It is January 10th. You survived interview season. Your calendar is finally quiet. But your brain is not.

A few programs on your list felt… off. A vague comment about “recent changes in leadership.” Residents who dodged your question about workloads. A Step score “preference” that sounded suspiciously like a hard cutoff. You smiled during the Zoom, said thank you, logged off, and told yourself you would “look into it later.”

It is now later.

This is the window—January and February—when you systematically re-check data on potentially risky programs before you lock in your rank list. At this point, you are not gathering everything on everyone. You are triaging: confirming which programs are safe enough to rank confidently, which are “only if I have to,” and which are so problematic they should drop to the bottom or off the list entirely.

Below is a structured, time-based plan for how to do that without losing a week to Reddit doomscrolling.

Week 1 of January: Build Your “Risk List” and Framework

At this point you should not be randomly Googling programs. You should be deciding where to focus.

Step 1: Create your “Risky Programs” list (1–2 days)

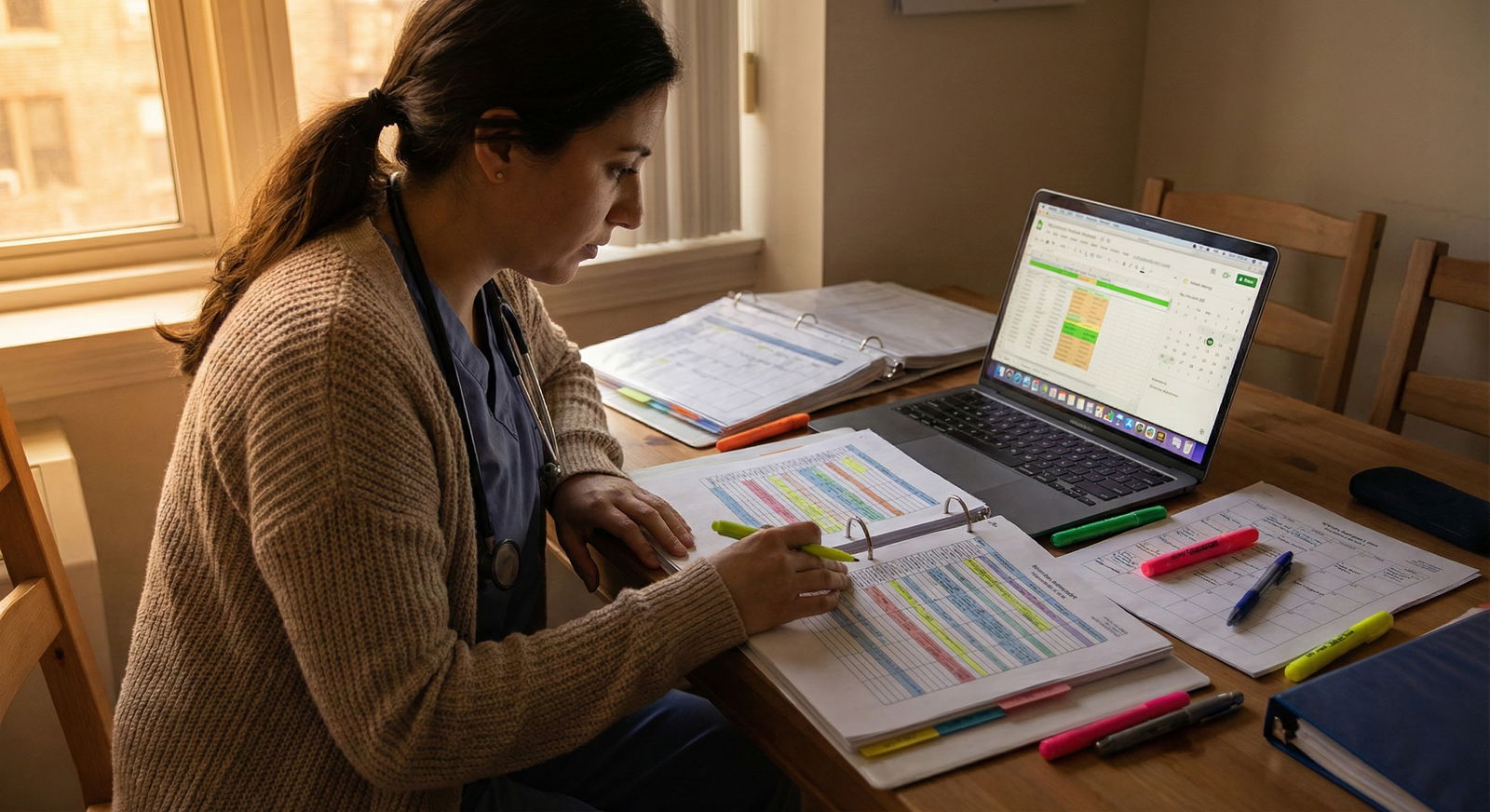

Open a spreadsheet. One tab only. Keep it simple.

Columns I recommend:

- Program name

- Specialty

- City / state

- Interview date

- Initial gut impression (1–5)

- Specific concern(s)

- Flags found (checklist)

- Overall risk category (Low / Medium / High)

- Final rank tier (Top / Middle / Bottom / Do not rank)

Now, from memory, list:

- Programs where residents seemed unhappy or guarded.

- Programs with vague answers about:

- Case volume

- Fellowship match

- Didactics

- Schedule changes

- Programs with:

- New PD or chair in last 2–3 years

- Recent hospital merger or acquisition

- Oddly high number of unfilled spots last year

- Programs in cities you would only tolerate if the training were phenomenal.

You will probably end up with 5–20 programs. That is your risk list. Everyone else you leave alone except for minor spot-checks.

Step 2: Decide what “risky” means to you (half a day)

You need criteria or you will drown in details.

Here is the structure I push applicants to use:

| Category | Low Risk Example | High Risk Example |

|---|---|---|

| ACGME Status | Full accreditation, stable | Warning, probation, new program |

| Resident Culture | Candid, neutral to positive | Fearful, evasive, openly negative |

| Workload / Coverage | Busy but supported | Chronic call coverage gaps |

| Leadership Stability | PD >3 years, consistent messaging | Recent PD turnover, conflicting messages |

| Outcomes | Predictable boards & fellowship | Poor boards, unclear fellowship placement |

Define your personal thresholds. For example:

- Any program with ACGME warning = automatically bottom tier or “do not rank.”

- Any program where more than one resident hinted at “toxic leadership” = at least Medium risk.

- Any program that cannot show a basic case log pattern or clear board pass support = Medium to High risk.

Write those rules at the top of your spreadsheet. You will forget them later if you do not.

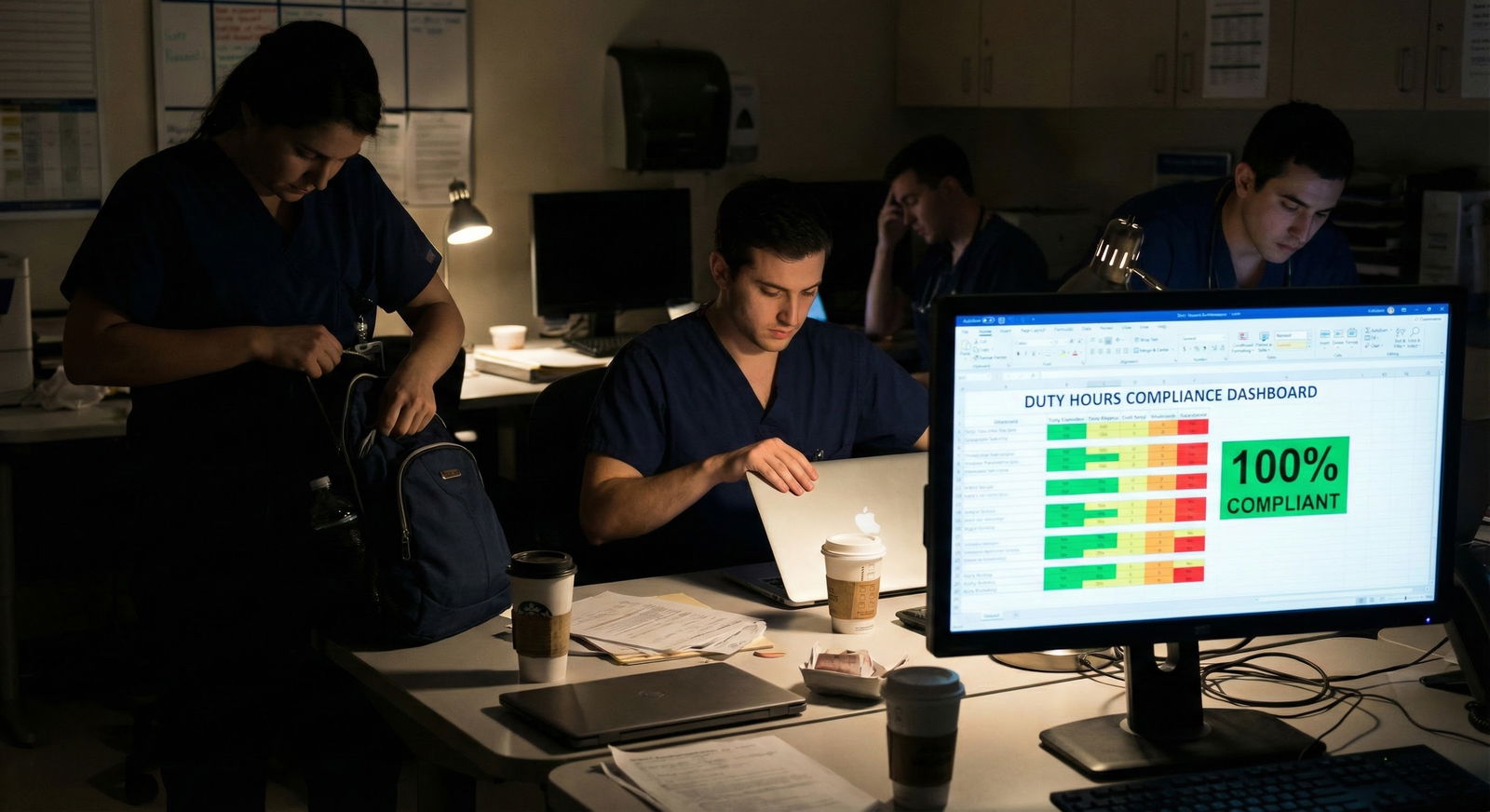

Week 2 of January: Hard Data Check – Accreditation, Fill History, Objective Outcomes

At this point you should verify that the floor is not falling out from under any program. Objective, external data first. Stories and vibes second.

Day 1–2: Accreditation and official status

You start with ACGME and official sources. Not Reddit. Not SDN.

- Go to ACGME’s public program search.

- For every program on your risk list, check:

- Accreditation status (Full, Initial, Continued, Warning, Probation)

- Length of accreditation cycle

- Recent name or sponsorship changes

Here is how you interpret what you see:

- Full accreditation, regular cycle: Good. Not a green light for everything, but you are not on a sinking ship.

- Initial accreditation: New or recently restructured program. Neutral to risky depending on leadership and hospital stability.

- Warning / Probation: Serious. Occasionally fixable, but you should assume smoke = fire until you find compelling contrary evidence.

If you see Warning or Probation and they never mentioned it on interview day, that is a character issue from leadership. I have seen that alone justify dropping a program down a tier.

Day 3: NRMP fill data and match performance

Next you check how the program has done in the Match over several years.

Use:

- NRMP “Results and Data” PDFs

- Specialty-specific match reports

- Sometimes state / regional GME consortia reports

You are looking for patterns, not one-off blips.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| 2019 | 100 |

| 2020 | 100 |

| 2021 | 75 |

| 2022 | 80 |

| 2023 | 85 |

If your target program is one of the ones repeatedly:

- Not filling

- Relying heavily on SOAP

- Or dropping in size

That is a red flag. Not because “unpopular = bad,” but because it often tracks with:

- Poor reputation among current residents and applicants

- Leadership chaos

- Overwork without education

Note: One weird year in 2020–2021 is less meaningful. A three-year decline is not an accident.

Day 4–5: Objective outcomes – boards and fellowships

Now you move to outcomes. You will not get perfect data. You just need “reasonable and consistent.”

Look for:

- Board pass rate (3–5 year rolling if they provide it)

- Recent fellowship matches (if relevant to your specialty)

- Where graduates work (hospital websites, alumni pages, LinkedIn if you must)

You want to see:

- Clear pattern of board support and passing

- Graduates landing in jobs or fellowships that you would be content with

What you do NOT want:

- Hand-wavy “we support our residents to succeed” but no numbers

- One superstar fellow match used as marketing, but silence on the rest

- Obvious mismatches between what PD said and what the data show

Aim to classify each program on your list:

- Outcomes solid and consistent → Low risk on this dimension

- Mixed / unclear → Medium risk, needs context from residents

- Poor or hidden → High risk unless contradicted by very strong first-hand reports

Update the “Flags found” and “Risk category” columns accordingly.

Week 3 of January: Soft Data – Resident Experience, Culture, Workload

At this point, you have done the cold external review. Now you go inside the building.

Day 1–2: Re-analyze your interview notes

Do not trust memory alone. It is biased.

Pull up:

- Your written notes from interview day

- Any unofficial impressions you jotted down that night (including “this place felt off”)

Systematically review your notes for each risky program:

Did multiple residents:

- Laugh awkwardly when asked about hours?

- Say “we are working on that” about something critical like education or staffing?

- Go quiet or change subject when leadership was mentioned?

-

- Dodge questions about resident feedback mechanisms?

- Emphasize service volume but almost never say the word “teaching”?

- Over-sell “we are like a family” without concrete support structures?

You are looking for patterns across different people in the same program. One weird PGY-1 is noise. Three residents and a PD all avoiding the same topic is signal.

Day 3–4: Controlled online reconnaissance

Now, carefully, you look online. The key word is controlled. Set a time limit per program or you will lose days.

Sources:

- Reddit / r/Residency / specialty subs

- SDN specialty threads

- Specialty-specific Discords or Slack groups (if you are already in them)

- Program reviews on third-party sites (weak but sometimes interesting)

You are not looking for “one bad story.” That is anecdote. You are looking for:

Repeated, consistent complaints about:

- Program director being punitive or retaliatory

- Unsafe patient loads

- Bait-and-switch on schedule or night float

- Bullying or discrimination brushed aside

Recurring phrases like:

- “Run, do not walk”

- “Used to be good, went downhill after new leadership”

- “Everyone is trying to leave”

That is usually not noise.

Limit this to:

- 20–30 minutes per high-risk program

- 10–15 minutes for medium risk

- 0 minutes for low risk unless you are truly undecided

Log what you see in plain language in your sheet. Example: “Reddit 2023–24: 5+ posts about malignant culture, 2 about gaslighting from PD, no positive counterpoint.”

Day 5–6: Direct back-channeling (optional but powerful)

At this point, the most valuable data often comes from discrete, person-to-person channels.

Reasonable back-channels:

- Upper-levels from your home program who rotated there

- Recent grads who matched there

- Fellows or attendings who trained there or work with their graduates

Send concise, focused messages. For example:

“I am ranking X program and had some concerns about leadership support and workload. Would you feel comfortable sharing whether residents generally feel supported, and if there are any big issues you would want your own trainee to know about?”

Key rule: You are asking for broad themes, not gossip on specific people.

If multiple independent people say the same thing (“brutal call, no teaching, lots of people trying to leave”), treat that as hard data.

Week 4 of January: Synthesize and Re-Tier Your List

Now you stop collecting. You start deciding.

Day 1: Categorize risk for each program

Using all the data, assign each program:

- Risk: Low / Medium / High

- Reason: 1–2 sentence justification, not a novel

Example entries:

- “Medium – New PD + initial accreditation. Residents seemed cautious but not miserable. Good case volume, outcomes unclear.”

- “High – ACGME warning status, repeated online comments about toxic PD, recent wave of residents transferring out.”

Day 2–3: Create rank “tiers” before exact order

At this point, exact numerical order is premature. Build tiers instead.

I like:

- Tier 1: Would be happy to match here

- Tier 2: Acceptable, but not ideal

- Tier 3: Only if I must match somewhere

- Tier 4: Do not rank

Then, combine your gut preference with the risk category:

- High preference + Low risk → Tier 1

- High preference + Medium risk → Tier 1 or 2, depending on your risk tolerance

- Low preference + Medium/High risk → Tier 3 or 4

You can live with some risk at programs you genuinely like. But matching at a place you already dislike that is also high risk? That is how burnout starts on day one.

Early February: Re-Check After “New Info” and Emotional Drift

By early February, rumors start flying. “I heard X is putting residents on a new float system.” Or “Apparently the PD at Y is stepping down.” This is where people panic and re-arrange their rank list based on half-truths.

At this point, you should do a constrained re-check, not a full rebuild.

Step 1: One more accreditation and website sweep (1–2 days)

Revisit:

- ACGME program pages

- Program websites

- GME office announcements

You are looking for:

- Sudden leadership changes

- Major restructuring of the program

- Hospital financial crises, closures, or mergers

If a PD changed between your interview and February and no one told you, that is not inherently bad, but it is unstable. You downgrade slightly unless you have strong, trusted reassurance about the new leadership.

Step 2: Clarify only the most serious new concerns

If you hear a serious negative rumor (e.g., “half the PGY-2 class is leaving”), you do not:

- Spend 10 hours on internet sleuthing

- Rewrite your whole list at 2 a.m.

Instead, you:

- Identify 1–2 credible sources (alumni, trusted faculty).

- Ask a very targeted question:

- “I have heard there have been recent resident departures from X program. Is that accurate, and if so, does it reflect long-term issues?”

- Give yourself a deadline:

- If you do not get clear confirmation within a week, you proceed with the best data you have, weighting the uncertainty but not letting it dominate.

Mid to Late February: Final Rank List Decisions With Risk in Mind

This is the last pass. You are not hunting new data anymore. You are deciding how much risk you can live with.

At this point, you should have:

- A spreadsheet with:

- Every program you interviewed at

- Risk category

- Tier assignment

- Brief rationale

Now you structure your final rank list.

Step 1: Lock your “do not rank” group

Anything that hits one or more of these:

- ACGME probation or major warning, with no clear recovery

- Multiple consistent, credible reports of malignant culture

- You would be actively miserable living there even if training were good

Move them to “Do not rank” and stop thinking about them. Leaving them on your list “just in case” is how people end up trapped in programs they knew they should have avoided.

Step 2: Order within tiers using risk as a tiebreaker

For pairs of programs you like equally:

- Prefer stable leadership to leadership chaos

- Prefer transparent, average outcomes to opaque “we are excellent”

- Prefer clear resident advocacy structures (GME committee, grievance procedures used and respected) over vague “open door policy”

If Program A and Program B feel similar, but A has:

- Full accreditation

- Consistent fill

- Honest residents

And B has:

- Recent PD turnover

- Uneasy resident comments

- Mixed online chatter

Rank A higher. This is not complicated.

Step 3: Accept rational risk where growth is high

Risk is not automatically bad. Some “edgier” programs with new leadership are on their way up. Sometimes you bet on the right PD and get outstanding training.

Reasonable calculated risk:

- New PD with a strong reputation from a stellar institution

- Initial accreditation program in a strong hospital system with visible support

- Very busy safety-net program that is intense, but with clearly supportive leadership and honest residents

If training and growth are high, and red flags are about “hard work” rather than “abuse” or “dishonesty,” placing those programs higher is rational.

Quick Visual: What You Should Be Doing Each Week

| Period | Event |

|---|---|

| January - Week 1 | Build risk list and criteria |

| January - Week 2 | Check accreditation and match data |

| January - Week 3 | Review culture, online data, back-channels |

| January - Week 4 | Synthesize and tier programs |

| February - Early Feb | Re-check for major changes |

| February - Mid Feb | Finalize rank tiers with risk |

| February - Late Feb | Submit final rank list |

What Red Flags Actually Matter Most?

A lot of applicants obsess over the wrong things. “Do they have free food?” Not important. “Do interns have single rooms on night float?” Nice, not decisive.

The red flags that actually predict misery:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Toxic leadership | 95 |

| Unsafe workload | 90 |

| Accreditation issues | 80 |

| Poor board support | 75 |

| Minor perks (parking, food) | 20 |

High-impact red flags:

- Toxic, retaliatory, or dishonest leadership

- Chronic unsafe workloads without meaningful attempts to fix them

- Ongoing accreditation problems

- Culture where concerns are punished, not addressed

Medium impact:

- High service / low teaching, but honest about it

- Location strain (cost of living, commuting) that you can realistically manage

Low impact:

- Parking annoyances

- Cafeteria quality

- Slightly older facilities

During January and February, spend 90% of your energy on the first group, 10% on the second, and almost none on the third.

A Simple Comparison Snapshot

If you want a fast side-by-side for your top risky programs, build something like this:

| Factor | Program A | Program B | Program C |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACGME Status | Full | Warning | Initial |

| PD Tenure (years) | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| NRMP Fill (3 yrs) | 100% | 80% | 100% |

| Resident Culture | Neutral | Negative | Positive |

| Overall Risk | Low | High | Medium |

You will know very quickly which one should sit higher on your list.

Final Check: Keep Your Head, Not Just Your Heart

You are not trying to predict the future with perfect accuracy. You are trying to avoid obviously bad bets.

To close this out:

Three key points:

- January is for structured data gathering: accreditation, fill history, outcomes, and resident culture. No endless, directionless Googling.

- February is for small, targeted updates and final ranking decisions, not for blowing up your list because of one rumor.

- High-impact red flags—leadership toxicity, unsafe workload, accreditation problems—deserve real weight. Minor perks do not.

If you follow that timeline, you will go into rank list certification with something most applicants do not actually have: a clear, defensible reason for where every risky program sits.