The data show a simple truth: early research experience does not just decorate a CV – it measurably shifts the odds of where you match for fellowship and what kind of academic career you can build.

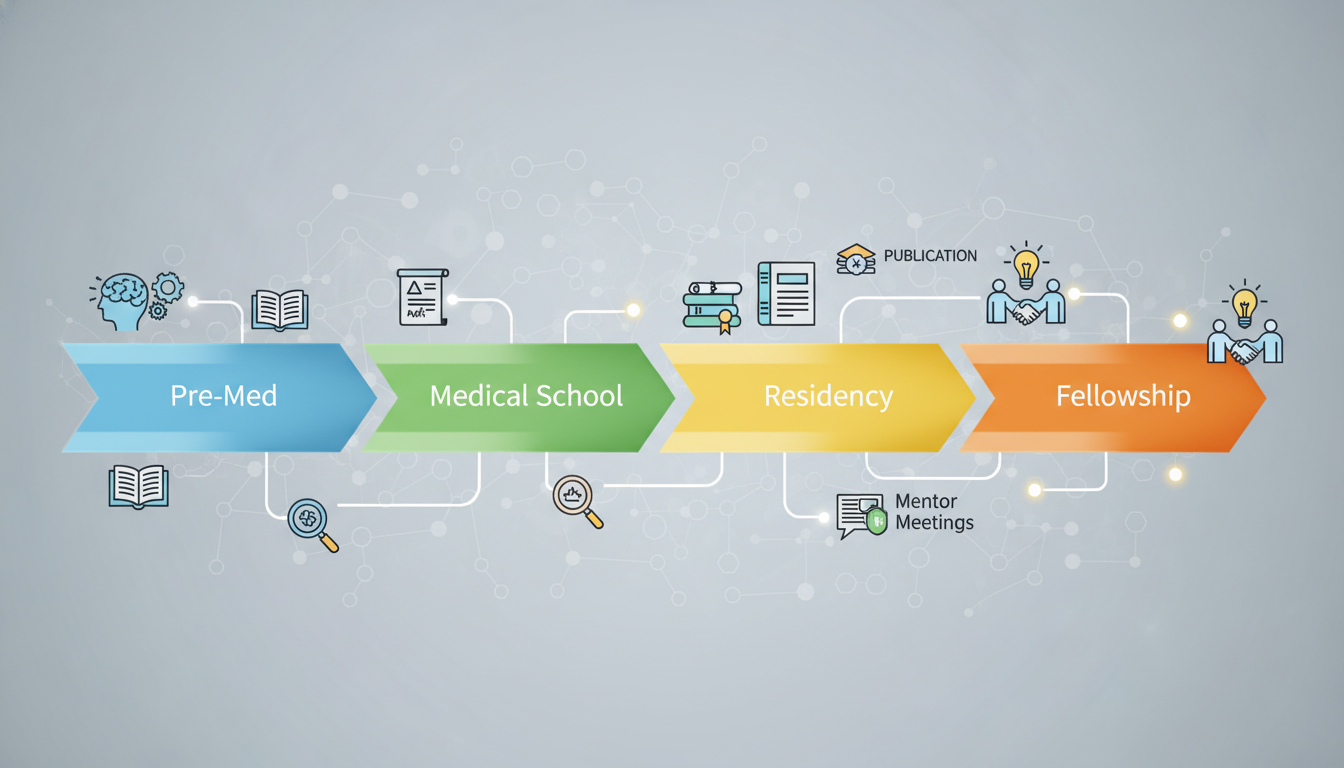

Most applicants treat research like a checkbox. The numbers suggest it functions more like compound interest. Small, early investments grow disproportionately over 8–10 years of training: from premed, to medical school, to residency, and finally to fellowship.

This is a longitudinal story, not a one-cycle story.

(See also: Funding vs Unfunded Projects for insights on research funding.)

Below is a data-driven look at how early research affects fellowship placement, and what premeds and medical students can do now to change their statistical trajectory.

(Related: What PIs Really Look For When Choosing Pre‑Med Researchers)

1. The Pipeline Reality: Research and Competitive Fellowships

Before going granular, it helps to look at the top of the funnel: who actually ends up in competitive fellowships.

Several studies and national datasets show consistent patterns:

- In top-tier academic fellowships (e.g., cardiology, GI, heme/onc, dermatology, radiation oncology), between 65–90% of fellows had substantial research output during medical school or early residency.

- Among residents who secure research-heavy academic fellowships at top 20 research institutions, published data often show median 5–10 publications by the time of fellowship application, with a significant fraction beginning during medical school.

A few concrete data points:

- USMLE/NRMP Program Director Surveys repeatedly show research productivity as a top 5 factor for fellowship-selection specialties. For heme/onc, cardiology, and GI, program directors rank “evidence of scholarly activity” at or near the level of standardized test scores and letters of recommendation.

- A study of internal medicine residents applying to cardiology fellowship at a single large academic center reported:

- Matched applicants: median 5 publications, 2 first-author

- Non-matched applicants: median 2 publications, 0 first-author

Many of those 5 publications originated from medical school projects.

The pattern is consistent: the further along you go into competitive subspecialty training, the higher the probability that successful applicants have deep research histories that started early.

Early research is not just correlated with fellowship placement; it often precedes and predicts it.

2. How Early Is “Early”? Premed vs Medical School

“Early research” covers several distinct timepoints, and the longitudinal effect differs by phase.

2.1 Premed Research: A Leading Indicator, Not a Requirement

For fellowship placement, premed research is a leading indicator rather than a strict prerequisite.

The limited data we have show:

- In MD-PhD and research-track pipelines, >80% of matriculants report substantial premed research, often ≥1 year and sometimes multiple posters or publications.

- In standard MD cohorts at research-intensive schools, somewhere between 35–55% of students report at least one formal premed research experience.

How does that connect to fellowship?

Analyses from several research-heavy medical schools show similar patterns:

- Students with premed research + continued research in medical school were significantly more likely to:

- Enter research-oriented residencies

- Pursue academic careers

- Match into competitive subspecialties

One institution’s internal review of graduates (N≈700 over multiple years) showed:

- Among graduates who ultimately matched into “high-intensity research fellowships” (e.g., physician-scientist tracks in oncology, cardiology, or transplant ID), ~70% had documented premed research.

- Among those matching into primarily clinical, non-academic fellowships or no fellowship, premed research exposure was closer to 30–35%.

This does not mean you must start in college, but the data suggest that:

- Students who do research early are more likely to self-select into research-intensive paths later.

- Faculty are more likely to invest in students who already know basic research workflows (IRB, data collection, etc.).

Premed research is a directional signal that compounds later.

2.2 Medical School Research: The Pivot Point

Medical school is where the numbers start to sharpen.

Across multiple specialties, the competitive fellowships draw disproportionately from:

- MD-PhD graduates

- MD graduates with dedicated research years (e.g., NIH, HHMI, year-out programs)

- MDs with ≥3–5 peer-reviewed publications by graduation

Consider a few specialty-linked trends (compiled from institutional and published data):

- Dermatology (residency, then procedural and complex medical fellowships):

- Matched applicants often report 8–12 publications on ERAS; a substantial fraction originates from medical school, and many go on to fellowships in complex medical dermatology, dermatopathology, or procedural derm.

- Radiation Oncology:

- Matched residents frequently have 10+ publications total by end of residency; many matched fellows in academic programs started publishing during medical school.

- Internal Medicine → Heme/Onc or GI:

- Fellows at top 20 research institutions often show 3–6 med school publications, then another 3–6 during residency.

The pattern: starting research only in residency compresses the timeline. You can still get there, but the density of work required per year is higher. Early medical school research spreads that output over more years and reduces the need for extreme catch-up later.

3. Quantity vs Quality: What the Data Show About Output Metrics

Program directors rarely say “we only care about quantity,” but outcomes data show they pay attention to count, role, and relevance.

3.1 Publication Count and Match Probability

A systematic review of residency outcomes, while focused on residency rather than fellowship, offers useful quantitative signals:

- Applicants with ≥3 publications had higher odds of matching into competitive specialties than those with zero, even after controlling for Step scores and school type.

- For fellowships, internal reviews from academic centers report similar cutpoints. For heme/onc and cardiology:

- Applicants with 0–1 publications had markedly lower match rates into top-tier academic programs.

- The steepest increase in match probability occurred as applicants moved from 0–2 to 3–5 total publications.

For many fellowships, the “credibility threshold” seems to cluster around 3–5 total publications by application time, with higher numbers beneficial in highly academic environments.

3.2 First-Author vs Middle-Author

Not all lines on a CV function equally.

Several cardiology and oncology fellowship program directors have explicitly noted:

- First-author original research carries disproportionate weight compared to:

- Middle-author multicenter trials

- Non-peer reviewed abstracts

- Case reports

One cardiology fellowship’s internal scoring rubric (published in a program review) assigned:

- 3 points for each first-author original article

- 1 point for each middle-author article

- 0.5 points for case reports or letters

- With a cap, but a clear emphasis on being primary driver of a project

Among matched applicants in that program, median research score was significantly higher than in non-matched interviewees, even with similar test scores, underscoring that leadership in research (not just presence) correlates with success.

3.3 Specialty Alignment

Data also point to field-specific work mattering more than generic research.

For example:

- Internal medicine residents applying for GI who had GI/hepatology–focused publications had higher match rates into GI fellowships than peers with equal total publication counts in unrelated fields (e.g., cardiology, nephrology).

- A similar pattern appears in oncology: heme/onc fellowship applicants with cancer-specific research (even case series and retrospective chart reviews) were favored compared with those whose work was entirely outside the oncology domain.

This creates a clear optimization strategy: starting research early in the field you may ultimately want increases your chances of getting both residency and then a matching fellowship with a coherent scholarly narrative.

4. Timing: When Research Happens Matters

Research is not only about “how much” but also “when.” The timing of output influences how decision-makers weight it.

4.1 Premed and Early Medical School

Premed research is mainly useful for:

- Gaining basic skills (data cleaning, basic statistics, IRB, literature review)

- Signaling long-term interest in scholarly work

- Occasionally producing early publications (but many do not publish before medical school)

Early M1/M2 research serves a similar foundation-building function. It is when you learn:

- How to structure a project

- How long manuscripts actually take to publish (often 12–24 months)

- How to collaborate with faculty and residents

Quantitatively, early projects tend to mature just in time for residency applications. A project started in M1:

- Data collection during M1–M2

- Analysis M2–early M3

- Manuscript submission M3

- Publication in M4 or early PGY1

Applications often include “submitted” or “in-press” work that originated years earlier. Without early start, that timeline shifts uncomfortably into residency.

4.2 Dedicated Research Time and Year-Out Programs

The strongest data signal for high-end academic fellowship placement comes from those who took dedicated research years:

- HHMI, NIH Medical Research Scholars, institutional research fellowships, or dual-degree (MD-PhD, MD-MPH with research focus)

- MD-PhD graduates have markedly elevated rates of entering academic fellowships and obtaining K awards later. One longitudinal study reported:

- >70% of MD-PhD graduates entered careers with substantial research content, many via academic subspecialty fellowships.

- Students who took a dedicated research year during medical school reported:

- Higher mean number of publications (often 5–8 vs 1–3 for non-research-year peers)

- Higher subsequent match rates into academic fellowships in specialties like heme/onc, GI, cardiology, and pulmonary/critical care.

The data signal is strong: a concentrated year in med school multiplies your scholarly output and sets you up for an academic narrative that fellowship programs recognize.

4.3 Residency-Only Research: Compressed but Possible

For those who start research in residency, the numbers show a tighter but not impossible window:

- Internal medicine: 3 years of residency, with fellowship applications going out in PGY2. That leaves roughly 12–18 months of real research time before you must have something substantial for your application.

- Realistically, projects that start PGY1 and move efficiently can yield:

- 1–3 abstracts/posters

- 1–2 publications by fellowship application, especially if retrospective or secondary analyses

Residents who started research in medical school enter residency often already having multiple published or in-review works. Their residency years then add on, instead of starting from zero.

Program-level reviews show that residents who matched into top academic fellowships had, on average, double the number of publications of their co-residents who did not, and more of that work was initiated before residency began.

5. Mechanisms: Why Early Research Translates into Fellowship Advantage

The relationship is not mystical. Several measurable mechanisms connect early research to eventual fellowship placement.

5.1 Network Effects

Starting research early gives you:

- More time to accumulate strong mentor relationships

- More opportunities to co-author with fellows and faculty who can later advocate for you

Quantitatively:

- Applicants to competitive fellowships often present 2–4 letters from research mentors.

- Those mentors frequently have reputations within subspecialties. Their names, on both letters and coauthored papers, function as trust multipliers.

Early research simply lengthens the period during which you can build and deepen those connections.

5.2 Skill Acquisition and Efficiency

Data from resident and fellow surveys show a clear pattern:

- Trainees who had prior research experience reported:

- Higher confidence with statistics, study design, and manuscript writing

- Faster project completion times

- More comfort juggling clinical demands with scholarly work

From a numbers angle, this translates into higher output per unit time.

You might not move from 1 paper per year to 5, but moving from 0 to 2–3 is often enough to clear thresholds that fellowship programs notice.

5.3 Signaling and Sorting

Research acts as a sorting mechanism:

- Students who genuinely like research stay in the pipeline, accumulating more work and moving toward academia.

- Those who dislike it may drop away from research-intensive environments over time.

By the time fellowship applications are evaluated, early research history correlates strongly with:

- Intent to keep doing research

- Probability of pursuing academia

- Fit with NIH-funded and grant-heavy divisions

Program directors know this pattern. They use early research trajectories as evidence that you are not just “doing a little project for the application” but are likely to be a long-term scholarly asset.

6. Strategy by Phase: Data-Informed Moves for Premeds and Medical Students

Viewing this through a longitudinal, data-driven lens allows more deliberate planning.

6.1 For Premeds

Data suggest that premed research is most impactful when:

- Sustained: ≥1 year of consistent involvement

- Concludes in at least one concrete product:

- Poster at a regional or national conference

- Co-authorship on a paper (even middle-author)

- Honors thesis or departmental recognition

From available surveys, premeds with 1+ substantial research products enter medical school at an advantage for:

- Securing early med school research positions

- Matching into research-oriented medical schools

- Competing for summer research programs and year-out fellowships

The gain is not only in raw output but in early “onboarding” into the research ecosystem.

6.2 For Preclinical Medical Students (M1–M2)

The data favor starting projects by early M1 or M2, especially if you are leaning toward a fellowship-heavy field.

Evidence-based objectives:

- Aim to be actively involved in at least 1–2 ongoing projects by end of M2.

- Target output by end of M3:

- 1–3 abstracts/posters

- 1+ submitted manuscript

Projects that are especially efficient:

- Retrospective chart reviews

- Database analyses using existing registries

- Outcomes research using institutional data warehouses

These have lower startup costs and shorter timelines compared to complex prospective trials or bench research.

6.3 For Clinical Medical Students (M3–M4)

By clinical years, the data suggest focusing on:

- Continuity: staying with one or two mentors and pushing existing projects across the finish line.

- Specialty alignment: shifting toward work in your likely future field, which can double count for both residency and later fellowship applications.

An M3 who:

- Has 1–2 publications (even case reports)

- Is midstream in 1–2 larger projects

is statistically positioned to finish medical school with 3–5 total scholarly outputs, a level that meaningfully improves odds in competitive residency specialties and seeds future fellowship competitiveness.

7. Field-Specific Patterns: Where Early Research Matters Most

Not all fellowship pathways weigh research equally.

7.1 High-Research Subspecialties

In fellowships such as:

- Hematology/Oncology

- Gastroenterology

- Cardiology

- Pulmonary/Critical Care

- Transplant-related fields

Program-level data show:

- Majority of matched fellows in top research programs have multiple first-author papers.

- A substantial proportion completed either:

- A research year

- An MD-PhD

- Multiple consecutive mentored projects starting in medical school

Here, early research is not just a plus. It shapes your feasibility of being considered by high-end academic divisions.

7.2 Moderately Research-Sensitive Fields

Fields like:

- Endocrinology

- Rheumatology

- Infectious Disease

place significant weight on research at major academic centers, but there is more heterogeneity.

In these specialties:

- A mix of paths (community residency to academic fellowship, etc.) exists.

- Applicants with moderate research histories (e.g., 2–4 publications, some specialty-specific) can still match well, especially if other components (letters, clinical evaluations) are strong.

Early research here still improves odds, particularly for NIH-funded programs, but the minimum statistical threshold is often lower than in heme/onc or GI.

7.3 More Clinically Focused Fellowships

Some fellowships, even within internal medicine or pediatrics, may weigh clinical performance more heavily and research modestly.

Still, across the board, national survey data demonstrate:

- “Scholarly activity” ranks as “important” or “very important” for a majority of fellowship program directors, even in more clinically oriented fields.

- Applicants with zero research are steadily less common among matched fellows at academic institutions.

The data trend: research intensity varies by field, but the directionality – more research, earlier, with continuity – almost never hurts and frequently helps.

8. Risk, Variance, and Realism

No dataset promises that “if you have X papers, you will match Y fellowship.” Outcomes are probabilistic:

- You will find applicants with 0 publications who match excellent fellowships through extraordinary clinical ability, networking, or niche program needs.

- You will also find candidates with double-digit publication counts who do not match their first-choice programs due to other factors.

However, across large samples, research behaves like a risk modifier:

- It does not guarantee success.

- It shifts the probability distribution in your favor.

Think of early research as reducing variance and increasing the expected value of your trajectory.

The longitudinal look is unambiguous: those who begin research earlier, sustain it, and progressively increase responsibility tend to cluster in the upper tail of fellowship outcomes, especially in research-heavy academic centers.

Key Takeaways

- Early research acts like compound interest: starting in premed or early medical school increases total output, deepens networks, and meaningfully improves the probability of matching into competitive, research-focused fellowships.

- The crucial thresholds are not infinite productivity but credible, aligned output: roughly 3–5+ publications (with some first-author, field-specific work) by the time of fellowship applications heavily tilt the odds in your favor.

- Timing and continuity matter: projects launched in M1–M2, sustained through residency, and aligned with your eventual subspecialty generate the strongest data-based advantage for fellowship placement.