Most premeds walk into their first operating room shadowing experience dangerously underprepared.

Not because they lack interest or intelligence, but because nobody has ever walked them step-by-step through what safe, appropriate OR behavior actually looks like.

Let me fix that.

This is a concrete, stepwise etiquette and safety primer for shadowing in the operating room—aimed squarely at premeds and early medical students who do not want to be “that” observer everyone remembers for the wrong reasons.

1. Understanding the OR Ecosystem Before You Step Inside

The operating room is not just “another place to shadow.” It is a high‑risk, tightly choreographed environment where one careless move can:

- Contaminate a sterile field

- Delay or complicate a case

- Put a patient at risk

- Burn your professional reputation in seconds

(See also: Using Shadowing to Learn Clinical Decision‑Making: A Case‑Based Approach for more insights.)

So your first mental shift: you are entering their workspace, not a teaching lab built for you.

The Core OR Hierarchy

You must know who’s who and who you answer to:

- Attending surgeon – captain of the surgical ship

- Anesthesiologist / CRNA – in charge of airway, hemodynamics, and anesthesia management

- Scrub nurse / scrub tech – maintains the sterile field; hands instruments; fiercely protective of sterility

- Circulating nurse – “moves around,” obtains supplies, manages documentation, positions equipment

- Residents / fellows / physician assistants – assist the surgeon, perform portions of the procedure

- You, the observer – a guest; lowest on the hierarchy, no clinical responsibilities

Clinical authority goes by expertise and role, not by who invited you. You are expected to follow directions from any OR staff member, especially scrub and circulating nurses.

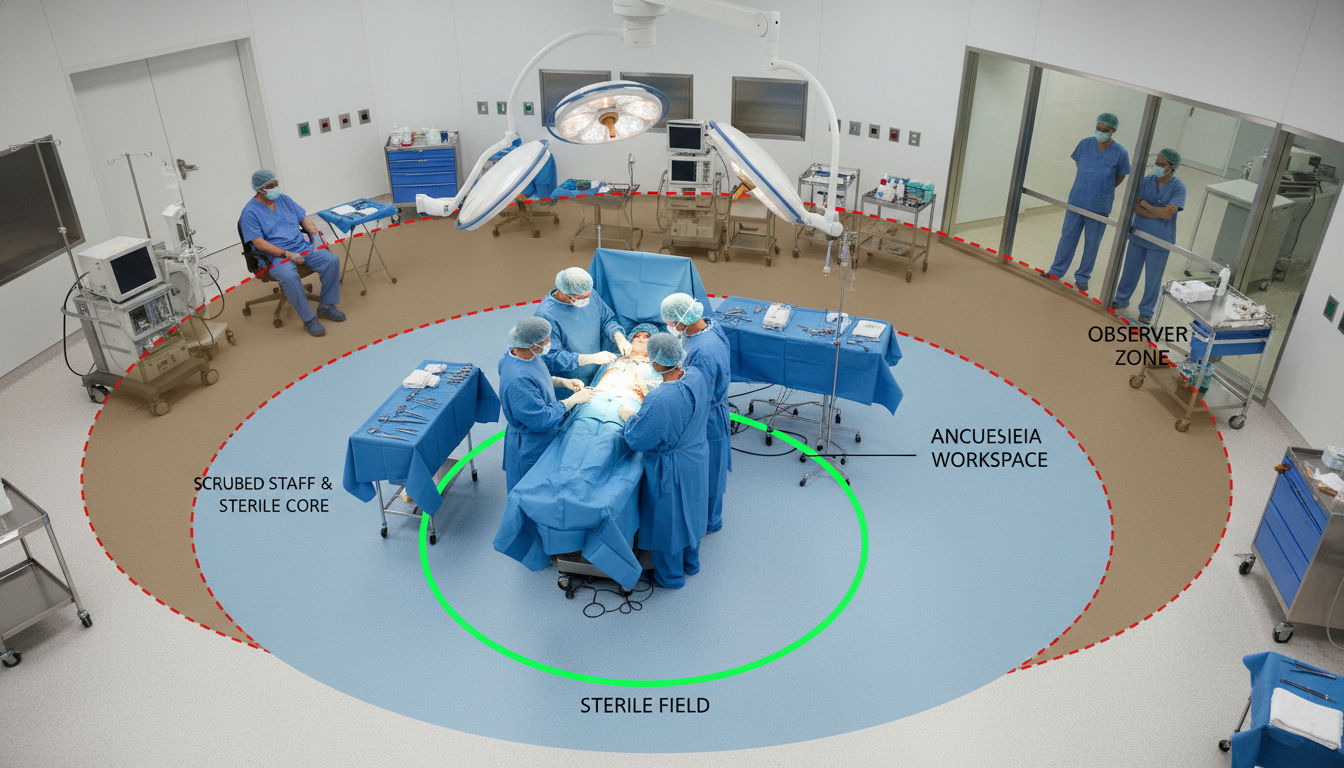

Sterile Versus Non‑Sterile Zones

Conceptually:

- Sterile people: scrubbed surgeon, scrubbed assistant, scrub nurse/tech

- Sterile objects: instrument tables, draped patient, front of sterile gowns, gloved hands

- Non‑sterile people: you, anesthesia providers, circulating nurse, observers

- Non‑sterile objects: anesthesia machines, computer workstations, door handles, carts away from sterile field

Write this into your brain now: If you are shadowing, you are non‑sterile and must stay out of sterile zones. Period.

2. Pre‑OR Preparation: What to Do Before the Case

Your OR etiquette starts long before you see blue drapes.

2.1 Administrative and Legal Must‑Haves

You must clarify:

- Institutional rules: Some hospitals require formal observer programs, HIPAA modules, immunization records (TB, hepatitis B, COVID, etc.).

- Consent: In many institutions, patients consent to “learners” being present. In others, an extra shadowing consent is needed. If a patient declines, you do not go in that room. No discussion.

- Badging: Wear an ID badge at all times, visible above the waist. If there is a “Visitor” or “Observer” badge, use it.

If you gloss over any of these, you are placing the surgeon and the institution at medicolegal risk.

2.2 What to Wear and Bring

Base clothing:

- Plain, clean clothes if the facility provides scrubs (most academic centers do)

- Avoid jeans, leggings that may show under scrubs, noisy jewelry, or anything flashy

In the OR you will typically wear:

- Hospital-issued scrubs (do not wear them from home if the hospital prohibits this)

- Surgical cap / bouffant covering all hair

- Mask (procedure mask or N95, depending on local policy)

- Shoe covers (if required by that institution)

No:

- Open‑toed shoes

- Long dangling earrings, bracelets, watches that can touch surfaces

- Strong perfume/cologne

What to bring:

- Small notepad and pen (kept in a pocket, never above sterile field)

- Minimal valuables; OR lockers are not guaranteed

- Your phone on silent; use only when explicitly appropriate and never near the sterile field

2.3 Pre‑Case Briefing: What To Ask

Before the first case, ask the surgeon or OR contact:

- “Where should I stand to stay out of the way?”

- “Is there anything in this case that tends to be especially sensitive or high‑risk?”

- “Are you comfortable with me asking questions, and if so, when?”

This signals two things: respect for workflow and awareness of safety. Surgeons and nurses notice this.

3. Entering the OR: The First Ten Minutes

The first ten minutes set the tone for your entire day.

3.1 Sequence for Entering Correctly

Change into scrubs

- Use the designated locker room.

- Remove outside coats/jackets.

Put on OR attire before entering the core OR area

- Hair cover first (no hair hanging out the back)

- Mask on properly covering nose and mouth

- Shoe covers if used in that hospital

Perform hand hygiene

- Regular hand washing or alcohol sanitizer. You are not scrubbing for surgery, but your hands must be clean.

Enter the OR before the patient arrives or before draping, when possible

This lets you orient yourself before sterility is fully established. If you come in mid‑case, you must be even more cautious not to brush against sterile fields on your way in.

3.2 Immediate Etiquette on Entry

On entering, do the following in order:

Pause inside the door. Let your eyes adjust and quickly scan the room for:

- The draped patient

- Draped instrument tables

- The scrubbed team

- Anesthesia area

Make eye contact with the circulating nurse. Quietly say:

- “Good morning, I am [Name], premed/med student shadowing Dr. [X] today. Where is a good place for me to stand that will not be in the way?”

Stand in the spot they indicate and stay put at first. Do not migrate around the OR until you fully grasp the layout.

3.3 Where You Should and Should Not Stand

DO:

- Stand near the foot of the bed or on the side opposite the main operative team, as directed

- Keep your back to the wall when moving behind people

- Give wide berth (at least 1–2 feet) around sterile tables and Mayo stands

DO NOT:

- Walk between the scrubbed team and the instrument tables

- Cross between the anesthesia provider and the patient’s head

- Lean on any table that has a blue drape

If you are not sure whether something is sterile? Assume it is and keep your distance.

4. Sterility and Safety: Non‑Negotiable Rules

This is where many first‑time observers make mistakes. You will not.

4.1 The One‑Sentence Rule of Sterility

If it is blue and near the surgical field, do not touch it or reach over it.

That includes:

- Blue drapes on the patient

- Blue‑covered instrument tables

- The front of any sterile gown

- Any sterile tray or Mayo stand

Assume that your entire body is contaminated relative to those areas.

4.2 Specific Sterility Pitfalls to Avoid

You must not:

- Reach over a sterile field to grab something

- Walk between two sterile zones (e.g., between scrubbed surgeon and instrument table)

- Brush against the back of a scrubbed person’s gown while squeezing behind them

If somebody says “Watch the sterility” or “You’re too close,” back away immediately and apologize once, succinctly:

“Sorry about that, I will give more space.”

Do not over‑explain. Do not argue. Just correct your position.

4.3 Infection Prevention: Your Responsibilities

You are not sterile, but you can still reduce infection risk by:

- Keeping mask over nose and mouth at all times

- Avoiding touching your mask or face during the case

- Performing hand hygiene if you leave and re‑enter the OR

- Staying away from any open trays or implant sets

If you must cough or sneeze, turn away from the field and step back, arm over mouth, without removing your mask.

4.4 Safety Around Equipment and Radiation

Beyond sterility, there is physical safety:

- Cords and lines: Do not step on cords, IV lines, or foot pedals. These often control electrocautery, suction, or other critical equipment.

- Sharp hazards: If a sharp is dropped or an instrument falls, do not pick it up. Alert the nearest staff member.

- Radiation (C‑arm, fluoroscopy):

- If radiation is used, you may need a lead apron and thyroid shield.

- If you are not wearing lead, step far back or out of the room when you hear “X‑ray” or “Fluoro on.”

- Fire / cautery: Be aware that electrocautery can cause burns. Do not lean into cables or paddles.

If you ever feel lightheaded, overheated, or unwell, tell the circulating nurse quietly and step out. Fainting onto a sterile field is memorable for all the wrong reasons.

5. Intraoperative Behavior: How to Act During the Case

What you say, how you move, and when you speak matter.

5.1 Baseline Behavior Expectations

- Be quiet by default. OR noise levels are controlled; casual chatter is not appreciated in critical moments.

- Hands position: Fold them in front of you or keep them at your sides. It sounds trivial, but fidgeting or putting hands on surfaces increases contamination risk.

- Eyes forward: Watch the field or monitors, not your phone. Your presence should clearly be for learning.

If music is playing and the mood is light, you still need to read the room. Residents and nurses may chat comfortably, but their baseline comfort does not necessarily extend to you.

5.2 When and How to Ask Questions

Questions can be welcome, but timing is everything.

Good times to ask:

- Before incision

- During slower or repetitive parts of the case (suturing, hemostasis)

- When the surgeon or resident explicitly invites questions

Bad times to ask:

- During induction or emergence from anesthesia

- During critical steps: clamping vessels, dissecting near vital structures, placing central lines

- When alarms are sounding or staff voices suddenly sharpen

How to ask:

- Keep it concise: “Dr. Lee, is now an okay time for a quick question?”

- If yes, ask one focused question, not three tangential ones.

- Do not ask anything that could be construed as criticism of technique or decision‑making.

Example of a good question:

“Could you explain what structure you are identifying here on the monitor?”

Avoid:

“Why did you choose this approach instead of [alternative]?” (Unless the surgeon invites that level of discussion.)

5.3 Protecting Patient Privacy and Dignity

Even in the OR, privacy and respect remain central.

- Do not refer to the patient by full name when speaking; use “the patient” or first name only if the team does.

- Never comment on non‑medical features of the patient (tattoos, body habitus, etc.).

- Phones: no photos, no recordings, no social media updates about “cool cases.” That is a fast track to being barred from the OR, possibly school discipline, and real HIPAA implications.

After the case, never share identifiable details of what you saw outside appropriate educational contexts.

6. Touching Anything: What You May and May Not Handle

Many observers are unsure what is safe to touch. The default is: touch nothing unless explicitly invited.

6.1 Things You Generally May Touch

If not restricted by local policy:

- Door handles and non‑sterile carts

- Computer workstation keyboard or mouse, but only if:

- A staff member instructs you to use it, and

- Your hands are clean, and

- You step away from sterile areas to do so

- Chairs or stools in the observer area

6.2 Things You Must Not Touch

- Any part of the draped patient

- Blue‑draped instrument tables

- Sterile gowns or gloves

- Any instrument set, even if it looks “unused”

- Anesthesia equipment unless explicitly asked by anesthesia staff

If someone offers you a specimen container or something similar, clarify:

“Is this non‑sterile and okay for me to handle?”

6.3 When Surgeons Offer Closer Involvement

Occasionally, a surgeon might say:

- “Come stand closer so you can see this.”

- “Put on some clean gloves and feel this tissue.”

Two rules:

- Only move where directed, and keep your body away from sterile zones.

- If they want you to touch anything near the field, they will define how; do not take initiative yourself.

It is entirely appropriate to say, “I want to make sure I do not break sterility—can you show me where is safe to stand?”

7. Handling Common Awkward Scenarios

These are the real situations that derail many first OR experiences.

7.1 Feeling Dizzy or Faint

This is common in first‑timers. Heat, standing still, smells of cautery, and visual stimuli all contribute.

Warning signs:

- Nausea

- Sweating under your mask

- Tunnel vision or grey‑out

What to do:

- Quietly tell the circulating nurse: “I am feeling a bit lightheaded. I am going to step out for a moment.”

- Step out before you collapse.

- Sit down in the hallway or break area. Drink water, eat something if allowed, cool yourself.

Do not try to “tough it out.” Passing out onto a sterile field is a major incident.

7.2 Being Corrected or Scolded

At some point you may:

- Step too close to a sterile field

- Speak at the wrong time

- Stand in front of an important monitor

If staff correct you firmly, accept it. Professional OR culture can be blunt.

Proper response:

“Understood, thank you” or “Yes, I will move, thank you.”

Do not get defensive. Learn and move on.

7.3 Being Asked a Question You Do Not Know

Some surgeons enjoy “pimping” (rapid questioning). As a premed, you are not expected to know detailed anatomy. You are expected to be honest.

If you do not know:

- “I am not sure of the answer, but I would like to read about it after the case.”

Then actually read about it. If you see them again, referencing that prior question shows growth and seriousness.

7.4 Witnessing Something Disturbing

You may see:

- Large amounts of blood

- Unexpected complications

- Emotional conversations or bad outcomes

If you feel shaken, speak privately to the surgeon afterwards or to a trusted mentor. Processing these experiences is part of professional formation, not a sign of weakness.

8. Exiting the OR and Post‑Case Professionalism

How you leave matters almost as much as how you enter.

8.1 Proper Timing to Leave

You should not:

- Disappear mid‑case without informing anyone

- Walk out right at a critical moment

If you must leave early:

- Choose a non‑critical period (e.g., during closure or dressing application).

- Quietly let the circulating nurse or a resident know: “I need to step out due to [class / prior commitment / not feeling well]. Thank you for having me.”

If you are staying the whole case, you can:

- Leave after dressings are placed and the drapes are removed, or

- After the patient exits the room, depending on how the team runs their room turnover

8.2 De‑gowning / De‑masking

General rules:

- Remove gloves (if you ever wore non‑sterile exam gloves) and discard appropriately.

- Remove mask and cap in designated areas when you are truly done with the OR for a while, or per hospital policy. Some institutions want masks worn in the OR corridor.

- Perform hand hygiene when leaving the OR area.

8.3 Post‑Case Debrief and Professional Courtesy

When appropriate, approach the surgeon after the case, but:

- Not while they are still charting intensely

- Not while they are dealing with a complication‑related phone call

Ideal moment: walking between cases or after they have finished dictating.

Say something along the lines of:

- “Thank you for letting me observe your case today. I learned a lot watching how you handled [specific aspect].”

If you want to come back:

- “If you are open to it, I would appreciate the chance to shadow again on another operative day.”

This shows specific engagement, not just generic flattery.

9. Long‑Term Strategy: Turning Shadowing into Real Learning

Shadowing in the OR is more than just “watching surgery.” With a bit of structure, you can convert scattered impressions into meaningful preparation for medical training.

9.1 Before Each Shadowing Day

- Read a short overview of one or two procedures you might see (appendectomy, cholecystectomy, C‑section, hip replacement). Focus on:

- Basic anatomy

- Indications

- Major steps

- Prepare 2–3 thoughtful, procedure‑related questions in your notebook. Use them only if timing and tone are appropriate.

9.2 During the Case

In your mind, track:

- Patient’s pre‑op problem → operative strategy → intra‑op decisions → immediate post‑op plan.

- The coordination between surgeon, anesthesia, and nursing: how does the communication flow?

- Moments of tension: what triggered them, and how were they managed?

You are not just learning surgery. You are learning systems, teamwork, and real‑time decision-making.

9.3 After the Day

As soon as you are home, jot down:

- 3 things you learned

- 1 thing you did well behavior‑wise

- 1 thing you will do differently next time (e.g., “stand further from instrument tables,” “ask about lead apron earlier before fluoro cases”)

This micro‑reflection will accelerate your growth much more than passively attending dozens of OR days.

FAQ (Exactly 5 Questions)

1. As a premed, am I allowed to scrub into surgery and stand right next to the field?

Usually no. Most hospitals restrict scrubbing to individuals with defined roles in patient care (surgeons, trainees, scrub techs). As a premed observer, you will almost always remain non‑sterile. Rare exceptions can occur in very small hospitals or with specific permissions, but you should never request to scrub in; if it ever becomes appropriate, the surgeon will offer.

2. What should I do if the surgeon or staff start joking in ways that seem unprofessional?

Maintain a neutral, professional demeanor. Do not join in questionable humor about patients, colleagues, or sensitive topics. You are there as a guest and trainee; engaging in unprofessional banter can reflect poorly on you even if others seem comfortable with it. Your safest posture is respectful attentiveness.

3. Is it acceptable to step out of a long case to use the restroom or eat something?

Yes, but timing and communication matter. Wait for a non‑critical part of the case, then quietly inform the circulating nurse that you need to step out briefly. Do not vanish without letting anyone know, and do not re‑enter during obviously high‑stakes moments (induction, major dissection, critical vascular steps).

4. Can I record parts of the surgery on my phone if I avoid showing the patient’s face or name?

No. Recording in the OR for personal use is almost universally prohibited, regardless of whether identifiers are visible. Institutional policies, medicolegal risk, and HIPAA all strongly restrict image and video capture. Assume that any photography or recording is off‑limits unless explicitly initiated and supervised by the clinical team under institutional protocols.

5. How many OR shadowing hours are “enough” for medical school applications?

There is no magic number, but 10–20 focused OR hours, embedded within a broader set of clinical experiences, is usually sufficient to demonstrate exposure to surgical practice. Admissions committees care far more about how thoughtfully you can reflect on what you observed—teamwork, patient vulnerability, ethical moments—than about whether you logged 15 vs. 50 hours in the OR.

Key points to carry forward:

- The OR is a high‑risk, tightly regulated environment where your primary role is to not interfere with safety or sterility.

- Sterile zones are off‑limits; when in doubt, do not touch and do not approach.

- Thoughtful preparation, quiet situational awareness, and brief, well‑timed questions will mark you as the rare premed who truly understands how to be in the operating room.