The obsession with prestige is misplaced. The single most predictive red flag in residency is not the name, not the NIH funding, not the fellowship match list. It is the residency attrition rate.

If you want a crisp threshold: once a program’s true attrition rate pushes much above 5–7% per year, the data say you should be on high alert. Double‑digit attrition is not “bad luck.” It is a structural problem.

Let me walk through the numbers so you can see why.

1. What “attrition” actually means (and why programs play games with it)

First, vocabulary. When I say “attrition” here, I mean residents who leave a program before graduating for any reason:

- Dismissal or non‑renewal of contract

- “Voluntary” resignation or transfer

- Switching specialties

- Leaving medicine altogether

Programs try to slice this in softer ways: “voluntary vs involuntary,” “personal reasons,” “career change.” From an applicant’s risk perspective, that nuance matters less than you think.

From your vantage point, the key question is:

Out of 100 people who start here, how many actually finish here?

Not “how many find themselves,” not “how many decide to pursue another passion.” How many complete training in this program.

The problem: many programs under‑report. A PGY‑2 who is told “maybe this is not the right fit; we support your decision to leave” is often coded as a voluntary attrition. It looks softer on paper. The pain is the same for the resident.

So when we talk thresholds, I will assume that any reported attrition is a lower bound on the real number.

2. What the national data actually show

Let us anchor this in numbers, not folklore.

Across U.S. residency programs, multiple studies and ACGME reports converge on a few consistent patterns:

- Overall GME attrition is roughly 3–5% over the entire length of training for most core specialties.

- Certain specialties are higher, especially early years (e.g., general surgery, some surgical subspecialties, categorical psychiatry in some eras).

- Non‑categorical or prelim positions obviously have “attrition” by design, so focus on categorical tracks only when you evaluate risk.

A reasonable composite from published data (NRMP, ACGME, and specialty‑specific analyses) looks approximately like this for categorical programs:

| Specialty | Typical Total Attrition (All Years) |

|---|---|

| Internal Medicine | 2–4% |

| Family Medicine | 2–5% |

| Pediatrics | 2–4% |

| Psychiatry | 4–7% |

| General Surgery | 10–20% |

| OB/GYN | 6–10% |

These are aggregate, multi‑year, multi‑program numbers. The distribution is skewed: many programs have 0–2% attrition, and a minority have chronic double‑digit loss.

So if you see a program with 15% of residents gone across a recent 5‑year span, that is not “normal variance.” Statistically, that is a screaming outlier.

3. The math: how small annual losses become big lifetime risk

Applicants consistently underestimate compounding attrition.

You do not care only about the chance you leave in PGY‑1. You care about the chance you complete your entire training at that program. Different question.

Look at a simple model: assume an annual attrition rate that is constant across years. The probability of finishing a 3‑year residency at that program is:

Completion probability = (1 − annual attrition rate)³

For a 5‑year program, it is (1 − rate)⁵.

Here is what that looks like:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| 0% | 100 |

| 2% | 94 |

| 4% | 89 |

| 6% | 84 |

| 8% | 79 |

| 10% | 73 |

| 15% | 61 |

Interpretation:

- 2% annual loss → ~94% of residents finish.

- 6% annual loss → ~84% finish. That means 16 out of 100 residents will not complete at that program.

- 10% annual loss → ~73% finish. 27 out of 100 do not make it to graduation there.

For a 5‑year general surgery program, an annual 6% attrition becomes:

(1 − 0.06)⁵ ≈ 0.74 → 74% completion; 26% do not finish there.

These are not small differences. These are your odds of a multi‑year life upheaval.

So when you see an overall “20% attrition over 5 years,” that is mathematically equivalent to roughly 4–5% losses per year compounding. Which is already in the yellow zone.

4. Where the alarm bells should ring: practical thresholds

Let me give you concrete thresholds, not hand‑waving.

Green zone: ≤2% annual attrition (≈≤5% over all years)

Programs where almost everyone who starts, finishes. You see this a lot in:

- Strong, stable internal medicine programs

- Well‑run pediatrics and family medicine residencies

- Some high‑support psychiatry programs

If a categorical program has lost 0–1 resident in, say, 60–90 total resident‑years (for example, 20 residents per year × 3 years), that is a very safe signal.

Your interpretation: attrition here is likely driven by rare personal or catastrophic events, not systemic problems.

Yellow zone: 2–5% annual attrition (≈5–12% total)

At this level, you will see a few departures every cycle.

For a medium‑sized IM program with 60 residents:

- 2–5% annual attrition → about 1–3 residents gone per year.

Sometimes this is explainable: someone switched to radiology, someone had family issues and moved, one resident struggled academically. That is life.

But programs in this band deserve scrutiny, not panic. You should be asking why, and you should want specific answers, not platitudes.

Red zone (for most specialties): >5–7% annual, or clearly >15% total over recent years

This is the territory where “bad luck” is statistically implausible.

Let us quantify:

- 7% annual attrition over a 3‑year residency: completion ≈ (0.93)³ ≈ 80%.

That means 1 in 5 residents who start there does not graduate there. - For a 5‑year program with 7% annual loss: completion ≈ 0.93⁵ ≈ 69%.

31 out of 100. Gone.

Once you get near:

- ≥10% of residents leaving over a rolling 5‑year window in IM / peds / FM

- ≥15–20% leaving over a rolling 5‑year window in psych / OB‑GYN

- ≥25–30% leaving over a rolling 5‑year window in surgery

…you are in clear red‑flag territory, unless the program can give a very specific and credible story (“department split into two programs and half the residents technically ‘transferred’ to the new ACGME ID” is one of the rare honest examples).

Double‑digit per‑year attrition? That is not a red flag. That is a hazard sign.

5. How to actually estimate a program’s attrition from the outside

You will not get a nice clean table from ACGME labeled “Program X: 8.3% annual attrition.” You have to approximate.

Here is how I would approach it like an analyst.

Step 1: Use class headcount consistency

On interview day or website, note:

- Number of residents per PGY year

- How long the program is (3 vs 4 vs 5+ years)

A stable categorical program should have roughly equal class sizes across PGY levels. If they say “we have 14 PGY‑1s, 12 PGY‑2s, 9 PGY‑3s,” you already see the leak.

Now, compare what they say:

- “We take 14 categorical positions per year.”

With what you see:

- “Our current residents: PGY‑1: 14, PGY‑2: 11, PGY‑3: 10.”

That implies that in the cohort which started with 14, only 11 are still there by PGY‑2 (21% loss of that class), and 10 by PGY‑3 (29% lost). Even if 1–2 were added as transfers, the signal is clear.

Step 2: Cross‑check against historical photos / rosters

Program websites and social media are a gold mine.

Look at a class photo from 3–4 years ago. Count the faces. Then see how many of those people appear in graduation photos or current “alumni” lists.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Starting Class | 14 |

| PGY-2 Remaining | 11 |

| PGY-3 Graduated | 10 |

If a 14‑person class ends with 10 graduates:

- Total attrition for that class = 4/14 ≈ 29%.

- Equivalent constant annual attrition ≈ 11% per year over 3 years.

You do not need perfect precision. You just need enough to categorize the program into green/yellow/red.

Step 3: Ask directly during interviews (and push past the spin)

Questions I have seen work:

- “In the last 5 years, of all categorical residents who started, how many did not finish here?”

- “How many residents have left the program in the last 3 years, and what were the reasons?”

- “Is there anyone who transferred out or changed specialties during that time?”

If they give vague language like “a few people for personal reasons,” ask for approximate counts: “Would you say that is like 1–2 out of 40, or more like 5–6?”

Programs that are healthy and self‑aware will answer this cleanly and usually with names and actual stories (de‑identified, obviously). Unhealthy programs become evasive or defensive.

6. Specialty differences: what is “normal” in your field?

You cannot judge general surgery with family medicine benchmarks. The baseline is different.

Here is a rough comparative map:

| Specialty Category | Typical Pattern | Alarm Threshold (Total Over Program) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Care (IM, FM, Peds) | Low; most finish | >10–12% |

| Psychiatry | Moderate; some early switching | >15–18% |

| OB/GYN | Moderate–high | >15–20% |

| General Surgery | High baseline | >25–30% |

Two key realities:

- Surgical fields have more switching out early on. Some residents realize they do not want that lifestyle. A few percent per year, especially PGY‑1, is unsurprising. Double‑digits, sustained, is not.

- Psych has been undergoing rapid growth and changing applicant profiles. There is some noise. But well‑run programs still have low teen or single‑digit attrition across cohorts.

So calibrate your alarm threshold by field, but do not let anyone convince you that 30% of a class disappearing is just “people finding their path.” That is glossy language for a broken system.

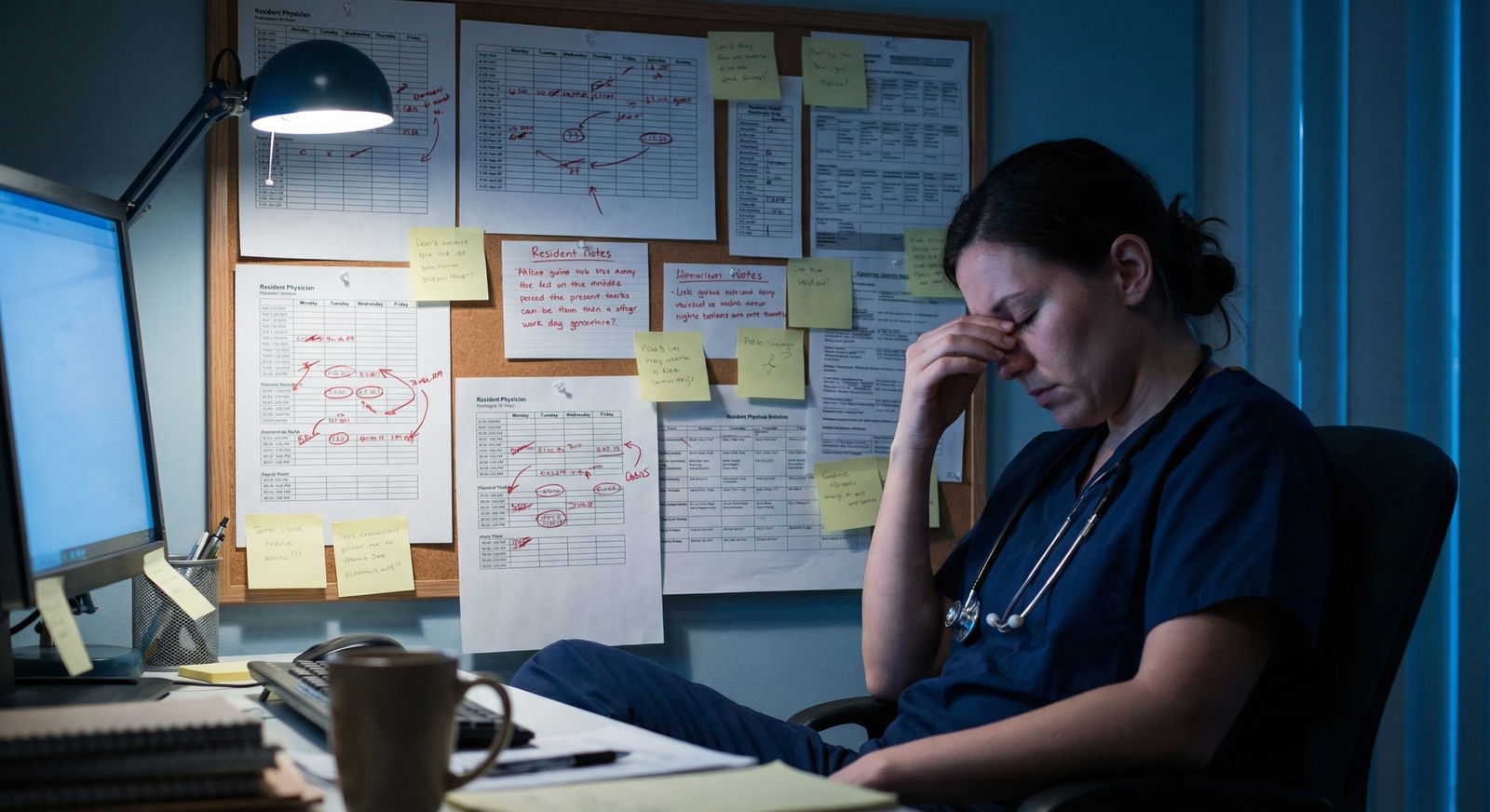

7. What high attrition usually signals underneath

You are not afraid of the number; you are afraid of what the number represents.

From residents I have worked with and program reviews I have seen, chronic high attrition (>15–20% cohort loss) is usually downstream of one or more of these:

- Toxic culture or abusive leadership

- Chaotic scheduling, unsafe workload, chronic violation of duty‑hours “off the books”

- Poor remediation and feedback structure—residents only find out they are “in trouble” when a contract is not renewed

- Financial or institutional instability (mergers, losing key hospitals, losing accreditation)

- Misalignment between recruitment pitch and reality (e.g., they sell “academic with strong research support,” but residents are crushed clinically and get zero protected time)

The data pattern is predictable:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Culture/Leadership | 35 |

| Workload/Burnout | 25 |

| Academic/Performance Issues | 15 |

| Program Instability | 15 |

| Other Personal Factors | 10 |

Rough ballpark from conversations and surveys: roughly a third is culture, another quarter is workload‑burnout, and the rest is a mix of academic and life reasons. Personal catastrophe exists, but it does not drive double‑digit attrition rates by itself.

So when a PD says “we had some personal issues, but we are a family,” and you are simultaneously seeing 4–5 residents missing per class relative to the match list, the story and the data do not match.

8. How applicants should use attrition data in decisions

You are not running a meta‑analysis; you are choosing where you will spend the next 3–7 years of your life.

Here is how to translate all this into a decision framework.

1. Pre‑interview filter

If you can glean that a program has lost:

- More than 15% of its residents across recent cohorts (for IM, peds, FM, psych), or

- More than 25% for surgery/OB‑GYN,

…drop it lower on your rank list right away unless there is a compelling countervailing factor (e.g., you absolutely must be in that specific city and your alternatives are worse).

2. On interview day: triangulate signals

Combine:

- Resident headcounts by PGY

- Tone and candor of resident discussions (“We had a couple people leave, but leadership handled it well” vs awkward silence)

- Program leadership transparency about departures

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Check class sizes by PGY |

| Step 2 | Low concern |

| Step 3 | Ask about departures |

| Step 4 | Moderate concern - decide on fit |

| Step 5 | High concern - move down rank list |

| Step 6 | Numbers consistent? |

| Step 7 | Clear, specific answers? |

If multiple residents independently hint that “a lot of people left last year” and leadership offers no coherent explanation, that is a strong negative data point.

3. Ranking: use attrition as a tiebreaker or veto

Two programs look similar on paper. One has stable classes and graduates essentially everyone; the other has clear holes in its PGY‑2 and PGY‑3 rosters.

The rational choice is obvious. Even if the “riskier” program is more prestigious, the expected value of your training (and sanity) is higher in the stable one.

At the extreme: a program with ongoing, unexplained double‑digit attrition should usually fall off your rank list entirely. You are not a beta tester for their culture overhaul.

9. Where the field is heading: transparency and metrics

Attrition is finally starting to get the attention it deserves as an objective quality marker.

Several trends you should expect:

- More programs tracking “completion rate” internally as a key performance metric.

- Specialty boards and ACGME potentially using persistent high attrition as a trigger for focused site visits.

- Applicants informally compiling attrition anecdotes online—less precise, but the pattern is clear once enough people talk.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| 2018 | 10 |

| 2020 | 20 |

| 2022 | 35 |

| 2024 | 50 |

| 2026 | 70 |

Those numbers are arbitrary but represent the trend I see: awareness and informal reporting are ramping up fast. Formal reporting will lag, but it is heading in the same direction.

Eventually, you should expect something like board pass rates: public, standardized, and impossible to spin. We are not there yet.

Until that happens, you have to do your own homework.

10. A quick heuristic checklist you can actually use

If you want a compact rule‑of‑thumb, here is the data‑driven version I give students:

Count residents per PGY from website or interview.

If any PGY year has ≥20–25% fewer residents than the incoming class size, mark as at least yellow, maybe red.

Ask directly: “How many residents have left in the last 5 years?”

If the total across those cohorts approaches or exceeds:

- 10–12% for IM / peds / FM, or

- 15–20% for psych / OB‑GYN, or

- 25–30% for surgery,

…and there is no clear, coherent story, you are looking at a program with structural problems.

The important part: this is not about being risk‑averse. It is about recognizing that if 20–30% of people like you do not finish at a given program, that is not a reasonable gamble when comparably competitive programs exist with 95%+ completion.

FAQ

1. Is any attrition always a red flag, or is some level acceptable?

Some attrition is inevitable. People have health crises, family emergencies, immigration issues, or realize that they truly want a different specialty. In most stable programs, that translates to maybe 0–2 residents per 60–80 total residents over a few years. So a total attrition under ~5% across a cohort is not worrisome by itself. You start worrying when departures become a pattern—multiple people from consecutive classes, or whole PGY groups that are noticeably smaller than the incoming classes.

2. What if a program claims all attrition was “voluntary”?

From a risk perspective, “voluntary” is often a euphemism. Residents rarely wake up and abruptly quit a reasonably supportive program. They leave after prolonged stress, feeling unsupported, or being told implicitly or explicitly that they are not wanted. Whether the paperwork says “resignation” or “non‑renewal” does not change your lived risk. If the absolute number of people leaving is high, the voluntary/involuntary labeling does not rescue the program’s profile.

3. Are small programs allowed some leeway because one loss skews the percentage?

Percentages in small denominators do swing more wildly. A 4‑resident class losing 1 person is 25% attrition; that sounds awful. This is where you look at multi‑year patterns, not a single class. If a small rural FM program loses 1 resident in 10 years, it is not a red flag. If it loses 1 almost every year, it is. So you smooth the percentage across multiple cohorts: how many residents entered over 5–7 years, and how many of those finished there. The law of large numbers starts to kick in even for small programs when you widen the window.

4. Should I ever rank a high‑attrition program highly if it is in my dream city?

You can, but go in with clear eyes about the trade‑off. High attrition means meaningfully higher odds of severe burnout, conflict, or needing to transfer. If location is non‑negotiable for personal reasons, you might accept that risk consciously and prepare backup strategies (mentors at other institutions, aggressive self‑monitoring for burnout, early networking for potential transfers). But from a purely rational, data‑driven standpoint, a program with stable completion in a less desirable city typically gives you a safer, more predictable career trajectory.

Key points:

- Once true attrition creeps much above 5–7% per year (or 15–20% total over training), the probability that you will not finish there becomes uncomfortably high.

- You can approximate attrition with simple headcounts by PGY and honest questions on interview day; big gaps in class sizes rarely lie.

- Chronic high attrition is not random; it almost always reflects deeper program dysfunction. Treat it as a major red flag when building your rank list.