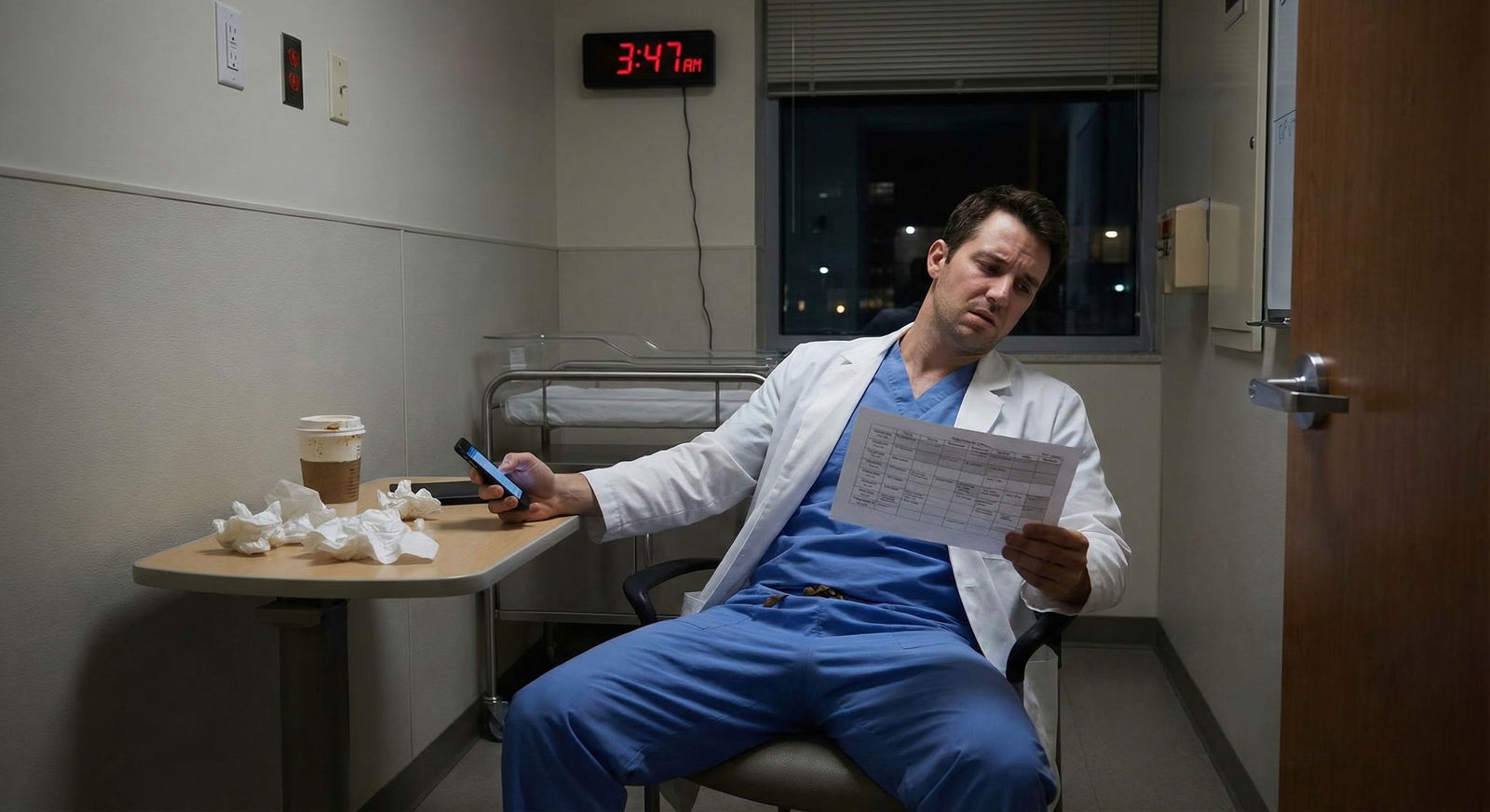

It’s July 1st, 5:10 a.m. You’re in an ill‑fitting set of program‑logo scrubs, badge still stiff, standing in a locker room that smells like stale coffee and chlorhexidine. And you already know: this place has problems.

You saw hints on interview day. Heard rumors from upperclassmen. Maybe the current residents seemed exhausted and vague. Maybe the PD dodged every question about wellness. But you still ranked it. You still matched. And now you’re here.

This is not about whether you “should have ranked differently.” That ship sailed on Match Day. The question in front of you is much sharper:

How do you survive — and quietly assess your options — in the first month at a residency program that already shows red flags?

Let’s walk through what to do, week by week and situation by situation.

Step 1: Get Very Clear on What the Red Flags Actually Are

Before you decide how to act, you need to name what you’re actually dealing with. “Bad vibes” is not a plan.

Common red flags I’ve seen new interns walk into:

- Chronic duty hour violations disguised as “we’re just a hard‑working program”

- Malignant leadership (punitive, retaliatory, or openly disrespectful)

- Lack of supervision (you’re operating way above your level)

- Patient safety issues that everyone shrugs off

- Toxic culture: gossip, bullying, racism/sexism, or “eat their young” mentality

- Bait‑and‑switch around schedule, education, or research promises

In your first week, keep a running list on a private, secure note (not on hospital devices, not on shared workstations). For each “red flag,” jot:

- What actually happened

- Date / rough time

- Who was involved

- Any concrete consequence (for you or the patient)

You’re not building a legal case today. You’re building clarity. There’s a huge difference between “I hate this place” and “I did 95 hours last week, and my senior told me to chart that I left at 7 p.m. when I left at 10:30 p.m.”

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Duty Hours | 30 |

| Supervision | 20 |

| Culture | 25 |

| Safety | 15 |

| Education | 10 |

Step 2: First 72 Hours – Stabilize Yourself Before You Fix Anything

The first three days are not the time to start “fixing the program.” You’re not the hero. You’re the intern who barely knows how to log into Epic.

Your goals in the first 72 hours:

- Learn the actual work.

- Map the people.

- Keep your mouth shut more than you want to.

Learn the actual work

You’re going to be tempted to focus on how dysfunctional everything feels. Fight that impulse, just for a few days.

Instead:

- Learn the call system, paging, order sets, signout templates.

- Figure out where things physically are: pharmacy window, supply room, night float office.

- Watch who actually runs the service (often the chief, not the PD; the unit clerk, not the attending).

Being competent with the day‑to‑day buys you two critical things in a rough program: respect and room to say “no” later when it matters.

Map the people

On day one, you’re trying to classify people quickly:

- Safe, decent human beings who clearly try to help

- Neutral/unknown — could go either way

- Obviously toxic or checked out

You don’t have to be perfect. Just start noticing.

You will see the same names over and over: the senior who quietly helps everyone, the attending everyone dreads, the nurse who knows everything. Mentally flag the helpful ones. You’ll need them.

Step 3: Recognize When It’s “Bad but Tolerable” vs. “Not Safe”

Not every red flag means you must flee. Some just mean: “This will be a grind, protect yourself.” Others mean: “If you stay in this exact situation, someone will get harmed — maybe you.”

Here’s a crude but useful mental split.

| Type | Concerning But Possibly Tolerable | Dangerous / Act Sooner |

|---|---|---|

| Duty hours | 70–80 hr weeks, but logged honestly; occasional spillover | 90+ hr weeks, pressure to falsify hours |

| Supervision | Busy attendings, reachable but not present | You’re making high‑risk decisions alone |

| Culture | Negativity, burnout, some sniping | Bullying, slurs, threats, retaliation |

| Safety | Occasional near‑misses taken seriously | Serious errors shrugged off or hidden |

| Education | Weak teaching, few conferences | Being forced into unsupervised procedures |

If your experience is mostly in the “concerning but possibly tolerable” column, plan for survival and adaptation while you quietly reassess long‑term fit.

If you’re mainly in the “dangerous” column in week one, your strategy shifts. You’re no longer just surviving. You’re collecting information, protecting your license, and looking at exit options.

Step 4: Build a Micro‑Network Fast (Without Oversharing)

In a red‑flag program, isolation kills you. The instinct is to withdraw, do your work, and go home. That’s how you end up feeling trapped.

Your first‑month priority: find 2–3 people you can at least partially trust.

Targets:

- A senior resident who seems competent and not cruel

- A co‑intern who looks as uncomfortable as you feel

- A nurse or unit clerk who has “seen everything” and is still kind

You’re not trauma‑dumping. You’re doing three things:

Asking practical questions.

“How do people usually handle cross‑cover here?”

“Is it normal for signout to run this long?”

“Where do residents go when they’re drowning?”Testing how they talk about the program.

If every second sentence is “this place is malignant” but they offer no concrete examples, that’s venting, not data.

If they say, “Cards is fine, but avoid Dr. X; he yells and throws things,” that’s more actionable.Watching if they keep your questions to themselves.

If you ask one resident a simple question and it comes back around the grapevine twisted, they’re not your person.

You want a micro‑network, not a gossip circle.

Step 5: Protect Yourself From Day One (Documentation and Boundaries)

If you’re in a program with red flags, you have to assume two things:

- If something goes wrong, they may blame the lowest person (you).

- Nobody will remember details accurately when it’s convenient not to.

So you quietly protect yourself.

What to document (and how)

Use a private, secure method — personal notebook kept at home or an encrypted note app on your own phone. Not on hospital systems.

Log:

- Date, rotation, and shift type

- Major issues: unsafe staffing, lack of supervision, pressure to lie, serious safety events

- Who was involved and what was said, as close to verbatim as you can recall

Example: “7/7, night float, MICU. I called Dr. Smith twice about hypotensive patient, no answer. Senior said: ‘Just push more fluids, he doesn’t like to be woken up.’”

You are not writing this to show anyone yet. You’re giving your future self receipts if things escalate.

Micro‑boundaries that matter

No, you cannot remake the culture in July. But you can do a few small but critical things:

- Don’t falsify duty hours. Log them accurately. If pressured, you can note: “Attending X told me to adjust hours” in your private log.

- Don’t sign notes or orders you’re uncomfortable with just to avoid conflict. Ask for clarification. Document when you tried to escalate concerns in the chart (professionally).

- Don’t agree to “just say you did the exam” when you didn’t. That’s your license, not theirs.

You can say things like:

“I’m not comfortable documenting that since I didn’t directly evaluate this,”

or

“I’d feel better if we clarified the plan with the attending.”

Is it annoying to some seniors? Sure. But it’s much less painful than being the name on the chart when an investigation happens.

Step 6: Quietly Map Your Exit Options (Without Torching Bridges)

Here’s the harsh truth: transferring residency is possible, but not quick or guaranteed. But you don’t have to decide in week one. What you should do in the first month is simple: understand what levers exist.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Notice red flags |

| Step 2 | Document and seek help |

| Step 3 | Survive and assess |

| Step 4 | Talk to trusted senior or chief |

| Step 5 | Stay and adapt |

| Step 6 | Explore transfer |

| Step 7 | Build network and boundaries |

| Step 8 | Reassess after 3-6 months |

| Step 9 | Safety at risk? |

| Step 10 | Improves? |

| Step 11 | Still unacceptable? |

In the first month, do this:

Read your specialty board and ACGME requirements.

Know what must be true for your program to remain accredited. Know duty hour rules, supervision requirements, and what’s clearly out of bounds.Quietly talk with a trusted advisor from med school (not affiliated with your current program).

Someone who can tell you, “This is normal pain” vs. “No, that’s actually not okay.”Understand the transfer landscape.

Transfers usually happen:- After PGY‑1 into PGY‑2 spots that open

- Into programs that lost residents or expanded late You do not need to start emailing PDs in week one, but you should mentally accept: “If I need to get out, it’ll take months and I’ll need strong documentation and decent evaluations.”

Don’t threaten to transfer. Don’t tell your co‑interns you’re “definitely leaving.” That just paints a target on your back.

Step 7: Use the Chain of Command Strategically (Not Emotionally)

At some point, you’ll hit something you can’t just swallow. Chronic duty hour lies, repeated unsafe staffing, actual harassment. When that happens, the instinct is either explode or shut down.

Neither helps.

The first‑month rule: test lower‑risk channels before you go nuclear.

Who you can approach, in increasing order of escalation:

- A senior you trust: “Is this normal for this rotation? I’m worried because…”

- A chief resident: “Here’s what’s happening on nights; I’m concerned it’s not sustainable or safe.”

- Program coordinator: logistical or policy clarifications, not drama.

- Program director: only when you’re clear, calm, and have specific examples.

- GME office / DIO / institutional ombudsperson: if local attempts fail and the issue is serious (safety, harassment, clear ACGME violations).

When you do escalate, do it like this:

- Be specific: “Over the last two weeks, I’ve worked three 28‑hour shifts, with active clinical work past hour 24, and been asked to log them as 24. Here are the dates.”

- Be calm: “I’m not trying to cause trouble, but I’m worried this is not compliant and is unsafe for patients.”

- Be focused on systems, not personalities: “The current cross‑cover setup leaves one intern with 60 patients overnight.”

If you go in saying, “This place is malignant, everyone is toxic,” you’ll be written off as “that dramatic intern.”

Step 8: Take Care of Your Brain Chemistry, Not Just Your Schedule

This part gets dismissed as “wellness” fluff, but it’s not. In a bad program, your mood and sleep become your only real defense.

In the first month:

Protect sleep like a procedure.

Blackout curtains, earplugs, white noise. No doom‑scrolling in bed. Post‑call: food, shower, bed. Not “just one episode” of anything.Move your body a little, not perfectly.

Ten‑minute walk after signing out. A few pushups or stretches at home. You’re not training for a marathon; you’re reminding your brain you’re alive.Watch your alcohol and stimulant use.

Red‑flag programs breed coping habits that turn into problems: nightly “decompression” drinks, extra coffee piling on top of 5 hours of sleep. Set rules for yourself now.If you’re spiraling, talk to someone outside the program.

Use physician mental health resources, teletherapy, or your school’s alumni services if they exist. You want at least one person who isn’t on your evaluation committee to hear the unfiltered version.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Clinical Work | 55 |

| Sleep | 25 |

| Commute/Meals | 8 |

| Admin/Notes | 7 |

| Personal Time | 5 |

If you’re having persistent thoughts like “I don’t care what happens to these patients” or “If I got into a car accident that put me in the ICU, I’d be relieved,” that’s not just burnout. That’s danger. You need professional help, not more “resilience.”

Step 9: Decide What You’re Doing With the Rest of the Year — But Not in Week One

By the end of your first month, you should have answers to three questions:

- Is this place simply grueling, or actually unsafe?

- Are there at least a few people here who make it bearable?

- Can I see myself functioning here for a year while I quietly explore options?

If your answers are:

- “Grueling, yes. Unsafe, mostly no.”

- “Yes, a few good people.”

- “I can function, but I might look elsewhere.”

Then your first‑month strategy succeeded. You move into medium‑term planning: optimize rotations, find mentors, build your CV, and — if needed — start exploring PGY‑2 openings in 6–12 months.

If your answers are:

- “There are sustained safety issues or harassment.”

- “No one feels remotely safe or supportive.”

- “I’m already at the edge of my mental health.”

Then your next step is not “gut it out.” It’s:

- Document everything (if you haven’t been).

- Talk to a trusted outside mentor.

- Consider formal reporting channels and start learning the transfer process.

You’re not a failure for leaving a harmful situation. I’ve watched excellent residents move and thrive elsewhere. I’ve also watched people “tough it out” in truly malignant environments and spend years undoing the damage.

Step 10: What to Actually Do Tomorrow Morning

You still have to walk onto the floor tomorrow. So here’s your 24‑hour survival script.

Tonight:

- Spend 10 minutes writing down what bothered you this week, with specifics.

- Identify one person you’ll ask for a practical tip tomorrow (senior, nurse, chief).

- Decide one boundary you’ll hold tomorrow — maybe “I will not lie on duty hours,” or “I will ask for help if I don’t understand an order.”

Tomorrow:

- Show up on time, prepared, and focused on learning your patients cold. Clinical competence is armor.

- Ask your one planned question. “Hey, what’s your strategy for staying ahead on notes here?” It opens doors.

- Log out on time if you reasonably can. If you can’t, note why. Is it your inefficiency or systemic overload? There’s a difference.

After your shift:

- Do one non‑medicine thing: short walk, call a friend, trashy TV, whatever. 20 minutes.

- Add anything major to your private log.

- Then stop thinking about the program for the rest of the night. You need at least a few hours where this place doesn’t occupy your entire brain.

Looking Ahead

You matched where you matched. That part is fixed. But what happens over the next month — and whether this red‑flag program becomes a survivable chapter or a slow‑motion disaster — is not fixed.

In the coming months, you’ll have more data. You’ll see other services, other attendings, other residents. Some of your worst impressions may be confirmed. Some might soften. You may decide to stay and carve out a workable niche. You may quietly prepare to move.

For now, your job is simple and hard:

Stay safe. Stay observant. Get competent. Build a tiny circle of decent people. And keep one eye on the exits without tripping over your own feet.

Once you’ve made it through this first month with your sanity and your reputation intact, you’ll be in a much stronger position to decide what comes next — whether that’s adapting inside this program or writing the first email that starts your way out. That longer‑term play is another strategy entirely.

FAQs

1. How soon is “too soon” to start thinking about transferring?

You can start gathering information in month one — reading ACGME rules, understanding transfer mechanics, reconnecting with med school mentors. That’s fine. Actually reaching out to other program directors usually makes more sense after you’ve completed at least one rotation and have some evaluations, unless the situation is truly dire (eg, clear harassment, blatant safety violations, or you’re at serious mental health risk). Give yourself at least a few weeks to separate “normal intern misery” from “this place is genuinely unsafe.”

2. Will speaking up early get me labeled as a problem resident?

Depends how you do it. If you charge into the PD’s office on day three saying “This place is malignant,” yes, you’ll get labeled. If you start by asking seniors and chiefs for context, gather specific examples, and present concerns in calm, concrete language focused on patient safety and compliance, you’re much harder to dismiss. Use the chain of command. Avoid emotional rants in email. And do not vent about leadership in group texts that can be screenshotted and forwarded.

3. How do I tell if I’m just overwhelmed as an intern versus the program actually being bad?

Ask yourself this:

If you magically felt well‑rested and more confident, would your main complaints disappear? If so, you’re mostly dealing with the standard “intern shock.” On the other hand, if even at your best you’d still be uncomfortable with the level of supervision, the way people are treated, or the pressure to cut ethical corners, that’s the program, not you. Cross‑check with a few sources: a senior in your program you trust, a mentor from med school, and your own written log of specific incidents. Patterns over time are more honest than how you feel after one brutal call night.