Most premeds completely blur outpatient and inpatient shadowing into one vague “clinical exposure” box—and that is a mistake.

If you do not define different learning objectives for outpatient vs inpatient shadowing, you waste the unique advantages of each environment and look unsophisticated when you write or talk about your experiences.

Let me break this down specifically.

(See also: How to Build a Structured Shadowing Notebook for Clinical Reasoning for more details.)

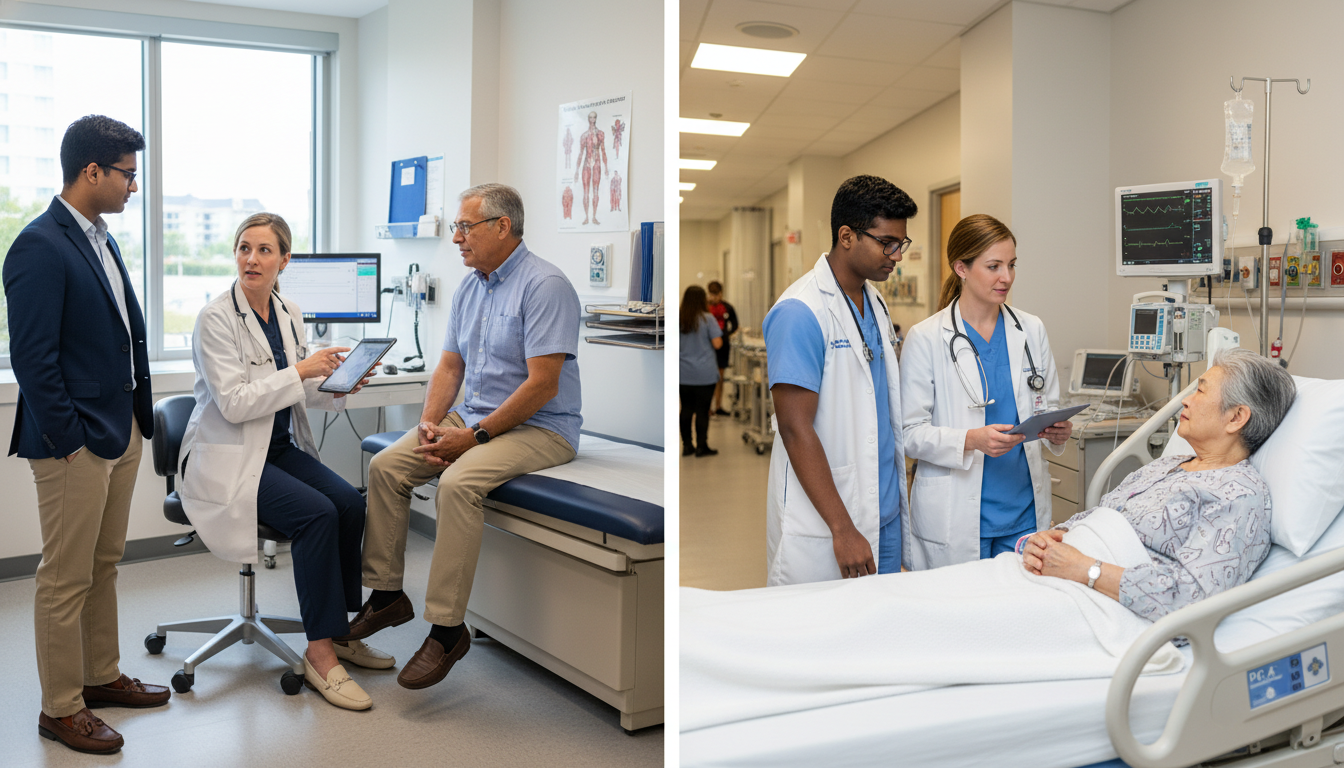

Outpatient vs Inpatient: You Are Observing Two Different Worlds

You are not just choosing where to shadow. You are choosing what kind of medicine you are learning to see.

Outpatient shadowing (clinic, office-based practice, ambulatory care) is fundamentally about:

- Longitudinal relationships

- Ambiguity management

- Time management and efficiency

- Preventive care and chronic disease control

Inpatient shadowing (wards, ICU, inpatient consults, ED boarding) is fundamentally about:

- Acute illness

- Triage and prioritization

- Team-based care

- Systems, handoffs, and risk

If your shadowing reflection reads the same for both settings—something like “I watched the doctor talk to patients and learned about empathy”—you are missing the point. Admissions committees can tell.

So you need distinct, concrete learning objectives for each setting.

Core Learning Objectives: Outpatient Shadowing

Outpatient medicine is where volume, variability, and continuity collide. Your job as a shadower is not to count the hours, but to extract patterns.

Here are specific, high-yield learning objectives that actually show maturation when you write secondaries or prepare for interviews.

1. Understand the Structure and Flow of an Outpatient Visit

Objective: Be able to describe the typical anatomy of a 15–20 minute office visit, from the moment the patient is called from the waiting room to the moment the after-visit summary prints.

What to actually watch for:

- How MA/nurse intake sets up the visit

- Vital signs, chief complaint, medication reconciliation

- Where the physician re-verifies vs trusts the intake

- Physician’s mental “script” for common visits

- Annual physical vs chronic disease follow-up vs acute complaint

- How they front-load, sequence, and time-box issues (“We have time for two main concerns today—let’s prioritize.”)

- How documentation is woven into the visit

- Typing during the visit vs after

- Use of templates, smart phrases, problem lists

Deliverable you should be able to verbalize:

“On a typical follow-up visit for diabetes and hypertension, I noticed Dr. X consistently opened with a 1–2 minute agenda setting, then targeted 8–10 minutes on the top two issues, leaving 3–5 minutes for education and closing the loop.”

This level of specificity shows you actually watched with intention.

2. Observe Longitudinal Care and Chronic Disease Management

Objective: See how chronic illnesses are managed over months to years, not just during crises.

Target conditions to track across multiple patients:

- Type 2 diabetes

- Hypertension

- Coronary artery disease

- COPD/asthma

- Depression/anxiety

What to look for:

- How the physician assesses control vs exacerbation (e.g., A1c trends, home blood pressures, symptom diaries)

- Incremental medication changes vs major regimen overhauls

- Lifestyle counseling realism

- How often advice is repeated

- How the physician handles nonadherence without shaming

- Use of guidelines vs individualized care

- “The guideline says X, but for you I will do Y because…”

If you shadow regularly in the same clinic, you can see the same patient more than once. That is gold. Note:

- How the relationship tone changes over visits

- Whether the patient trusts the plan more over time

- How setbacks are reframed (“We overshot the insulin dose; let’s adjust.”)

3. Learn Patient Communication in Time-Constrained Settings

Objective: Identify specific communication micro-skills clinicians use to communicate efficiently without seeming rushed.

Watch for:

- How they enter the room (knock, greet, sit vs stand)

- Open-ended vs closed questions and when each is used

- How they interrupt—because they will—without alienating the patient

- “Let me pause you there to make sure I am understanding…”

- How they deliver “bad” but non-catastrophic news (e.g., “Your blood pressure is still above goal.”)

- Handling of emotion in outpatient settings:

- When a patient gets frustrated, blames the system, or expresses financial barriers

- Physician strategies: validation, normalizing, reframing, problem-solving

Concrete learning goal: Walk away with at least 5 exact phrases or techniques you observed that you might want to emulate some day.

Examples:

- “On a scale of 0–10, how confident do you feel that you can actually do this plan this week?”

- “I hear that you are overwhelmed; let’s pick just one change to focus on.”

4. See How Physicians Manage Clinical Uncertainty and “Mild” Symptoms

Outpatient medicine is filled with vague symptoms: fatigue, chest discomfort that is “not really pain,” headaches that are “not the worst of my life but annoying.”

Objective: Understand the physician’s approach to risk stratification when patients are not obviously sick.

Watch carefully:

- How the physician uses history and physical to separate:

- Red-flag features → urgent workup or ED referral

- Benign features → reassurance and watchful waiting

- How they explain uncertainty without panicking the patient:

- “I do not see any signs of X today, but I want you to watch for A, B, C and call me if they appear.”

- How they document safety-net instructions in the note and the after-visit summary

Admissions committees like applicants who recognize that medicine is not always diagnostic clarity; outpatient is where you see “gray zones” constantly.

5. Observe Interprofessional Collaboration and Clinic Operations

Objective: Map the invisible system that makes a clinic run.

Things to notice:

- Who actually does what:

- MAs vs RNs vs APPs vs front-desk staff

- Who gives vaccines, who calls back labs, who refills medications

- How messages flow:

- EMR inboxes, voicemail, portal messages

- The physician’s strategy not to drown in MyChart (or equivalent) messages

- Practical realities:

- No-show rates

- Double-booking

- “Work-in” same-day visits

Concrete output: Be able to describe at least one systems-level frustration you saw (e.g., insurance prior auth delay) and how the team navigated it.

This shows you understand medicine as a system, not just “doctor and patient in a room.”

Core Learning Objectives: Inpatient Shadowing

Inpatient care is different. The rhythms, stakes, and team dynamics are more intense. Your role as a shadower changes, and so should your learning objectives.

1. Understand the Daily Flow of Inpatient Medicine

Objective: Be able to outline a typical inpatient day for a ward team or hospitalist.

Pay attention to:

- Pre-rounding vs rounding:

- When the residents/attendings see patients alone, review overnight events, labs, imaging

- Timing of formal bedside rounds

- Geographic vs non-geographic rounding (all patients on one unit vs scattered)

- Structured presentations:

- SOAP format

- One-liner case summaries

- “Overnight events, subjective, objective, assessment, plan” rhythm

- The discharge process:

- Criteria for discharge readiness

- Medication reconciliation

- Discharge summary and instructions

By the end, you should be able to say something more sophisticated than “The doctors checked on all their patients.” For instance: “I noticed that the intern used a structured one-liner and prioritized unstable patients first, then stable, with discharge-ready patients seen near the end of rounds to finalize plans.”

2. See Acute Illness and Decompensation in Real Time

Outpatient is often about “not that sick yet.” Inpatient is the other side.

Objective: Learn to distinguish patients who are acutely ill, unstable, or improving—based on what you can observe as a novice.

Focus on:

- Vital sign trajectories:

- New O2 requirement

- Hypotension, tachycardia

- Fever curve patterns

- Level of monitoring:

- Floor vs step-down vs ICU

- Telemetry monitoring vs no telemetry

- Visual cues:

- Work of breathing

- Level of consciousness

- Lines and tubes (IVs, catheters, central lines, ventilators)

You are not diagnosing, but you are building pattern recognition. A powerful learning objective: “Develop a basic sense for what ‘sick’ looks like in the hospital and how the team reacts when a patient worsens.”

Watch:

- Rapid response or code situations from an appropriate distance

- How the team communicates in urgency vs routine

- Who takes leadership (often the senior resident or attending)

3. Study Team-based Care and Hierarchy

Inpatient medicine is a team sport with clear hierarchy.

Objective: Understand roles and communication patterns among:

- Attending physician

- Senior resident

- Interns

- Medical students

- Nurses

- Consultants

- Case managers, social workers, pharmacists, PT/OT

As you shadow:

- Observe who speaks first on rounds and who finalizes decisions

- Watch how nurses contribute critical information (e.g., overnight changes not in the EMR yet)

- Notice differences between how the attending teaches vs how the senior resident teaches

- See how consults are requested and integrated:

- “We will consult cardiology for X; our specific question is Y.”

Explicitly aim to be able to answer:

- “What does an intern actually do all day compared to the attending?”

- “How do nurses and physicians collaborate—or conflict—on plans?”

You will sound far more credible in an interview than someone who says, “There was a team seeing patients together.”

4. Observe Clinical Decision-Making Under Pressure

Objective: See how inpatient clinicians prioritize problems and make trade-offs in sicker patients.

Key patterns to track:

- Problem list management:

- “Acute on chronic heart failure” vs “Type 2 diabetes” vs “Fall at home”

- How they decide what matters today vs what can wait

- Risks of hospitalization:

- Delirium

- DVT/PE

- Nosocomial infections

- “Less is more” decisions:

- Stopping non-essential meds

- Avoiding unnecessary imaging or tests

Listen at the end of each patient’s discussion on rounds:

- How is the team summarizing the primary problem, active comorbidities, and disposition plan?

- What is the explicit goal of hospitalization today? (e.g., “We are trying to get him off oxygen,” “We are titrating diuretics,” “We are transitioning to oral antibiotics.”)

In your notes, try to capture one example where the team exercised restraint:

- Not ordering an MRI

- Choosing comfort-focused care

- Declining to pursue an invasive procedure in a frail patient

This shows you understand that good medicine is not just “doing more.”

5. Learn About Discharge Planning and Systems of Care

An underrated inpatient learning objective: discharge is often the hardest part.

Objective: Understand how hospital teams transition patients safely out of the hospital.

Watch for:

- Criteria used to determine discharge readiness:

- Clinical stability

- Ability to take PO meds

- Safe mobility or support at home

- Social determinants:

- Housing stability

- Caregivers

- Insurance and medication costs

- Coordination:

- Follow-up appointments scheduled before discharge

- Handoff to primary care or SNF

- Readmission prevention:

- Clear instructions on warning signs

- Med changes explained to patient and family

If you can articulate one complex discharge case—for example, an elderly patient with heart failure and no reliable caregiver—you instantly demonstrate awareness of the real-world constraints physicians face.

Comparing Learning Objectives: Outpatient vs Inpatient

You will impress admissions committees if you can say, concretely, what you could only have learned in each setting.

Clinical Content Focus

Outpatient

- Chronic disease management trajectories

- Prevention and screening

- “Gray zone” symptoms; risk without clear triggers

- Ambulatory procedures (skin biopsies, joint injections, Pap smears)

Inpatient

- Acute decompensation and rescue

- Complex multi-morbidity management during crises

- High-intensity procedures and interventions (central lines, chest tubes—but often observed only at a distance)

- End-of-life decision-making in real time

Communication and Relationship Dynamics

Outpatient:

- Long-term rapport; seeing patient’s life context

- Repeated conversations about lifestyle, adherence, and motivation

- Time pressure with many brief visits

Inpatient:

- Shorter, high-stakes relationships

- Breaking bad news about serious diagnoses

- Navigating family meetings and surrogate decision-makers

Systems and Workflow

Outpatient:

- Scheduling, no-shows, clinic throughput

- Insurance, authorization headaches, and medication access

- Asynchronous communication via phone/portal

Inpatient:

- Hand-offs between day and night teams

- Interdisciplinary rounds (case management, pharmacy)

- Discharge bottlenecks, bed management, and readmission risk

When you later write about shadowing, make the contrast explicit:

- “In clinic, I saw how Dr. A fought for patients’ medication coverage over weeks; on the wards, I saw Dr. B focus on getting patients stable enough that those outpatient struggles could resume safely at home.”

That is sophisticated reflection.

How to Set Personal Learning Objectives Before Each Shadowing Block

Most premeds show up to shadow passively. Do not do that.

For each new setting, define 3–5 specific, observable learning objectives. Here is how to formulate them.

Step 1: Match Objectives to Setting

Example objectives for outpatient day:

- Map the steps of a typical new patient visit and time spent on each.

- Identify three ways the physician builds rapport quickly with unfamiliar patients.

- Observe at least two examples of shared decision-making for screening or preventive care.

- Notice one systems-level barrier (e.g., insurance, transportation) and how the team responds.

Example objectives for inpatient day:

- Outline the structure of bedside rounds, including who speaks and in what order.

- Observe how the team prioritizes which patients are seen first and why.

- Identify at least one case where the team chooses not to do a possible intervention and explains their reasoning.

- Track the progression of one patient’s plan from admission toward discharge.

Step 2: Use These Objectives in Real Time

During shadowing:

- Keep a very small, discreet notepad (or notes app if allowed).

- Jot down:

- Key phrases

- Flow structures

- Interesting decisions

Do not take notes in patient rooms unless your host explicitly says it is acceptable. Step into hallway, then write.

Step 3: Reflect With Structure Afterward

Within 24 hours, write a brief reflection anchored to your objectives:

- What did you actually observe for each objective?

- What surprised you?

- What questions did it raise?

For applications, these reflections give you:

- Specific stories for “Describe a clinical experience” questions

- Concrete evidence you understand both sides of care: ambulatory and inpatient

How Medical Schools Interpret Your Outpatient vs Inpatient Experience

Committee members read hundreds of essays that say nothing more precise than “I liked interacting with patients.” You can stand out.

They will ask themselves:

- Does this applicant understand that primary care in clinic is different from subspecialty or hospital care?

- Have they seen the system of medicine, not just a doctor in isolation?

- Do they grasp that chronic disease management is long and messy?

Your distinct learning objectives signal:

- Maturity

- Insight into actual physician work

- Capacity to learn from observation, not just participation

Balanced exposure is helpful:

- Heavy outpatient only → you may underappreciate acuity and team dynamics

- Heavy inpatient only → you may romanticize crisis care and underestimate preventive work

If you must choose due to limited time, at least understand what you are not seeing, and acknowledge that in your reflections.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How many hours of outpatient vs inpatient shadowing should I aim for?

There is no magic number, but a balanced portfolio often looks like:

- 20–40 hours outpatient (primary care, maybe one subspecialty clinic)

- 20–40 hours inpatient (wards, ICU, or hospitalist service)

Quality and reflection matter more than totals. One deeply observed 4-hour ward round where you track three patients carefully can be more educational than 20 hours of aimless hallway following.

2. Is outpatient or inpatient shadowing more “impressive” for applications?

Neither is intrinsically more impressive. What matters is:

- Can you articulate what you learned that is unique to that setting?

- Can you describe patients, systems, and physician roles with specificity?

Some schools appreciate clear exposure to primary care; others care more that you have seen sick inpatients. Balanced exposure, or at least a thoughtful explanation for any imbalance, is ideal.

3. How do I talk about shadowing in secondaries and interviews without breaking confidentiality?

Strip out identifiers and focus on patterns, not unique personal details. For example:

- “I observed an elderly patient with advanced heart failure struggling to take medications correctly…” is fine.

- Avoid names, specific ages, rare conditions, and precise admission dates.

Emphasize your learning objectives and takeaways, not the patient’s biography.

4. I felt useless standing in the corner. How can I still get something meaningful from shadowing?

Feeling useless is normal. Shadowing is fundamentally observational. To make it meaningful:

- Arrive with clear objectives (e.g., “Today I am going to track how the doctor opens and closes each visit.”)

- Debrief briefly with the physician or resident if time permits: “I noticed you did X—can I ask why?”

Your role is not to contribute clinically; it is to learn to see the work behind each interaction.

5. Should I prioritize shadowing in the specialty I think I want, or focus on primary care and general inpatient?

Before medical school, breadth usually beats depth. Strong options:

- Outpatient: family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics

- Inpatient: general medicine wards, hospitalist teams, maybe ICU rounds

If you have a specific interest (e.g., cardiology), a small amount of specialty shadowing is fine, but ensure you also see generalist care. Your learning objectives should include understanding how generalists coordinate with specialists, which is central in both outpatient and inpatient practice.

Key points, distilled:

- Outpatient and inpatient shadowing are not interchangeable; each demands its own targeted learning objectives, from visit flow and chronic care to team dynamics and acute decision-making.

- The value of shadowing hinges on what you consciously observe and later articulate—specific workflows, communication strategies, and systems issues, not vague “exposure.”

- Applicants who can contrast what they learned in clinic vs hospital settings demonstrate real insight into how modern medicine is actually practiced, which is exactly what admissions committees are trying to detect.