Red Flags in How Programs Handle Sick Call, Coverage, and Backup Systems

It is 2:13 a.m. You are on day 9 of 12 straight, q4 call on a busy inpatient service. Your co-intern just texted: “I am in the ED getting a CT head, I think I had a syncopal episode.” You page the senior. The answer you get back is, “Ok… can you just cover their patients for the night? We’ll figure it out in the morning.”

That single moment tells you more about a program’s culture than any glossy website or “we care about wellness” slide ever will.

Let me break this down specifically: how a residency handles sick call, coverage, and backup systems is one of the purest operational markers of whether they respect residents as human beings or see you as plug‑and‑play labor. You cannot “mission statement” your way around a bad sick‑call structure.

We are going to walk through the concrete red flags, the gray-zone warning signs, and the few green flags that actually mean something. This is the stuff you need to be probing on interview day, pre-interview socials, and when you do your silent debrief in the hotel room after a long dinner with tired residents saying, “It’s fine… mostly.”

1. The Core Problem: Invisible Until It Hurts You

Programs love to talk about research, board pass rates, match lists. They almost never lead with: “Here is how we handle it when people are sick, burnt out, or hit by a bus the night before their 28‑patient ward shift.”

That silence is not random. Sick‑call systems cost real money and effort.

Well-designed systems build in:

- Redundancy (a real backup pool, not magical thinking)

- Protections against abuse (so the same 3 residents do not eat every short call)

- Psychological safety (you do not have to justify being actually ill)

- Administrative ownership (chiefs and coordinators handle logistics, not your half-delirious co-intern)

Bad systems do the opposite. They:

- Shift all the burden onto whoever is already on shift

- Guilt residents out of calling in

- Pay lip service to wellness while weaponizing “professionalism”

- Use “we are a team” as a cover for chronic understaffing

You will not see this on a slide. You have to extract it.

2. Structural Red Flags: What the System Looks Like on Paper

This is the part people skip. They think “vibes” tell them the truth. They do not. Ask explicitly: “How does sick call work here?” Then listen for specifics. If you get anything vague or hand-wavy, that is already a data point.

Here are structural red flags that should make you sit up.

A. No Dedicated Sick-Call or Backup Pool

If the answer is anything like:

- “We just figure it out as a team.”

- “The person on jeopardy usually helps, but we don’t always have one.”

- “People just cross-cover if someone is out.”

That is a structural failure.

A real program has something like:

- A dedicated jeopardy/backup resident on every major day

- A night float backup or a defined “second call” system

- Pre-specified order of escalation (backup → elective resident → shift redistribution, etc.)

If they cannot explain who exactly comes in when a ward resident, a night float, or an ICU resident calls out, they do not have a system. They have wishful thinking.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Top Academic | 80 |

| Mid-sized Community | 45 |

| Small Community | 20 |

(Think of those numbers as “% with a formal jeopardy pool.” If you are at a small community site, you need to push even harder on this question.)

B. “Self-Cover” Models

If someone says:

- “If you call out, you’re responsible for finding someone to cover.”

- “People swap among themselves when they are sick.”

Hard stop. That is a red flag.

Residents should not be cold-calling classmates while febrile to negotiate who will take their ICU shift. There must be:

- An administrator / chief resident who owns coverage

- A protocol that triggers automatically once you notify the system you are out

Self-coverage sounds “flexible” and “collegial.” In practice, it pressures residents not to call out and punishes anyone who does not have social capital.

C. Unlimited Expectations with “Informal” Rules

Example you might hear:

- “We do not have a cap on how many sick days you can take, but we ask people to be reasonable.”

Translation: there is no formal protection, and “reasonable” will be weaponized when someone actually needs time off for a serious illness, pregnancy complication, or mental health crisis.

Better answer: “You get X days per year for sick time, we track it for HR, and beyond that, serious illness or FMLA kicks in, handled via GME. We focus on making it workable, not punishing people.”

D. Backup System That Double-Books People Chronically

Some programs will say they have a backup resident, but then you find out that person is:

- On a full outpatient clinic day, “also on jeopardy just in case”

- Post-call and “technically available if needed”

- On an elective but carrying a full research or consult load

If backup is functionally a second full-time job, it is not real backup. It is uncompensated overtime pre-loaded into the schedule.

3. Cultural Red Flags: How They Talk About Illness and Coverage

On paper, any PDF can look pretty. The cultural piece is where you see who they really are.

A. Guilt and Moralizing Around Sick Call

Listen for phrases like:

- “People rarely call out; we are pretty tough here.”

- “We do not abuse sick call – our residents are very committed.”

- “Honestly, if you are not in the ICU we expect people to push through a cold.”

That is code for: “We use shame to control behavior.”

Most residents are already hyper-conscientious. If the culture adds guilt on top of that, you will have people actively working while vomiting into a trash can. I have seen this. It is not a story; it is Tuesday in some places.

A healthy culture says things like:

- “If you are sick, stay home. We would rather take the hit than have you unsafe.”

- “People do use sick call. We do not interrogate them about it.”

- “We track patterns for abuse, but that is rare; mostly we trust residents.”

B. Hero Worship of “Never Calling Out”

Watch how they tell stories.

Red flag story: “We had a senior who came in with 102 fever and still led the code blue team, what a beast.”

Green flag story: “We sent our senior home when they tried to come in sick, and backup came without a fuss.”

You are listening for what is admired. That will be the standard you are held to. If the internal hero archetype is the martyr who never calls out, your future self with influenza and 21 patients is in trouble.

C. Chiefs as Enforcers vs Advocates

Ask residents bluntly: “If you are really sick, do you feel comfortable calling chiefs? What happens next?”

Red flag answers:

- “You can call, but they sometimes push you to see if you can make it in.”

- “They will usually ask ‘how sick are you really’ and see if you can come at least for rounds.”

- “They might remind you about how hard coverage is for everyone else.”

Chiefs who act like middle managers for the hospital instead of advocates for residents are a big problem. Chiefs should be operational, yes. But their reflex in crisis should be: “Are you safe? Go home. I will figure out the coverage.”

D. Retaliation Stories

If a senior quietly tells you:

- “After X took a mental health leave, their evaluations suddenly tanked.”

- “Y was told they might not graduate on time if they ‘kept missing work’ for chemo.”

- “We had a co-resident who used sick call frequently and got labeled unprofessional.”

You do not need a bigger red flag. That is a program willing to punish vulnerability. It will not magically be kind to you when it is your turn.

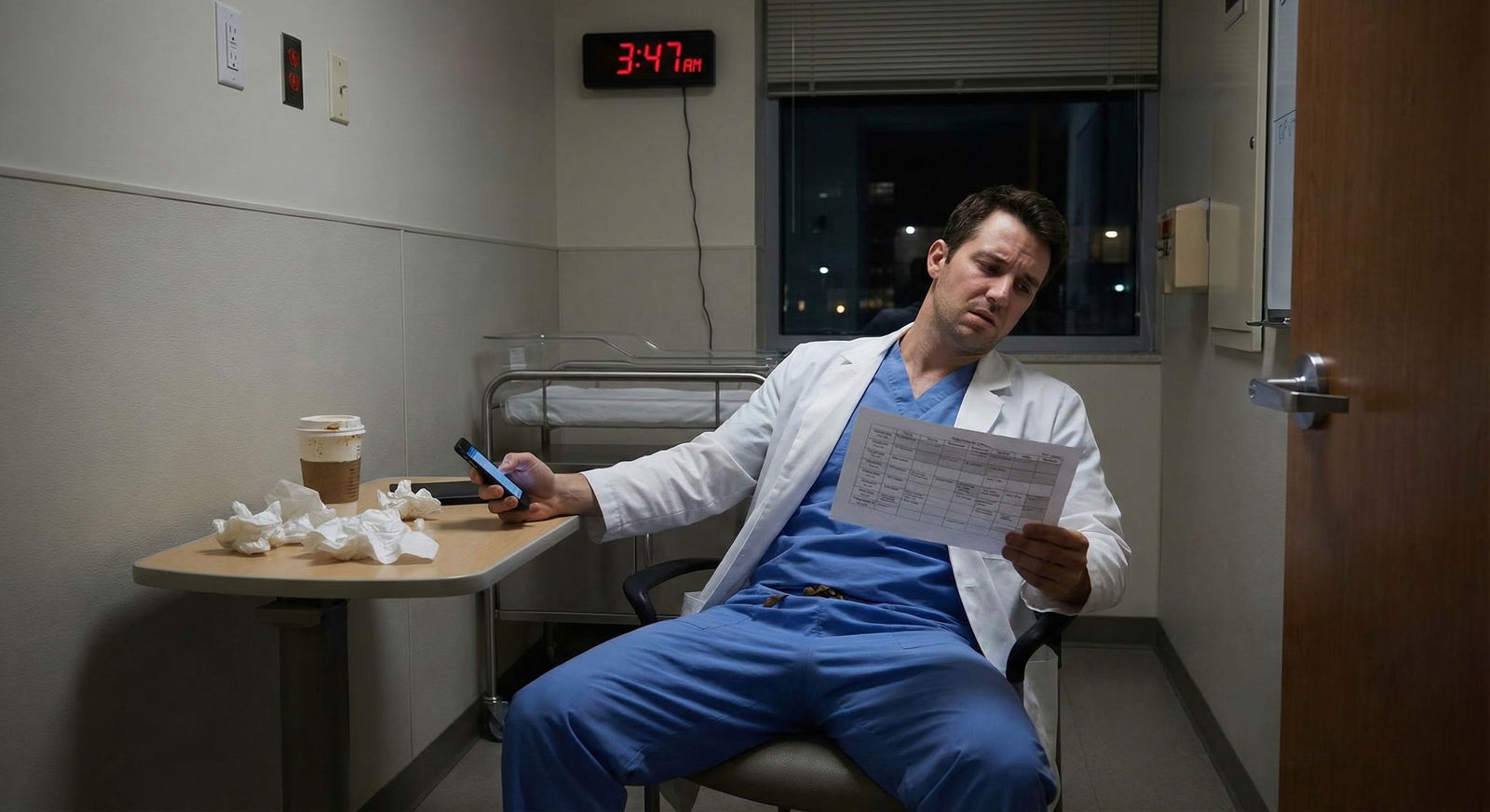

4. Operational Red Flags: What Actually Happens at 3 a.m.

Now, the practical side. Structures and culture both feed into operations: what happens in real time when the house of cards wobbles.

A. Coverage = Unsafe Workloads

Ask: “When someone calls out on wards, how many patients might each remaining resident carry?”

If the answer includes:

- “We all just pick up a few extra; census can be around 20+ sometimes.”

- “There is no cap when we are short, we just do what we have to do.”

- “ICU can go up to 15 each if we are really short.”

That is not a coverage system. That is a safety hazard. For you and for patients.

Look for programs that:

- Have hard caps (and actually respect them)

- Have a defined “disaster mode” plan that triggers backup, not just “try harder”

- Admit when something is unsafe and modify admissions or redistribute work

| Service Type | Normal Cap per Resident | Short-Staff Day Cap (Still Safe) |

|---|---|---|

| General Medicine | 10–14 | 14–16 |

| Step-down / SDU | 8–10 | 10–12 |

| MICU/SICU | 8–10 | 10–12 |

| Night Float (Med) | 8–12 admissions | 12–14 (with help) |

If you are hearing “20+” and “we just make it work,” that is chronic over-extension disguised as grit.

B. No Night Backup, Ever

Night is where programs expose their true priorities. Ask:

- “If night float is sick, what happens?”

Good answer: “We have a dedicated night jeopardy resident. They come in. If two people are down, chiefs and fellows scramble, and we immediately call in extra attending support.”

Bad answer: “The day team stays late or comes back; we try not to let that happen often.”

Translation: “We have built no redundancy into nights. You will work 24+ hours but we will not call it that.”

C. Clerical and Nursing Work Gets Dumped on “The Extra”

Another subtle operational red flag: what happens to the person who is backup and actually comes in.

Healthy approach: “Backup is treated like a full resident. They get the patients of the sick colleague, and the system recognizes this as work: they get post-call time, schedule adjustments, or a lighter stretch afterward.”

Toxic variant:

- Backup arrives and is used as a glorified phlebotomist / transport assistant because there is no central nursing or ancillary flexibility.

- They get no schedule compensation. It is “just part of the job.”

- Their presence becomes an excuse for everyone else to offload low-value tasks instead of addressing system problems.

Backup should be for preserving safety and workload, not as a band-aid for every system failure in the hospital.

5. Interaction with Leave, Pregnancy, and Mental Health

Sick call exists on a spectrum with larger leave issues: maternity, paternity, medical leave, mental health stays, injuries.

If a program botches those, their day-to-day sick-call culture is almost surely bad.

A. Pregnancy and Parental Leave Red Flags

Look for:

- Residents whispering about who “got away with” how much leave

- Stories of co-residents covering huge chunks of someone’s maternity leave with no structural plan

- Hand-wavy answers about how graduation is affected by extended leave

Better programs:

- Have a standard parental leave policy that is explained clearly

- Build parental leave into manpower planning, not as an afterthought

- Do not treat pregnant residents as schedule problems to be “worked around”

If the answer to “How was it for your last pregnant resident?” starts with a sigh or eye roll, you have your answer.

B. Mental Health and “Call Outs”

Ask this question directly at the social, not to the PD: “Do people feel comfortable taking time for mental health, therapy, partial leaves if needed?”

Listen for these red flags:

- “You can… but people worry about it getting back to leadership.”

- “You have to be careful what you say is the reason.”

- “We usually just say it is a ‘medical’ reason and leave it vague, it is safer.”

If residents feel they must lie to access care, that program is not psychologically safe. Full stop.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Very comfortable | 15 |

| Somewhat comfortable | 40 |

| Not comfortable | 45 |

6. Interview Tactics: Specific Questions That Expose Red Flags

Enough theory. Here is how you actually smoke this out on interview day and socials.

Ask Residents (Not Faculty):

- “Walk me through the last time someone called out sick on wards. What exactly happened, step by step?”

- “What happens if you wake up with vomiting at 3 a.m. on a night float week?”

- “Is there anyone people are afraid to call when they are sick?”

- “Do people actually use sick call, or is there an unspoken expectation not to?”

- “How many times in the last year did someone come in who clearly should have stayed home?”

You are looking for facial expressions, not just words. The half-second pause, the smirk, the “honestly…” preface. That is the truth.

Ask Faculty / PDs:

- “How is your sick-call and backup system structured? Who coordinates it?”

- “How do you monitor for and prevent resident burnout or presenteeism?”

- “What changes have you made to your backup/sick call in the last 3 years?”

If they cannot answer #3 with anything meaningful, they are probably not iterating. And that is a problem, given how obvious this issue has become nationally.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Resident feels too ill to work |

| Step 2 | Notifies chief via phone or system |

| Step 3 | Chief confirms resident will stay home |

| Step 4 | Backup resident activated |

| Step 5 | Escalate to PD and attending |

| Step 6 | Coverage implemented with defined caps |

| Step 7 | Adjust admissions and redistribute safely |

| Step 8 | Schedule adjusted later to compensate backup |

| Step 9 | Backup available? |

Compare that to what you often hear in real life: “We just text the group chat and hope someone responds.”

7. Subtle Warning Signs That Add Up

Not every red flag is a giant siren. Some are smaller tells that, when combined, tell you to rank a program lower.

A. “We Don’t Really Use Sick Call Much”

On its face, that could mean they are well-staffed and people are healthy. More often it means:

- Culture strongly discourages calling out

- Residents are proud of “never missing a day”

- Underlying burnout is high but unspoken

Ask a follow-up: “Is that because people rarely get sick, or because there is pressure not to call out?”

If you get a laugh and “yeah, we just push through,” don’t kid yourself.

B. Backup Mostly Used for Non-Clinical Stuff

If the main examples residents give of backup use are:

- Coverage for retreats

- Helping with random admin projects

- Proctoring exams

That suggests the system might be built more for the program’s convenience than resident safety.

C. Confusion Among Residents About the Policy

If you ask 3 different residents, “How many sick days do you get?” and get 3 different answers, it means:

- Communication is poor

- There is likely a gap between written policy and lived experience

You should not need to be a third-year chief to understand how you can call out.

8. Green Flags (Because They Do Exist)

Since this is an article on red flags, I will keep this short. But some programs genuinely get this right.

Green flags you should actively seek:

- Transparent, written sick-call policy given at orientation and available online

- Dedicated jeopardy/backup positions with protected time (not double-booked)

- Chiefs who tell you flat out: “Call us if you are sick. We will figure it out. We do not interrogate you.”

- Residents sharing stories of being supported in serious illness, pregnancy, or mental health crises without career punishment

- Recent changes that show they are reacting to resident feedback (“We added a second night backup after a near miss last year”)

If you hear these consistently from multiple residents, you are looking at a program that at least takes the issue seriously.

| Category | Strong sick-call system | Weak sick-call system |

|---|---|---|

| PGY1 | 65 | 75 |

| PGY2 | 55 | 80 |

| PGY3 | 50 | 85 |

9. How Much Weight Should You Give This When Ranking?

More than most applicants do.

Programs will tout prestige, fellowship outcomes, research. They will not spotlight the week you are alone with 28 patients because your co-intern has COVID and backup is “busy in clinic.”

Here is my view, bluntly:

- A program that mishandles sick call will reliably harm you 5–20 times a year.

- A program with fewer research opportunities might mildly inconvenience your CV once or twice.

- You can create research projects. You cannot single-handedly create a safe backup system at 2 a.m.

So when you are doing your silent ranking calculus:

A slightly less “fancy” program with a well-run coverage system and humane sick-call culture beats the shiny name that glorifies working through pneumonia. Every time.

FAQ (Exactly 6 Questions)

1. How directly can I ask about sick call without sounding “high maintenance”?

Be direct and neutral. “Can you walk me through how sick call and backup coverage work here, for both day and night shifts?” is completely appropriate. Programs that interpret that as high maintenance are telling you who they are.

2. Is it a red flag if residents say they almost never use sick call?

It depends on the tone and context. If they pair it with, “But people feel comfortable using it when needed, and I’ve seen it work well,” that is less concerning. If it is said with pride about toughness, or followed by stories of people coming in sick, that is a red flag.

3. What if a program does not have a formal jeopardy or backup resident?

Then you need a very clear answer on what happens when someone is out. Some small programs rely on flexible census caps and attending help. That can be ok if residents describe it as safe and sustainable. If the plan is “everyone just works more,” that is a problem.

4. How many sick days is “normal” for residency?

There is no magic number, but most residents will have at least a few days per year where they should not be at work. Any culture where people claim they and everyone else have literally zero sick days year after year is either lying or suppressing illness.

5. Can a bad sick-call system be fixed while I am there, or is it usually static?

Programs can and do fix this, but it requires leadership that actually listens to residents and is willing to spend FTEs on backup. If senior residents say, “We have been complaining about this for years and nothing changes,” do not expect a sudden conversion while you are there.

6. Should I ever call out if the system is clearly abusive and will punish me?

Yes, if you are truly unsafe to work—for your sake and for patients. Document objectively (symptoms, urgent care notes, etc.) and communicate professionally. An abusive system may still retaliate, but that is a system problem, not a professionalism problem. Long-term, prioritize programs where you do not have to choose between your health and your reputation.

Three core points to take with you:

- How a program handles sick call, coverage, and backup is one of the clearest windows into its true culture and safety.

- Vague answers, self-coverage expectations, guilt around calling out, and unsafe census spikes are not minor issues; they are structural red flags.

- Rank higher the places where residents can describe, in concrete terms, a system that let them be sick humans without being punished or endangering patients.