The data shows that course load intensity matters—but not in the simplistic “take as many credits as possible” way that premed lore suggests.

Medical schools read your transcript like a time‑series dataset. They track your credits per semester, the distribution of science vs non‑science coursework, and how your GPA responds to changing load. Patterns, not anecdotes, drive how they interpret “rigor.”

Below is a data‑driven breakdown of what course load intensity signals to admissions committees, what typical accepted students actually carry, and how you can calibrate your credits per semester to maximize acceptance odds without self‑sabotage.

How Admissions Committees Actually Read Course Load Data

From an analyst’s perspective, your transcript is a longitudinal dataset with at least four key variables per term:

- Total credits

- Science credits (BCPM: biology, chemistry, physics, math)

- Term GPA

- Course level (lower‑ vs upper‑division, and lab count)

Committee members are not counting credits blindly. They infer three things:

- Capacity – Can you handle a professional‑school‑like workload?

- Consistency – Do you sustain performance under increasing load?

- Context – Are you working, doing research, or holding major leadership on top of classes?

Think of their implicit questions as:

- “Did this applicant ever sustain ≥15 credits of mostly science courses while maintaining a strong GPA?”

- “Did they increase rigor over time (more upper‑division sciences) rather than front‑loading easy terms?”

- “If they took lighter semesters, was there a clear reason in the file (full‑time work, caregiving, major leadership roles)?”

Strong applications tend to show at least 2–3 semesters that look like a “mini‑med‑school” stress test.

What the Numbers Say About Credits per Semester

Let’s quantify things. While exact distributions vary by institution and applicant pool, several large‑scale patterns appear consistently in advising data, AAMC reports, and institutional outcomes.

Typical Credit Loads in U.S. Undergraduates

Across broad undergraduate populations (all majors), institutional data usually shows:

- 12 credits – Minimum for full‑time status

- 15 credits – “On track to graduate in 4 years”

- 18+ credits – Overload at many institutions (requires approval)

For premeds who are accepted to medical school, advising offices and internal outcome reports commonly show:

- Median term load: 15–16 credits

- Common “rigorous” terms: 17–18 credits

- Very few successful applicants: average <13 credits/term unless heavily offset by context (e.g., 30–40 hours/week employment)

A Typical Accepted Premed’s Credit Pattern

While individual variation is substantial, a not‑uncommon accepted applicant profile might look like this:

- Freshman year:

- Fall: 14–15 credits (mix of intro science, writing, general ed)

- Spring: 15–16 credits (adds second lab science)

- Sophomore year:

- Fall: 16–17 credits (2 sciences + 1 lab + humanities)

- Spring: 16–18 credits (similar pattern, maybe first upper‑division)

- Junior year (MCAT year for many):

- 1–2 terms at 15–17 credits with heavy upper‑division science

- Possibly one slightly lighter term (13–14) near MCAT test date

- Senior year:

- 15–17 credits per term, often with capstone, advanced electives, and continuing sciences

The important feature is evidence of multiple semesters where the student carries ≥15 credits with 8–11 of those credits in BCPM while maintaining high performance.

“Thresholds” That Raise Questions

No single pattern automatically rejects you, but some course‑load patterns reliably trigger closer scrutiny:

- Repeated 12–13 credit semesters with no documented reason

- Never carrying more than one lab science at a time

- Sudden drops from 16–18 credits to 12 credits concurrent with GPA deterioration

- Short bursts of overload (20+ credits once) sandwiched between very light semesters

Admissions readers statistically know that medical school schedules run closer to the equivalent of 20+ credits of intensive, high‑stakes coursework. If your transcript never comes close to testing that kind of capacity, they look for other evidence (MCAT, post‑bacc work, full‑time jobs) to justify confidence.

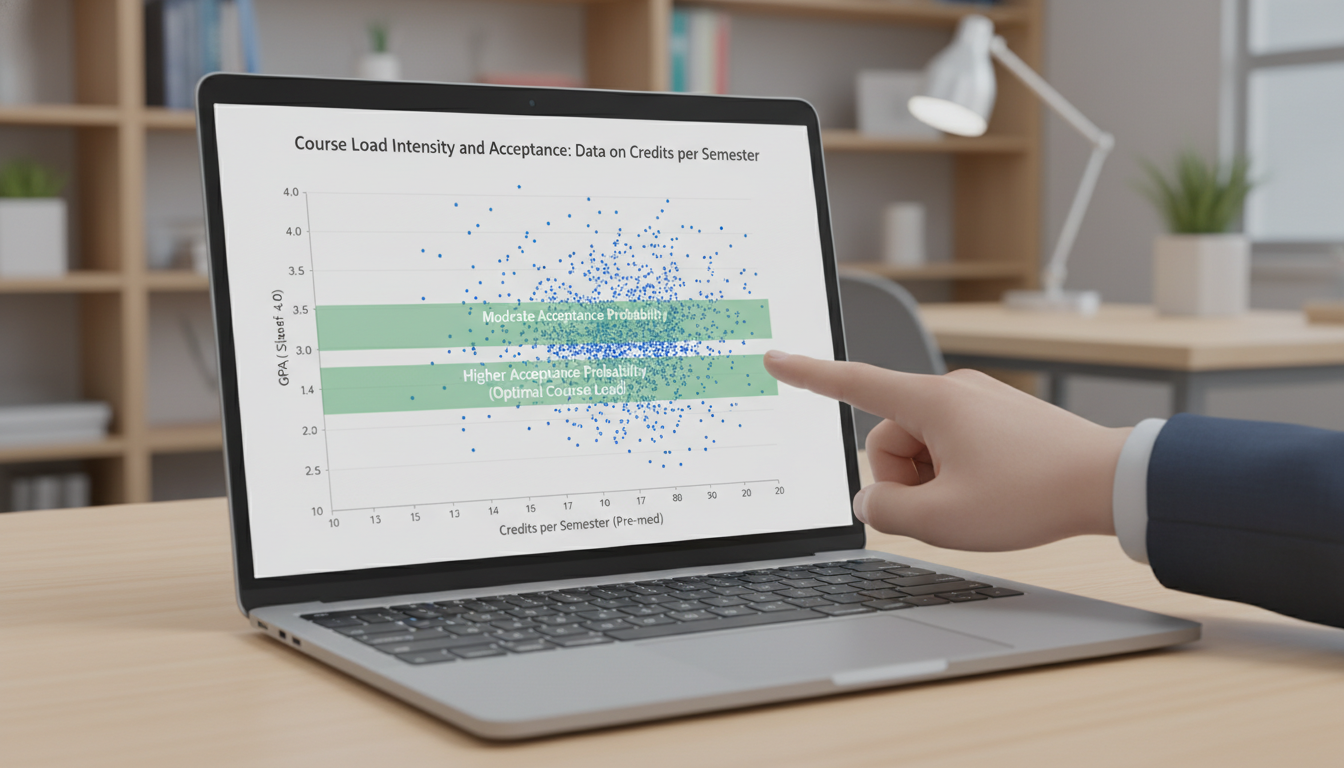

GPA vs. Course Load: Where the Trade‑Off Actually Breaks

The common premed myth is “take the heaviest load you can survive.” The data often tells a different story: after a point, incremental credits buy almost no additional “rigor points” but cost a lot of GPA.

Stylized GPA–Load Relationship

Aggregate advising data from multiple universities often shows a curve roughly like this:

- Students taking 12–14 credits

- Average GPA slightly higher (fewer courses, more focus)

- But if this lighter pattern is continuous, rigor questions arise

- Students taking 15–17 credits

- Slightly lower average GPA vs 12–14 group

- This range is overrepresented among successful med school applicants

- Students taking 18–21 credits

- Average GPA drops more sharply

- Only the top academic performers sustain 3.7+ with this load

Put in rough numeric terms:

- 12–14 credits: average premed GPA cluster might sit around 3.55–3.65

- 15–17 credits: cluster around 3.45–3.60

- 18–21 credits: cluster around 3.30–3.50

These are generalized, but they illustrate the key point: going from 16 credits to 20 does not proportionally increase “rigor signal,” but it frequently drops GPA.

From an admissions probability lens, a 3.8 GPA with several 15–17 credit science‑heavy terms is typically stronger than a 3.45 GPA with multiple 19–21 credit terms.

How Committees Weight Rigor vs. GPA

Informal scoring models used by many schools weight metrics roughly like:

- Overall GPA / BCPM GPA: high weight

- MCAT total and section scores: high weight

- Course rigor and trend (including load): moderate weight

- Institutional context and major difficulty: moderate weight

If you frame it like a utility function:

- A 0.10–0.15 drop in GPA due to an overload usually subtracts more from your “admissions score” than the added credits contribute.

- Moving from “never above 14 credits” to “multiple 15–17 credit terms” does noticeably help your rigor profile without heavily endangering GPA for most students.

From the data, the sweet spot for many successful applicants looks like:

Target band: 15–17 credits during core premed years, with 8–11 BCPM credits in several terms.

Science Load Intensity: Credits Alone Do Not Tell the Whole Story

Total credits per semester is only one dimension. Admissions staff pay particular attention to science density and course level.

Two 16‑credit terms can look wildly different in rigor:

Term A (16 credits):

- Organic Chemistry I + Lab (4)

- Physics I + Lab (4)

- Upper‑division Cell Biology (3)

- Writing in the Sciences (3)

- 2‑credit research seminar (P/F)

Term B (16 credits):

- Intro Psychology (3)

- Public Speaking (3)

- Statistics for Social Science (3)

- General Education Humanities x2 (6)

- 1‑credit fitness course

Raw credits: identical. Signal: dramatically different. Term A reads like a stress test for med school readiness; Term B reads like an interlude.

When schools analyze transcripts, they informally track:

- Number of BCPM credits per term

- Number of upper‑division science courses per term

- Presence of multiple lab courses in the same semester

- Trend: did the student move from lower‑division to sustained upper‑division science intensity?

Data from internal committee rubrics often categorize “rigorous science terms” as those with:

- ≥8 BCPM credits, often with

- ≥1 upper‑division BCPM course

- 1–2 lab components

Successful applicants typically have 3–5 such terms across their junior/senior years and sometimes late sophomore year.

Longitudinal Patterns: Trends Matter More Than Any Single Semester

Admissions decisions are influenced less by any one term and more by the trajectory.

From a time‑series perspective, evaluators look for:

1. Upward or Stable Rigor Trend

Strong patterns often show:

- Early terms: 14–15 credits, 1 major science + 1 supporting course

- Middle terms: 15–17 credits with 2+ sciences, at least one being upper division

- Later terms: sustained high‑level science and similar or slightly higher loads

A student whose record shows:

- Freshman: 13, 14 credits

- Sophomore: 15, 16

- Junior: 16, 17 (heavy science)

- Senior: 15, 16 (capstone + science)

signals a healthy ramp‑up.

2. Recoveries and Explanations

Data anomalies are not automatic red flags if paired with an explanation:

- One 12‑credit term during a documented medical issue or family emergency

- explicit context in personal statement or advisor letter

- One poor term followed by multiple strong semesters at higher or similar load

Readers effectively ask: Is this a one‑off outlier or part of a downward trend?

Repeated light loads, fluctuating credits, and erratic GPA swings with no apparent cause will concern them far more than a single low‑credit, low‑GPA semester.

Optimizing Your Own Course Load Strategy

Instead of aiming for “maximum credits,” the data supports designing a balanced signal portfolio: enough intensity to demonstrate readiness, but not so much that you induce GPA collapse.

Step 1: Establish Baseline Capacity

Use early semesters as calibration:

- Semester 1: 14–15 credits, including 1 lab science and 1 quantitative or writing‑heavy course.

- Semester 2: 15–16 credits, moving toward 2 sciences (one may be non‑lab).

Track your performance. If your term GPA is ≥3.6 and you are not overwhelmed, the data suggests you can safely explore 16–17 credits with more science density.

If you are already struggling below 3.4 with 14–15 credits, simply adding more credits is unlikely to improve your eventual competitiveness. At that point, the data points toward optimizing study strategies and perhaps spreading prerequisites more intentionally.

Step 2: Anchor 3–5 “Flagship” Rigorous Terms

Across your undergraduate or post‑bacc timeline, plan for 3–5 semesters that clearly stand out as med‑school‑like in intensity:

Each such term might look like:

- 16–17 total credits

- 8–11 BCPM credits, with at least:

- 1–2 upper‑division science courses

- 1–2 lab components

- 1 writing‑ or reading‑intensive course for balance

Examples:

- Organic Chem II + Lab, Physiology, Biostatistics, Medical Ethics

- Physics II + Lab, Molecular Biology, Upper‑division Psychology, Writing seminar

You are constructing a visible pattern that signals: “This student has already functionally done mini‑med‑school semesters and thrived.”

Step 3: Use Strategic Lightening, Not Chronic Underloading

Data from successful applicants shows that an occasional strategic lighter term is normal and accepted, especially:

- MCAT study semester: some students drop from 17 to 13–14 credits

- Major leadership or intensive research semester: similar slight reduction

Problems emerge when:

- Multiple consecutive years sit at 12–13 credits, with no balancing context

- The transcript shows no period where you handled multiple advanced sciences simultaneously

Use light terms purposefully and sparingly, and consider documenting the rationale briefly in your application narratives or advisor letter if it is not obvious from your activities list.

Step 4: Combine Course Load with Extracurricular Time Data

Admissions staff implicitly compute a “total commitments” estimate:

Academic load + work hours + research + volunteering + major leadership

For example:

- Student A: 18 credits, almost all science, 3.4 GPA, minimal ECs

- Student B: 16 credits, 3.8 GPA, 10–15 hours/week clinical work, 5–10 hours/week research

From an expected‑value standpoint, Student B’s profile often yields higher interview and acceptance probabilities at many schools, even though Student A has slightly more credits.

The practical takeaway:

- Target healthy but not extreme course load

- Layer in consistent (not sporadic) extracurricular involvement that explains why you did not overload every term

Special Cases: Non‑Traditional and Post‑Bacc Students

For career‑changers, post‑baccs, or students with earlier academic issues, course load intensity can play a corrective or reinforcing role.

Academic Redemption Tracks

For students with an early GPA <3.2, many successful paths involve:

- 2–4 consecutive semesters in a formal or informal post‑bacc or MS program

- Each term:

- 12–15 credits, all or nearly all upper‑division or graduate BCPM

- Strong performance (3.7–3.9+)

In these cases, even a 12‑credit term, if it consists of all advanced science and yields high grades, sends a powerful signal of transformed academic ability. The “rigor score” of a 12‑credit all‑graduate‑science term can exceed that of an 18‑credit mixed term with multiple non‑science electives.

Working Students

For applicants working ≥20–30 hours/week:

- Admissions committees often mentally adjust expectations of credit load.

- A 12–14 credit semester combined with 30 hours/week work can be perceived as equivalent or higher total load than an 18‑credit semester with no job.

The key is documentation:

- List work hours clearly in AMCAS/AACOMAS activities

- Reference these constraints in your personal statement or secondary essays if they help explain lighter terms

From a data standpoint, heavy employment plus full‑time study with good grades is one of the clearest markers of resilience and time‑management capacity.

Concrete Benchmarks: Where You Probably Want Your Numbers

Translating the qualitative trends into approximate quantitative targets:

Target Ranges for Traditional Premeds

If you are a traditional premed (no major academic setbacks, typical 4‑year plan), numbers that align with many successful applicants look like:

- Average term load across college: ~15–16 credits

- Number of terms with ≥15 credits: at least 6–8

- Number of clearly rigorous science‑dense terms: at least 3–5

- Maximum term load: often 17–18 credits, maybe 19 once with strong performance

Paired with:

- Cumulative GPA: ideally 3.7+ for MD‑oriented applicants, ~3.5+ for DO‑oriented (with variation by school)

- BCPM GPA: as strong or stronger than overall GPA

- MCAT: competitive for your target range (for context, national MD matriculant median often falls near 511–512)

When You Should Worry About Course Load Signals

Data and committee feedback suggest closer self‑review if:

- You never exceed 14 credits in any semester

- You never take more than one science course at a time

- Your junior/senior years do not show clear upper‑division science clusters

- Multiple terms at 12–13 credits are paired with minimal work or EC responsibilities

- You have a relatively modest MCAT (<508–509) and lack any strong “rigor” term pattern

Any one of these is not fatal. Several together create a profile that forces schools to assume more risk about your med‑school readiness.

Summary: What the Data Actually Favors

Across thousands of accepted premeds, the patterns that repeatedly emerge are:

- Moderate‑high, sustained course loads (15–17 credits) with science density are far more common in accepted applicants than either chronic underloading or chronic overloading.

- GPA loss from extreme overload usually hurts more than the rigor gain helps. A smaller number of carefully planned “flagship” rigorous semesters, combined with a high GPA, is a more reliable strategy.

- Context and pattern beat raw credit counts. Multiple science‑heavy terms, upward trends, work hours, and post‑bacc performance all inform how committees interpret your credits per semester.

Design your semesters so that any admissions reader, scanning your transcript as if it were a timeline chart, sees clear evidence that you can handle a med‑school‑like workload—and thrive.

FAQ

1. Do I need to take 18+ credits every semester to be competitive for medical school?

No. Outcome data and advising experience both show that most successful applicants do not carry 18+ credits every term. A pattern of 15–17 credits in several science‑dense semesters, coupled with a strong GPA, usually provides ample evidence of rigor. Isolated 18‑credit terms can help, but sustained overloading that drags down GPA tends to reduce acceptance odds.

2. Will medical schools penalize me for a semester with only 12–13 credits?

One or two light semesters, especially with clear context (MCAT prep, health issue, heavy work or family responsibilities, major leadership role), rarely hurt you when the rest of your record shows strong performance under more typical loads. Concerns arise when multiple semesters sit at 12–13 credits with no offsetting explanation and no periods of clear science intensity.

3. Is it better to take more science courses with a slightly lower GPA, or fewer science courses with a higher GPA?

From an admissions‑probability standpoint, the data generally favors fewer but well‑mastered courses over constant overload that suppresses GPA. You need enough science intensity to demonstrate readiness—usually 3–5 strong, science‑heavy terms—but once that signal is established, each 0.1 of GPA is usually more valuable than each extra credit of marginal rigor.

4. How do gap‑year or post‑bacc courses factor into perceptions of course load?

Post‑bacc and SMP/gap‑year coursework often carries disproportionate weight, especially if your earlier record was weaker. Committees look for 12–15 credits of upper‑division or graduate‑level science per term with high grades as evidence of current academic ability. Even at 12 credits, if all are advanced sciences with A‑level performance, the rigor signal can be very strong and can partially compensate for lighter or weaker earlier undergraduate terms.