observing monitors and drips Medical student [shadowing in an ICU](https://residencyadvisor.com/resources/shadowing-experience/shadowing-in-the-operating-](https://cdn.residencyadvisor.com/images/articles_v3/v3_MEDICAL_SHADOWING_EXPERIENCE_shadowing_in_the_icu_key_monitors_lines_and_drips_-step1-medical-student-shadowing-in-an-icu-http-8462.png)

Most premeds walk into the ICU and see chaos. The reality is colder: it is not chaos—it is a highly structured language. You just have not learned to read it yet.

Let me break this down very specifically.

If you are shadowing in an ICU, three things will define whether you look lost or quietly competent:

(See also: How to Build a Structured Shadowing Notebook for Clinical Reasoning for more details.)

- Whether you can glance at the monitors and know what matters.

- Whether you can look at the lines and tubes and identify what is going where and why.

- Whether you can recognize common drips (infusions) and their implications for how sick the patient really is.

You are not there to manage care. You are not there to touch anything. But you are there to learn, and that means decoding the environment so you can ask sharp questions and understand the team’s decisions.

ICU Shadowing Mindset: What You Should Actually Be Focusing On

When you first step into an ICU room, do not fixate on the ventilator settings or exotic drugs. Start with four questions:

- How is this patient being monitored?

- How are they being supported? (oxygen, pressors, sedation, nutrition)

- How are medications and fluids getting into the body?

- What is the “big picture” story of why the patient is here?

From the vantage point of a premed or early medical student, your job is pattern recognition, not management. You want to leave able to say something like:

“Room 12 is a 65-year-old with septic shock on norepinephrine via central line, on a ventilator with an arterial line for continuous blood pressure monitoring, plus Foley and NG tube.”

If you can get to that level of concise description, you are well ahead of most shadowers.

Let us start with the monitor, then move outward to lines and drips.

Reading the ICU Monitor: The Basics You Must Recognize

Every ICU room has a physiologic monitor. It tends to display multiple waveforms and numeric values. You do not need to interpret every detail. You do need to know what each major thing represents.

1. Core Parameters on the ICU Monitor

Typical main screen values:

- ECG / Heart Rate (HR)

- Blood Pressure (BP) – noninvasive cuff and/or arterial line

- Oxygen Saturation (SpO₂)

- Respiratory Rate (RR)

- Temperature

- Sometimes: Central Venous Pressure (CVP) or other pressures

Let us break them down practically.

ECG and Heart Rate

- Usually a green waveform at the top.

- HR displayed as a number (e.g., 88) often near the top in green.

- Rhythm strips: You might hear terms like “sinus rhythm,” “AFib,” “VT.”

What you should notice:

- Is the HR very high (>120) or very low (<50)?

- Is the monitor alarming for arrhythmias?

- If the team suddenly rushes in because of a “run of VT,” you want to know this refers to ventricular tachycardia—an unstable, potentially lethal rhythm.

This matters because high-dose drips (like vasopressors) can sometimes worsen arrhythmias.

Blood Pressure: Cuff vs Arterial Line

Two ways BP shows up:

Noninvasive Blood Pressure (NIBP)

- Cuff on the arm.

- Displays numbers like 120/70 (85), where the last number is MAP (mean arterial pressure).

- Cycles intermittently (every few minutes).

Arterial Line (Art line)

- Invasive catheter, commonly in radial artery.

- Displays a continuous arterial waveform.

- Usually marked as “ART” or “A-line” with values like 92/54 (67).

In the ICU, MAP is king. Typical goal in shock: MAP ≥ 65 mmHg.

As a shadower, notice:

- Does the patient have an arterial line?

- Are nurses adjusting pressors (like norepinephrine) to target a MAP ≥ 65?

When someone says “pressors up, MAP’s dropping,” you know they are fighting hypotension.

Oxygen Saturation (SpO₂)

- Displayed as a percentage, often in blue or another distinct color.

- Based on pulse oximetry (finger/ear probe).

- Normal: about 94–100% in a healthy lung; ICU patients may be acceptable lower depending on disease (e.g., ARDS might target 88–92%).

Key point when shadowing:

- If SpO₂ is persistently <90%, everyone cares.

- Alarms for “low sats” will trigger rapid assessment of the airway, breathing, ventilator, and oxygen delivery.

Tie this mentally to the oxygen devices: nasal cannula, non-rebreather mask, high-flow, or ventilator.

Respiratory Rate (RR)

- Listed as a number, may also have a waveform from chest impedance.

- Normal: roughly 12–20 breaths per minute, but ICU norms vary with illness and ventilator settings.

Note:

- High RR (e.g., >30) may signal distress, sepsis, acidosis, anxiety.

- On a ventilator, the “set” rate might differ from the “actual” rate. Patients can breathe over the vent.

Temperature

- May be continuous via bladder/central line probe, or intermittent.

- Fevers and hypothermia both matter for sepsis, shock, and neurologic injury.

You do not need to diagnose, just recognize that a core temp of 39.5°C in a septic patient explains why they are on broad-spectrum antibiotics and fluids.

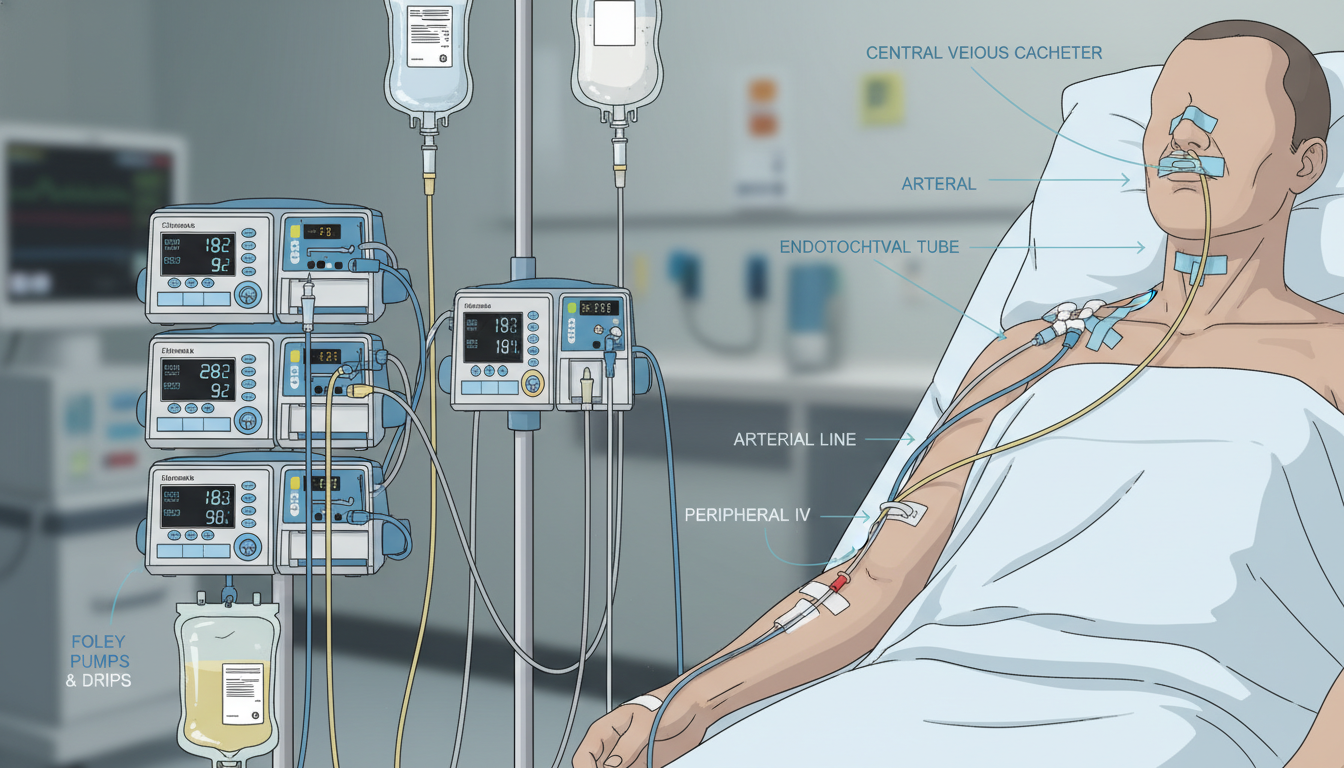

Lines and Tubes: Mapping the Hardware on the Patient

When you look at an ICU patient, you are really looking at a network: entry points, exit points, and monitoring points. Identify these and you understand the patient’s life support.

1. Vascular Access: How Meds and Fluids Enter

Peripheral IV Lines

- Location: Hand, forearm, antecubital fossa.

- Secured with transparent dressing.

- Often used for:

- Maintenance fluids

- Antibiotics

- Lower-risk medications

As a shadower, you might hear “just peripheral access, no central line yet.” That means they are less invasive for now, or central access is pending.

Central Venous Catheters (Central Lines)

These are critical in the ICU. Common sites:

- Internal jugular vein (neck)

- Subclavian vein (under clavicle)

- Femoral vein (groin)

They usually have multiple lumens (2–3 ports) and are used for:

- Vasopressors (norepinephrine, vasopressin, etc.)

- High-osmolarity meds (e.g., some chemo, high-concentration electrolytes)

- Rapid fluids

- Central venous pressure monitoring (sometimes)

When shadowing, central line presence is a red flag for “this patient is sick enough to need strong medications that are unsafe for peripheral IVs.”

You might hear:

- “Triple-lumen IJ central line”

- “We need a central line before starting vasopressors”

Recognize that vasopressors through a peripheral IV risk severe tissue injury if the IV infiltrates.

Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters (PICCs)

- Inserted in upper arm → tip ends in central circulation.

- Used for:

- Longer-term antibiotics

- TPN (total parenteral nutrition)

- Intermittent access in chronically ill patients

They are central, but placed by specialized nurses or interventional radiology rather than emergently by intensivists at bedside in most cases.

Arterial Lines (Art Lines)

- Not for giving medications.

- Used for:

- Continuous blood pressure monitoring

- Frequent arterial blood gases (ABGs)

Common sites:

- Radial artery (wrist) – most common

- Femoral artery (groin)

Identify them by:

- Stiff tubing connected to continuously flushing pressure bag.

- Arterial waveform on monitor.

- Label like “ART” or “A-line” on the screen.

2. Airway and Breathing: Tubes and Support

Recognizing respiratory support devices quickly helps you gauge acuity even before looking at the chart.

Endotracheal Tube (ETT)

- Clear tube exiting mouth, secured with devices or tape.

- Connects to ventilator tubing.

- Used when the patient is mechanically ventilated.

If you see an ETT and vent tubing: the patient is intubated. This almost always means a high-acuity patient (respiratory failure, shock, post-op, neurologic compromise).

Tracheostomy Tube

- Enters through neck into trachea.

- Common in:

- Prolonged ventilation

- Certain head/neck pathologies

- Difficult airway cases

Functionally similar to an ETT but surgically placed. For shadowing, notice that some trach patients may be awake, communicating with speaking valves, or weaning off the ventilator.

Noninvasive Support: Masks and Cannulas

You will see:

- Nasal Cannula (NC) – low-flow oxygen.

- High-Flow Nasal Cannula (HFNC) – thicker tubing, delivers higher flows and precise FiO₂.

- Non-rebreather Mask (NRB) – mask with reservoir bag.

- BiPAP/CPAP Masks – tight face masks delivering positive pressure without an ETT.

BiPAP/CPAP in the ICU often indicates a patient at risk of needing intubation if they worsen.

3. GI Tubes: Feeding, Decompression, Medication Delivery

Nasogastric (NG) or Orogastric (OG) Tubes

- Enter via nose (NG) or mouth (OG) into stomach.

- Functions:

- Remove gastric contents (decompression)

- Deliver enteral nutrition

- Deliver medications

You might see tube feeds connected via a pump, or tube to gravity / wall suction in bowel obstruction or post-op patients.

PEG / G-tubes

- Percutaneous tubes placed directly into the stomach or jejunum.

- Used in long-term feeding when oral intake is not possible.

4. Urinary and Other Drains

Foley Catheter

- Tube from urethra to urine drainage bag.

- Allows hourly urine output measurement, which is critical in shock and kidney injury.

As a shadower, track occasional nurse updates like “urine output is dropping” — this often signals worsening perfusion or renal function.

Surgical Drains, Chest Tubes

You might encounter:

- Chest tubes – drain air or fluid from pleural space (e.g., pneumothorax, hemothorax).

- JP (Jackson-Pratt) drains – bulb suction drains near surgical sites.

- EVD (External Ventricular Drain) – neurosurgical patients, drains CSF, monitors intracranial pressure.

You do not need to master them, but at least recognize:

- A large tube exiting the chest connected to a collection canister = chest tube.

- Clear tube from scalp to a graduated chamber at specific height = EVD.

Drips and Infusions: Reading the Pump Tower

The “pump tower” in the ICU is one of the most intimidating features: multiple infusion pumps stacked vertically, each with tiny screens and labels. Learning the big players transforms this from noise into meaningful information.

How to Visually Scan the Pumps

When you look at the pumps:

- Identify whether there are many active drips (6–10) or only a couple. More usually means sicker.

- Look (from a distance) at the labels: pressors, sedatives, analgesics, insulin, antibiotics, etc.

- Ask yourself: Are these life-support drips or supportive/comfort drips?

Life-support drips are things like vasopressors and inotropes. These mean the patient cannot maintain blood pressure or perfusion without them.

1. Vasopressors: The “Pressors”

These are central in critical care. When a patient is in shock, pressors are used to maintain MAP ≥ 65.

Most common:

Norepinephrine (Levophed)

- First-line pressor for septic shock in most ICUs.

- Potent vasoconstrictor, modest beta-agonist.

- Often hung via central line.

- You might hear: “Levo at 0.1 mcg/kg/min, titrating to MAP 65.”

Vasopressin

- Often added to norepinephrine in refractory septic shock.

- Fixed dose in many protocols (e.g., 0.03 units/min).

Epinephrine

- Used in some shock states or post-arrest care.

- Strong beta and alpha agonist; more arrhythmogenic.

Phenylephrine (Neo)

- Pure alpha agonist.

- Sometimes used when tachycardia is problematic.

Dopamine (much less favored nowadays in many ICUs due to arrhythmia risk).

For shadowing purposes:

- Multiple vasopressors = more severe shock.

- If someone says “on maxed-out pressors,” they mean doses are very high and shock is critical.

2. Inotropes: Pump Support

- Dobutamine

- Increases cardiac contractility.

- Used in cardiogenic shock, low cardiac output states.

- Milrinone

- Inotrope and vasodilator.

- Often in heart failure patients, sometimes bridging to advanced therapies.

Pressors squeeze vessels. Inotropes squeeze the heart. Patients on inotropes usually have pump failure (heart not ejecting well).

3. Sedation and Analgesia Drips

Intubated patients often need:

- Propofol

- Sedative, milky white infusion.

- Rapid onset/offset; used for continuous sedation.

- Can cause hypotension, so interplay with pressors is critical.

- Midazolam (Versed)

- Benzodiazepine sedative; longer acting.

- Dexmedetomidine (Precedex)

- Sedative with some analgesic and anxiolytic properties.

- Less respiratory depression; used in weaning and for cooperative sedation.

- Fentanyl

- Potent opioid analgesic.

- Often as a continuous drip in ventilated patients.

While shadowing, watch for patterns:

- Propofol and fentanyl together → deeper sedation, common in early mechanical ventilation.

- Precedex → often for lighter sedation, especially when trying to wean or extubate.

If you see “sedation vacation” written on the board or hear the term, that refers to temporarily stopping sedatives to assess neurologic status and ventilator readiness.

4. Insulin and Other Critical Drips

Common ICU continuous infusions:

- Insulin drips

- Used for tight glucose control in DKA, hyperglycemic crises, or severe illness.

- Heparin drips

- Anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation, DVT/PE, mechanical valves, etc.

- Antiarrhythmic drips

- E.g., amiodarone for ventricular arrhythmias.

You may also see antibiotics run as extended (or continuous) infusions in some ICUs (like piperacillin-tazobactam, meropenem), but many are intermittent.

Putting It Together: How to “Read” an ICU Patient in 60 Seconds

As a shadower, you can impress without pretending to know more than you do. The trick is structured observation.

When you enter the room:

Start with the patient’s connection to life support

- Intubated or not?

- On noninvasive support (BiPAP / HFNC) or just nasal cannula?

- Are they awake, following commands, sedated, or paralyzed?

Scan the monitor

- HR: tachycardic, bradycardic, or normal?

- BP/MAP: are they meeting goals (>65 MAP?), any arterial line?

- SpO₂: Are the sats reassuring (>92) or marginal (low 90s or 80s)?

- RR: tachypneic or controlled on vent?

Map the lines

- Peripheral IVs only vs clear central line in neck/chest/groin.

- Arterial line present?

- Foley catheter in place?

- Feeding tube (NG / OG / PEG)?

Read the pump tower

- Look (from a safe distance) at labels:

- Norepinephrine / vasopressin / epinephrine → shock.

- Propofol / fentanyl / Precedex → sedation/analgesia.

- Insulin → glucose control.

- Heparin → anticoagulation.

- Many high-level drips generally = higher acuity.

- Look (from a safe distance) at labels:

Synthesize one sentence in your head

- “This is an intubated septic shock patient on norepinephrine and vasopressin via central line, with an arterial line for close BP monitoring, sedated on propofol and fentanyl.”

You do not say this out loud unprompted. But when the attending turns and asks, “What do you notice about this patient’s support?”, you are not left staring at the ventilator.

Shadowing Etiquette in the ICU: Staying Safe and Useful

Knowing the hardware is only half the task. ICU is high-risk space. A few very specific rules matter.

1. The “Do Not Touch” Rule

You should never:

- Adjust IV pumps

- Silence or change monitor alarms

- Change oxygen flow or ventilator settings

- Manipulate lines, tubes, or dressings

If an alarm sounds, you notify the nurse or resident. That is it.

2. Where to Stand

Try to position yourself:

- Not between staff and the head of the bed (airway access).

- Not between staff and the IV pump tower.

- Toward the periphery, with clear exit routes.

If resuscitation begins (code situation):

- Move out of the room or to a far corner unless invited to stay.

- This is not your time to “get close”; it is their time to save a life.

3. How to Ask Smart Questions

Questions that play well in ICU shadowing:

- “I see there is a central line and an arterial line. What made you decide to place both in this patient?”

- “This patient is on norepinephrine and vasopressin. How do those two drugs differ in what they do?”

- “I noticed the MAP goal is 65. Why that number specifically?”

- “How do you balance sedating the patient for comfort with trying to wean them from the ventilator?”

Avoid:

- Asking questions during acute emergencies.

- Asking “What does that do?” about every single line—try to group your questions after observation.

4. Emotional Reality

Not every ICU story ends well. As a premed or early trainee, you might see:

- Family meetings about goals of care.

- Withdrawal of life support.

- Prolonged suffering.

If you feel overwhelmed, quietly mention it to your supervising physician or a resident after leaving the room. Emotional processing is part of ICU training, and acknowledging it early is a sign of maturity, not weakness.

Simple Pre-Shadowing Prep That Pays Off

Before your ICU shadow day, reviewing a few targeted topics will dramatically increase how much you absorb.

Focus on:

- Basic hemodynamics: HR, BP, MAP, SpO₂, RR.

- Common shock types: septic, cardiogenic, hypovolemic, obstructive (just conceptually).

- Names and broad categories of key drips:

- Norepinephrine → pressor.

- Dobutamine → inotrope.

- Propofol → sedative.

- Fentanyl → analgesic.

- Lines vocabulary:

- Peripheral IV vs central line vs PICC vs arterial line.

- Foley catheter vs condom catheter.

- NG/OG tube vs PEG tube.

That level of prep is enough. You do not need to know every receptor or advanced ventilator mode.

FAQs

1. As a premed, is it appropriate to ask what each line is while in the patient’s room?

Briefly, yes, but with restraint. If the team is calm and doing routine care, a quiet question such as “Is that a central line or an arterial line?” is acceptable. If the room is busy or the patient is unstable, hold your questions until you step out. You can also ask for a “walkthrough” of the lines on a whiteboard rather than over an actual patient.

2. How can I tell if a patient is really “critical” versus just monitored in the ICU?

Look for patterns: intubation, central line plus arterial line, multiple vasopressor drips, continuous sedation, and hourly urine outputs are all indicators of high acuity. A patient in a step-down or lower-acuity ICU bed might have just oxygen by nasal cannula, a single peripheral IV, and no pressors.

3. Should I try to read the ventilator settings during shadowing?

You can certainly look, but as a premed or early student, your time is better spent recognizing that a patient is intubated and how that correlates with their monitor and drips. Ventilator modes and settings are more advanced; if you are curious, ask the resident or RT to explain one or two key settings rather than trying to understand everything.

4. What is the best way to document or remember what I learn during ICU shadowing?

Right after your shift, jot down brief notes: one or two cases that stood out, lines and drips you saw, and a couple of questions that arose. Do not include identifying details (no names, dates of birth, or room numbers). Frame each case in broad strokes: age range, main diagnosis, main supports (e.g., “intubated septic shock on norepinephrine via central line”). These notes help solidify your mental models without violating privacy.

5. Will understanding ICU monitors and drips actually help me with med school applications or interviews?

Yes, indirectly. When you discuss your shadowing, you can move beyond “I saw really sick patients” and instead say, for example, “I saw how decisions about starting norepinephrine via central line, monitoring MAP with an arterial line, and adjusting sedation on the ventilator all fit together in managing septic shock.” That level of specificity signals genuine engagement with the clinical environment rather than superficial observation.

Key takeaways:

- The ICU is not random chaos; it is a structured language of monitors, lines, and drips that you can begin decoding even as a premed.

- Focus your shadowing on pattern recognition—oxygen support, key monitors, vascular access, and life-support infusions—rather than trying to manage care.

- Respect the environment: observe from the periphery, never touch equipment, and use thoughtful, well-timed questions to turn a high-tech, intimidating space into a powerful learning experience.