The worst thing you can do with an ethics-based behavioral question is panic and say, “I have not really seen that before.”

You are going into residency. You will be expected to handle ethical problems on day one. So you must sound like someone who has thought about them, even if you have not personally lived every scenario.

You can absolutely answer ethics-based behavioral questions without direct experience. You just need a specific framework, a way to borrow from related experiences, and a clean structure that makes you sound thoughtful instead of inexperienced.

Here is how you fix this.

Step 1: Stop Thinking “Experience-Or-Else”

Most applicants get this wrong from the start. They treat behavioral ethics questions as:

“Tell me about the time you personally handled this exact ethical disaster.”

That is not what programs are testing. They want to know:

- How you think when there is no obvious right answer

- Whether you recognize stakeholders and consequences

- Whether you understand basic ethical principles in medicine

- Whether you will ask for help before doing something dangerous or unethical

They know many M4s have not dealt with whistleblowing, major medical errors, or a family demanding non-disclosure in a dramatic way. What they are really screening out is:

- People who are rigid and judgmental

- People who are reckless and “go rogue”

- People who cannot explain their reasoning

- People who throw others under the bus

So your job is not to manufacture a perfect dramatic case. Your job is to show:

“Even if I have not lived this exact scenario, here is how I would think through it systematically, grounded in my actual clinical and life experience.”

That is enough—if you present it correctly.

Step 2: Use This Simple Ethics Answer Framework (R-S-A-R)

You need a structure that works whether you have a perfect example or no direct experience at all.

Use R-S-A-R:

- R – Reframe the question

- S – Stakeholders and principles

- A – Action or approach

- R – Reflection / safeguard

This keeps you from rambling, moralizing, or saying “I am not sure what I would do” and dying on the spot.

1. Reframe the Question (1 sentence)

You buy yourself time and show you heard the problem clearly.

- “So if I understand, we have a conflict between the patient’s autonomy and the family’s wishes regarding disclosure.”

- “You are asking about a situation where a supervisor is behaving unprofessionally and I need to decide whether and how to escalate.”

Short. Clear. No fluff.

2. Stakeholders and Principles (1–3 sentences)

You do not need to recite Beauchamp and Childress, but you do need to show that your head is in the right ethical space.

Name:

- The main stakeholders (patient, team, institution, family, trainee)

- The main ethical principles in conflict (autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, justice, professionalism, honesty)

Examples:

- “I would first think about who is affected: the patient, their family, the team caring for them, and the institution’s standards.”

- “The main tension here is between honesty/transparency and the risk of causing harm or losing trust.”

3. Action or Approach (this is the core)

Answer in terms of:

- What you would do if you have no direct story

- What you did do if you have any related story at all

Use a process:

- Gather information and context

- Clarify patient preferences / safety

- Seek guidance appropriately (senior, ethics, policies)

- Communicate clearly and respectfully

- Document and follow institutional policies

For example:

- “My first step would be to clarify what the patient actually wants, privately if necessary, and confirm their decision-making capacity.”

- “I would then seek guidance from my senior resident or attending and, if needed, involve risk management or ethics, because these cases usually have hospital policies.”

You are showing: I do not wing it. I have a sequence.

4. Reflection / Safeguard (1–2 sentences)

Wrap with humility and safety.

- “I recognize as a resident I may not have the full picture, so I would be careful to involve my attending early while still advocating for the patient’s rights.”

- “I would reflect afterward on how I handled it and, if possible, debrief with a mentor so I can improve for the next time.”

This final piece makes you sound mature instead of rehearsed.

Step 3: How To Answer When You Truly Lack Direct Experience

Let me be blunt: saying “I have not encountered that” and stopping there is a bad answer.

You fix it with a three-part pivot:

- Acknowledge the lack of direct experience

- Borrow a related example (clinical or non-clinical)

- Then apply the hypothetical framework

1. Acknowledge Briefly (Do Not Apologize)

One sentence. Then move on.

- “I have not seen that exact situation clinically.”

- “I have not personally had to report a major safety incident like a retained foreign object.”

Do NOT:

- Over-explain why you have not seen it

- Blame your school, rotations, or attending

You are not on trial.

2. Borrow a Related Example

You probably have something:

- A minor professionalism issue on a team

- A confidentiality concern (friends/family asking for info)

- A small med error or near-miss

- A conflict between patient wishes and family expectations

- A group project where someone was cutting corners

You are allowed to say:

- “While I have not seen that exact scenario, I have faced a similar ethical tension when…”

Then briefly summarize:

- Setting (rotation / context)

- Ethical tension

- Your role

- What you did, in 2–3 sentences using R-S-A-R

3. Then Add the Hypothetical “If This Exact Case Happened…”

After your related example:

- “If I encountered the specific situation you described, I would approach it in a similar structured way…”

Then run your R-S-A-R on the hypothetical.

This does three things:

- Shows you actually have some lived basis for your thinking

- Proves you can transfer skills across situations

- Avoids the awkward “I have literally nothing to say here” dead space

Step 4: Common Ethics Question Types and Ready-Made Structures

Let us get concrete. These are the classics you will see in residency interviews.

I will give you:

- What they are really testing

- A clean way to structure your answer

- Example language you can adapt

Scenario 1: “You Witness an Attending Behaving Unprofessionally”

Example prompts:

- “Tell me about a time you saw someone in a position of authority behaving unprofessionally. What did you do?”

- “What would you do if your attending made an inappropriate comment about a patient?”

They are testing:

Judgment, respect for hierarchy without blind obedience, how you handle power dynamics, whether you protect patients and colleagues.

If you have an example (even a mild one):

Use:

- Brief context

- What concerned you ethically (respect, safety, professionalism)

- What you did (clarify, address directly if safe, escalate if needed)

- Outcome and what you learned

Sample structure:

- “On my [rotation], an attending made a sarcastic remark about a patient’s weight during rounds, in front of the team. It was not directly harmful to the patient, but it set a tone I was uncomfortable with.”

- “Ethically, this raised concerns about respect and professionalism. As a student, I wanted to balance respect for hierarchy with maintaining a safe environment.”

- “I did not challenge them in front of everyone, but later that day I approached my senior and asked for advice on how to handle it. Together we agreed that the best step was for the senior to bring it up privately with the attending, framing it around team culture and patient respect.”

- “After that, I saw a noticeable shift in how that attending spoke during rounds. It taught me that even as a learner, I can contribute by raising concerns to someone in a position to act.”

If you do NOT have an example:

- “I have not personally seen a blatant case of egregious unprofessional behavior from an attending. The closest example was…” [share a mild situation].

- Then: “If I did see clearly inappropriate behavior that affected patient safety or team culture, I would first make sure the patient was safe, then seek guidance from a trusted senior resident or another attending to discuss how to escalate appropriately, following institutional policies.”

Scenario 2: “Patient Autonomy vs Family Wishes”

Example prompts:

- “What would you do if a competent patient did not want their diagnosis disclosed to family, but the family is demanding the information?”

- “Tell me about a time when you had to balance family wishes with what the patient wanted.”

They are testing:

Do you understand autonomy, confidentiality, capacity, and how to manage family dynamics without being a pushover.

Structure:

- Reframe: autonomy vs family preference

- Confirm capacity and patient’s clear wishes

- Protect confidentiality, involve senior

- Communicate with family without breaching PHI

- Reflection

Example answer skeleton:

- “That scenario is a classic tension between patient autonomy/confidentiality and family expectations.”

- “My first step would be to confirm that the patient has decision-making capacity and understands the implications of withholding information from their family.”

- “If the patient is capacitated and clear that they do not want information shared, I would respect that, while explaining to the family in general terms that I must follow the patient’s wishes and privacy laws.”

- “I would definitely involve my senior resident or attending early, and, if available, social work or ethics, because these situations can quickly become emotionally charged.”

- “As a trainee, I would also reflect afterward on how I handled those conversations and seek feedback from the attending on my communication.”

If you have seen any version of this (even a patient refusing visitors, or not wanting parents informed in adolescent medicine), plug it in as your “related example” first.

Scenario 3: “You Notice a Potential Medical Error”

Example prompts:

- “Tell me about a time you caught a mistake.”

- “What would you do if you realized your team had ordered the wrong medication for a patient?”

They are testing:

Patient safety culture, willingness to speak up, humility, and ability to handle mistakes without getting defensive.

Structure:

- Brief background

- What triggered your concern (specific detail)

- How you verified before acting

- How you raised it (tone, respect, clarity)

- Outcome and learning

Example (with experience):

- “On my medicine rotation, I noticed a heparin drip order that used the wrong weight. The dose seemed unusually high for the patient.”

- “This raised concerns about patient safety and nonmaleficence, so I double-checked the chart and previous notes to confirm there was no intentional reason for the deviation.”

- “Once I confirmed it looked like an error, I immediately brought it to the attention of the intern, framing it as a question: ‘I may be missing something, but I noticed…’ We rechecked together, updated the order, and informed the attending.”

- “The patient did not experience harm, and it reinforced for me that speaking up, even as a student, is essential to a culture of safety.”

If you have never caught an error, use something small: mislabelled lab, incorrect patient room, or even a near-miss on the wrong patient chart, then broaden with:

- “If I realized I had personally made a serious error, I would prioritize patient safety, immediately inform my team, and participate in transparent disclosure and reporting per hospital policy, rather than trying to minimize or hide it.”

Scenario 4: “You Disagree With Your Team”

Example prompts:

- “Tell me about a time you disagreed with a plan of care.”

- “How would you handle an ethical disagreement with your attending?”

They are testing:

Whether you can disagree respectfully and whether you understand your role in hierarchy.

Structure:

- Set up the disagreement (no dramatics, no character assassination)

- Show you sought to understand first

- Explain how you voiced concern

- Describe outcome and what you took from it

Example:

- “On my surgery rotation, I was concerned about discharging a patient who still seemed unstable from a nursing perspective, even though the medical criteria were technically met.”

- “I asked the resident if we could review the case again, framing it around my specific concerns: vital sign trends and the nursing report.”

- “We discussed it together and the resident ultimately agreed to keep the patient another night. It reinforced for me that raising concerns respectfully, with concrete data, is usually welcomed rather than seen as insubordinate.”

- “If I were to disagree with an attending on an ethical issue as a resident, I would still start privately and respectfully, bringing specific data and patient-centered reasoning, and involve another senior or ethics if there was a serious unresolved safety concern.”

Step 5: Practice Converting Weak Experience Into Strong Ethical Answers

Your problem is not lack of experience. Your problem is that you are not mining what you already have.

Grab a sheet. Make three columns:

- Actual event (even small)

- Ethical tension

- Principles and stakeholders

Then work each into R-S-A-R.

You can turn “my classmate cheated on an online quiz,” or “I had a conflict with a co-volunteer,” into an ethics answer if you:

- Are explicit about the ethical issue (honesty, fairness, professionalism)

- Make your role clear (what you did and why)

- Avoid trashing other people

| Event Type | Ethical Theme | Usable For Questions About |

|---|---|---|

| Minor med error caught | Safety, honesty | Errors, reporting, teamwork |

| Team conflict | Respect, justice | Disagreements, leadership |

| Cheating observed | Integrity, duty | Professionalism, honesty |

| Confidential info asked | Privacy, autonomy | HIPAA, boundaries |

| Unequal workload | Fairness, respect | Teamwork, advocacy |

You should aim to have at least:

- 2 examples about safety and errors

- 2 about professionalism / behavior

- 1 about confidentiality / boundaries

- 1 about conflict / disagreement

Those six can be adapted to answer 80% of ethics-based behavioral questions.

Step 6: Avoid These Common Mistakes That Kill Your Credibility

A few things will instantly flag you as risky:

- Hero narratives – You single-handedly fixed a huge institutional problem as an M3. No one believes it.

- Blame and gossip – You spend more time talking about how bad the other person was than your own reasoning.

- Vague “I’d just talk to them” answers – No sequence, no specifics, just “communicate better.” Useless.

- Ignoring your role limits – Saying you’d override an attending’s orders as an MS4. That is fantasy.

- Absolute moralizing – “I would always…” or “That is completely unacceptable in every case.” Life is messier than that.

Instead, aim for:

- Concrete actions

- Respectful escalation

- Clear understanding of your level of authority

- Willingness to ask for help

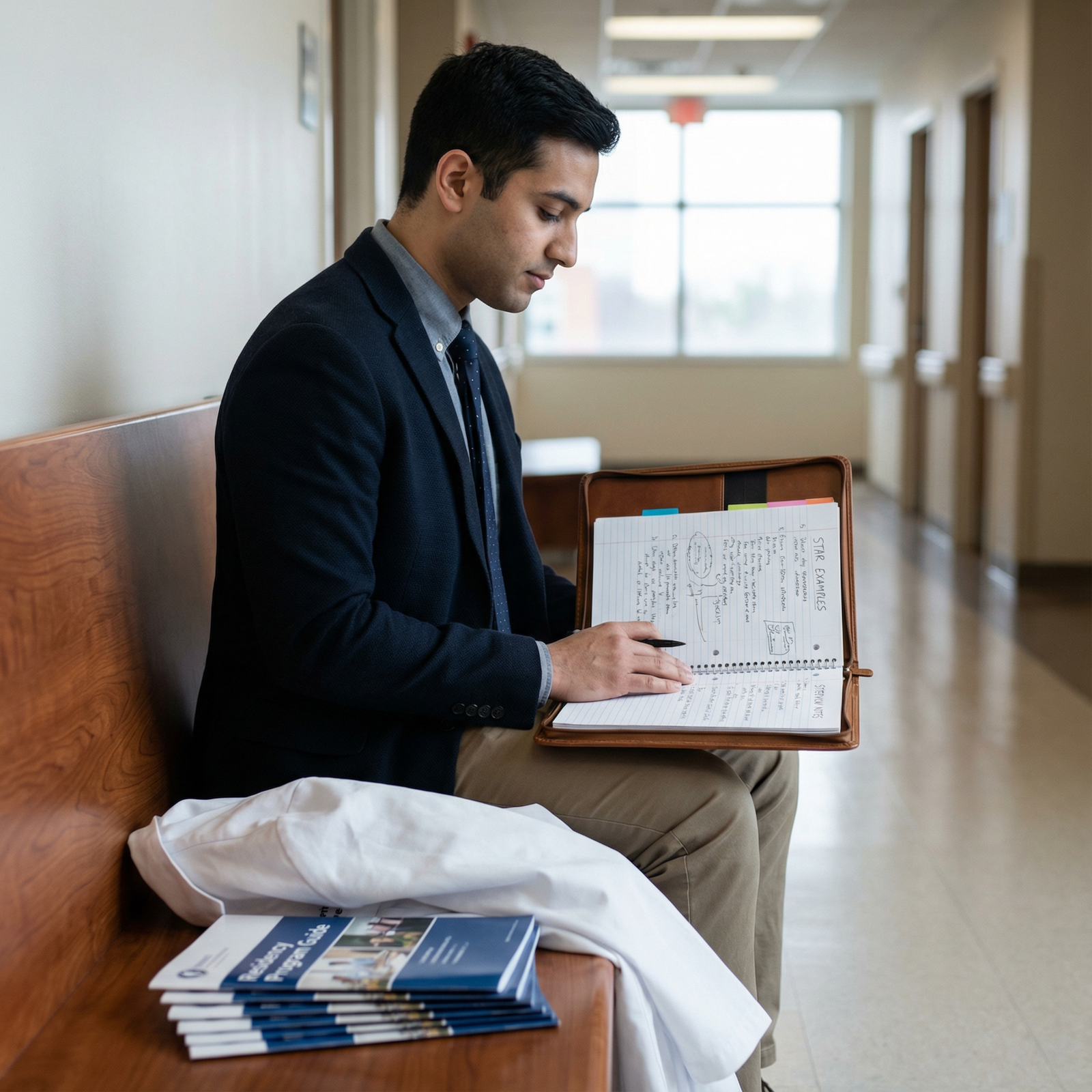

Step 7: Build a One-Page Ethics “Cheat Sheet” Before Interviews

If you walk into interviews with everything only in your head, you will default to rambling.

Create a one-page document (yes, literally):

Section 1: My Core Principles (3–4 bullets)

- “Protect patient safety and autonomy.”

- “Be honest and transparent, within my role and policies.”

- “Seek help early when stakes are high.”

- “Treat colleagues and staff with respect, even when correcting problems.”

This gives you consistent language.

Section 2: My 6 Anchor Stories

List:

- Situation title

- Ethical theme

- 1–2 keywords per step (R-S-A-R)

Example:

- “Heparin dose concern – Safety / Nonmaleficence – noticed odd dose / asked intern / corrected / learned value of speaking up”

You are not reading this in interviews, obviously. But having built it makes your responses sharper.

Section 3: Generic “If I Have Not Seen It” Phrase Bank

Pre-write 3–4 sentences you can reuse:

- “I have not seen that exact scenario, but a related experience was…”

- “If I faced that situation as a resident, my approach would be to first ensure patient safety, then involve my senior and follow institutional policies while advocating for the patient.”

- “Given my role as a trainee, I would be careful not to act independently beyond my scope, but I would also not ignore a serious ethical concern.”

That alone will prevent the awkward silence many applicants fall into.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Get Question |

| Step 2 | Pick Related Story |

| Step 3 | Pick Closest Analog |

| Step 4 | Apply R-S-A-R to Real Event |

| Step 5 | Acknowledge Lack & Share Analog |

| Step 6 | Apply R-S-A-R to Hypothetical |

| Step 7 | End With Reflection |

| Step 8 | Direct Experience? |

Step 8: Rehearse Out Loud Like You Mean It

Ethics answers fall apart when they sound memorized or overly academic.

You need to practice:

- Out loud

- With a timer (60–90 seconds per answer)

- With a real person or a recorder

Pick 5 common prompts:

- “Tell me about an ethical dilemma you faced.”

- “Tell me about a time you made a mistake.”

- “What would you do if you saw a colleague cutting corners?”

- “How would you handle a family asking you to lie to a patient?”

- “Describe a time you advocated for a patient.”

For each:

- Jot down R-S-A-R bullets

- Answer out loud

- Listen back and cut fluff

You want to sound like:

- You think systematically

- You care about patients and colleagues

- You know your level and ask for help early

Not like:

- You memorized an ethics textbook

- You are trying to show off vocabulary

- You are desperately stretching a weak story

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Too Short | 30 |

| Ideal | 75 |

| Too Long | 180 |

Step 9: Calibrate For Different Specialties

Ethical expectations are the same across medicine, but emphasis changes slightly by specialty.

For psychiatry / family med / peds:

- Lean harder on autonomy, confidentiality, longitudinal trust, and family dynamics.

- Include examples with sensitive topics: mental health, adolescent confidentiality, social determinants.

For surgery / EM / ICU:

- Emphasize patient safety, decisiveness, chain of command, and dealing with high-stakes errors or near-misses.

- Show you can act quickly while still respecting hierarchy.

For OB/GYN / IM subspecialties:

- Focus on consent, reproductive ethics, resource allocation, and complex risk–benefit discussions.

You do not need different stories for each specialty. You just highlight different aspects of the same core examples.

Step 10: Quick Repair Kit For When Your Answer Goes Sideways

Sometimes you will start answering and realize halfway through: this is going nowhere.

Here is how you salvage it:

Pause and re-anchor

- “To summarize the key point…”

- “Stepping back, the main issue for me in that situation was…”

Name the principles

- “This really came down to balancing honesty and patient safety.”

State 1–2 concrete actions you took or would take

- “That is why I involved my senior immediately and made sure the patient’s immediate safety needs were addressed.”

End with reflection

- “Looking back, I would still prioritize speaking up early, even if I might phrase things more clearly next time.”

Interviewers are not looking for perfection. They are looking for whether you can recover, think clearly, and keep patients safe.

Key Takeaways

- You do not need dramatic ethical war stories. You need a clear, repeatable framework (R-S-A-R) and a few modest but real examples.

- When you lack direct experience, explicitly pivot: admit it briefly, use the closest related story, then walk through how you would handle the specific hypothetical.

- Programs care far more about your reasoning, humility, and safety mindset than about whether you have lived every scenario. Show them you think like a resident, not a bystander.