The usual behavioral interview advice will fail you if you barely have clinical experience. You need different tactics.

If you’re applying to residency with thin clinical exposure—late career switch, heavy research background, long preclinical leave, IMG with limited USCE—you cannot walk into interviews using the same playbook as your classmates who lived in the hospital. You’ll get exposed as soon as someone says, “Tell me about a time you handled a difficult patient.”

Here’s how you handle it without lying, panicking, or sounding like an underqualified spectator.

1. Face Your Reality: You’re Competing on Story Quality, Not Setting

Stop comparing your experiences to the person who scribed for 4 years and did 5 away rotations. You can’t win that game.

But behavioral interviews are not strictly about medicine. They’re about patterns of behavior: how you think, how you react, how you recover, and how you work with others.

Programs are trying to answer:

- Will you be safe and coachable on day one?

- Do you handle stress without melting down or becoming toxic?

- Can you function on a team at 3 a.m. when everyone is tired?

- When you screw something up (you will), do you own it or hide it?

You can demonstrate all of that without 500 hours of inpatient experience. But you must be deliberate. Passive “let me just see what they ask and wing it” is how people with limited exposure sink their own chances.

Step one: accept this constraint and build a strategy around it.

2. Build a Story Inventory That Does Not Depend on Clinical Volume

You need a bank of 12–15 stories ready to go. Not memorized scripts—situations you know well enough to flex into different questions.

And no, they don’t all have to be from the hospital.

Good sources for behavioral stories if your clinical bench is shallow:

- Research labs (conflicts, failed experiments, deadlines, authorship issues)

- Work before medicine (IT, finance, teaching, military, retail, etc.)

- Volunteer roles (crisis hotlines, shelters, community health fairs)

- Leadership (clubs, organizations, coaching, teaching assistant)

- Family and life events (caregiving, immigration, major setbacks—used carefully and sparingly)

- Limited but real clinical moments (that one ICU patient you followed closely counts if you actually did something more than observe)

You want repeated themes: conflict, failure, ethical tension, teamwork, feedback, time pressure, ambiguity.

Here’s how to organize this quickly.

| Category | Example Source |

|---|---|

| Conflict | Lab authorship dispute |

| Teamwork | Group project leadership |

| Leadership | Club officer role |

| Failure | Low exam/Step score |

| Communication | Teaching or tutoring |

| Ethics | Data integrity issue |

Take one hour today and:

- List 6–8 “chapters” of your life that involved real stress or responsibility.

- For each, write 2–3 bullets:

- What went wrong / what was hard

- What you did

- What changed afterwards

That’s your raw material. We’ll shape it next.

3. Rewrite Your Stories In Residency Language (Even If They Aren’t Clinical)

Here’s where most “low-clinical” applicants blow it. They tell a good lab or corporate story but never connect it to residency.

The interviewer thinks: “Okay, nice, but can you survive nights on the wards?”

You have to translate. Explicitly.

Use a modified STAR framework, but with a twist:

- Situation – Context, but brief.

- Task – What you were responsible for.

- Action – What you actually did (this is where your value shows).

- Result – What happened.

- Reflection – How this translates to residency.

That last “R” is what saves non-clinical stories.

Example: You get, “Tell me about a time you managed a conflict on a team,” and your best story is from a research lab.

Weak version (what many people do):

- Long explanation of the project

- Blurry description of the conflict

- Vague “we talked and communicated and it got better”

Strong version (what you should do):

Situation:

“In my second year in the lab, we were on a tight timeline for a paper. Two grad students disagreed about which dataset should be primary, and the tension started to delay analysis.”

Task:

“As the only MD-track person on the project and the one handling much of the data cleaning, I was in the middle of both workflows and needed them aligned or we’d miss the deadline.”

Action:

“I scheduled a short, structured meeting—30 minutes—where each person would present their reasoning and what they needed. I set basic rules: no interruptions, time-limited points, focus on data and timeline. After they presented, I summarized both positions and tied them to the deadline. I suggested a compromise: we’d run the analysis both ways in parallel for 3 days, see if the conclusions actually changed, and commit in advance to the stronger, cleaner result. I took on the extra data work and sent daily updates.”

Result:

“We hit the deadline, the results were actually concordant, and both people felt heard rather than steamrolled. The PI later told me that meeting probably saved a month.”

Reflection (critical piece):

“For residency, I see similar dynamics on teams—different attendings, nurses, and residents may have different preferences. My default is to clarify the goal, surface everyone’s concerns, then move toward a data-driven or guideline-supported compromise that respects the timeline and patient safety first.”

Now your research story suddenly feels relevant to a team on medicine wards. That’s the whole game.

4. How To Handle Classic Clinical Behavioral Prompts Without Lying

Yes, you’ll still get direct clinical questions.

“Tell me about a difficult patient.”

“Describe a time you made a clinical mistake.”

“Tell me about a time you had to deliver bad news.”

If your experience is limited, you have three options:

- Use a real but small-scale clinical story and make the thought process the star.

- Pivot honestly to an adjacent situation (sim, hotline, non-medical but analogous) and explain the link.

- Combine limited clinical details with robust team/communication dynamics.

What you don’t do: invent ICU disasters or claim responsibilities you never had. Interviewers smell that a mile away.

Example: “Tell me about a difficult patient.”

You did one sub-I, barely any direct patient counseling. Fine.

You might say:

“I’ve had fewer longitudinal patient relationships compared to some applicants, but one encounter during my internal medicine sub-I really shaped how I think about ‘difficult’ patients…”

Then describe:

- A patient refusing meds or tests

- A personality clash

- A family member who distrusted the team

Keep it honest about your role:

“I was the medical student on the team, but I took responsibility for spending extra time at the bedside…”

Then show:

- How you listened

- How you adjusted your communication

- How you worked with nurses / social work / attending

- What changed, even if just slightly

If your most “difficult human” story is actually non-clinical—say, de-escalating an angry parent as a teacher—you can still use it. Just explicitly bridge back:

“Before medical school, I taught high school. Different setting, but the principles of de-escalation and aligning with someone’s goals are exactly what I’ve used with patients during my rotations.”

That connection line is mandatory. It prevents the interviewer from mentally dismissing the story as irrelevant.

5. Tactics To Compensate For Limited Clinical Exposure

Let me be blunt: programs will notice if your clinical resume is lighter. Your job in the interview is to:

- Show you understand the gap

- Demonstrate you’ve already started closing it

- Prove the way you learn and adapt is one of your biggest strengths

Here’s exactly how.

5.1 Own the Gap Before They Weaponize It

If someone says, “Tell me about your clinical experience,” do not pretend it’s something it’s not.

Better version:

“I recognize that compared to some applicants, my US clinical experience is narrower. That’s partly because I spent three years in full-time research / I was in another career / my home school had limited rotations during COVID. To compensate, I’ve intentionally done X, Y, and Z.”

Fill in X, Y, Z with specifics:

- Shadowing attending in your chosen specialty

- Longitudinal clinic 1 half-day/week

- Relevant online modules with cases (and what you learned)

- Simulation sessions, code blue training, OSCE work

- Extra call shifts you asked to join

Then pivot:

“What has been consistent in every setting is that I ask for feedback aggressively, I adapt fast, and I’m comfortable saying ‘I don’t know’ and then closing that gap quickly.”

This is what programs want from junior residents: not omniscience, but reliable, fast learners who are safe.

5.2 Show a Track Record of Steep Learning Curves

Residency is basically 3+ years of controlled drowning. People who learn fast and don’t crumble—gold.

So pick stories that highlight:

- Walking into a completely new environment

- Feeling behind

- Building a concrete plan

- Checking progress with feedback

- Ending up competent (or at least clearly improved)

Example pivot:

“I came into my first research year knowing almost nothing about data analysis. My mentor was explicit that if I couldn’t handle my own data, I wouldn’t be first author. I spent the first month doing structured learning at night—online courses, code review with a postdoc, and intentionally taking the more complex datasets. I asked for weekly feedback. Within four months I was the person others came to with R questions. I expect a similar curve my intern year—steep at first, but I’ve done this kind of ramp-up before.”

Notice: nothing clinical in that story, but the pattern is exactly what residencies want.

6. Pre-Engineer Your Answers to the Top Behavioral Questions

You don’t need to guess what you’ll be asked. There are maybe 15 core behavioral buckets that keep recycling with different wording.

Here’s how to attack them with limited clinical exposure.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Teamwork | 90 |

| Conflict | 85 |

| Failure | 80 |

| Ethics | 75 |

| Adaptability | 88 |

| Leadership | 70 |

| Patient Care Specific | 40 |

That “Patient Care Specific” bar is the only one that requires clinical content. Everything else can come from your broader life.

Core prompts and how you can approach them:

“Tell me about a time you failed.”

- Use: exam, Step, grant rejection, botched project.

- Emphasize: ownership, feedback, changed behavior, measurable improvement.

“Tell me about a time you had a conflict with a colleague.”

- Use: lab, job, group project, leadership.

- Emphasize: you did not gossip, you addressed it directly but professionally, you protected the mission (patient care analogue).

“Describe a stressful situation and how you handled it.”

- Use: job with deadlines, caregiving, crisis hotline, intense rotation even if short.

- Emphasize: prioritization, communication, self-regulation.

“Tell me about a time you received critical feedback.”

- Use: harsh attending eval, mentor tearing up a draft, boss critique.

- Emphasize: you didn’t get defensive (or if you did, you noticed and corrected), you implemented specific changes.

“Tell me about a time you made someone feel heard.”

- Use: non-medical conflict resolution, teaching, support role.

- Emphasize: specific listening behaviors, reflecting back, outcome.

Do not scramble on the spot. Map your existing story bank to these buckets now. That way, in the interview, when you hear “conflict,” your brain immediately pulls the lab authorship story or the team leadership story you already refined.

7. Use Process Stories To Prove You Can Function on the Wards

You don’t have as many “war stories,” fine. Then lean on process stories: how you think, how you organize, how you prevent problems.

Programs love:

- How you pre-round / organize patient data

- How you manage tasks under time pressure

- How you avoid dropping balls

- How you learn new information quickly and sustainably

Even with minimal clinical rotations, you can talk process.

Example:

“On my internal medicine rotation, I realized quickly that my biggest risk as a student with less prior clinical exposure was missing details. I built a standardized template for pre-rounding that I used for every patient—overnight events, vitals trends, labs flagged by significance, active problems, and one question or learning point for each. Before rounds, I’d run my assessments by the senior resident in 2–3 minutes. That structure kept me safe, efficient, and able to scale when my census went from 3 patients to 8. I plan to keep refining and scaling that system as a resident.”

That answer tells them: this person won’t just show up and drown silently.

8. Body Language, Demeanor, and What Your Face Is Saying

I’ve watched plenty of interviews where the content of the answer wasn’t the problem—the applicant’s face was.

If you already feel insecure about your limited clinical exposure, you’ll unconsciously:

- Shrink your posture

- Over-apologize

- Ramble to “prove” you know more than you do

- Sound like you’re asking for permission to exist

You can’t afford that.

Concrete fixes:

- Sit like you’re at the table for a reason: straight back, shoulders relaxed, feet planted.

- When acknowledging gaps, keep your voice steady and matter-of-fact, not ashamed.

- End answers with confidence in your growth, not with “hopefully I’ll be ready.”

- Practice on video. Watch for apologetic smiles and cringing when you talk about weaknesses.

If your content says “I learn fast and adapt” but your non-verbal signals say “please don’t find out I’m a fraud,” the committee will believe your body, not your words.

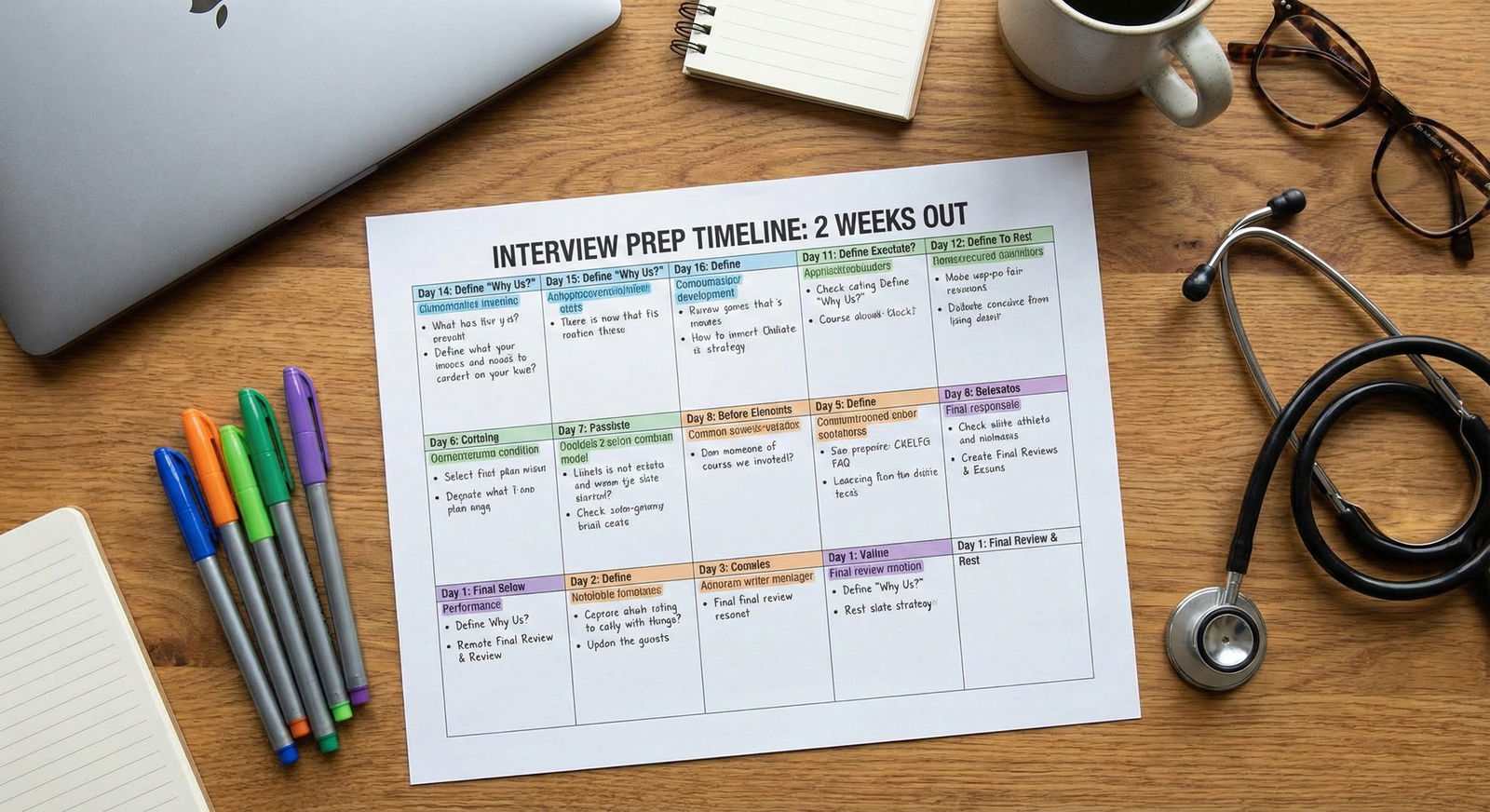

9. Rehearsal Plan for the Next 7–10 Days

You don’t need a 3-month course. You need a focused sprint.

Here’s a concrete, no-nonsense plan.

| Period | Event |

|---|---|

| Days 1-2 - Story Inventory | Build and categorize stories |

| Days 3-5 - Rewrite & Translate | Add STAR+Reflection, residency links |

| Days 6-7 - Mock Questions | Record practice sessions |

| Days 8-9 - Feedback Loop | Peer/mentor review, refine weak answers |

| Day 10 - Final Polish | Rapid-fire drills, confidence check |

Day 1–2:

- Build your 12–15 story inventory.

- Tag each: conflict, failure, leadership, teamwork, ethics, patient care, feedback, stress.

Day 3–5:

- For each story, write a rough STAR+Reflection outline.

- Note out loud the sentence that ties it back to residency.

Day 6–7:

- Generate a list of 25 common behavioral questions (google + this article’s list).

- Record yourself answering 10 per day. Two minutes max per answer.

Day 8–9:

- Send 3–5 recordings to someone who’ll be honest: mentor, chief resident, friend who interviews people in another field.

- Ask only three questions:

- Where did I sound weak or unsure?

- Where did I ramble?

- Which answer made you actually believe I’d be good on the wards?

Day 10:

- Do one full mock interview (behavioral-heavy) with a live person.

- After: immediately jot down which questions rattled you and refine those stories.

You can do all of this while still on rotations or working. It’s about focus, not volume.

10. One Hard Truth You Need To Hear

If your clinical exposure is limited because you chose research, or worked another job to support a family, or you’re an IMG with structural barriers—fine. Explain it clearly and show how it made you better.

If it’s limited because you coasted and avoided patient-facing work whenever possible—that will leak through in the interview. Your stories will feel like someone else’s life. Your answers about “why this specialty” will be thin. Your enthusiasm will sound rehearsed.

If that’s you, you’re not doomed. But you need to start fixing it now—not with more interview tricks, but with real, hands-on experiences: volunteer shifts, shadowing, extra clinic time, sim labs, anything that lets you interact with actual humans in distress.

Interview tactics can only amplify what’s already there. They can’t fabricate a real work ethic or actual interest in patient care.

FAQ (Exactly 3 Questions)

1. Is it okay to use non-medical examples for most of my behavioral answers?

Yes. Completely fine, as long as you do two things: pick serious, high-responsibility situations (not trivial roommate drama) and explicitly connect each story back to how it prepares you for residency. You’re being evaluated on your behavior patterns—accountability, communication, resilience, teamwork—not on whether every story occurred inside a hospital.

2. How do I answer if they directly ask about a “clinical mistake” and I truly have very little clinical exposure?

First, scan your rotations hard—often you’re underestimating smaller errors (missing a lab abnormality, communication failures, poorly organized presentations) that still count. If you genuinely can’t find a clear clinical mistake, be honest and pivot: acknowledge your limited exposure, then use a non-clinical but serious error (research data mishandling, work mistake, leadership error) and walk through how you recognized it, owned it, fixed it, and changed your process. End by stating how you plan to apply that same vigilance and humility to patient care as you gain more responsibility.

3. How do I stop sounding defensive when explaining my limited clinical experience?

Drop the over-justification. One clean sentence of context is enough (“My school had limited in-person rotations during COVID, so I pursued X and Y to compensate.”). Then spend 80–90% of your answer on what you did about it—extra efforts you made, feedback you sought, how quickly you’ve learned in new settings. Practice your tone: calm, factual, forward-looking. If you catch yourself repeating apologies or blaming others, rewrite that answer. You’re not begging for forgiveness; you’re presenting evidence that you understand the gap and have the habits to close it fast.

Open a blank document or notebook right now and list three real situations where you were under pressure and had to act—clinical or not. Label each one with “conflict,” “failure,” or “teamwork.” That’s the seed of your behavioral playbook. Build it before you’re sitting in front of a program director wishing you had.