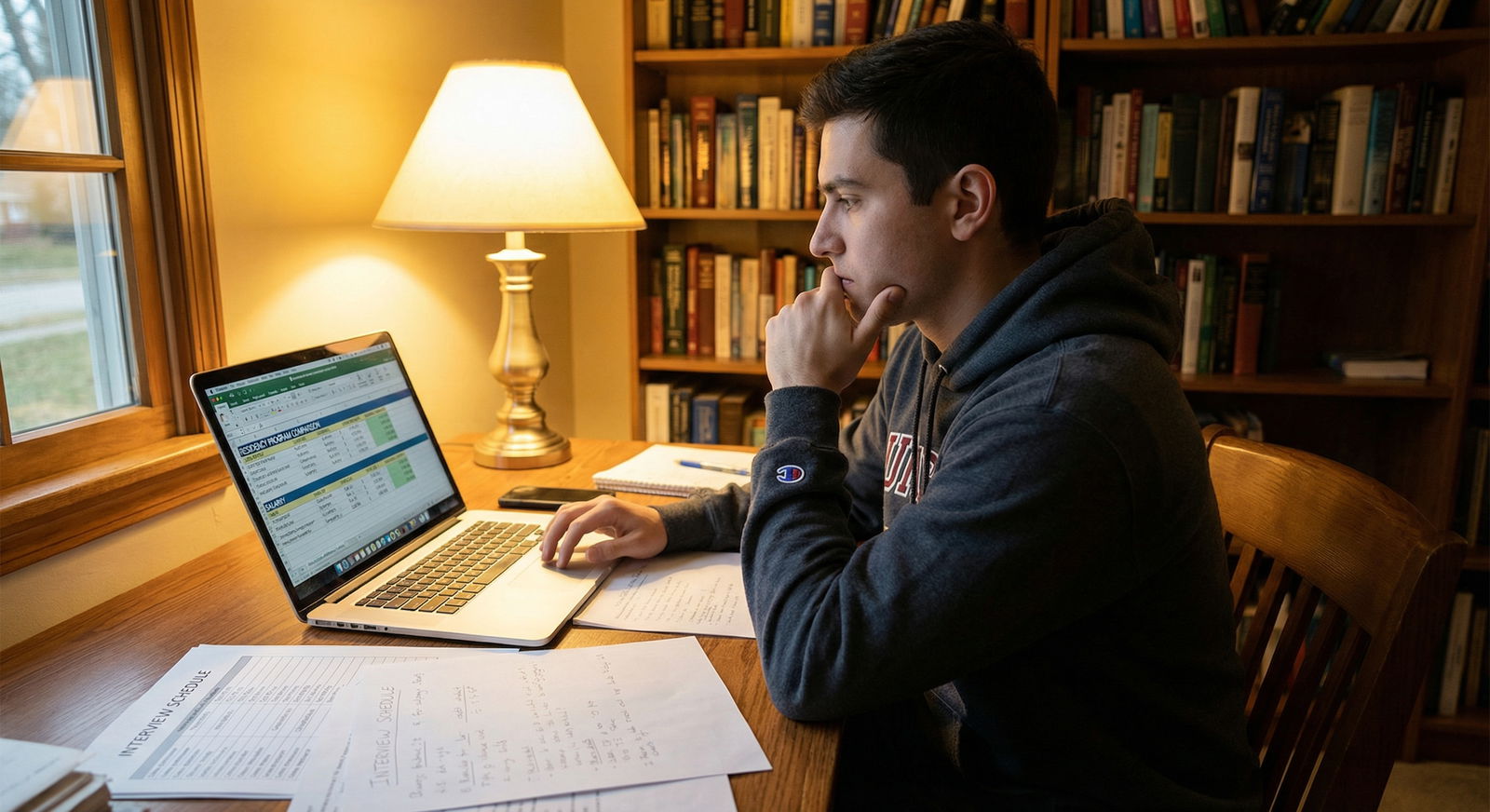

Only 38% of current U.S. faculty trained at what applicants would label a “top research” residency program.

Let that sink in. The majority of people with academic titles—Assistant/Associate/Full Professor—did not come from the handful of NIH-top-10 or name-brand powerhouses you keep seeing on Reddit rank lists.

The idea that “if I don’t match into a heavy research program, I’m locked out of academics” is one of the most persistent, self-sabotaging myths in residency choice. It’s also just wrong. Not “partially nuanced” or “it depends” wrong. Factually wrong for most specialties and most trainees.

You are not choosing between “academic career” and “community servitude” on Match Day. You’re choosing an environment that will either make it easier or harder to build a track record. Those are not the same thing.

Let’s dismantle the myth properly.

What the Data Actually Shows About Where Academic Faculty Come From

The obsession with “top research programs” is built on a lazy assumption: that academic faculty disproportionately come from a tiny list of brand-name residencies. When you actually look, the picture’s very different.

](https://cdn.residencyadvisor.com/images/articles_svg/chart-estimated-distribution-of-u-s-academic-faculty-by--2974.svg)

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| High-Research Flagship (NIH Top 20) | 38 |

| Mid-Research University | 34 |

| [Community or Hybrid Programs](https://residencyadvisor.com/resources/choosing-residency-program/community-vs-academic-debunking-stereotypes-about-career-options) | 28 |

No, this is not a randomized RCT, but multiple specialty-specific snapshots all tell the same story:

- Look at medicine, pediatrics, EM, psych: faculty rosters are full of people from state schools and mid-sized university hospitals you never see on “top 10” lists.

- Surgical fields skew more academic-heavy at the top, but even there, plenty of chairs and division chiefs trained at unsexy programs and built careers later.

Walk through any academic department webpage at a mid-tier med school and count how many faculty did not do residency there. You’ll find people from “no-name” programs you’ve barely heard of. I’ve sat in promotion meetings where the chair couldn’t remember where someone did residency—but knew their h-index, recent grants, and teaching awards cold.

Residency prestige is a weak predictor once you control for what actually matters: publications, fellowships, niche expertise, and people who will actually pick up the phone for you.

There are exceptions—ultra-competitive basic science-heavy careers, MD/PhD pipelines, certain surgical subspecialties where pedigree still buys you more. But the blanket statement “research-poor programs can’t get you academic positions” just doesn’t survive contact with reality.

What Actually Gets You an Academic Job (Hint: It’s Not Just Your Program’s NIH Ranking)

Programs don’t hold academic jobs in escrow for their graduates. People hire:

- Productivity (papers, projects, QI, curricula)

- Demonstrated skills (teaching, clinical niche, leadership)

- Connections and reputation

You can get all of that at a non-research-heavy program—if you’re strategic.

Think about what hiring committees actually see:

Your CV

Number and quality of publications. First-/second-author vs token middle. Mix of clinical research, QI, education, etc. If you show up with 5–10 decent papers from a mid-tier or “research-poor” program, you’re more interesting than someone from Big Name University with one weak case report.Your letters

Two brutally strong letters from people who actually know you and can say, “I worked with this person for 3 years; they drive projects forward, teach well, and I would hire them again,” beats a tepid letter written by a famous name who barely remembers you.Your fellowship and niche

Many academic clinicians are hired because of fellowship training or a clinical niche: transplant ID, cardio-onc, ultrasound, med-ed, simulation, informatics. You can get into good fellowships from many places as long as your application is strong.Your track record of showing up

Committees care whether you finish what you start. If you repeatedly start projects and vanish, nobody will hire you no matter how shiny your home institution is.

Program research output helps because it gives you more scaffolding: ongoing trials, existing databases, structured mentorship. But if that scaffolding is dysfunctional—no time protected, mentors checked out—it’s not an asset. I’ve watched residents at “top” places produce basically nothing while a motivated person at a medium program quietly churned out posters, clinical series, and curriculum projects, then walked into a faculty job.

The Real Difference Between “Research-Rich” and “Research-Poor” Programs

The big myth is binary thinking: either a place is “research-rich” and you’re set, or “research-poor” and you’re doomed.

Reality is a spectrum with three questions that actually matter:

- Can you get access to some mentor who publishes?

- Will you have enough time and schedule flexibility to work on projects?

- Does the program culture support residents doing more than just surviving?

A small community program with a single faculty member quietly publishing in their niche and a PD who gives you elective time to work with them can be more productive for you than a huge NIH powerhouse where nobody has time to answer your email.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Active Mentor Access | 90 |

| Protected Time or Schedule Flexibility | 75 |

| Culture Supporting Projects | 70 |

| Program NIH Rank | 30 |

In practice, the stuff that actually matters:

Mentor density vs accessibility

Ten famous researchers who don’t respond to emails are worse than one mid-level faculty member who loves involving residents.Schedule structure

Do seniors get electives with real flexibility? Are research electives possible or just theoretically “on paper”? Is every golden weekend getting eaten by cross-cover?Administrative friction

Can you get IRB approval without a year-long slog? Is there someone (a research coordinator, librarian, QI office) who helps with logistics?PD attitude

I’ve heard PDs openly say, “We’re a workhorse shop; if you want to do tons of research, go somewhere else.” That’s your cue. Others at small programs will literally help rearrange rotations so you can finish a paper.

Labeling a program “research-poor” often reflects website optics and NIH dollars, not your actual ability to generate output as a resident.

How People From “Non-Researchy” Programs End Up in Academia

Let me lay out the pattern I’ve seen repeatedly. It’s boringly consistent.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Match at mid or community program |

| Step 2 | Find 1 engaged mentor |

| Step 3 | Complete 2 to 4 projects |

| Step 4 | Present at regional or national meetings |

| Step 5 | Apply to solid fellowship or junior faculty |

| Step 6 | Continue projects in niche |

| Step 7 | Academic appointment |

Common playbook:

- Intern year: you find the one person who likes working with residents on projects. You show up, on time, do the grunt work.

- PGY2–3: you crank out a retrospective series, a QI project, maybe a curriculum paper. You go to a couple conferences. You get comfortable with abstracts and submissions.

- Fellowship (if applicable): now you leverage that track record. Bigger projects, better mentors, more funding.

- Early faculty: you are hired at a mid-tier or even big-name place because you’ve shown (not promised, shown) you can produce.

I’ve watched:

- A resident from a small Midwestern community IM program get into a strong academic cardiology fellowship, publish solid clinical work, and return as faculty at a major city academic center.

- An EM resident at a so-called “community” shop build an ultrasound education niche, get fellowship, and land at a big-name university as ultrasound faculty.

- A psych resident at a mid-tier state hospital do basic med-ed projects, join a major coastal academic department, and now run a residency curriculum.

The through-line: they made research capacity for themselves. The fact their home program didn’t have a massive NIH portfolio slowed them down slightly; it didn’t wall them off.

When You Actually Should Worry About a Program’s Research Depth

Now, let’s be clear. There are situations where lack of local research infrastructure is a real problem—not just Reddit anxiety:

You want a heavy research career (grants, PI, tenure-track)

If your goal is R01-level bench or translational work, it’s delusional to pretend a tiny community program with zero basic scientists will serve you well. You need early scaffolding, labs, methodologists, statisticians. Here, going to a research-rich place matters a lot.Hyper-competitive academic tracks in certain surgical or subspecialty fields

In some areas (e.g., neurosurg, CT surgery, certain onc subspecialties), the competition for prestigious fellowships and faculty tracks still rewards pedigree plus big-name mentors. You can still make it from a smaller program, but the uphill slope is steeper.Programs with truly zero culture or capacity for scholarly work

There are residencies where faculty literally don’t do any projects, have no idea how to run an IRB, and no one has published in years. If the PD shrugs when you ask about research, that’s a red flag if academia is a serious priority for you.

But that’s not the same as: “Anything below Top 20 equals career death.”

The smart question is not “Is this program research-poor?” but “Does this program give me enough tools to build a respectable early track record if I’m willing to do the work?”

How to Evaluate a “Research-Poor” Program Like a Grown-Up

You’re not shopping for a brand label; you’re shopping for a functional environment. So ask targeted questions, not “Do you value research?” fluff.

| Area | Concrete Question |

|---|---|

| Mentorship | “Can you name 2–3 faculty who regularly publish with residents?” |

| Output | “How many resident first-author papers or major abstracts were there last year?” |

| Time | “How are residents given time to work on projects? Any research elective that actually happens?” |

| Support | “Is there a research coordinator or QI office that helps residents?” |

| Trajectory | “In the last 5 years, how many grads took academic or fellowship positions?” |

Notice those are all verifiable. No hand-wavy “we encourage scholarship” nonsense.

On interview day and during second looks, pay attention to:

- Whether residents can name a mentor who helped them actually finish a project

- If posters on the wall have resident names or are all from attendings

- How they talk about electives—are they survival breaks or spaces to build something?

If a place is “research-poor” on paper but hits several of those boxes in practice, you can absolutely build an academic trajectory there.

A More Honest Way to Use “Research” When Ranking Programs

Instead of lumping programs into “academic” vs “community” and assuming only the former lead to faculty jobs, try a more adult framework.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Clinical Training Quality | 35 |

| Program Culture and Support | 30 |

| Research and Scholarly Opportunities | 20 |

| Geography and Personal Life | 15 |

Here’s how I’d actually think about it if you care about future academics:

- First: ensure clinical training is strong. Weak clinical training kneecaps any future academic credibility.

- Second: make sure the culture doesn’t crush you. Burned-out residents do not publish.

- Third: verify minimal viable research infrastructure—some mentors, some history of resident projects, at least the possibility of electives or flexible blocks.

- Fourth: consider geography and personal realities. Being near a partner, support system, or a city that doesn’t make you miserable is not trivial; miserable people do not do scholarship.

Then, between two otherwise similar programs, a more research-robust place can tilt the scales. But you’re choosing margin, not destiny.

And if you happen to match at a place that’s a little lighter on research? Stop catastrophizing. Start emailing.

The Bottom Line on “Research-Poor” Programs and Academic Careers

Three things to walk away with:

- Academic faculty come from everywhere, not just top research powerhouses. Your residency brand is a footnote once you show real productivity.

- What matters is not whether a program is “research-poor” on paper, but whether it offers enough mentorship, time, and support for a motivated resident to produce work.

- For most people aiming at a clinical academic job, a mid-level or even “community” program won’t block you. Your habits, mentors, and follow-through will.

The myth that only research-rich residencies lead to academic positions is comforting in a way. It lets applicants blame Match outcomes instead of their own choices and effort. Reality is messier—and more empowering. You have more control than that.