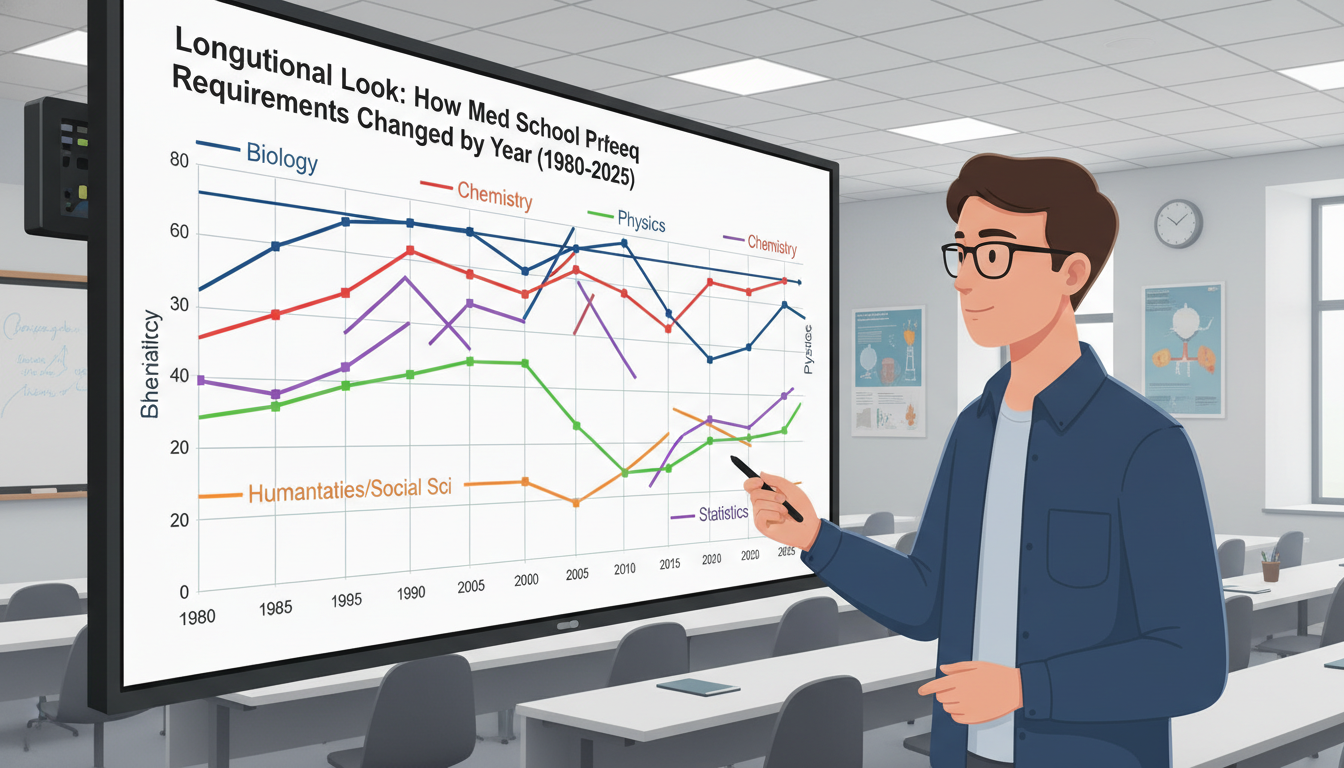

The data shows a simple truth: medical school prerequisites have steadily shifted from rigid course checklists to outcome-based competency expectations, and that shift accelerates more every decade.

For premeds, this is not an abstract policy story. It determines which classes you take, how you spend your summers, and whether your transcript raises red flags. Understanding how requirements have changed over time is the best way to predict where they are heading and how to plan now.

Below is a longitudinal, data-driven look at how U.S. medical school prerequisite requirements have evolved by era, with specific emphasis on:

- Which courses used to be “must-have” versus “nice-to-have”

- How the MCAT redesign in 2015 rewired requirements

- The rise of competencies, flexibility, and holistic review

- What the trendline suggests for applicants between now and 2030

(See also: How Many Clinical Hours Do Accepted Pre‑Meds Actually Have? The Numbers for more details.)

Where possible, I will anchor this to quantitative shifts: number of required semesters, percentage of schools with specific requirements, and dates of major structural changes. Some figures are approximate, derived from AAMC data summaries, LCME standards, and longitudinal analyses of the MSAR and public med school admissions pages.

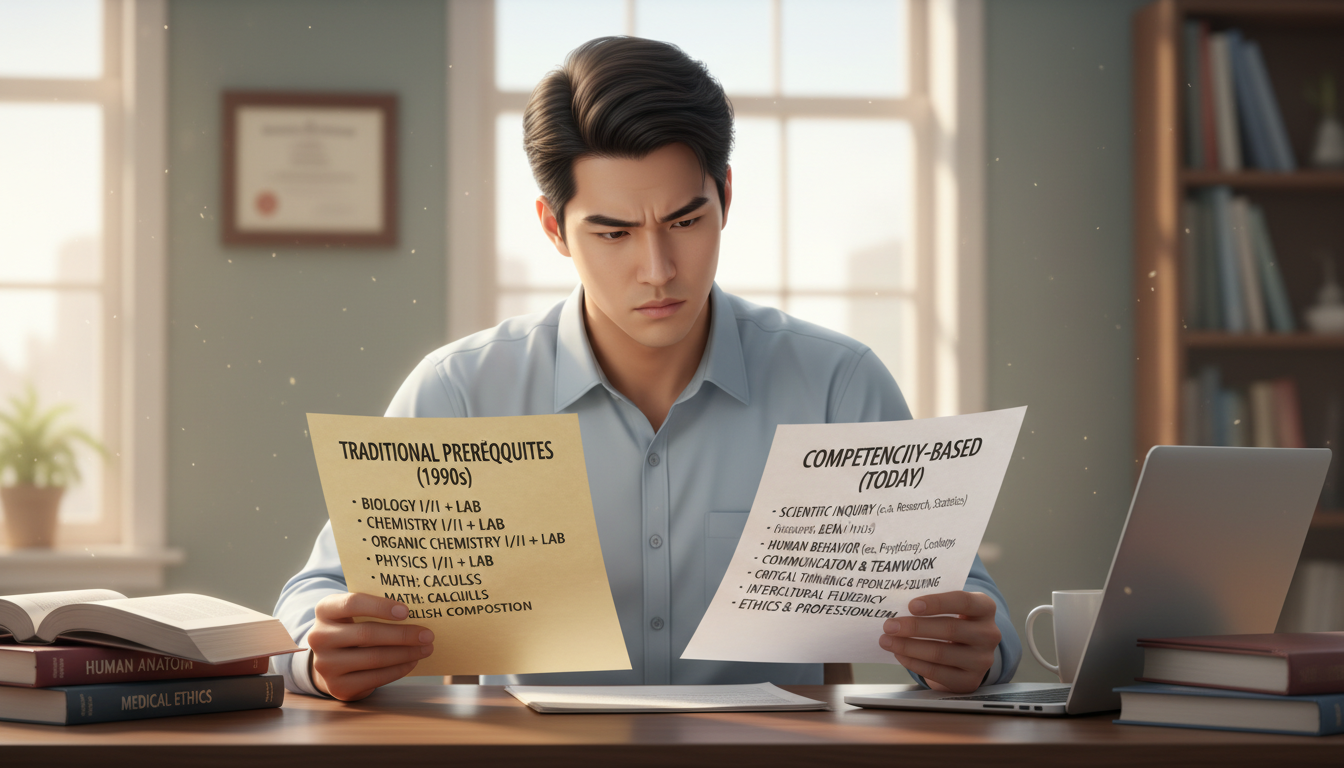

1. The 1970s–1990s: The Age of the Uniform Science Checklist

From the mid‑20th century through the 1990s, the typical U.S. medical school prerequisite profile was remarkably consistent. The data from archived AAMC reports and MSAR entries show that the overwhelming majority of schools converged on a nearly identical science-heavy template.

Standard pre-2000 requirement pattern

By the late 1980s and early 1990s, roughly 80–90% of MD programs required all of the following:

- Biology: 1 year (2 semesters) with lab

- General / Inorganic Chemistry: 1 year with lab

- Organic Chemistry: 1 year with lab

- Physics: 1 year with lab

- English / Writing: 1 year (composition and/or literature)

Less common but still notable:

Mathematics:

- ~40–60% of schools required at least 1 semester of calculus

- ~10–20% explicitly accepted statistics as an alternative, but calculus dominated

Biochemistry:

- Before the 1990s, only a minority of schools required it (often 10–20% range), though many listed it as “strongly recommended”

In practice, a competitive premed in 1990 usually completed:

8–10 semesters of lab science + 2 semesters of English + 1–2 semesters of math.

That is roughly 11–14 prerequisite courses, not counting “recommended” items.

The instructional model driving this was linear: learn basic sciences in college → apply them in med school → become a clinician. Admissions requirements mirrored that linearity.

Limited flexibility, limited diversity

These rigid prerequisites had measurable consequences:

Course sequencing was tightly constrained.

A typical timeline:- Year 1–2: Gen Chem + Biology → Org Chem + Physics

- Year 3: MCAT (based heavily on these courses)

Deviating from that path was risky.

Non-science majors faced barriers.

A humanities or social sciences major still had to stack 8+ lab science semesters, often forcing heavy overloads or 5th years.Math emphasis skewed toward calculus.

The requirement data showed a clear preference for calculus, despite its limited direct application in clinical medicine, while statistics—arguably more useful for evidence-based medicine—was an afterthought.

The core message from the data: between about 1970 and 2000, the national variation in prerequisites was low. Geography, ranking, and public/private status did not meaningfully alter the basic checklist.

2. 2000–2014: Slow Erosion of Uniformity, Rise of Flexibility

Between 2000 and the MCAT overhaul in 2015, the prerequisites began to fragment. It did not happen overnight; you see a gradual erosion of uniformity in the data.

Changing course requirements by the early 2010s

By around 2010–2014, aggregated school requirement patterns show:

Biology: Still nearly universal, but with nuance

- ~90%+ of schools required at least 2 semesters

- More programs began specifying content (e.g., molecular biology, genetics)

General Chemistry: Remained near-universal

- Typically 2 semesters with lab

Organic Chemistry: Still widely required, but softening

- Instead of 2 full semesters everywhere, some schools began accepting:

- 1 semester organic + 1 semester biochemistry

- Integrated “Chemistry for the Life Sciences” sequences

- Instead of 2 full semesters everywhere, some schools began accepting:

Physics: Slight decline in strictness

- Many schools still listed 2 semesters with lab

- A noticeable fraction of schools allowed algebra-based, non-calculus physics

Math: The pivot from calculus to statistics began

- Proportion requiring calculus alone decreased

- More schools allowed “calculus or statistics”

- Some high-tier schools began explicitly emphasizing statistics as preferred

Biochemistry: Moved from “recommended” to “quasi-required”

- By the early 2010s, a growing subset of MD programs required 1 semester of biochemistry or accepted it in lieu of 2nd semester organic chemistry.

The net effect: the average applicant still needed ~10–12 prereq courses, but the composition started to change.

Early signals of competency-based language

Admissions pages from this era started including language like:

- “Applicants should demonstrate competence in basic biological principles…”

- “Course requirements may be fulfilled by advanced courses that presume introductory material…”

This was a key structural change: the shift from seat time in a particular course to demonstrated mastery. Initially, this was vague. However, it aligned with:

- The 2009 AAMC–HHMI report “Scientific Foundations for Future Physicians”

- Growing emphasis on evidence-based medicine and data literacy

- Increasing recognition that rigid course lists discouraged nontraditional and diverse applicants

The data here are mainly qualitative (wording of prerequisites), but systematically, the frequency of words like “competency,” “flexibility,” and “recommended rather than required” clearly rose between 2005 and 2014.

3. 2015: The MCAT Redesign as a Structural Break

From a longitudinal standpoint, 2015 is an inflection point. The MCAT change does not just add a section; it reshapes course expectations.

What changed in MCAT content

The April 2015 MCAT introduced major shifts:

New section: Psychological, Social, and Biological Foundations of Behavior

- Heavy coverage of psychology and sociology concepts

Reweighted emphasis on:

- Biochemistry

- Molecular and cellular biology

- Research methods and statistics

- Critical analysis of social and behavioral determinants of health

Immediately after the MCAT redesign, AAMC surveys and institutional policy updates show several quantitative effects over the next 3–5 years:

Psychology and Sociology requirements/recommendations

- Pre‑2015: Only a very small minority of MD schools explicitly required psych or soc (low single-digit percentages).

- By ~2018:

- A significant fraction (estimates often 20–35%) recommended at least 1 semester each of psychology and sociology for MCAT prep and foundational understanding.

- A smaller but growing subset began requiring 1 semester of behavioral or social sciences, allowing psych/soc/public health courses to count.

Biochemistry as a de facto expectation

- Post-2015, a substantial majority of MD programs either:

- Formally required 1 semester of biochemistry, or

- Labeled it as “strongly recommended and typically completed by successful applicants.”

- You can interpret this practically as: across the applicant pool, completion rates for biochemistry moved toward near-universal.

- Post-2015, a substantial majority of MD programs either:

Statistics and research methods

- With the MCAT’s emphasis on data interpretation and experimental design, more schools:

- Accepted statistics in place of calculus

- Recommended coursework in statistics, epidemiology, or research methods

- By the late 2010s, a meaningful subset of schools highlighted statistics more prominently than calculus.

- With the MCAT’s emphasis on data interpretation and experimental design, more schools:

In regression terms, you can think of 2015 as an exogenous shock that shifted the coefficients on certain prerequisites:

- Effect size large and positive for: biochemistry, psychology, sociology, statistics.

- Effect size mildly negative for: organic chemistry (especially full 2‑semester sequences as a strict requirement).

4. 2015–2024: From Checklists to Competencies

The dominant trend over the last decade has been clear in the MSAR data and admissions websites: formal course requirements are slowly shrinking; competency expectations and recommended preparation are expanding.

Snapshot of current patterns (circa early‑mid 2020s)

Based on aggregated admissions page reviews and AAMC MSAR data patterns, the “typical” MD requirement set today looks more flexible than 20 years ago:

Biology

- Almost universal expectation, usually 2 semesters.

- Many schools specify content areas (cell biology, genetics, physiology) rather than exact courses.

Chemistry

- Still nearly universal, but often described as:

- 2 semesters of general/inorganic + 1 semester organic + 1 semester biochemistry

- or an integrated chemistry sequence with biochem content

- Fewer schools rigidly demand “2 semesters of organic with lab.”

- Still nearly universal, but often described as:

Physics

- Still widely expected, but a notable subset shifted to:

- “Physics appropriate for science majors” (without specifying number of semesters), or

- One year “recommended” rather than absolute requirement.

- Still widely expected, but a notable subset shifted to:

Biochemistry

- De facto standard component of preparation.

- Required or equivalent competencies expected at a large majority of schools.

Math / Statistics

- Some schools still list “1–2 semesters of mathematics” but:

- Calculus is less often mandatory.

- Statistics is frequently accepted and sometimes preferred.

- Some schools still list “1–2 semesters of mathematics” but:

Psychology and Sociology / Behavioral Sciences

- More schools now list 1 semester of behavioral or social science as required or strongly recommended.

- Even when not required, nearly all admissions guidance suggests preparation aligned with MCAT behavioral content.

English / Writing / Communication

- The strict “2 semesters of English” has softened:

- Some schools accept writing-intensive courses in other disciplines.

- Others emphasize “proficiency in written and oral communication,” with examples rather than fixed English series.

- The strict “2 semesters of English” has softened:

Fewer hard requirements, more holistic language

A clear numerical trend emerges if you track the number of hard prerequisites:

- 1990s typical: 10–14 fixed course requirements (lab science, math, English).

- Early 2010s: still ~10–12, with some flexible substitutions.

- Early‑mid 2020s:

- Some schools retain a long list of required courses.

- Many others list 4–6 formal requirements plus an extended set of “recommended” courses and competencies.

Common competency domains now highlighted include:

- Biological and biochemical foundations of living systems

- Chemical and physical foundations of biological systems

- Psychological, social, and behavioral foundations of health

- Critical thinking, quantitative reasoning, and data analysis

- Cultural competence and understanding of healthcare systems

Underrepresented and nontraditional applicants benefit from this shift. More schools explicitly allow:

- Advanced coursework to substitute for intro sequences.

- Community college credits, with caveats.

- Post-bacc work to demonstrate competencies even if the original major was far from science.

From a data analyst’s lens, variance between schools is higher than in any prior decade. Two top 25 MD programs may have completely different formal requirement lists, despite converging on similar competency expectations.

5. Year-by-Year Application Implications: 2020–2030

Most premeds reading this care less about historical trivia and more about forward-looking guidance. The historical data helps build that forecast.

2020–2024: Where we are now

For applicants in the early‑mid 2020s, the data suggests a robust “safe baseline” that works at the majority of MD programs:

- Biology: 2 semesters with lab

- General Chemistry: 2 semesters with lab

- Organic Chemistry: 1–2 semesters with lab

- Biochemistry: 1 semester

- Physics: 2 semesters with lab (for maximum compatibility)

- Math/Stats: 1 semester calculus + 1 semester statistics (or at least statistics)

- English / Writing: 2 writing-intensive courses (not necessarily labeled “English”)

- Psychology and Sociology: 1 semester each or combined behavioral/social science coverage

For DO programs, patterns are similar, though some schools explicitly maintain more traditional lists.

However, if you model the constraints as optimization with a wide school list, redundancy appears. Many high-quality programs would consider applicants missing one of the traditional pieces (e.g., second semester of organic chemistry) if their overall preparation and MCAT performance demonstrate competency.

2025–2030: Extrapolating the trendline

Projecting forward based on current trajectories and accreditation trends yields several likely outcomes:

Further de-emphasis of rigid course counts

- Expect more schools to phrase requirements as “competencies” with multiple ways to meet them: traditional courses, advanced study, formal post-bacc work, or possibly structured online coursework.

- The number of schools clinging to 8+ rigidly specified lab science semesters as formal requirements will likely shrink.

Continued rise of statistics, data literacy, and population health

- As evidence-based practice and big data become even more central, statistics and epidemiology will likely shift from “recommended” to “strongly expected” at many schools.

- Some may explicitly require “a course in statistics or biostatistics.”

More weight on social and structural determinants of health

- Courses in sociology, psychology, anthropology, public health, or health policy may be more explicitly required or at least heavily recommended.

- Schools will look for applicants who understand disparities, systems of care, and behavioral factors that influence outcomes.

Integrated and interdisciplinary premed pathways

- Institutions that offer structured “premed tracks” within non-science majors (e.g., health humanities, global health) will increasingly align these tracks to competencies rather than old-fashioned course checklists.

- Double-counting (one course satisfying both a major requirement and a competency) will be more common.

How to operationalize this as a current premed

Given the variability and evolving policies, a data-driven strategy includes:

Construct a school-specific matrix

- Select 20–30 target schools (a mix of reach, match, safety).

- Create a spreadsheet with rows = schools, columns = courses/competencies (bio, gen chem, orgo, biochem, physics, psych, soc, stats, English, etc.).

- Fill in: Required / Recommended / Not listed.

- Your goal is to cover ≥90% of “Required” cells and the majority of “Strongly recommended.”

Weight the probability of acceptance vs. marginal course cost

- If only 2 out of 25 target schools require a second semester of organic chemistry, and both are “reach” schools, the marginal utility of that extra course is lower.

- If 18 out of 25 recommend biochemistry and 15 recommend statistics, those are high-leverage courses to prioritize.

Monitor policy updates annually

- The last 10 years show that requirement language can change year-to-year, especially for newly added behavioral and data-related coursework.

- Re-check requirements the summer before applying, not just when you start college.

6. Key Takeaways Across the Decades

Looking longitudinally, three main patterns emerge:

From rigidity to flexibility

- In the 1980s–1990s, medical school prerequisites were highly standardized: ~10–14 specific courses, primarily lab sciences plus English and math.

- From 2000 onward, schools gradually loosened rigid course counts and introduced flexibility in how applicants could demonstrate preparation.

Shift in content emphasis

- Traditional pillars (biology, chemistry, physics) remain, but:

- Biochemistry, psychology, sociology, and statistics have gained prominence, particularly after the 2015 MCAT redesign.

- Organic chemistry’s grip as a 2‑semester requirement has weakened; a combination of organic + biochem is now more typical.

- Behavioral and social sciences, plus communication and data literacy, are now clearly in the core preparation set.

- Traditional pillars (biology, chemistry, physics) remain, but:

Competencies as the new organizing framework

- The trajectory of admissions language points away from seat time in specific classes and toward demonstrated skills and knowledge domains.

- Holistic review and diversity goals reinforce this: schools aim to admit candidates with varied academic backgrounds who still meet shared scientific and professional competencies.

For premeds, the actionable implication is clear: do not rely on outdated “standard premed” templates. Use current data from your target schools, align your courses with the competencies the modern physician actually needs, and treat historical patterns as context for where requirements are heading—not as a fixed blueprint.