The harsh truth: an extra research year rarely fixes a bad application by itself. It can absolutely help—sometimes a lot—but used in the wrong situation, it just delays the same Match outcome by 12 months.

Let’s sort out when a research year is actually worth it and when it’s just expensive procrastination.

The Core Question: What Are You Trying To Fix?

Before you even think about a research year, you need brutal clarity on your real problem. “My app isn’t competitive” is not specific enough.

Here’s what a research year can meaningfully improve:

- Lack of research for research-heavy specialties (derm, rad onc, plastics, neurosurg, ortho in some places)

- Weak academic profile with time to generate strong output (Step 2 still open, potential for honors/AOA, strong institutional support)

- Limited connections/mentorship in your desired specialty

- A previous unsuccessful Match where your main deficit was academic productivity or specialty-specific engagement

Here’s what a research year usually does NOT fix:

- Multiple exam failures (Step 1, Step 2, COMLEX)

- Pattern of low clinical evaluations or professionalism concerns

- Major red flags (dismissal, LOA for non-medical professionalism issues)

- Terrible interview skills or poor communication

- Completely unrealistic specialty choice (e.g., 210-215 Step 2 trying to salvage derm with a quick research year)

If your main red flag is exam failure or professionalism, research is dressing up the wrong problem. You may need a different strategy: extra clinical time, remediation narrative, strong Step 2, targeted letters, or changing specialty.

When a Research Year Is Worth It

Here’s where I’ve seen a research year pay off in a real way.

1. You’re Trying for a Hyper-Competitive Specialty

If you’re targeting:

- Dermatology

- Plastic surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Orthopedic surgery

- ENT

- Radiation oncology

- Interventional radiology (in some programs)

…then yes, a research year can move the needle—if done right.

In these fields, programs want:

- A clear, long-standing commitment to the specialty

- Substantial, specialty-specific research

- Strong letters from known people in that field

A good research year here looks like:

- One full year in a lab or outcomes group within that specialty

- Multiple projects where you’re first or second author

- Presentations at national specialty meetings

- Daily contact with faculty who write top-tier letters

A bad research year:

- Work in a random lab unrelated to your target specialty

- You’re “helping” others on endless projects with no first-author anything

- No conference presentations

- No strong advocate who can call PDs and say, “Take this person”

If you can’t line up that first version, pressing pause may not be your best move.

2. You Failed to Match, but Your File Is “Almost There”

If you went through a full ERAS cycle and:

- Got some interviews in your target field (not zero)

- Feedback from mentors is: “You’re close; you just need more research or time in the field”

- Your scores are okay for the specialty (not stellar, but in range)

…then a research year can be a smart, targeted repair move.

Your goals during the year:

- Double down on that specialty at one institution or a well-known lab

- Build 3–5 solid projects with at least 1–2 accepted/published by next application season

- Get evaluated clinically (if possible) by faculty in that department

- Have at least one faculty member ready to say on the phone: “We should really rank this person highly”

If instead your pre-match file had:

- No interviews at all

- Several exam failures

- Weak or generic letters

Then you need a more global fix than “do research for a year.”

3. You Have a Clear Path to High-Quality Output

Research years pay off when productivity is real, not theoretical.

Ask these questions before you commit:

- Is there a specific mentor who has a track record of residents/students matching well after working with them?

- Are there ongoing projects you can join that are already in progress (so you’re not starting at zero)?

- Will you have protected time, or are you actually doing half-clinic, half-research with no real ownership?

If your likely output in a year is:

- 0–1 poster

- 0 publications, maybe 1 “manuscript in progress”

That’s not fixing anything. You can get that level of output during med school.

On the other hand, in a well-run research year I’ve seen:

- 2–4 first-author papers

- 5–10 total publications/presentations

- Meaningful connections with national names

Those years change trajectories.

When a Research Year Is a Bad Idea

Let me be blunt. I’d strongly caution against a research year in these scenarios:

1. You Have Serious Exam Red Flags

Examples:

- Multiple Step 1 or Step 2 failures

- Very low Step 2 (e.g., barely passing, or far below specialty norms)

- Pattern of COMLEX failures for DO students

No amount of PubMed padding hides failed boards. PDs check that first.

Your energy is better spent on:

- Dedicated, structured exam remediation

- Potentially taking Step 2 (if not yet taken) and crushing it

- Building a realistic specialty strategy: maybe shifting from derm to IM, from ortho to FM, etc.

Research is optional. Passing boards is not.

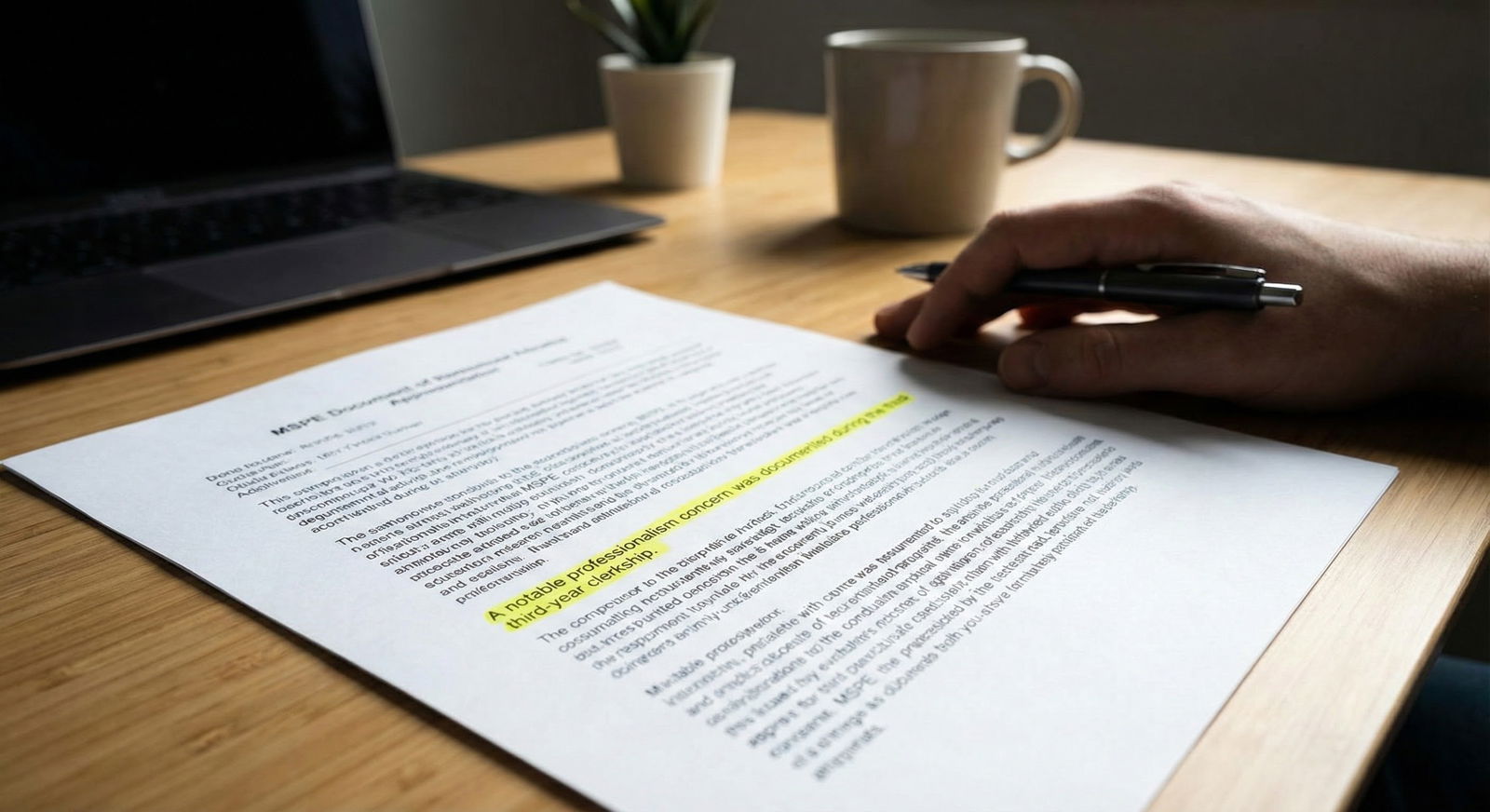

2. Your Problem Is Professionalism or Clinical Performance

If you:

- Had remediation for unprofessional behavior

- Have lukewarm or concerning MSPE comments (“requires close supervision,” “interpersonal challenges”)

- Got “Pass” on almost all rotations with specific negative feedback

A year in a lab doesn’t prove you’re safe and effective with patients.

Better options:

- Additional sub-internships with stellar performance

- More time in clinical settings with documented improvement

- Strong letters that directly address concerns: “I supervised this student in high-stress clinical environments; they were excellent.”

3. You Just Feel Behind Compared to Your Classmates

Comparison is a terrible reason to take a research year.

“I only have 2 abstracts and my classmate has 12 pubs” is not a problem in most fields.

For many core specialties (IM, FM, peds, psych, EM, gen surg at mid-range programs), you do not need a dedicated research year if:

- You have decent scores

- No failures

- Solid clinical evaluations

- A handful of research/quality projects or even none, depending on the field

A research year there adds delay and financial strain with limited upside.

Financial and Life Costs You Shouldn’t Ignore

People love to hand-wave the cost of a research year. That’s a mistake.

Typical realities:

- You’re often paid little or nothing. Maybe a small stipend.

- You lose one year of attending salary long-term.

- You may add more loan burden to survive the year.

- Burnout can get worse if you’re doing something you don’t actually enjoy.

You should be able to answer:

- “Am I okay pushing my income and career back by one year for a realistic chance of improving my Match outcome?”

- “Do I like research enough to do this full-time for 12 months without hating my life?”

If the honest answer is no, you need a different fix.

What Programs Actually See When They Look at a Research Year

PDs are not stupid. They recognize repair attempts. They mentally translate “research year” as: “They’re buying time to fix something.”

That’s not automatically bad. But they’ll look for:

| Scenario | Likely PD Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Strong productivity + strong letters | Genuine commitment; positive repair |

| Minimal output + generic letter | Box-checking; no real change |

| Research unrelated to specialty | Confused narrative; unclear goals |

| Research after exam failures only | Avoiding core issue; still risky |

So your job is to make the story tight:

- “I realized I love [specialty]. I took a structured research year in [X department], produced [Y], and here’s how that made me a stronger applicant and future [specialist].”

Not:

- “I took a year because my friends said I needed more research and I hope this helps.”

How to Decide: A Simple Framework

Here’s the decision tree I use with students.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Considering Research Year |

| Step 2 | Focus on Exams/Change Specialty |

| Step 3 | Research Year Likely Worth It |

| Step 4 | Risky: May Not Help Much |

| Step 5 | Fix Other Red Flags First |

| Step 6 | Competitive Specialty? |

| Step 7 | Scores/Exams in Range? |

| Step 8 | Failed to Match? |

| Step 9 | Access to High-Quality Mentor? |

| Step 10 | Main Gap = Research/Connections? |

If you can’t honestly land on “Research Year Likely Worth It” with that logic, don’t default to it just because you’re anxious.

If You Do It, Do It Right: Non-Negotiables

If you decide on a research year, treat it like a high-stakes job, not a gap year.

You should lock down:

- A specific mentor with a track record of getting students/residents into good programs

- A written plan for projects and approximate timelines

- Clear expectations: authorship, hours, conferences, possible clinical time

Your measurable targets:

- At least 2–3 publications or in-press manuscripts by application time

- Several abstracts/posters (ideally national meetings)

- One or two letters from well-known faculty who can advocate for you

And you should absolutely:

- Keep or get some clinical exposure (volunteer clinics, shadowing, perioperative observation) so you don’t look “out of touch” clinically

- Be ready to clearly explain in your personal statement and interviews: Why the research year, what you learned, and how it prepared you for residency

Honest Examples: When It Helped vs. When It Didn’t

I’ve watched both scenarios play out.

Helped:

- MS4 with mid-240s Step 2, good clinical scores, but very light derm exposure. Took a derm research year at a major academic center, 4 first-author papers, 2 national presentations, superstar letter from PI. Matched derm after previously not even applying. The year changed their competitiveness.

Didn’t help:

- Student with multiple Step 1 and Step 2 failures, aimed for ortho. Took “research year” in a random surgical outcomes lab; 1 poster, 0 publications, letter from a junior faculty nobody knew. Applied again to ortho, got no interviews. Ended up switching to a less competitive field after losing a year and a chunk of money.

Mixed:

- FM-bound student with average scores and no red flags, anxious because classmates had 10+ pubs. Took a research year out of fear. Matched FM solidly—but would almost certainly have matched without the year. Financially and time-wise, not worth it.

Quick Self-Check: Is It Worth It for You?

Answer these out loud or on paper:

- What’s the primary weakness in my application? (Be specific.)

- Does a research year actually target that weakness directly?

- Could I fix this in another way (more rotations, stronger letters, exam improvement, changing specialty)?

- Do I have a concrete plan for high-quality research, not just “I’ll find something”?

- If the research year doesn’t change my outcome, will I still feel it was worth it for my long-term goals?

If you’re hand-waving through answers 1–4, don’t sign a research position contract yet.

FAQ: Extra Research Year and Residency Applications

1. Will a research year erase my Step 1 or Step 2 failure?

No. It can soften the blow if everything else is strong and your research is excellent, but exam failures remain front and center. Fixing test performance (or adjusting your specialty target) matters more than collecting publications.

2. Do I need a research year for internal medicine, family medicine, or pediatrics?

Usually not. For most IM/FM/peds programs, a research year is optional. Solid scores, good clinical performance, and strong letters carry far more weight. Research helps mainly for top academic IM programs or specific fellowships later (cards, GI, heme/onc), but you can build that during residency too.

3. How many publications make a research year “worth it”?

There’s no magic number, but for a full 12-month dedicated year in a competitive field, I’d aim for at least 2–3 first- or second-author papers plus several presentations. If your realistic ceiling is one poster and a “manuscript in preparation,” that’s weak justification for the time and cost.

4. Does unpaid vs. paid research year matter to programs?

Programs mostly care about output and letters, not your paycheck. Paid positions are nicer for you, but from a PD’s perspective, productivity, impact, and commitment are what matter. That said, be careful about taking unpaid roles that don’t give you real responsibility.

5. I’m an IMG—does a research year in the US help me?

It can. Especially if it’s in your target specialty at a reputable US institution with clear chances for publications and strong US letters. But for IMGs, US clinical experience (observerships/externships) and strong scores often move the needle more than pure research, unless you’re going for academic-heavy programs.

6. What if I hate research but “need” it for my specialty?

If you truly hate research, reconsider the specialty. Many of the most research-obsessed fields (derm, rad onc, some surgical subs) expect you to engage with research long-term. Forcing yourself into a year you despise just to chase a specialty is a red flag for future burnout.

7. When during med school should I do a research year if I choose to?

Most people do it after core clerkships and before final year (between MS3 and MS4). That way, you’ve confirmed your specialty interest, have some clinical context, and can still use the year’s output in your ERAS application. Taking it too early (pre-clinical) risks doing lots of research in a field you later abandon.

Open a blank page and write two lists: on the left, your real application weaknesses; on the right, how a research year would specifically address each one. If the right column is vague, thin, or doesn’t match the left, your next step isn’t a research year—it’s fixing the actual problem.