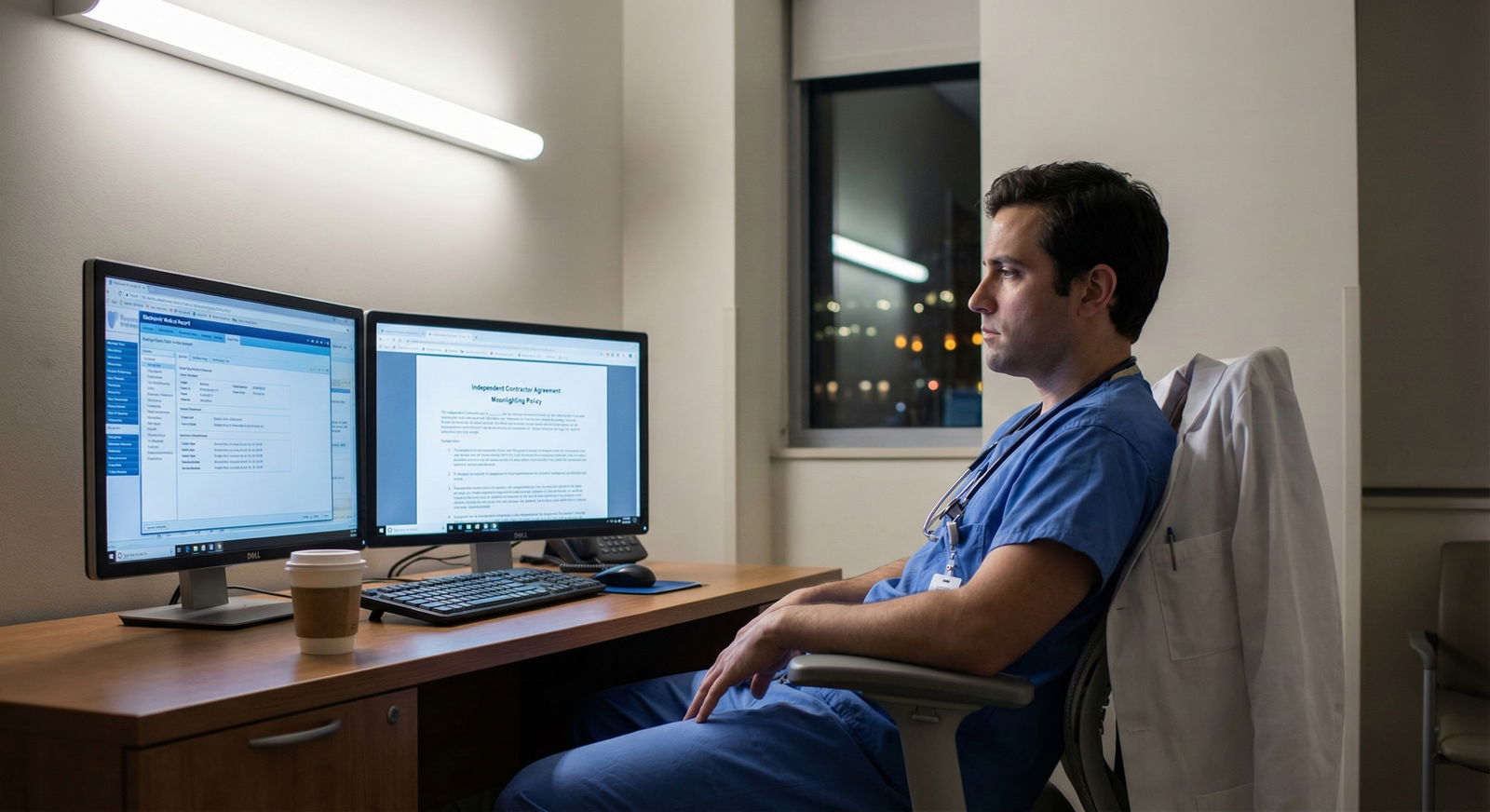

Most residents do not miss red flags in personalities. They miss red flags in the EMR.

Let me be blunt: if you are not reading between the lines of how a program talks about documentation, “EMR efficiency,” and “workflow support,” you are walking straight into some of the scut‑heaviest roles in the hospital.

Everyone knows to avoid “malignant culture” and “80‑hour weeks.” Fewer people recognize that the way a program structures notes, orders, documentation burden, and who actually touches the EMR is one of the clearest windows into whether your life will be education‑focused or clerical‑focused.

I am going to walk you through exactly which documentation patterns, pre‑rounding norms, note expectations, and “EMR optimization” tricks scream hidden scut. This is the stuff residents complain about at 2 a.m. at the workstation when they forget they are being overheard.

1. The Core Idea: EMR Workflows As Truth Serum

Scut does not announce itself as “We’ll make you do pointless work.” It hides in:

- “We prioritize thorough documentation.”

- “Residents own the medical record.”

- “We are leaders in EMR innovation.”

- “We have strong relationships with our nursing and ancillary staff.”

All of those phrases can be completely fine. Or they can mean: your day will be primarily note‑writing, form‑filling, and inbox‑clearing while someone else does the interesting parts of care.

Here is the principle:

Whoever holds the keyboard holds the scut.

If the EMR is configured so that:

- Residents enter all orders

- Residents generate all documentation for billing

- Residents handle most discharge paperwork and messaging

- Residents reconcile meds, complete “care coordination” forms, and click all the quality boxes

…then you are the throughput engine for the hospital, not a trainee with protected time to think.

2. How Programs Talk About Notes: Phrases You Should Translate

You will not see “We expect 10 detailed notes per day” on a website. You will see euphemisms.

Let me translate a few common ones.

“Residents own the chart”

This can be healthy: residents synthesize, attendings co‑sign, clear ownership of assessment and plan.

But sometimes “own the chart” means:

- You write every single daily note

- You do all the med recs

- You complete every “required” template for quality and billing

- Attendings essentially edit your work for billing credit

- “On a typical ward day, how many notes do you personally sign?”

- “Does anyone else write or start notes—NPs, scribes, attendings?”

- “Who does med recs and discharge summaries on weekends?”

If the answer is “Residents do all of it, every day, even on 16‑patient caps,” you have your first big scut flag.

“We emphasize comprehensive documentation for billing and quality”

Translation: the hospital’s RVU and quality metrics are embedded directly into your note templates.

Warning signs:

- Daily notes with huge auto‑populated sections that must be manually “touched” to count

- Required “core measure” checkboxes buried in every progress note

- Metrics tracked at the resident level (“You missed the CHF education field on 3 patients last week”)

When I hear, “We’ve worked closely with compliance to optimize our templates,” I ask, “Optimized for whom? Learners or billing?”

“Our notes are standardized to ensure continuity”

“Standardized” can be great. But if residents describe:

- Multi‑page templates that must be completed fully even for short‑stay, low‑acuity patients

- Rigid text macros where attendings insist on specific wording for billing levels

- Requirements that every problem be restated with full history daily

…you are staring at a note‑factory culture.

Ask: “Are interns evaluated on note length or clinical reasoning?” You would be surprised how often the hidden answer is “length.”

3. Pre‑Rounding & Data Gathering: The Silent Scut Engine

The pre‑rounding pattern tells you who the program actually believes should be interacting with patients versus screens.

| Pattern | Likely Culture Signal |

|---|---|

| 30–45 min pre-rounding | Data + patient interaction |

| 1–1.5 hr pure chart pre-round | EMR-first, checklist mentality |

| Interns arrive 1–2 hrs earlier | Hierarchy-based scut distribution |

| Shared pre-round (team split) | Efficient, team-based workflow |

Red flag patterns in pre‑rounding

- Interns come in dramatically earlier than seniors “to pre‑round”

If interns arrive at 4:30–5:00 a.m. to:

- Comb through labs

- Scroll vitals trends

- Open every nursing note

- Pre‑populate templates

…and then seniors stroll in at 6:30 to “review the overnight events,” the program has decided whose time is for scut and whose time is for thinking and teaching. That will not change when you become a senior; you will just inherit a new flavor of scut.

- Pre‑rounding means computer first, patients second

Healthy: glance at overnight data, see the patient, document succinctly.

Scut‑heavy:

- “You should know every lab and vital trend for 5 days back before you walk into the room.”

- “We expect detailed written pre‑round notes before attending rounds begin.”

- Residents describe: “I saw my last patient 3 minutes before we started rounds because I spent forever in the EMR.”

Ask this directly: “During pre‑rounding, do you see patients before or after you document?” If multiple residents say “after,” that is not a minor detail. That is a cultural choice.

- Seniors or attendings expect written pre‑round notes separate from daily notes

Sometimes called:

- “Pre‑round summaries”

- “Morning check‑in notes”

- “Preliminary progress note before rounds”

So you write:

- Early‑morning “pre‑round” note

- Full progress note later

- Discharge summary for anyone leaving

- Admission H&P for new overnight patients

No one calls that what it is: double documentation. You call it what it is: scut.

4. Order Entry, Messaging, and “Task Ownership”

Orders and messaging are where a lot of modern scut has migrated. Old‑school scut was fetching films. New‑school scut is inboxes, order sets, and endless “quick tasks.”

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Direct patient care | 20 |

| Documentation | 35 |

| Order entry & messaging | 25 |

| Education/teaching | 10 |

| Other tasks | 10 |

Who enters orders?

In a scut‑light culture:

- Residents enter most orders, but:

- Nurses can place certain protocol orders

- Pharmacists adjust meds within agreed protocols

- APPs share order entry on their patients

- There is smart use of order sets and favorites

In a scut‑heavy culture:

- Every single medication change, imaging order, nursing order, diet order, and “miscellaneous” thing flows through the resident.

- Entire teams stall because “the resident has not yet put the order in.”

- Residents are interrupted constantly during rounds with “Can you put in X now?”

Ask: “How many non‑urgent pages or chats per day are just order requests?” When residents say, “Honestly half my afternoon is just ‘please order Tylenol’ messages,” that is your signal.

Inbox management and “in‑basket” work

Outpatient especially can be brutal here.

Watch for:

- “Residents help manage the clinic in‑basket between visits.”

- “We learn longitudinal care by responding to patient messages and refill requests.”

- A “team‑based inbox” that in practice gets dumped on whoever is physically present

This is not inherently bad. But if there are no:

- Clear caps

- Protected times

- Explicit attending ownership

…it becomes infinite, unbounded scut. A classic line you will hear: “Oh, and we usually clear a couple dozen patient messages at lunch.” That is not benign.

5. Templates, Macros, and “EMR Optimization” That Actually Signals Scut

Everyone claims to be “EMR‑savvy.” The question is whether the EMR is optimized for clinical reasoning or for box checking.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Pre round data review |

| Step 2 | Pre round note |

| Step 3 | See patient |

| Step 4 | Update full progress note |

| Step 5 | Place orders |

| Step 6 | Discharge summary |

| Step 7 | Inbox messages |

| Step 8 | Evening signout note |

If that diagram looks like your future, pay attention.

Note templates that balloon with autopopulated fluff

Red flags:

- Templates that automatically pull in: full lab panels, radiology results, medication lists, problem lists, “smart phrases” for every chronic disease

- Attendings or coders scold residents for deleting unnecessary autopopulated sections

What this means in practice:

- Notes are 3–5 single‑spaced pages that no one reads.

- Residents spend more time managing the note than thinking about the patient.

- Billing and quality projects are being run through your keyboard.

Ask residents: “Are you allowed to keep your notes short if your assessment is clear?” If they laugh, you have your answer.

Mandatory “checklists” embedded in notes

Quality and safety teams love this trick: embed a checklist into a note template so “it can never be missed.”

Examples:

- Daily VTE prophylaxis check

- Indwelling catheter checklist

- Central line checklist

- Dietary/SSI counseling for diabetics

- Heart failure discharge instructions

Good in theory. Abusive in practice when:

- Residents are expected to manually scroll through and click these on every note for every patient, even when unchanged.

- They are audited and shamed if a box is missed.

You want automation and team‑based responsibility, not “resident as walking quality form.”

6. Who Does The Truly Awful Paperwork? Discharges, Transfers, Prior Auth

There is a hierarchy of paperwork misery. Some tasks are inherently resident‑level; some are just lazy delegation.

Discharge summaries

Reasonable:

- Resident writes discharge summary for patients whose care they actually managed.

- Templates are sane; med rec can be reconciled directly in the EMR.

- On weekends, there is some triage: short‑stay or straightforward cases may use abbreviated templates.

Scut‑heavy:

- Residents write discharge summaries for patients they have never seen, based purely on chart review.

- Discharge summary requirements include paragraphs of manually retyped information (e.g., code status, problem lists) that the EMR could auto‑pull.

- Administration audits discharge summaries for “narrative quality metrics” and pushes feedback down to residents only.

Ask residents: “On a call shift, what is the worst part of post‑call morning?” If the first answer is “chasing and writing 10 discharge summaries,” not “sign‑out,” you know the structural problem.

Transfers and interfacility forms

Programs that protect residents:

- Have case managers or transfer coordinators handle most of the form‑filling.

- Use standardized electronic forms that pull data from the chart.

- Limit resident role to clinical justification and key medical details.

Programs that treat residents as clerical staff:

- Expect residents to fill out multi‑page transfer packets manually.

- Require residents to call multiple accepting facilities, fax records, and track down signatures.

- Make “failed transfers” or incomplete paperwork a resident problem, not a system problem.

Listen for this phrase: “We rely on residents to really make sure the transfer happens.” That is code.

Prior authorizations and disability paperwork

In outpatient heavy specialties (IM, FM, psych, PM&R), this is a big differentiator.

Red flags:

- “Residents help with prior auths to learn systems of care.”

- “We all pitch in on disability and FMLA paperwork; it is part of longitudinal care.”

Ask: “Do you have centralized staff to handle prior auth and disability forms, or is that done by residents/attendings?” You want: “We have staff that handle the bulk, residents only rarely get involved for complex cases.”

7. Role of APPs, Scribes, and Support Staff: Does It Lighten Or Add Scut?

APPs, scribes, and coordinators can be either your salvation or your competition. It depends entirely on how the program uses them.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| No APPs/Scribes | 100 |

| APPs Only | 75 |

| Scribes Only | 70 |

| APPs + Scribes | 50 |

APP teams that absorb scut vs APP teams that take all autonomy

Optimal:

- APPs share patient load; they do their own documentation and orders.

- Residents still write their own notes on teaching patients and lead management.

- APPs and residents divide tedious tasks sensibly (e.g., one handles discharges, the other admissions) with clear expectations.

Dysfunctional:

- APPs manage the interesting, stable rounding lists and secure continuity.

- Residents bounce between admit‑heavy teams and are used for note‑spamming and cross‑cover.

- Residents say sentences like, “The NPs have their own patients; we mostly handle all the new admits, codes, and random tasks.”

Scribes:

- If a program has scribes on teaching services and uses them correctly, your note burden should drop, not just shift.

- Red flag: “We have scribes… but only on private/attending‑run services, not on resident teaching services.”

Care coordinators:

- Good programs: coordinators handle SNF paperwork, home health forms, transportation arrangements, and a chunk of communication with outside facilities.

- Bad programs: “The resident needs to fill everything out and then the coordinator will help send it.”

8. Specific Questions To Ask Residents That Expose Hidden Scut

You will not get these answers from PDs. You must ask current residents, ideally one‑on‑one or in small groups without leadership present.

Ask about a normal ward day

“Walk me through a typical day on wards. What time do you get in, and what are the main things that actually take up your time?”

Listen for:

- Time spent solely in EMR vs with patients or team

- Number of notes per day

- Comments like “The afternoon is mostly cleaning up documentation”

Ask about worst days

“What are the objectively worst days on this rotation? What makes them bad?”

If the answer is mostly:

- “Terrible admits, really sick patients, lots of codes”

that is hard but educational. If the answer is:

- “Six discharges with endless discharge summaries and home health forms”

- “Clinic days with 20 patients plus a massive in‑basket”

you are hearing systemic documentation overload.

Ask how performance is evaluated

“On what aspects of documentation do you get feedback or ‘reminders’?”

If they mention:

- Late notes

- Missing specific billing elements

- Missed quality fields

more than they mention reasoning, communication, or clarity, that is a red flag.

9. The “Future of Medicine” Angle: Where This Is Actually Going

Programs will tell you they are “preparing you for the future of value‑based care.” Sometimes true. Sometimes an excuse to weaponize EMR features against resident time.

| Period | Event |

|---|---|

| 2005 | Paper charts, mixed responsibility |

| 2010 | Early EMR, resident-heavy order entry |

| 2015 | Quality checklists embedded in notes |

| 2020 | In-basket explosion and protocol orders |

| 2025 | AI-assisted notes but metric tracking expands |

Realistic trends:

- EMRs will continue to accumulate quality and regulatory requirements.

- Automation (AI note drafting, predictive orders) will help only if programs deliberately use it to protect resident time rather than raise expectations.

- Documentation will not get simpler unless someone fights for it. That someone is not usually GME leadership; it is you and your resident colleagues pushing back.

Here is the hard truth: Some programs like having residents as cheap, flexibly scheduled, intelligent clerical workers. They will happily route every new documentation requirement through you. Label it “training.”

You want a program that is already asking:

“How do we keep residents focused on learning and clinical decisions while the system evolves?”

Not:

“How do we use residents to keep up with evolving documentation demands?”

10. Concrete Indicators A Program Is Relatively Scut‑Light On EMR

Just so this does not sound entirely nihilistic, let me spell out what good looks like. During interviews or second looks, look for these:

- Residents say: “Our notes are actually pretty short. Attendings prefer concise.”

- Pre‑rounding is 30–60 minutes, with clear expectation to see patients, not just EMR‑surf.

- There are scribes or MA support in busy clinics, and residents actually get them.

- APPs and coordinators handle a meaningful chunk of discharge and transfer logistics.

- In‑basket work is structured with clear time blocks and attending oversight, not an endless background noise.

- Residents roll their eyes at the occasional stupid checklist, but it is occasional, not omnipresent.

If you hear: “Documentation is a thing, but it does not dominate our day,” that is actually rare. And valuable.

FAQs

1. Is heavy documentation always a red flag, or is it just part of residency?

Heavy documentation by itself is not the issue. The red flag is when documentation is:

- Disproportionate to patient complexity

- Clearly driven by billing or quality metrics rather than patient care

- Duplicative (pre‑round note + full note + discharge summary for the same short stay)

- Unequally distributed to residents when others could safely share the load

Every resident will write notes. The question is whether the EMR work feels like learning and synthesis, or like unpaid clerical labor.

2. How do I differentiate between “owning the chart” in a good way vs being exploited?

Owning the chart in a good way means:

- You write the assessment and plan because you are directing care.

- Your notes are read and discussed during rounds.

- You have autonomy to structure your documentation as long as it is safe and clear.

Being exploited looks like:

- Being forced into rigid templates primarily for billing.

- Writing extensive notes that attendings copy‑edit for their own billing without meaningful feedback.

- Spending most of your workday on documentation instead of interacting with patients or learning.

3. What if current residents seem resigned and say, “This is just how medicine is now”?

You are hearing normalization of dysfunction. Physicians who trained on paper charts will tell you: no, it does not have to be this way. There are programs that fight back—by streamlining templates, hiring support staff, pushing back on pointless metrics, and shielding residents from the worst of it. If everyone talks like the EMR is an immutable law of nature, not a design choice, that is a cultural red flag.

4. Are outpatient clinics always worse for scut and EMR work?

Not always, but they are higher risk. Outpatient brings:

- High visit volume

- Massive in‑basket message flow

- Refills, prior auths, disability paperwork

- Use nurses, MAs, and centralized staff to handle a big chunk of this.

- Give residents realistic patient caps and controlled inbox expectations.

Bad ones simply bolt residents onto an already overwhelmed clinic and tell themselves they are “providing continuity experience.”

5. Can I tell from a program’s website or interview presentation that it will be scut‑heavy?

Rarely from official materials. Everyone says they are “efficient,” “innovative with EMR,” and “committed to resident wellness.” You detect the truth via:

- Off‑script resident comments (“Afternoons are mostly finishing discharges and notes”)

- Specific answers when you ask about pre‑rounding, note expectations, and in‑basket policies

- How residents talk about weekends and post‑call days

The more concrete the answers (“We average 8–10 notes per day on wards, and discharges are usually the bottleneck”), the easier it is to spot problems.

6. What specific EMR questions should I ask on interview day without sounding negative?

Use curiosity, not accusation. For example:

- “How has your program changed EMR workflows in the last few years to reduce resident burden?”

- “On a typical ward day, about how much time would you say residents spend in the EMR versus with patients?”

- “Do residents ever get scribes or other documentation support on busy services?”

- “Who usually handles discharge paperwork and med recs—residents, APPs, or coordinators?”

The way people react to these questions—whether they give specific, thoughtful answers or dismiss them—tells you almost as much as the content.

If you remember nothing else:

- The EMR is not neutral. How a program uses it is one of the clearest, least‑advertised red flags for hidden scut.

- Ask residents for concrete details: notes per day, pre‑rounding norms, in‑basket expectations, and who actually does discharges and paperwork.

- Choose programs that fight documentation creep on your behalf, not ones that quietly route every new requirement through your keyboard and call it “training.”