57% of program directors say they’re “concerned” by unexplained gaps in training—yet the vast majority admit they’ve ranked applicants with gaps highly when the story made sense.

So the myth that “any gap year kills your chances” is lazy and wrong.

What actually hurts you is a badly explained gap—or a gap that clearly masks ongoing problems.

Let me walk through what the data and real-world behavior of residency programs actually show, and where applicants routinely misjudge risk.

What Program Directors Really Think About Gaps

First, let’s clear up the fantasy that programs don’t care.

They do. A lot.

NRMP Program Director Survey after Program Director Survey shows the same pattern: “Gaps in medical education or training” show up consistently on red flag lists. But they’re not treated the same way as failures, professionalism violations, or legal issues.

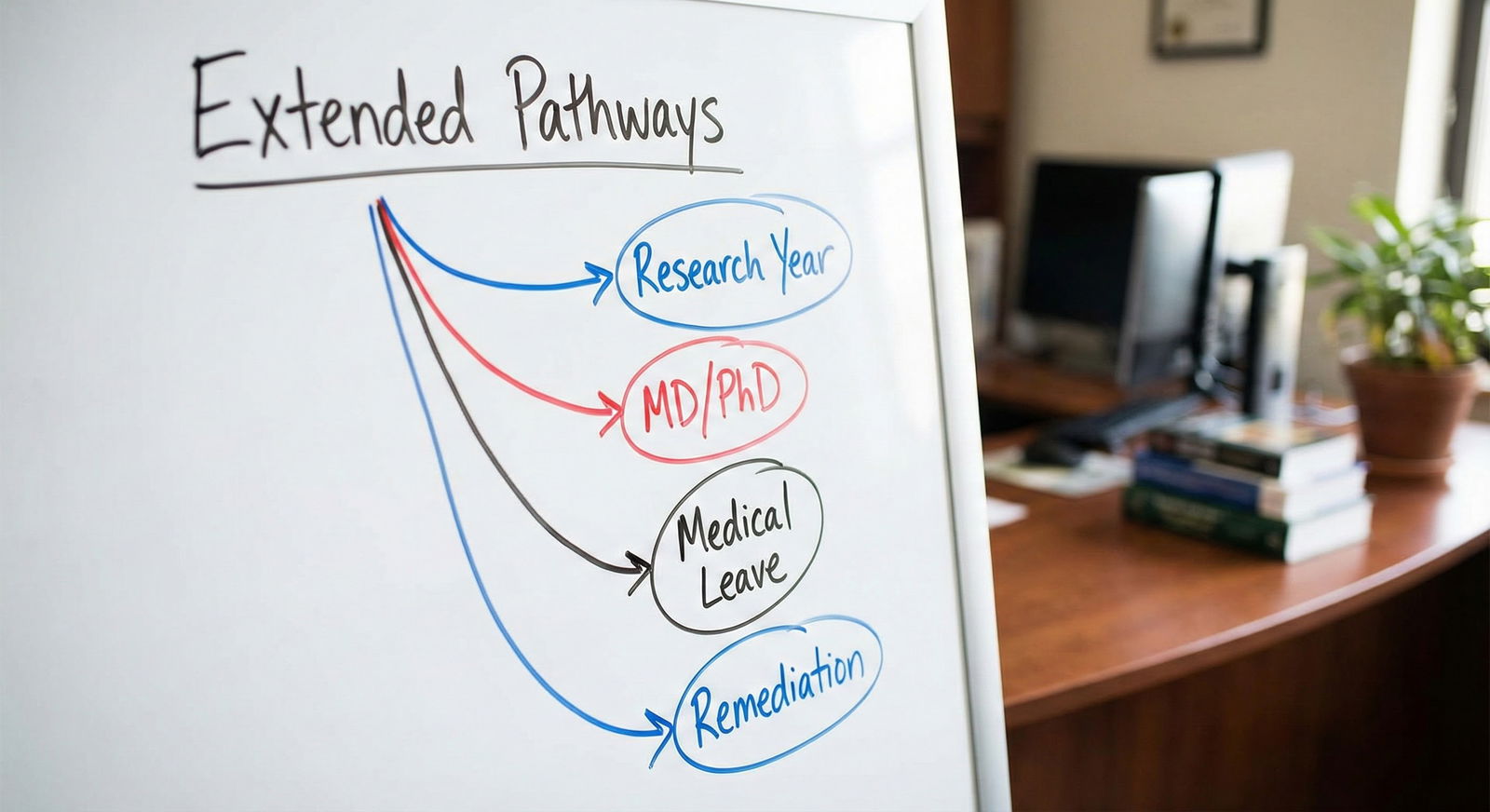

Programs basically sort gaps into three buckets in their heads:

- Normal / low-risk

- Neutral but needs explanation

- True red flag

And that sorting depends on three things far more than the mere existence of time off:

- Timing

- Duration

- Coherence with the rest of your application

If I see a one-year break between med school and residency with a clear, supported research experience and a strong Step 2 score? That’s not a red flag. That’s half your co-applicant pool in some specialties.

If I see multiple unexplained 6–12 month gaps, marginal scores, vague explanations, and weak letters? Now we’re in real red flag territory.

Let’s be specific.

Types of “Gaps” and How They’re Actually Viewed

We need to stop lumping all time away into one scary category. Programs don’t.

Here’s how different patterns usually land in a PD’s mind.

| Gap Type | Typical Risk Level |

|---|---|

| Structured research year | Low |

| Formal leave for health/family | Low–Moderate |

| Extra year for exams (single) | Moderate |

| Unmatched → reapplying (1 cycle) | Moderate |

| Multiple failed attempts / cycles | High |

| Unexplained “time off” | High |

1. Structured Research or Fellowship Year

Example: You finished MS3, took a funded research year in cardiology, published a couple of papers, then returned to finish med school.

Programs see this constantly in:

- Dermatology

- Plastics

- Ortho

- ENT

- Radiation oncology

- Some academic internal medicine tracks

This is not “suspect.” It’s practically standard in many competitive fields.

Where it does raise eyebrows is when:

- The research output is negligible (“I did a year of research” with zero posters, papers, or concrete project work)

- The story doesn’t match your specialty choice

- Your performance otherwise is mediocre (average scores, average clerkships, no clear upside)

But fundamentally, “I took a structured research year with a clear supervisor, defined goals, and tangible output” is not a red flag. It’s an asset if:

- Your work product is real enough to list concretely on ERAS

- You have at least one strong letter from that year

- You can explain succinctly how it shaped your path

2. Formal Leave of Absence for Health or Family

This is the category everyone is terrified to talk about. Mental health, serious illness, family crises.

Here’s the truth: many PDs quietly respect an applicant more when the story is clear and the recovery is convincing.

We’re talking about things like:

- Taking two semesters off after a major depressive episode, then returning, passing everything, and finishing on time otherwise

- A year off to care for a critically ill parent, documented by a formal leave, then rock-solid performance afterward

The key difference between low and high risk here isn’t why you left. It’s:

- Is the issue clearly in the past, with evidence of stability?

- Did your performance improve, stay solid, or fall apart afterward?

- Are you honest but concise, rather than evasive or melodramatic?

Most programs are not thrilled about anything that might destabilize residency call schedules. But many are far more pragmatic and humane than applicants assume. Your job is to show:

- Temporal containment (it happened then, it’s stable now)

- Insight (you learned something useful, you’re not in denial)

- Function (you’re already doing fine at full workload again)

Trying to hide a formal leave when it’s in your transcript anyway just makes you look evasive.

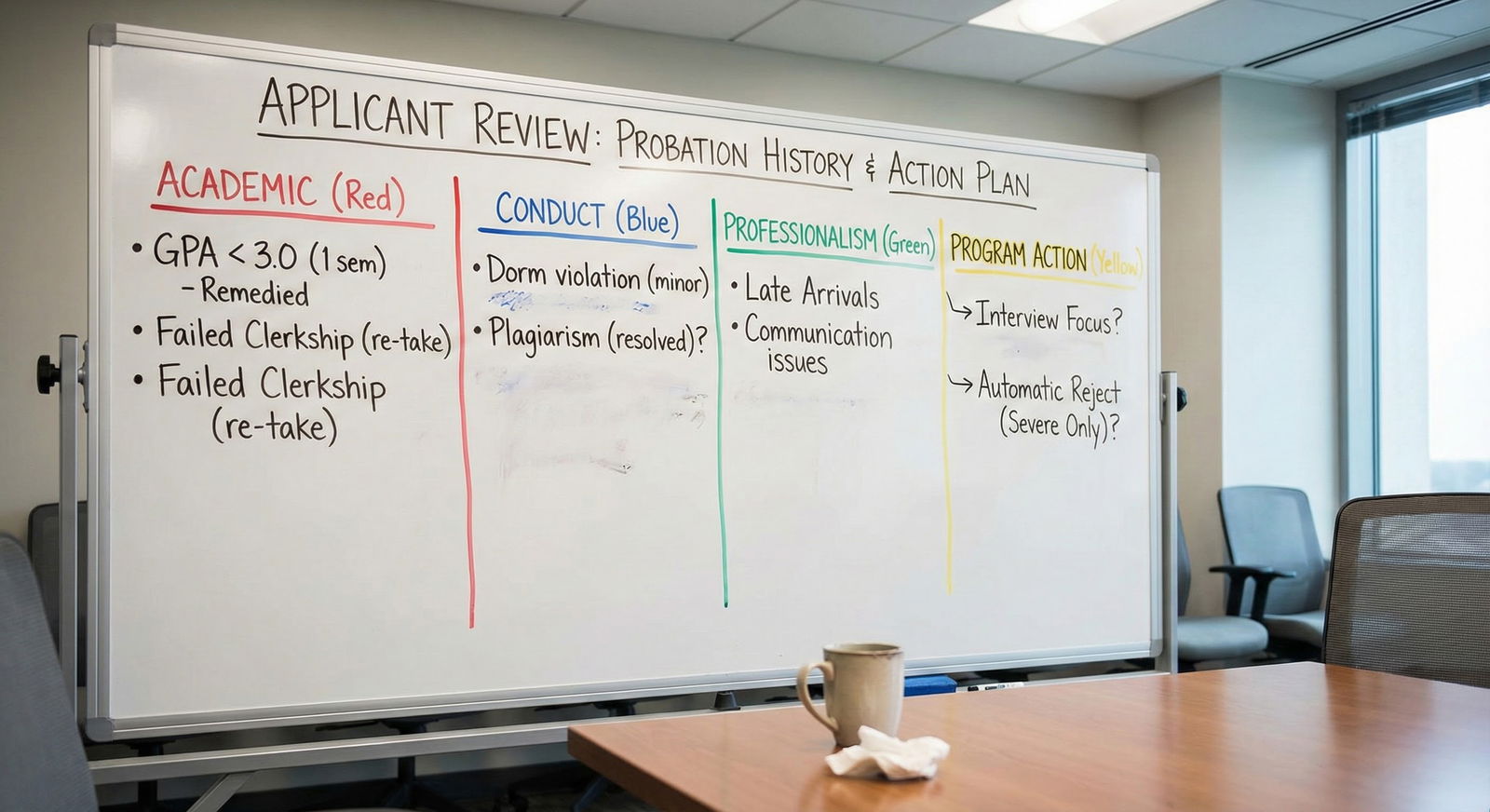

The Gaps That Actually Spook Programs

Let’s talk about what really trips alarms.

3. Exam-Driven “Gap Years” and Score Remediation

Scenario: You failed Step 1 or Step 2, took time away to study, and then came back with only a barely passing score.

This is not fatal. But it’s not neutral either.

Program directors rank these factors as major red flags over and over:

- USMLE/COMLEX failures

- Large score drops on retakes

- Multiple testing attempts

The “gap year” part here is less the problem than the pattern:

- If you took time away and then bounced back strongly—big score improvement, no further failures—that can be framed as resilience + correction.

- If you used extra time and still barely scraped by, the unspoken question is:

“What happens when we throw night float, cross-cover, and 80-hour weeks on top of this?”

So how do you mitigate?

- Be specific in what changed (study methods, support, diagnosis of ADHD, etc.)

- Show a concrete performance uptick afterwards (shelf scores, clinical evaluations, later exam success)

- Keep the explanation short and factual, not defensive

A single, explained failure with clear rebound is survivable in many fields. Multiple failures plus “quiet” gaps and no obvious upward trend? That’s where you start falling off rank lists.

4. The Unmatched Cycle and “Reapplicant Year”

Plenty of good applicants don’t match on the first try—especially in overstuffed specialties.

Where programs start drawing lines is how you used the unmatched year and whether your story indicates you actually understood the problem.

The reapplicant who did this:

- Took a structured research or prelim year

- Got new and stronger letters

- Fixed obvious weaknesses (applied more broadly, was realistic about specialty)

- Can clearly articulate what changed

…is not in the same category as the person who did the following:

- Spent a year drifting, doing vague “clinical work” that doesn’t show up as defined employment or training

- Reapplied with essentially the same application, same letter set, same flaws

- Still can’t explain why they didn’t match except blaming “the system”

Programs are absolutely capable of taking reapplicants. Many do every single year. But one question quietly determines a lot of decisions:

“Does this person look like they have insight and trajectory—or do they look stuck?”

If your reapplicant year is concrete, documented, and clearly improves your application, the year itself is not the problem. Stasis is.

Neutral Gaps That Live or Die by the Explanation

There’s a whole category of “shrug” gaps. They can be fine or they can tank you, depending entirely on how they’re framed and what else is in the file.

5. Visa / Administrative / Timing Gaps

Common with IMGs and certain dual-degree folks:

- A few months between graduation and residency because of visa processing or timing differences

- Off-cycle start due to late graduation or delayed exam results

- Extra calendar time due to formal research master’s or MPH that doesn’t neatly fit the year grid

Programs see this every cycle. It’s not some exotic anomaly.

Where people blow it is by:

- Not mentioning it at all and leaving PDs to guess

- Offering confusing timelines on ERAS that look like you’re hiding failures

- Using vague language like “personal reasons” for what was essentially paperwork

Just state it plainly:

“Four-month gap between graduation and start of research fellowship due to visa processing; during that time I continued clinical observerships at X and Y.”

Done. Not dramatic. Not suspect.

6. Short Wellness or Travel Breaks

The 2–3 month “I took a break for personal reasons/travel/family” between major phases of training? Not a big deal unless:

- It’s one of several unexplained gaps

- It coincides suspiciously with an exam failure or dismissal

- You talk about it as if it’s more important to you than medicine

I’ve seen PDs roll their eyes when applicants wax poetic about a three-month backpacking trip as if it was a transformational life experience that trumps any clinical work. Moderation matters.

Travel is fine. Lifestyle is fine. But in a file competing for a job that’s essentially controlled chaos for 3–7 years, over-emphasizing how much you cherish work–life balance can land wrong if that’s all you talk about.

A sentence or two is enough. “I took three months between graduation and my research fellowship to travel and see family before starting full-time work.” That’s it.

The Truly Suspect Gaps: Patterns, Not Isolated Years

The worst cases aren’t “gap years” at all. They’re training instability.

Here’s what sets off the biggest alarms:

- Multiple leaves of absence with fuzzy or shifting reasons

- Withdrawals or dismissals from prior training programs (med school, other residencies)

- Long stretches (year-plus) where your activities are essentially undocumented or unverifiable

- Chronic underperformance—remediation, repeated courses, repeated exams—without a clear inflection point of improvement

Program directors are not blind to context. People get sick. People have crises. People change careers.

But residency programs are under immense service pressure. They need people who will show up, learn, and not generate constant crises. When gaps look like part of an ongoing instability rather than a contained episode, the file moves to the “too risky” pile very quickly.

How to Explain a Gap Without Making It Worse

The most common mistake applicants make isn’t having a gap. It’s over-explaining, under-explaining, or obviously spinning.

Here’s the basic structure that works:

- One clear sentence of what happened

- One or two sentences of what you did with that time (productive, concrete)

- One sentence of what changed or how you’re now functioning

Let’s make that less abstract.

Example: Health leave during med school

“I took a medical leave during my third year to address a major depressive episode. During that year, I engaged in treatment, returned to part-time academic work, and gradually resumed full responsibilities. Since returning I’ve completed all remaining clerkships and electives on schedule, with strong evaluations and no further leaves.”

Not an essay. Not a confession. Just adult-level disclosure with proof of recovery.

What you don’t do:

- “For deeply personal reasons I’d prefer not to discuss…” when the transcript already flags a leave

- “I needed time for personal growth” with zero specifics

- A multi-paragraph manifesto about how the system is broken and you’re a misunderstood genius who needed space

You’re applying for a job. Answer like a professional.

What the Data Won’t Tell You (But PDs Will)

There isn’t a neat published cut-off that says “more than 9 months = doomed.” That’s not how this works.

But talk to enough PDs and a few themes keep coming up:

- Consistency > perfection

- Clear, contained setbacks > murky, ongoing issues

- Insightful, succinct explanations > defensiveness or evasion

And something else: nearly every program has at least one faculty member or prior resident who had a gap—illness, family tragedy, career switching—and came back strong. Those people often become your biggest defenders in the room if your file shows the same pattern: problem → addressed → proven recovery.

Two Myths You Can Safely Throw Out

Let me kill two persistent rumors.

“Any gap year after graduation makes you unmatchable.”

False. Extra time after graduation is definitely a bigger issue for some programs, especially in the U.S. for IMGs. But “unmatchable” is nonsense. A well-documented research fellowship, ongoing clinical work, and strong scores beat a rushed, weak application for many people.“Never disclose mental health or personal reasons.”

Also false. Vague non-answers are often worse. You don’t owe your trauma story, but a clear label plus proof of stability is far safer than pretending nothing happened when your transcript screams otherwise.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Structured research year | 75 |

| Single health-related LOA | 60 |

| Unmatched then structured year | 55 |

| Single exam-related delay | 45 |

| Multiple unexplained gaps | 15 |

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | See Gap in Training |

| Step 2 | High Concern |

| Step 3 | Low/Moderate Concern |

| Step 4 | Is it explained clearly? |

| Step 5 | Pattern of stability since? |

| Step 6 | Structured or purposeful? |

Bottom Line: When Is a Gap a Problem?

Keep these in your head:

- Time off itself is not the red flag. Unexplained, unproductive, or repeatedly unstable time off is.

- A gap that ends with clear improvement and documented performance is usually survivable—and sometimes strategically smart.

- Your explanation should be short, specific, and focused on what you did and how you’re functioning now, not on excuses or drama.

If you use a gap year to fix real weaknesses, build a coherent story, and then tell it like an adult, most programs will treat it as context—not a conviction.