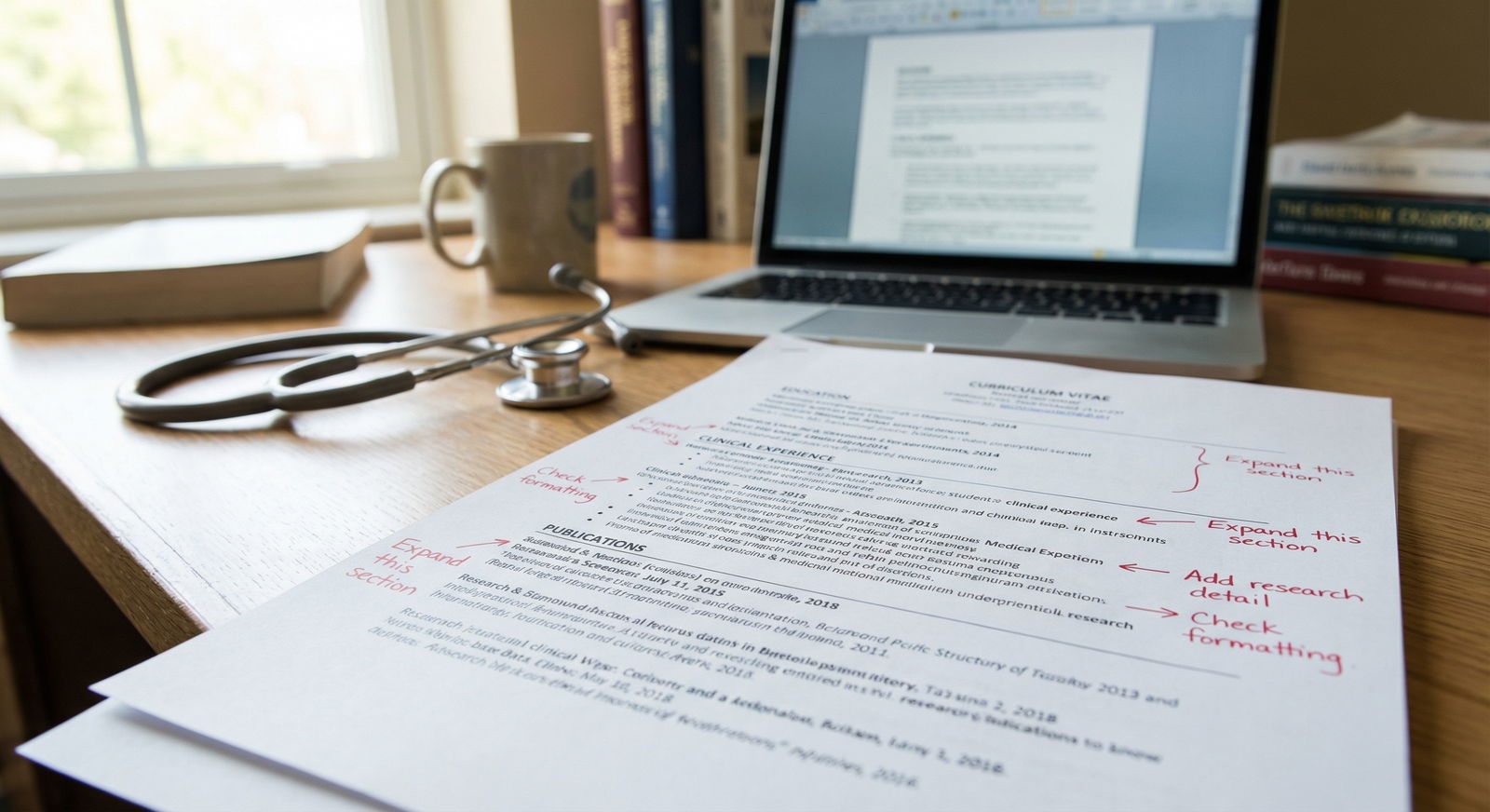

ERAS and personal statement

General rule:

You disclose in your application if:

- It explains a red flag (LOA, extended time, a bad semester/Step score drop) and

- You can show how you’re stable, safe, and functional now.

You do not disclose if:

- It won’t change how they interpret your application

- It just adds risk in their mind without upside for you

If you must address it (for a leave of absence, big Step score drop, large gap), keep it concrete and controlled:

Bad version:

“I have lupus which causes debilitating flares, fatigue, and frequent infections…”

Better version:

“During my second year, I was diagnosed with a chronic autoimmune condition that required a brief leave for diagnosis and treatment optimization. Since then, with consistent therapy, I’ve had stable health and completed all clinical rotations on schedule, including full call responsibilities.”

You give:

- Minimal labels

- Specific impact

- Clear arc: problem → treatment → current stability + evidence

You do not need to name the disease in ERAS or your PS unless you want to. “Chronic autoimmune condition” or “chronic health condition” is often enough.

MSPE and letters

If your school already documented your leave or accommodations, it may already be “out there” in coded language like “extended program.” That’s fine. You still control whether to give context in your personal statement or supplemental application.

Do not let a letter writer overshare. Tell them explicitly:

- “Please do not mention my specific diagnosis.”

- “If you reference my leave, I’d appreciate you framing it in context of how I performed afterward.”

If they can’t respect that, pick another writer.

Interviews: what to say when they poke at gaps

Sometimes they’ll ask: “I noticed you took a leave/extra time. Can you tell me about that?”

You are not obligated to disclose intimate medical details. A tight script works best:

“During my second year I had a health issue that required a brief leave for evaluation and treatment. Things have been stable for over X years now, and I’ve been able to complete all my clinical rotations and call without restrictions. It ended up teaching me a lot about navigating the healthcare system from the patient side, which has honestly made me a more empathetic clinician.”

Then shut up. Do not ramble. If they push for diagnosis, you can say:

“I’d prefer to keep the specific diagnosis private, but I’m happy to talk about how I’ve managed it and how it has (or hasn’t) affected my training.”

If they keep pressing, that’s a data point. Do you really want to train there?

4. Accommodations: What You Can Realistically Ask For (And When)

A lot of students confuse disability rights with unlimited flexibility. That’s not how it works in residency.

You have two overlapping but different worlds:

- Legal protections (ADA, etc.) – you can’t be discriminated against solely for disability, and you can request reasonable accommodations.

- Program requirements – ACGME/core specialty boards require certain clinical exposure and competencies.

What “reasonable” usually looks like in residency

These tend to be on the table:

- Ergonomic adjustments (chairs, standing desks, special stools in the OR)

- Schedule tweaks around predictable treatment days (e.g., chemo or infusion days)

- Permission to sit more often, use mobility aids, or take short breaks for blood sugar/meds

- Avoiding specific non‑essential tasks that are uniquely difficult for you (for example, heavy lifting if you have severe back disease, as long as core duties are covered)

- Help rearranging rotation order to cluster more intense months when you’re typically more stable (if your condition is seasonal, etc.)

These are much harder to get:

- No nights at all in fields where nights are core (EM, surgery, OB)

- Dramatically reduced hours compared with your cohort for long stretches

- Skipping entire types of core rotations

- A fully part‑time residency spot (rare in the US, though some programs will consider 80% schedules with extended training length—very program‑dependent)

When to disclose for accommodations

You typically do not negotiate accommodations during interviews. That’s risky and too early.

Instead:

- Before ranking: Informally assess culture through resident chatter, conferences, and how PDs talk about wellness and prior residents with health issues.

- After you match, before you start: Reach out to GME/HR and the program director to initiate a formal accommodations process if you’ll need one on day one.

- If things change: If you flare or decompensate during residency, you can always open this conversation later.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | MS4 with Chronic Illness |

| Step 2 | Decide on Specialty & Program Type |

| Step 3 | Limited Disclosure in ERAS/PS |

| Step 4 | Keep Health Private in Apps |

| Step 5 | Interview with Prepared Script |

| Step 6 | Rank Programs Based on Culture |

| Step 7 | Match Day |

| Step 8 | Contact GME/PD for Accommodations if Needed |

| Step 9 | Need to Explain Red Flags? |

You’re playing a long game. Don’t blow your cover early or martyr yourself later.

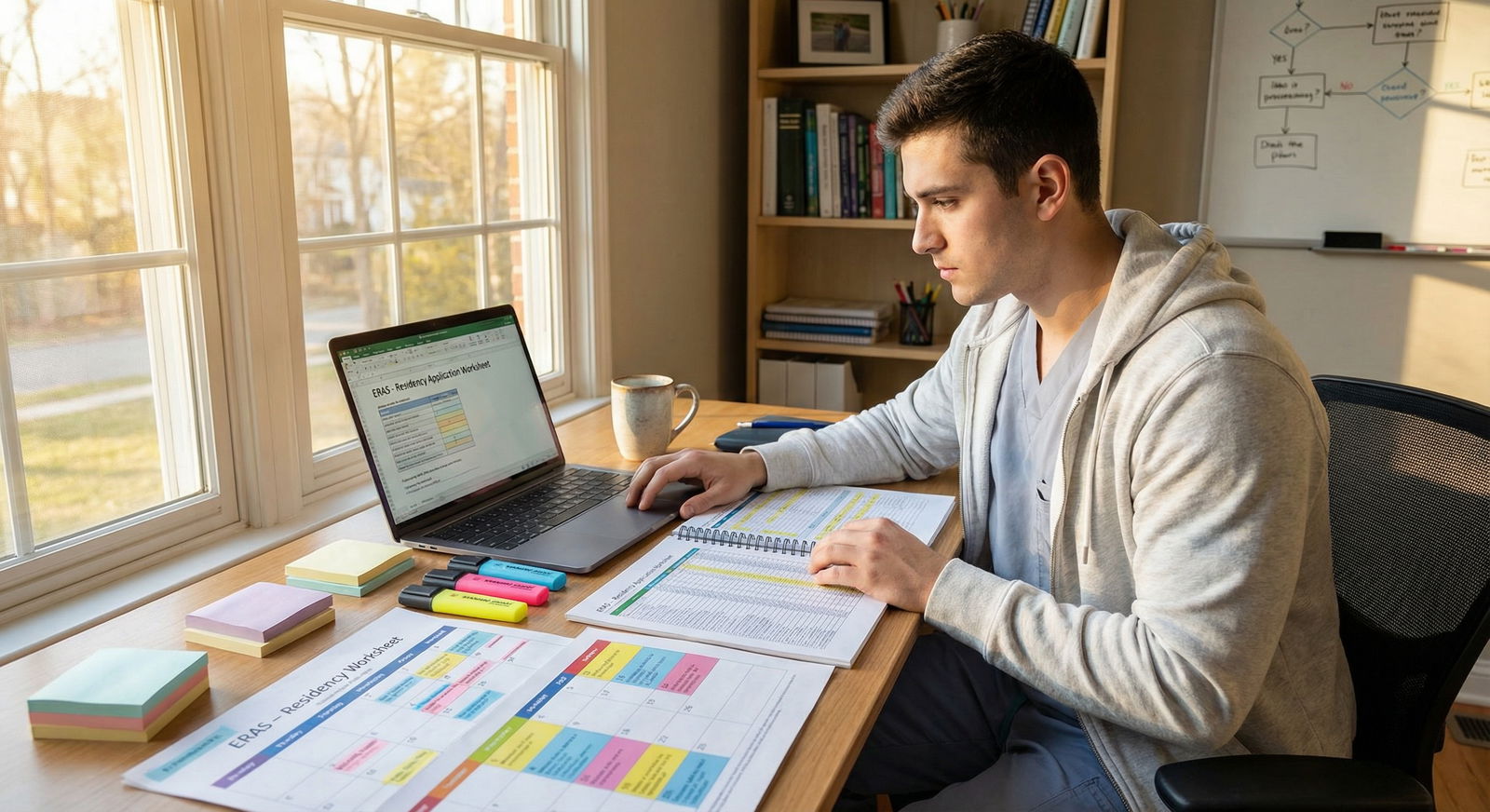

5. Managing the Application Season Without Triggering a Flare

You already know this, but I’ll say it anyway: ERAS + 4th year + chronic illness is a setup for a crash if you treat yourself like a healthy 25-year-old with infinite reserve.

So build the season around your body’s realities.

Front‑load and slow‑drip the heavy work

You want less chaos during peak flare windows. That means:

- Start personal statement drafts early (Spring M3 / early M4)

- Request letters before everyone else floods attendings with requests

- Pre‑build your ERAS “Activities” and descriptions before the portal even opens

- Use templates for program‑specific paragraphs so you’re not reinventing the wheel

You’re trying to avoid doing critical thinking work while febrile, post‑treatment, or exhausted.

Be ruthless about interview scheduling

You do not have to say yes to every proposed day.

- Cluster interviews by geography when in‑person (if that returns) to avoid endless travel

- For virtual interviews, don’t stack 5 intense days in a row if you know that will wreck you

- Try to avoid scheduling interviews directly after infusion, chemo, or procedures, unless you know you bounce back quickly

And—it needs to be said—plan for at least one interview day where your body betrays you. Have backup:

- Outfit that’s comfortable even with pain/bloating

- Simple backup makeup/hair plan if you wake up wiped

- Pre‑written “I’m having a mild medical issue; can we shift to later in the day/another date?” email to coordinators if you absolutely cannot function

Protect the basics like they’re meds

When you’re in application mode, the first things people cut are the things holding their body together: sleep, meds on time, movement, actual meals.

You do not have that luxury.

Anchor rules (non‑negotiables):

- Medications on time, every time (set alarms; build them into your schedule like rounds)

- At least some real food before each interview (even if it’s just toast and peanut butter)

- Hard bedtime on nights before interviews (you can cram after the season, not before)

This is not idealized wellness talk. This is: “Do I want my brain to work during the one hour that might decide my next three years?”

6. Talking About Your Illness Without Making It Your Whole Personality

Some of you do want to frame your personal statement around your illness. Fine. But you need to do it with precision.

Programs have two quiet fears when they see chronic illness in an application:

- “Will this person be out a lot and leave the team short?”

- “Are they psychologically resilient enough for residency, or will this break them?”

You need to answer those questions without sounding defensive.

How to frame it if you include it in your story

Origin – brief, no drama.

“During my third year, I developed X symptoms and was eventually diagnosed with a chronic inflammatory condition.”Impact – specific, limited.

“This required a brief leave and adjustment of my medications.”Adaptation – concrete, not vague growth-speak.

“I learned to pre‑plan my schedule around my infusion days, communicate clearly with my teams, and still meet the expectations of my rotations.”Current status – functional and time‑stamped.

“My disease has been stable for over two years. I’ve completed all rotations, including night float and ICU, without any additional time or restrictions.”Value add – how it changed your clinical lens.

“Sitting on the other side of the stretcher gave me a visceral understanding of what it means to trust a healthcare team, which directly shapes how I communicate with my own patients.”

You are not asking for pity. You’re showing: “I’ve already been stress‑tested. I know how to function with this. You’re not taking on an unknown.”

If you cannot honestly claim stability yet, be more conservative about disclosure and focus on your care plan and insight rather than pretending you’re fixed.

7. Worst-Case Planning: If Things Go Sideways During Training

I’d love to tell you that if you prepare well, nothing will go wrong. You know better. Bodies do what they want.

So you quietly line up your “break glass in case of emergency” plan.

Before you even start residency

- Know your institution’s process for medical leave and disability accommodations

- Identify a local PCP and, ideally, a specialist before orientation month

- Clarify your health insurance, coverage for meds/infusions, and prior auth nonsense

| Role | Why You Need Them |

|---|---|

| Primary Care Physician | Coordinate routine care, referrals |

| Specialist (e.g., Rheum) | Manage core chronic illness |

| GME Office Contact | Accommodations, leave, policy questions |

| Program Director/APD | Schedule, rotation, performance decisions |

| Trusted Senior Resident | Practical day-to-day advice, backup |

If you start to spiral

Signs things are slipping:

- You’re needing urgent care/ED more often

- You’re missing work days recurrently

- You’re barely holding on cognitively from fatigue/pain

- Feedback from seniors/PDs mentions “reliability,” “stamina,” “concern about ability to complete training”

This is when many residents panic and go into hide mode. That’s the worst move.

Instead:

- Loop in your doctor(s) and get objective documentation.

- Talk to your PD early, not after you’ve missed 8 shifts. Phrase it like:

“I’m noticing my health is impacting my performance more than expected. I’m working with my doctors to stabilize things. Are there temporary adjustments we can consider while I get this under better control?” - If needed, involve GME/HR for formal accommodations or medical leave.

Yes, this is scary. But if you handle it proactively, you’re much more likely to preserve your relationship with the program and protect your ability to finish.

8. How to Decide Where to Rank When You’re Balancing Dream vs. Health

Your rank list is not about impressing classmates. It’s about where you can survive and grow.

You’re weighing three main variables:

- Fit with specialty and program culture

- Geographic proximity to your care network (or quality of new options)

- Realistic workload vs. your medical capacity

Think of each program in terms of “Will this place help me have a career, or just a fancy name and a broken body?”

If Program A is top‑10 name, malignant culture, 80–90 hour weeks, far from your specialist… and Program B is mid‑tier university hospital, supportive, 60–70 hours, across town from your infusion center…

Rank B above A. Every time. Prestige does not refill your tank when you’re on call at 3am and your joints are on fire.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Program A | 9,3 |

| Program B | 6,9 |

| Program C | 7,7 |

| Program D | 5,8 |

| Program E | 8,4 |

(X-axis = prestige, Y-axis = sustainability. You want programs in the top‑right quadrant; if you must choose, go up, not right.)

FAQ (Exactly 5 Questions)

1. Should I ever explicitly name my diagnosis in my application?

Sometimes. If it’s a well‑understood condition with a clear treatment path and you’re now stable (for example, well‑controlled Type 1 diabetes, celiac disease, ulcerative colitis in remission), naming it can decrease mystery and stigma. If it’s something heavily misunderstood or weaponized (certain psychiatric conditions, complex autoimmune disorders without clear control yet), you may be better off using more general language like “chronic autoimmune condition” and focusing on function and stability, not labels.

2. Will disclosing my illness automatically hurt my chances of matching?

No, not automatically—but it can shrink your safety net if you do it poorly or too broadly. Programs can’t legally say, “We’re rejecting you because you’re sick,” but they can say, “We’re worried about coverage and training completion.” That’s reality. If you choose to disclose, do it surgically: only where it explains something that would otherwise look worse (gaps, leaves, big score drops) and always paired with clear evidence and time‑stamped stability.

3. How many programs should I apply to if I have a chronic illness?

Err on the side of more—but within reason for your specialty. You want enough programs to offset any unconscious bias or concern, especially in competitive fields. For example, if a typical solid applicant in your specialty would apply to 35–40 programs, you might aim for 45–55, weighted toward places with reputations for supportive environments. Do not triple your list and then kill yourself with 30 interviews you can’t physically handle. Volume helps, but smart targeting matters more.

4. What if I flare badly right before or during an interview?

If you wake up truly non‑functional, email the coordinator as soon as you can. Something like: “I’m experiencing an unexpected acute medical issue today and am not at my best. Would it be possible to reschedule my interview? I’m very interested in your program and want to be fully present.” Most programs will accommodate at least once. If you flare mid‑day but can function, focus on looking engaged and grounded, not perfect. Camera off briefly between sessions, hydrate, meds as prescribed. Programs care more about your overall demeanor than whether you look slightly washed out.

5. Can I change specialties later if I realize my body can’t handle my current one?

Yes, but it’s not fast or guaranteed. People do switch—surgery to PM&R, EM to psychiatry, OB to FM. It usually involves frank discussion with your PD, sometimes completing a year in your current field, and then reapplying or pivoting into an open PGY‑2 spot. Chronic illness can be a legitimate reason. But you’re better off making a realistic choice up front than banking on a switch. Plan as if you’re stuck with your first choice. Choose the one your body can live with, not the one that only your ego wants.

Key points to walk away with:

- Be brutally honest about your limits and pick a specialty and programs that will not chew you up faster than you can heal.

- Disclose only what helps you, and when you do, focus on function, stability, and the systems you’ve built—not on the drama of the illness.

- Build your entire application season and rank list around one question: “Where can I reliably show up, grow, and still have something left of myself at the end of training?”