The worst way to handle a family crisis on your residency application is to act like it never happened.

If a real crisis delayed your graduation, programs are not scared of the delay itself. They’re scared of what it might mean: poor professionalism, academic failure, instability, ongoing chaos. Your job is to make sure they see: this was a defined crisis, you handled it as an adult, and you are now fully ready to train.

Let’s walk through exactly how to do that.

1. First, be honest about what programs actually worry about

You’re not being “red-flagged” just because you took an extra semester or year. People take time for babies, chemo, dying parents, mental health, military service. PDs know this.

What does raise red flags is when:

- The story keeps changing between ERAS, personal statement, and LORs

- The explanation is super vague (“personal reasons,” “life circumstances”)

- The crisis seems ongoing with no clear resolution

- Your performance never recovered afterward

- You sound bitter, defensive, or like you blame everyone but yourself

Your goal is simple: show this was a time‑limited, specific, and now-resolved situation, and that your performance after the crisis backs that up.

If you do that, most programs will move on in about 5 seconds.

2. Decide where to address the delayed graduation (and how much)

Do not scatter half-versions of the story everywhere. You need a unified, consistent approach.

Here’s where this usually comes up:

| Location | How Much Detail | When To Use It |

|---|---|---|

| ERAS Experiences section | 1–2 concise lines | If crisis connects to maturity or responsibilities |

| ERAS 'Education/Leaves' area | Brief factual note | Always, if school documented delay/leave |

| ERAS 'Additional Information' | 2–5 sentences | Ideal primary place for explanation |

| Personal Statement | Short paragraph max | Only if crisis shaped your path or specialty |

Baseline rule

Use ERAS Additional Information (or the equivalent free-text section) as your main explanation. Everywhere else, be briefer and consistent.

3. Build your core explanation: the three-part structure

If you’re in this situation, stop guessing. Use this structure and tighten it to your facts.

Your explanation needs three parts:

- What happened – specific enough to be real, not so detailed it becomes trauma porn

- What you did – concrete actions, not “I grew a lot” fluff

- Where you are now – stability, recovery, and evidence of readiness

Think of it as: Event → Response → Resolution.

Here’s a solid template you can adapt:

“During my third year of medical school, my [close family member] developed a [brief description: e.g., ‘sudden, life‑threatening illness’]. I took a [X‑month] leave of absence to serve as their primary support and coordinate medical care. This resulted in a delayed graduation by [X months/year].

After returning, I completed all remaining clerkships and requirements, including [sub‑I/research/leadership role], with [consistent/strong] evaluations and no further interruptions. The situation is now stable, and I have full availability and readiness to begin residency on schedule.”

You’ll adjust details, but keep that skeleton.

4. How specific should you be about the family crisis?

Here’s where most people mess it up. Either they overshare or they hide behind “personal reasons” and look sketchy.

General rule:

- Name the relationship (parent, sibling, spouse, child, grandparent if you were primary caregiver)

- Name the general category (serious illness, terminal diagnosis, sudden death, major accident, psychiatric hospitalization)

- Skip detailed symptoms, hospital names, medical minutiae, or long emotional backstory

Examples of appropriate specificity:

- “My father was diagnosed with terminal metastatic cancer.”

- “My younger sibling experienced a psychiatric crisis requiring prolonged hospitalization and intensive family involvement.”

- “After my mother’s sudden death, I took time away from school to help manage legal and financial affairs for my family.”

Examples of too vague:

- “Due to personal circumstances, I had to take time away.”

- “Family issues delayed my graduation.”

Examples of too detailed:

- “My father’s small‑cell lung carcinoma had paraneoplastic SIADH that caused repeated hospitalizations…”

- “My sister attempted suicide three times over three months; I found her the first time…”

Programs are not evaluating your trauma. They’re evaluating your professional handling of a hard situation.

5. Writing it into ERAS: exact wording you can steal

Let’s get concrete. Here’s how this might look in different places.

A. ERAS “Education” or “Leave” note

If your school recorded a leave/extended time:

“Medical school extended by one year due to a time‑limited family medical crisis requiring my full‑time support. All degree requirements subsequently completed without further interruption.”

Short. Factual. Clean.

B. ERAS “Additional Information” section (primary explanation)

Use 3–6 sentences. Example:

“My medical education was extended by one year because of a significant family medical crisis. In my third year, my mother was diagnosed with an aggressive cancer, and I took a leave of absence to serve as her primary caregiver and coordinate her care. During this time, I maintained communication with my dean’s office and arranged a structured plan to complete my remaining clerkships.

When I returned to school, I completed all remaining core rotations and sub‑internships with strong, consistent evaluations and no further interruptions. The situation is now stable, and I am fully able to devote myself to residency training.”

If your delay was shorter (e.g., six months), adjust the language, but keep the same shape.

C. Personal statement (only if it truly shaped you)

If the crisis is central to why you chose your specialty or how you see patients, then fine—include a short paragraph. Do not turn your personal statement into a grief essay.

Example paragraph:

“My decision to pursue internal medicine is also shaped by my experience during my third year, when my father became critically ill. I took a brief leave from school to help coordinate his care and support my family. Watching his medical team balance evidence, uncertainty, and honest communication reinforced my interest in longitudinal, complex adult care. Returning to clinical rotations after that period, I found myself more focused on listening to patients’ goals and priorities, not just their diagnoses.”

Notice what this does:

- Connects the crisis to your professional identity

- Signals that you returned and functioned

- Does not spend 700 words on tragedy

If the crisis didn’t really shape your specialty choice, keep it out of the personal statement and let it live in Additional Info.

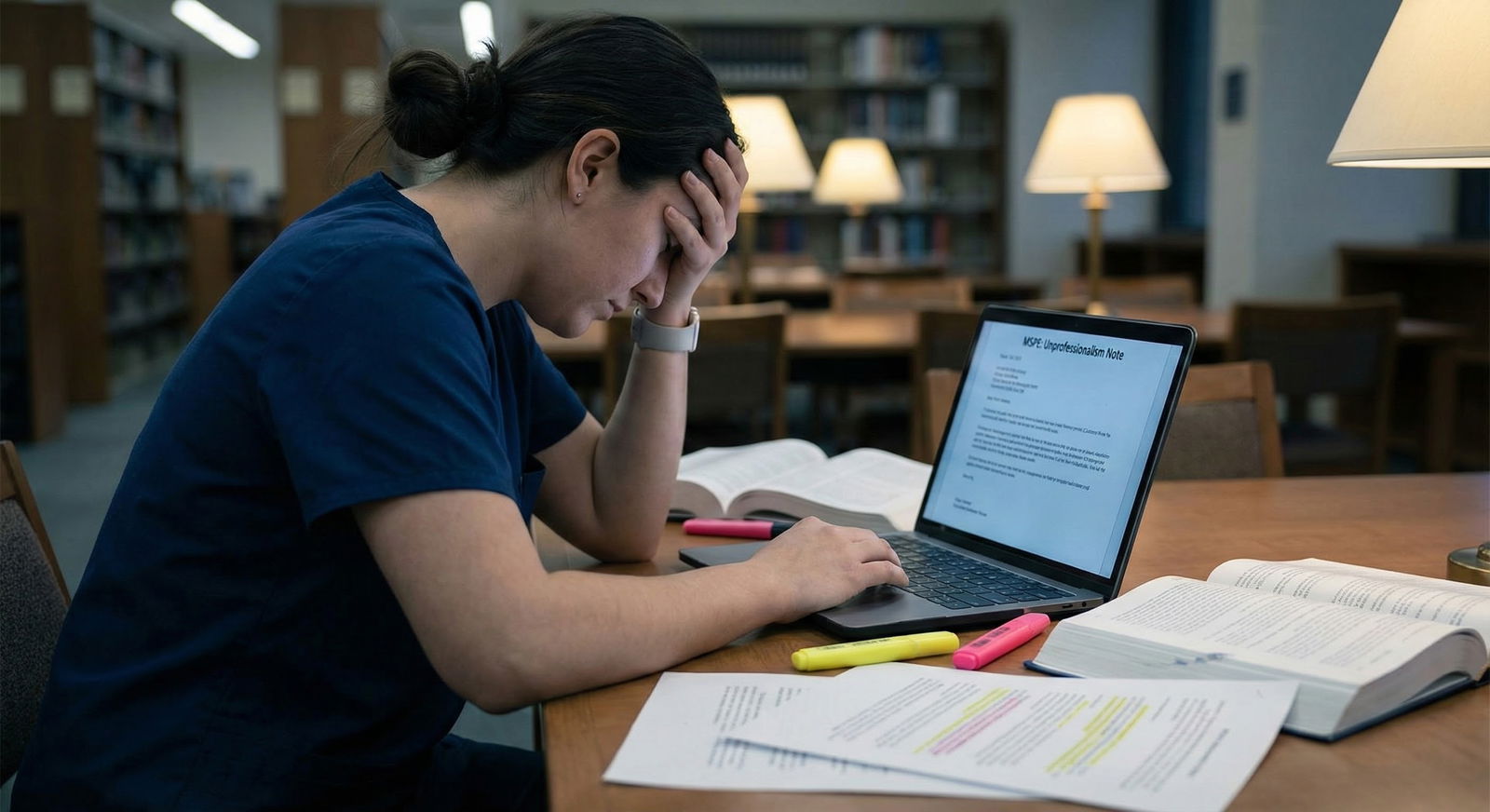

6. Align your story with your transcript and MSPE

You can write the cleanest explanation in the world, but if your MSPE says something completely different, you’re sunk.

You need to know what your dean’s letter/MSPE actually says. Request to review it early if possible.

If it says something like:

“Student took a personal leave for unspecified reasons from March 2022 to December 2022.”

You do two things:

Email your dean’s office (brief, professional) asking if they can update wording to something slightly more specific but still privacy‑respecting, e.g.,

“for a family medical crisis requiring their involvement.”

They may say no. That’s fine—you’ve at least asked.In your ERAS Additional Information, you match timeline and broaden the explanation just enough to fill in what they didn’t:

“As noted in my MSPE, I took a leave of absence from March to December 2022 due to a significant family medical crisis. I was the primary family member available to manage care and logistics, and this required my full‑time presence. After this period, I returned to complete all remaining rotations without further interruption.”

Same dates. Same general descriptions. No mismatch.

7. Handle the obvious follow-up: “Is this still going on?”

Program directors have one giant question: Is this going to interfere with my call schedule?

You must answer that—directly—even if they don’t ask.

Examples:

- “The crisis has since resolved, and my family member is now stable with appropriate support in place.”

- “My role as primary caregiver ended when my father passed away in [month, year]. I have no ongoing caregiving responsibilities that would interfere with training.”

- “Since [month, year], my family member’s care has been transitioned to local supports, and I’ve been able to focus fully on my education.”

If the situation is partially ongoing but no longer your responsibility, say that clearly:

“While my sibling continues to have chronic health needs, my role is now supportive rather than primary, and their day‑to‑day care is managed locally by other family members and healthcare providers. I do not anticipate this impacting my residency responsibilities.”

This is what PDs want: assurance that you’ve thought this through like an adult.

8. Get your letters of recommendation working for you

A good letter can convert a “red flag” into a “resilience” story.

At least one letter writer—ideally a clerkship director or sub‑I attending from after the crisis—should be able to say, in substance:

- You performed at or above the level of your peers

- You were reliable with scheduling, call, and responsibilities

- You handled stress and workload without issues

- Any gap or delay was personal/family and not academic performance

They don’t need to describe the crisis. In fact, I’d rather they didn’t. What matters is they anchor the timeline and performance post-return.

You can prompt them with language like:

“As you know, my graduation was delayed because of a family medical crisis, but I completed your rotation after returning from that leave. If you’re able, it would be very helpful if your letter could speak to my reliability and performance during that time, as programs may notice the extended training period.”

That’s not manipulative. That’s strategically honest.

9. Answering questions in interviews without spiraling

If your graduation year doesn’t match the typical four-year pattern—or your MSPE notes a leave—expect this question:

“I noticed your graduation was delayed. Can you tell me about that?”

You’re not being attacked. They just want to see if your spoken version matches what they read.

Use a tight 3‑sentence structure:

- Name & label the event

- Name your role and the consequence (delay)

- Frame your return and current stability

Example:

“During my third year, my mother developed a sudden, life‑threatening illness, and I became her primary caregiver and care coordinator. I took a [X‑month] leave, which delayed my graduation by a year, and then returned to complete the remainder of my clerkships and sub‑internships without further interruption. She’s now stable, I’m no longer in a primary caregiving role, and I feel fully ready for the demands of residency.”

Then stop talking. Do not fill the silence with more detail unless they ask.

If they probe (“That sounds difficult—how did that affect your training?”), you focus on skills gained and evidence of recovery:

“It was challenging, but it forced me to get very organized about time, priorities, and communication. When I returned, I was more deliberate about asking for feedback and staying ahead on reading. My clerkship and sub‑I evaluations since then reflect that; they’ve been consistently strong with no professionalism or reliability concerns.”

Again, you’re showing that the story ends in competence, not in chaos.

10. What if the family crisis overlapped with academic problems?

This is the harder version. Maybe your Step 1 failure or failing a rotation happened during the same time you were dealing with a parent in the ICU. Now you worry it sounds like you’re making excuses.

Here’s the line you walk: you acknowledge the problem, you acknowledge the crisis, and you show concrete changes and recovery. No “I would have done fine if not for X.”

Example for ERAS Additional Info:

“My medical education was extended in part because of a significant family medical crisis during my second and third years. During that time I failed [Step 1 / a core clerkship], which reflected both the stress I was under and my ineffective approach to studying at that time. After pausing my training to address the family situation, I worked with academic support services to develop a concrete study plan, completed a formal remediation, and subsequently passed [Step 1 / the rotation] and all remaining requirements without further issues. My later clerkship and sub‑I evaluations, as well as my [Step 2 CK] performance, better reflect my current abilities.”

The key is: the crisis is context, not your only explanation. You still show ownership and growth.

11. Timing, red flags, and how PDs actually react

Let me be blunt: a delayed graduation from a family crisis is one of the most forgivable “red flags” when handled correctly.

PDs will spend more time worrying about:

- A recent professionalism violation

- A weak Step 2 score with no upward trend

- Terrible or generic letters

- Non‑US grad with no US clinical experience

- Repeated failures with no explanation

Your job is to drop their concern level from “Hmm, what is this?” to “Okay, that’s unfortunate but fine” in about 30 seconds.

Most PDs scan for three things:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Is it ongoing? | 90 |

| Was it academic? | 75 |

| Is performance now stable? | 85 |

Not exact percentages, obviously, but you get the idea: they care about ongoing risk and current performance.

If you show:

- The crisis is resolved or contained

- Your academics and clinical work after the crisis are solid

- You talk about it like a functioning adult

Most programs will not penalize you heavily for the extra semester or year.

12. Quick do/don’t list to sanity-check your approach

Sometimes you just need a checklist.

Do:

- Use consistent dates and language across ERAS, MSPE, and interviews

- State the nature of the crisis in broad, human terms

- Emphasize your actions and your return to stable performance

- Have at least one post-crisis letter backing up your reliability

- Rehearse a 20–30 second spoken explanation

Do not:

- Hide it and hope they don’t notice the dates

- Blame your school, the healthcare system, or “drama”

- Turn your personal statement into a tragedy memoir

- Get vague to the point of sounding dishonest

- Cry in the interview while describing it (if you’re still that raw, you may need more time before residency)

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Delayed Graduation from Family Crisis |

| Step 2 | Use Additional Info with 3-part structure |

| Step 3 | Align with MSPE & Transcript |

| Step 4 | Secure Post-crisis LORs |

| Step 5 | Rehearse Interview Answer |

| Step 6 | Present as Resolved and Stable |

| Step 7 | Explain in ERAS? |

13. If you’re still in the middle of the crisis

Different situation. And trickier.

If your graduation was only partially delayed and the underlying issue is still live (e.g., chronically ill child, ongoing legal guardianship, etc.), you must be blunt with yourself about feasibility.

Ask yourself:

- Are you the only possible caregiver, or are there now others?

- Can you realistically move for residency?

- Can you handle nights/weekends/24‑hour calls without constant interruption?

If the honest answer is “I don’t know,” it may be better to delay applying one cycle, get things truly stabilized, and then apply with a clean, honest statement: “I delayed my application by one year to ensure my family situation was fully stable and would not interfere with residency.”

Program directors respect restraint and self‑awareness a lot more than magical thinking.

14. Example composite scenarios (so you can see yourself in them)

Two quick composites that mirror what I’ve actually seen work.

Scenario 1: One-year delay for parental cancer

- MS3, father diagnosed with terminal cancer

- Student becomes primary caregiver, takes 9–12 month leave

- Returns, finishes core rotations and sub‑I with solid honors/high pass mix

- Step 2 CK: strong score showing academic security

- ERAS Additional Info: clean 4–5 sentence explanation, labels “now stable,” no ongoing caregiving

- Letters: one sub‑I attending explicitly notes, “Despite an extended time in medical school due to a family crisis, [Student] was one of the most reliable and mature students on our service.”

Outcome in IM / FM / Peds / Psych:

They match. Usually without much drama.

Scenario 2: Six-month delay + failed Step 1 during sibling crisis

- MS2, sibling psychiatric hospitalization

- Student juggling exams, commuting home, mental exhaustion → fails Step 1

- Takes formal 6‑month leave to stabilize sibling’s situation and work with academic support

- Returns, passes Step 1 on second try, does solidly on clerkships, Step 2 CK in “OK but not stellar” range

- ERAS: explanation links both crisis and failure but emphasizes new study methods and stable performance since

- Letters: medicine clerkship director and sub‑I attending both emphasize reliability, preparation, no professionalism issues

Outcome in mid‑competitiveness fields:

More uphill, but with smart list construction, they still match.

Why? Because the story is: “Yes, bad thing happened. Then I changed. And here’s the proof.”

FAQ

1. Should I include documentation (death certificate, medical records, etc.) with my application?

No. Do not upload personal medical or legal documents to ERAS unless a program explicitly requests something. Your explanation plus consistent timelines plus supportive letters are enough. If a program has questions, they’ll ask. You’re applying to be a physician, not to prove your trauma in court.

2. What if my school labeled it “personal leave” and refuses to add ‘family crisis’ language?

You can still fix this on your side. In ERAS Additional Information, explicitly link your wording to theirs: “As noted in my MSPE, I took a personal leave from [month, year] to [month, year] due to a significant family medical crisis requiring my full-time involvement.” That way, they see the leave in the MSPE and the clarified reason in your own statement. PDs are used to schools being vague.

3. Is it better to be very brief (“family illness”) or give more detail?

Aim for middle ground. “Family illness” alone is too thin and sounds like a dodge. Three to five sentences that name the relationship, name the general type of crisis, explain your role, and show clear resolution—that’s the sweet spot. If you’re writing full paragraphs spilling into childhood trauma, you’ve gone too far.

4. Could a family-crisis delay push me out of competitive specialties entirely?

It depends less on the delay itself and more on the rest of your file. In very competitive fields (Derm, Ortho, ENT, Plastics, etc.), every deviation from the perfect path hurts some, but a well-handled, time-limited family crisis plus strong post-crisis performance can still keep you in the game—especially with home‑program support. If your metrics are already borderline for that specialty, the delay might be the thing that nudges you toward a more realistic choice. That’s not punishment—that’s strategic alignment of your story, your numbers, and your targets.

You cannot erase a delayed graduation from your record. You do not need to. What you can do is control the story that sits around it: clear, adult, and aligned with your current competence.

Handle that well, and the “family crisis” becomes a small, understandable chapter in your file—not the whole book. The next chapter is where you prove yourself in residency. How you write that one starts the day you hit submit on ERAS. But that’s a situation for another time.