Most students waste 90% of their shadowing time because they do not know how to think in differentials while watching real patients.

You are not there just to “observe what doctors do.” You are there to steal their diagnostic frameworks.

Let me break that down specifically: every single patient you see is a live differential diagnosis exercise. If you walk out of shadowing with only a vague idea of “the doctor was really nice” and “I saw some cool diseases,” you have missed the real educational gold.

This applies whether you are:

- A premed just trying to understand what medicine is

- An early medical student who has not started formal clinical rotations

- Someone in a structured pre-clinical shadowing program

You can start practicing differential diagnosis thinking long before you ever write “Assessment and Plan” in a chart. You just have to structure what you watch, what you write down, and what you ask.

1. Reframing Shadowing: From Passive Watching to Clinical Pattern Training

Most shadowing advice is about etiquette: arrive early, dress properly, do not touch patients. That is necessary but shallow.

The real leverage comes from using shadowing as:

- A pattern-recognition lab

- A live OSCE (Objective Structured Clinical Examination) where you never get pimped but can still test yourself

- A repeatedly reset diagnostic simulation, with zero risk to the patient and huge upside for you

The mindset shift: every patient = one structured case

Before you shadow your next session, commit to treating each encounter as a “mini case presentation” with these elements:

- Chief complaint

- Key history points

- Focused exam findings

- Working differential

- Tests ordered and why

- Final diagnosis (if revealed)

- What you missed or did not consider

That is your template. You will not fill every box perfectly. That is fine. But using this structure regularly builds the same mental scaffolding that strong clinicians rely on daily.

2. The Three-Tier Note System: How to Capture Diagnostic Lessons in Real Time

You cannot learn differentials from shadowing if you rely on memory only. You will forget specific presentations, exact phrases, and why particular diagnoses were ruled out.

You need a simple, repeatable note system that:

- Respects patient privacy

- Does not interfere with the encounter

- Lets you reconstruct the case later

Tier 1: In-room shorthand (ultra-brief, de-identified)

Use a small notebook without patient names or identifiable details. For each encounter, capture:

- Age range and sex: “M 40s,” “F 70s”

- Chief complaint in 3–6 words: “chest pain exertion,” “new cough 2wks,” “leg swelling R”

- 3–5 key features you notice:

- Duration: “3d,” “6mo”

- System: “GI,” “neuro,” “cardiac”

- Red-flag style phrases you hear the physician pursue: “weight loss? night sweats?”

- Any striking exam component: “S3?” “focal weakness L arm”

Example Tier 1 note:

F 50s – RUQ abd pain

2d, worse post-meal, N/V

+Murphy sign

Labs ordered, RUQ US

No name, no specific time or date, no identifiable job/location. This keeps you on safe ground for privacy.

Tier 2: Post-clinic structured case write-up

Within 24 hours, expand each shorthand note into a case skeleton using a fixed format. For example:

- Demographics: F ~50s

- Chief complaint: Right upper quadrant abdominal pain

- History highlights:

- Duration: 2 days

- Worse after fatty meals

- Associated nausea, vomiting

- No fever mentioned (unclear)

- No mention of jaundice

- Physical exam pearls:

- Localized RUQ tenderness

- Positive Murphy sign

- No generalized peritonitis described

- My differential at the time:

- Cholelithiasis

- Acute cholecystitis

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Hepatitis

- What the physician did:

- Ordered RUQ ultrasound

- Ordered CMP, CBC, lipase

- Gave analgesia, antiemetic

- Teaching or explanation noted:

- Explained Murphy sign as stopping inspiration due to pain

- Outcome (if known):

- Ultrasound positive for gallstones + wall thickening (probable acute cholecystitis)

Do this for 3–5 cases per session. You do not need to document all 20 patients you see. Focus on:

- Common high-yield complaints (chest pain, shortness of breath, abdominal pain, headache)

- “Weird” cases that surprised you

- Cases with rich teaching moments

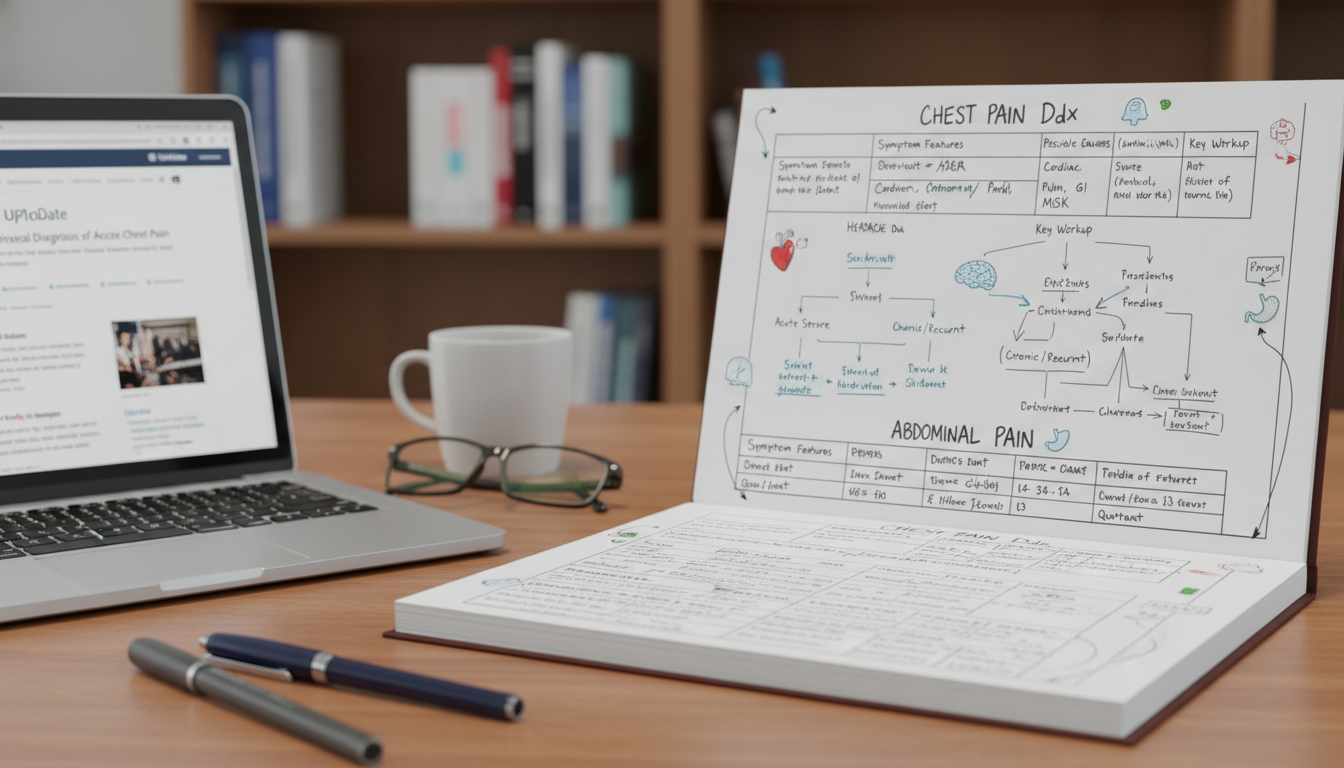

Tier 3: Weekly differential diagnosis review

Once a week, sit down for 45–60 minutes and review your collected cases. This is where real diagnostic learning happens.

For each case:

- Ask: What is the prototypical differential for this chief complaint?

- Compare your differential to:

- UpToDate

- AMBOSS

- First Aid (for big categories, if you are early)

- A focused book like “Symptom to Diagnosis” (Stern)

- Expand your list into:

- Emergent / must not miss

- Common and likely

- Less common but important

For RUQ pain, your structured differential might become:

- Emergent/must not miss:

- Acute cholecystitis

- Ascending cholangitis

- Perforated peptic ulcer

- Common/likely:

- Biliary colic

- Hepatitis

- Pancreatitis (esp. if pain radiating to back)

- Less common but important:

- Right lower lobe pneumonia

- Renal colic (if flank-to-groin radiation)

- Herpes zoster (if rash appears)

You are transforming a single shadowing encounter into a reusable differential template you will recognize instantly on Step 2, shelf exams, and in clinical years.

3. Training Your Brain to Think in Differentials During the Actual Encounter

You will NOT be diagnosing patients as a premed or early student. That is non-negotiable. But you can absolutely be running your own internal silent “clinical reasoning simulation” in parallel with the physician.

Stepwise internal process during each patient

As soon as the chief complaint becomes clear, mentally lock it in:

- “52-year-old man with chest pain”

- “23-year-old woman with headache”

- “68-year-old man with confusion”

Then follow this pattern:

- Immediately generate 3–5 possibilities before more data:

- Chest pain: STEMI, NSTEMI, PE, aortic dissection, GERD, costochondritis

- Headache: Migraine, tension, SAH, meningitis, temporal arteritis (if older), cluster

- Watch very intentionally:

- Which questions does the physician prioritize?

- What do they skip entirely?

- Where do they suddenly slow down and dig deeper?

These patterns reveal the real clinical reasoning they use.

Example: Chest pain visit in urgent care

Your mental notes:

- Initial differential: ACS, GERD, costochondritis, anxiety, PE

- Physician starts with:

- Character (“pressure vs sharp”)

- Exertional? Radiation? Associated diaphoresis or nausea?

- Personal and family cardiac history

- Travel, immobilization, hormone therapy (PE risk)

What is happening here? They are trying to:

- Separate life-threatening (ACS, PE, dissection) from benign

- Identify risk factors that change pre-test probability

Write down later: “For chest pain, physician focused heavily on exertional nature, risk factors, and radiation. Did NOT obsess over exact pain score number.”

This creates a pattern in your head:

- Chest pain → “Is this cardiac or not?” as first fork

- Then → “If cardiac, is it urgent/emergent or stable?”

Over dozens of patients, you will start predicting which questions are coming next. That is your diagnostic intuition forming.

4. Turning Physician Behavior into Diagnostic Algorithms

One of the most powerful exercises for extracting diagnostic lessons from shadowing is converting what you see the physician do into explicit decision trees.

You do not need formal algorithm software. A notebook margin works.

Example: The “acute headache” algorithm you can steal from three patients

Say in one shadowing week you see:

- Patient A: 25-year-old with severe unilateral pulsating headache + photophobia → treated as migraine

- Patient B: 60-year-old with new onset worst headache of life → sent to ED for CT head to rule out SAH

- Patient C: 35-year-old with fever, neck stiffness, confusion → sent emergently to ED for meningitis evaluation

After reviewing your notes and correlating with resources, you derive:

Step 1 – Immediate red flags

Ask mentally:

- Sudden thunderclap onset?

- Neurologic deficits?

- Fever, neck stiffness, altered mental status?

- Age >50 with new headache?

- Immunocompromised?

If yes → consider SAH, meningitis, intracranial hemorrhage, temporal arteritis → emergency evaluation.

Step 2 – Pattern of benign primary headaches

If no red flags:

- Migraine features: unilateral, pulsating, photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, worsened by activity

- Tension: bilateral, band-like, not aggravated by routine activity, mild-moderate

- Cluster: severe unilateral periorbital pain, tearing, nasal congestion, occurring in clusters

You did not invent this algorithm from a textbook. You reverse-engineered it from live clinical practice and then aligned it with formal resources. That cements it much deeper.

Repeat this process for:

- Shortness of breath

- Abdominal pain by quadrant

- Syncope

- Palpitations

- Fever of unknown origin

- Back pain

- Dizziness

Each shadowing block becomes a mini-syllabus of symptom-based differentials.

5. How to Ask Questions That Reveal the Physician’s Diagnostic Logic

Weak question: “What did the patient have?”

Strong question: “When you first saw this patient, what were the main things you were worried about and how did you rule them out?”

You want to expose the timeline of their thinking, not just the endpoint.

Ask at the right time

- DO NOT interrupt in the room.

- DO NOT derail the clinic flow for long teaching sessions.

- DO carry a list of 3 questions per session to ask between patients or at the end.

Good strategies:

Case-specific diagnostic questions

- “For that patient with shortness of breath, what were the most dangerous diagnoses you were considering first?”

- “You ordered a D-dimer but not a CT pulmonary angiogram immediately. What findings would have pushed you to order imaging right away?”

- “You seemed especially concerned when the patient mentioned ‘tearing chest pain to the back.’ Was that because of aortic dissection?”

Meta-reasoning questions

- “What do you focus on in the first 30 seconds of hearing a chief complaint?”

- “In your specialty, what symptoms make you most anxious because they are easy to miss but dangerous?”

Pattern recognition questions

- “How did you distinguish between GERD and cardiac chest pain in that last patient?”

- “When do you start thinking about autoimmune causes instead of just infection or malignancy?”

Write down their answers verbatim in your Tier 2 notes whenever possible. These become “attending pearls” you can review later.

6. Building a Shadowing-Based Differential Diagnosis Portfolio

Most students let their shadowing experiences dissolve into vague memories. You can instead build a tangible portfolio that will:

- Support more intelligent answers on medical school interviews

- Give you real clinical stories that are anchored in diagnostic reasoning

- Serve as a preclinical study resource once you start school

Core components of your portfolio

- Symptom-based case log

Organize your expanded case write-ups by chief complaint rather than by date:

- Chest pain: 6 cases

- Headache: 7 cases

- Abdominal pain: 9 cases

- Shortness of breath: 5 cases

- Joint pain: 4 cases

For each symptom category, summarize:

- Common diagnoses you have actually seen

- One or two “zebra” cases

- Key red-flag features that changed management

- Differential diagnosis templates

For each major symptom, keep a one-page structured differential list divided into:

- Emergent / must not miss

- Common / likely

- Less common but significant

Populate these from:

- Your shadowing cases

- Your weekly review with evidence-based resources

“Reasoning pearls” section A separate section where you collect short, high-yield statements you heard from physicians. For example:

- “Chest pain that is reproducible with palpation is almost never cardiac, but do not ignore risk factors.”

- “In older patients with new headache and jaw claudication, think temporal arteritis until proven otherwise.”

- “If a patient looks sicker than their vitals, think about sepsis or occult bleeding.”

Risk factor maps After enough cases, you can create mini-maps:

- Smoking history → lung cancer, COPD, CAD, PAD

- Obesity → OSA, diabetes, NAFLD, osteoarthritis

- Immobilization → DVT, PE, muscle atrophy

These maps help you connect symptoms with underlying disease patterns, a key downstream step in diagnostic thinking.

7. Phase-Specific Strategies: Premed vs Early Medical Student

The way you extract differential diagnosis lessons will vary depending on your training stage.

As a Premed

Your goals:

- Recognize that medicine is structured, not just “doctor intuition”

- Learn to think in symptoms, not just final diagnoses

- Show schools you understand clinical reasoning as a process

Tactics:

- Focus heavily on chief complaint → major differential categories

- Build “top 3 diagnoses” lists for common symptoms

- Note how social history, family history, and risk factors shape the differential (“smoker with cough” vs “non-smoker with cough”)

- During interviews, discuss shadowing using reasoning language:

- “I began to notice that every time someone came in with chest pain, the physician’s first mental split was ‘cardiac vs non-cardiac’ and they used very specific questions to separate those pathways.”

This signals that you are not just an observer—you are already engaging with the cognitive side of medicine.

As an Early Medical Student (pre-clinical or early clinical)

Your goals:

- Practice constructing full differentials using standard frameworks (VINDICATE mnemonic, organ-system-based, symptom-based)

- Compare your reasoning to actual physician reasoning

- Start recognizing cognitive biases and errors

Tactics:

- Before the encounter ends, write your own quick differential in the margin. After the visit, compare to what the physician documented or explained.

- Use a structured approach:

- By system: cardiac vs pulmonary vs GI vs musculoskeletal for chest pain

- By acuity: emergent vs urgent vs chronic

- When appropriate, ask:

- “I had thought about X in my differential but you did not mention it—can you tell me why it was less likely here?”

This accelerates your transition from preclinical theory to real-world application.

8. Common Pitfalls That Destroy Diagnostic Learning During Shadowing

Several traps will ruin your ability to extract differential diagnosis lessons if you are not careful.

Trying to impress instead of to understand

You are not there to “show off” by naming obscure diagnoses. You are there to observe disciplined reasoning. Overreaching will make physicians less eager to teach.Over-focusing on rare “cool” cases

You will remember the one case of myasthenia gravis crisis or Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. That is fine. But you will be tested in training and practice far more on pneumonia, MI, UTI, osteoarthritis, depression. Build detailed differentials for common symptoms first.Confusing outcome with process

A wrong diagnosis that was revised later can be as educational as a correct one, often more so. Focus on:- What they initially prioritized

- How new data shifted the differential

- What mistake was avoided or caught

Ignoring “boring” parts of the visit

The follow-up questions, medication review, and risk factor discussion are where you see how comorbidities alter differential probability.Documenting too much or too little

Five pages of narrative is useless. So is one-word summaries. Use the structured case template—short, consistent, analyzable.

9. Ethical and Professional Boundaries While Learning Differentials

You must balance aggressive learning with uncompromising professionalism.

- Never write patient names or identifiers in your notes.

- Never discuss specific patients with friends or online, even in “de-identified” casual ways.

- Never suggest diagnoses to patients. You are not their clinician.

- If a patient asks, “What do you think I have?”, defer respectfully:

- “I am a student here to learn. Your doctor is the best person to answer that question.”

You are training a diagnostic mindset, not practicing medicine. Understand that distinction clearly.

FAQ (Exactly 5 Questions)

1. I am a premed with no clinical knowledge. How can I realistically think in differentials while shadowing?

Start at the level of symptom → 3–5 possible causes. You do not need perfect terminology. For “chest pain,” you might write: “heart problem, lung blood clot, reflux, muscle strain.” After shadowing, look each up and convert them to proper terms (MI, PE, GERD, costochondritis). Repeat this across common symptoms. Over time, patterns form even before formal medical school teaching.

2. Can I use my shadowing cases in medical school applications and interviews?

Yes, but frame them around what you learned about clinical reasoning and patient care, not as if you participated in diagnosis. For example: “Shadowing a family physician, I observed how he approached every case of shortness of breath with a structured checklist to rule out life-threatening causes before addressing chronic conditions. That shifted my understanding of how deliberate and systematic good medicine is.”

3. How many cases per shadowing session should I write up in detail?

Aim for 3–5 well-documented cases per half-day session. Trying to write up every patient will dilute your focus and become unmanageable. Choose a mix of one or two common high-yield complaints and one case that seemed particularly complex or educational.

4. What resources are best to connect my shadowing observations to formal differentials?

For early learners, “Symptom to Diagnosis” (Stern) is excellent. UpToDate and AMBOSS have symptom-based entries that map exactly onto what you see in clinic. Even basic review books (First Aid, Step 2 resources) can help you build emergent vs common vs rare lists for high-yield complaints like chest pain, abdominal pain, and headache.

5. Is it appropriate to ask physicians directly about their differential diagnosis after each patient?

Yes, if you are respectful of time and pick your moments. A good approach is: “When you have a minute later, I would love to hear how you thought through that patient’s shortness of breath—what diagnoses you were worrying about and how you ruled them out.” This signals genuine interest in reasoning, not second-guessing. Many clinicians enjoy explaining their thought process when asked thoughtfully.

Key takeaways:

- Treat every shadowed patient as a structured mini-case with a chief complaint, a working differential, and a reasoning pathway you can reconstruct later.

- Use a three-tier note system and weekly review to convert scattered encounters into durable, symptom-based differential templates.

- Ask targeted, reasoning-focused questions to expose how real clinicians distinguish life-threatening from benign and common from rare—long before you carry your own patient load.