Extended Time to Graduation: Is It Really a Career-Ending Red Flag?

What actually happens to the fourth-year who took six years to finish med school—do they secretly get auto-screened into the trash pile, or do they still match into real, decent programs?

Let me ruin the drama: extended time to graduation is a yellow flag, not an automatic death sentence. It can hurt you. It often does if you handle it badly. But the myth that “needing an extra year = no residency, ever” is flat-out wrong.

The more accurate version is uglier and less click‑friendly: “Needing extra time forces programs to ask why—and your outcome depends almost entirely on how good that answer is, how your record looks after the delay, and which specialties and programs you target.”

You are not doomed. But you also do not get to hand‑wave it away with “personal reasons” and hope no one notices. They will notice.

Let’s separate the superstition from the data and the actual behavior of selection committees.

What Programs Really See When They Notice Your Extended Time

Most students imagine some dramatic reaction: dean’s office whispers, PDs glaring, an ERAS portal that flashes “DEFECTIVE APPLICANT” when your grad date is 6 years instead of 4.

Reality is more boring and more nuanced.

Programs see three things:

- Timeline mismatch – Your med school duration is longer than typical (5, 6, sometimes 7+ years).

- Context – Any listed leaves, repeat years, remediation, research years, dual degrees.

- Trajectory – What happened to your performance after the disruption.

They do not see “this person is lazy” or “this person is broken” automatically. That’s not how serious PDs think. They see a question: “Is this an unstable applicant or a resilient one?” Then they start looking for evidence.

Here’s the harsh part: if your story is incoherent, evasive, or full of ongoing issues, they will assume the worst. If it’s specific, consistent, and backed by improved performance, most rational programs move on.

The Different Flavors of Extended Graduation (And How They’re Treated)

Lumping every delay into the same “red flag” bucket is lazy thinking. Programs don’t actually do that. They discriminate—hard—based on why and what happened next.

Let’s break the main categories down.

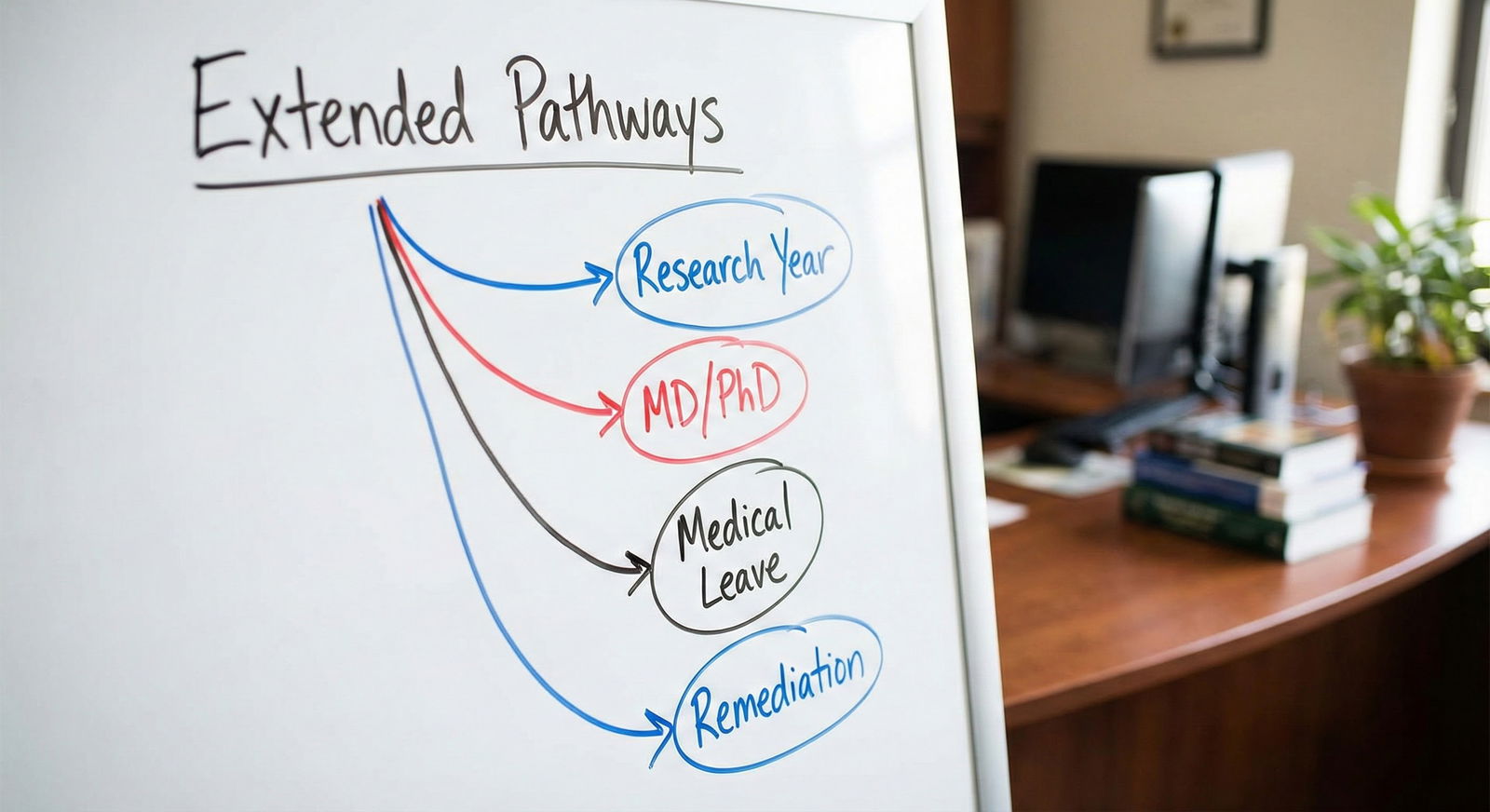

1. Planned, structured extra time (research year, MD/PhD, dual degree)

This is the most misunderstood category by anxious students and the least worrisome to programs.

If you took a research year with a structured program, published, presented at conferences, and your evaluations remained strong, most PDs don’t call this a red flag at all. In some fields (derm, rad onc, ENT, ortho), a research year is basically standard currency.

MD/PhD or MD/MPH with planned extra years? Nobody caring about quality calls that a “problem.” It’s a different track, not a delay.

2. Genuine medical / personal leave with clean documentation

You had cancer. Your parent died and you were the primary caregiver. You had a major depressive episode and took time off, got treated, and returned stable with good performance.

Model PD thinking: “They went through hell, took appropriate leave, came back, and now their record looks solid. This is a resilient person who uses help appropriately.”

Is it scrutinized? Yes. Is it auto‑reject? No. The question becomes: is the issue resolved, and does your later performance prove it?

3. Academic difficulty / remediation / repeating a year

This is the one everyone is really asking about. You failed courses or a clerkship. Maybe failed Step 1 or Step 2. You had to repeat a year or extend to remediate.

This is a real red flag, but again, not equally fatal for everyone. Programs care about three things:

- Was the problem localized (e.g., early didactic struggle, then strong clerkships)?

- Did you improve? Clear upward trend or just barely scraped by again?

- Did you own it in your explanation, or do you blame everyone else?

I’ve watched admissions meetings where someone with an early failure and then honors‑level clerkships got ranked ahead of a “clean” but mediocre applicant. Consistent mediocrity is not magically better than struggle followed by excellence.

4. Chaos: multiple failures, inconsistent stories, ongoing issues

This is the truly dangerous zone. Not because of the duration alone, but because the extended time is just the visible symptom of underlying instability.

Multiple leaves. Repeated USMLE/COMLEX failures. Chronic professionalism issues. Vague, shifting explanations.

That combination, yes, can absolutely wreck your application. But again, notice: the time to graduation is not the core problem. It’s all the other stuff dragging behind it.

What the Data Actually Shows (Not the Rumor Mill)

Students talk like programs are scanning “time to graduation” as a primary filter. They aren’t. They filter on exam failure, visa status, IMG status, Step 2 scores, and sometimes school tier. Extended time is secondary.

We don’t have a perfect public dataset saying “X-year med school → Y% match rate,” but we do have real patterns from NRMP and program behavior:

- US MD seniors, even with blemishes, still match at high rates when they apply smartly. The overall US MD senior match rate 2024 sits around the mid‑90% range.

- Single USMLE failures reduce match rates, but they don’t drop them to zero. Many of those failures come bundled with repeat years or extensions. People still match—into FM, IM, peds, psych, pathology, prelim surgery, etc.

- Specialty competitiveness matters far more than “5 vs 4 years.” Trying to break into plastics with multiple repeats is obviously brutal. Applying IM or FM with one repeated year and then strong clerkships? Very possible.

Here’s the part most people miss: plenty of extended‑time students silently match every year. You don’t hear from them because they’re busy starting intern year, not posting their private history on Reddit.

To make this concrete:

| Extension Type | Impact on Competitive Fields | Impact on Core Fields (IM/FM/Peds/Psych) |

|---|---|---|

| Planned research or dual degree | Often neutral or positive | Neutral |

| Single medical/personal leave | Mild concern | Usually manageable |

| Single repeated year, improved | Moderate concern | Often manageable with strategy |

| Multiple failures, ongoing issues | High barrier | Difficult but not impossible |

Notice the pattern: the reason and trajectory matter more than the raw number of years.

The Part That Actually Makes or Breaks You: The Story + The Receipts

Programs are not mind readers. All they see is your application and how you talk about it.

If you extended your time and then pretend it didn’t happen, you look evasive. If you overshare every painful detail, you overwhelm people and raise liability flags. There’s a narrow middle lane that actually works: candid, concise, and backed by evidence.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Reason clarity | 90 |

| Post-leave performance | 95 |

| Exam outcomes | 85 |

| Specialty choice | 70 |

| Letters of rec | 80 |

How to frame the extension without sabotaging yourself

You need three components.

A clear, concrete reason

Not a melodrama, not a mystery novel. Just enough detail to show it was real, and that it’s resolved or controlled.Bad: “I extended for personal reasons that are now resolved.”

Better: “During my second year, I developed a depressive episode that significantly impacted my academic performance. I took a formal medical leave, completed treatment, and returned with continued outpatient follow‑up. Since then, I’ve passed all courses and clerkships on first attempt and scored a 240 on Step 2.”Evidence of stability and improvement

This is where applicants either win or lose. You say you’re “better”? Show me.- Strong Step 2 score after earlier struggles

- Clerkship grades trending up (passes → high passes → honors)

- Consistent narrative from your dean’s letter / MSPE

Third‑party validation

Programs don’t fully trust your self‑assessment. Nor should they.You want letters that implicitly or explicitly say: “Yes, they had a stumble; no, it’s not who they are now.” When I see a letter from a medicine chair saying, “I would have no hesitation hiring this person as my own resident,” I stop caring nearly as much about an old extension.

Specialty Reality Check: Where Extended Time Hurts Most (and Least)

Some specialties barely flinch at an extra year. Others live in fantasyland where everyone is a 260+ robot who finished in 4 years with 3 grants and 7 first‑author papers.

You can guess which is which.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Derm/Plastics/ENT/Neurosurg | 95 |

| Ortho/Rad Onc/Urology | 85 |

| EM/Anesthesia/Gen Surg | 70 |

| IM/FM/Peds/Psych/Neuro | 40 |

| Pathology/PM&R | 30 |

High‑prestige, ultra‑competitive specialties care a lot about any signal of risk. Extended time combined with exam struggles is usually fatal there unless you bring insane compensating strengths (serious research, elite letters, connections). But that’s not news: those fields are ruthless even with clean records.

Core specialties—IM, FM, peds, psych, neuro, path, PM&R—tend to be more pragmatic. They evaluate the whole picture. Your extension matters, but your Step 2, clinical performance, and letters matter more.

The smartest thing you can do is align your ambitions with your record. Refusing to adjust specialty plans after multiple fails and a 7‑year MD? That’s not “grit.” That’s denial.

How to Handle Extended Time Strategically in Your Application

The myth is that you should hide it. Or over‑confess it. Both are bad strategies.

Here’s the approach that actually works in real-world selection meetings.

1. Be proactively honest in the right places

You have three main tools:

- ERAS “Education Interrupted” / leaves section – Brief factual note.

- Personal statement (short paragraph, max) – Only if it’s central to your arc.

- Advisor / dean’s letter alignment – Your story must match what’s in your MSPE.

Think of it like this: if your extension is obvious (and it usually is), you must address it somewhere in a controlled way. Otherwise, programs fill in the blanks with their worst assumptions.

2. Don’t turn your whole application into a therapy session

Your personal statement is not your psychiatrist. The goal is not emotional catharsis. The goal is to show growth with receipts.

One tight paragraph is usually enough:

- Briefly state the problem.

- State the concrete action (leave, treatment, remediation).

- Show objective improvement.

- Pivot back to who you are as a clinician.

If I finish your PS feeling like I know your pathology more than your strengths, you overshared.

3. Back your story with a strong “after” picture

Programs look at the most recent data as the best predictor.

If your extension was M2 and now your M3/M4 clerkships are honors with excellent narrative comments and a solid Step 2? That’s a strong recovery story.

If your extension was M4 because you kept failing Step 2 until the last minute and scraped a barely passing score? Different story. Same duration, very different signal.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Extended Time to Graduation |

| Step 2 | Red Flag - Assumptions of Instability |

| Step 3 | Ongoing Concern - High Risk |

| Step 4 | Likely Rejection from Hyper-Competitive Fields |

| Step 5 | Viable Candidate with Good Framing |

| Step 6 | Reason Clear and Legitimate? |

| Step 7 | Post-return Performance Strong? |

| Step 8 | Specialty Choice Realistic? |

That’s basically how PD brains process you—quick mental flow like this.

The Ugly Truth About Stigma (And Why It’s Not Absolute)

Let’s not pretend bias doesn’t exist. It does.

Some faculty still have a 1980s mindset: “I finished in four years with no days off, why couldn’t they?” They see any deviation as weakness. You will run into that attitude. You cannot perfectly fix it.

But the modern reality is this: mental health leaves, family crises, and nonlinear paths are vastly more common and more openly documented than a generation ago. Programs know this. They’ve watched residents burn out, relapse, and quit because they didn’t take time when they should have.

So smart PDs ask a different question: Is this someone who recognized a problem, addressed it, and demonstrated stability afterward? Or is this someone who will implode under stress with no insight?

Your job is to present yourself firmly in the first group.

If you treat your extension as a shameful secret, you actually validate the stigma. If you treat it as a specific challenge you worked through—and then you show me excellence afterward—you rewrite the narrative.

When Extended Time Really Does Block You (For Now)

There are situations where extended time plus other factors make matching this cycle unlikely:

- Multiple failed attempts at Step 1 and Step 2, with barely passing scores.

- Extended time plus significant ongoing health instability.

- A pattern of professionalism issues documented in your MSPE.

- No meaningful upward trend anywhere.

That’s when you stop asking, “Is extended graduation a red flag?” and start asking, “What do I need to change before I apply again?”

For some, that means a dedicated extra year to stabilize health before residency. For others, it means recalibrating specialty, doing a prelim year, research, or focusing on building a cleaner, stronger recent track record.

Extended time is not the villain. It’s the visible symptom. If you do not fix the underlying issues and then demonstrate sustained improvement, no framing trick will save you.

The Bottom Line

Extended time to graduation is not a career-ending mark. It is a forced transparency test.

Three key points:

Programs care far more about why you extended and what your record looks like afterward than the raw number of years. A coherent, specific, and documented story with a strong upward trajectory is often acceptable—sometimes even impressive.

Your specialty choice and application strategy matter more than the delay itself. Hyper-competitive fields may be off the table; core specialties remain very much in play if you’re realistic and your recent performance is strong.

You cannot hide or melodramatically confess your extension; you must frame it briefly, honestly, and back it with evidence of stability and competence. Do that, and you’re a viable candidate with a yellow flag, not a walking rejection.