What if every single one of your letters of recommendation says the exact same bland nonsense?

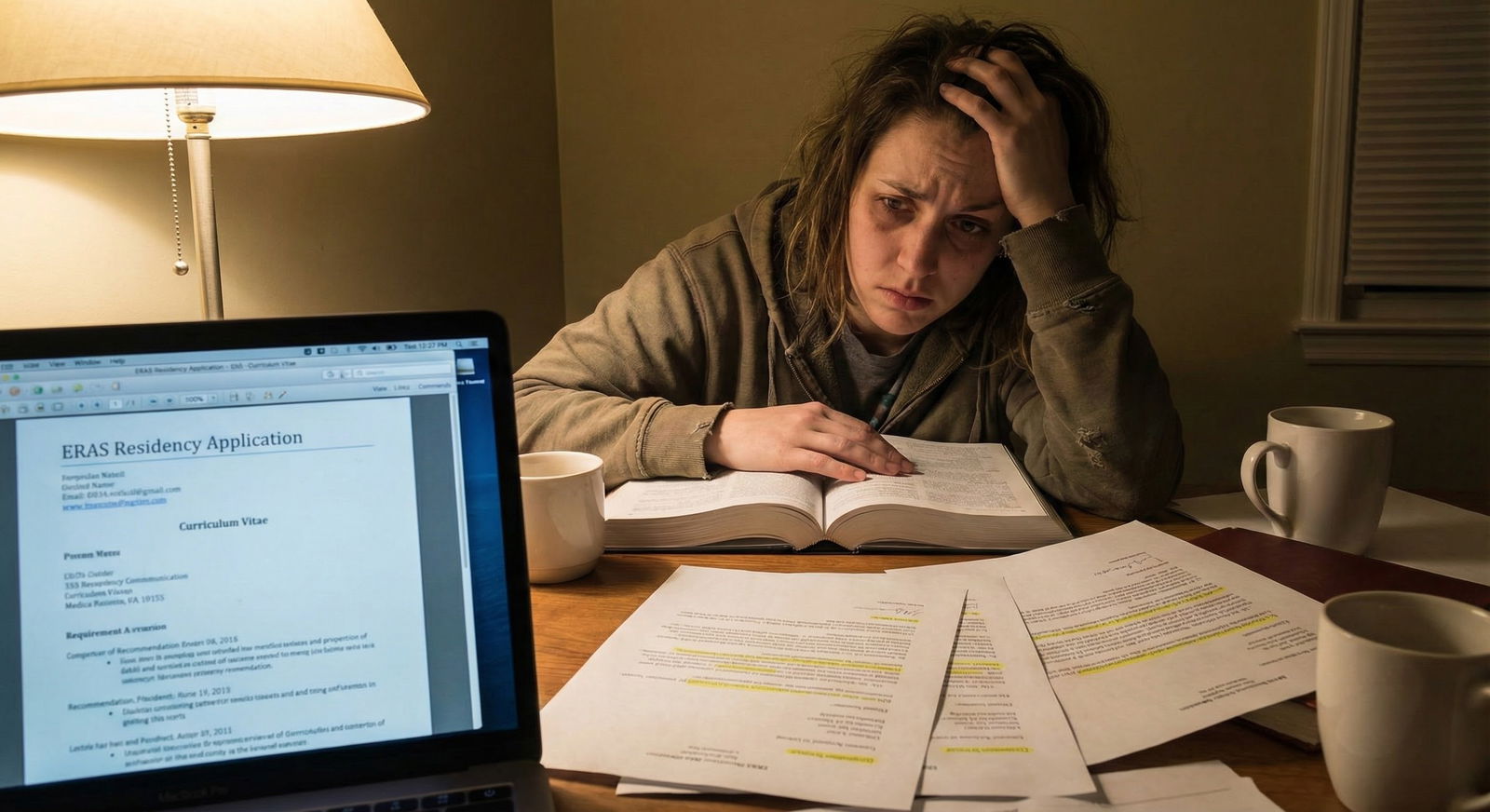

That’s the nightmare, right? You open ERAS in September, your applications are ready, you’ve killed yourself on Step 2, your personal statement has been rewritten 14 times… and then your LORs are all basically: “Hardworking. Team player. Pleasure to work with.” Zero specifics. No “top 10%,” no cases, no ownership, nothing that sounds like they even remember you.

Let me be blunt: generic letters suck. Programs can smell them from space. And yes, they can drag you down, especially in competitive specialties or if your metrics are borderline.

But. You’re not powerless here, and you don’t have to wait until September to find out you’re screwed.

Let’s talk backup plans you can start before ERAS locks and you’re trapped.

Step 1: Reality check – how bad is “generic,” really?

Before we go full catastrophe mode, you need a rough sense of where LORs sit in the bigger picture.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| LORs | 80 |

| Step Scores | 85 |

| MSPE | 70 |

| Clerkship Grades | 75 |

| Personal Statement | 40 |

This isn’t exact science, but it’s how a lot of PDs think:

- LORs are heavily weighted, especially in fields like IM, EM, Gen Surg, Ortho, Derm, etc.

- A good letter can really help.

- A generic one doesn’t necessarily kill you. It just doesn’t help. It’s “neutral” at best.

The real problem isn’t one generic letter. It’s if:

- All of them sound the same.

- None mention concrete examples or relative ranking.

- They read like the attending barely knows you.

Programs read hundreds of ERAS packets. When they hit three basically interchangeable letters, it creates this vague impression: “Was this student ever really outstanding to anyone?”

That’s the anxiety talking, and also… it’s not totally wrong.

So your job now: reduce the odds that everything ends up generic and build insurance if it does.

Step 2: Figure out your risk level now, not in September

You can’t see the letters, sure. But you can read the room.

Here are three categories I see all the time:

| Risk Level | Common Scenario |

|---|---|

| Low | You worked very closely with 2–3 attendings who gave you clear, strong verbal feedback |

| Medium | You rotated with many attendings, one-on-one time was limited, feedback was “solid” but vague |

| High | You barely worked directly with letter writers, huge teams, minimal face time |

If you’re high risk, you should be in “active damage control” mode now.

Ask yourself, honestly:

- Did anyone ever say anything like “I’d be happy to write you a strong letter”?

- Did you get end-of-rotation comments that included phrases like “one of the best students I’ve worked with this year,” “outstanding,” “top tier,” etc.?

- Or was it all: “You did well. Keep doing what you’re doing”?

If you’re mostly in the third bucket… yeah, worry a little. Then do something about it.

Step 3: Stop being passive: shape your letters before they’re even written

This is the part med students avoid because it feels awkward. It’s also the part that actually moves the needle.

When you ask for a letter, how you ask matters.

Weak ask:

“Hi Dr. Smith, I was wondering if you’d be willing to write me a letter of recommendation for internal medicine residency?”

Result: Sure, they’ll probably say yes. And then write the same bland nonsense they’ve written 50 times.

Stronger ask:

“Dr. Smith, I really enjoyed working with you on wards. I’m applying to internal medicine and I was hoping you’d feel comfortable writing me a strong, personalized letter of recommendation. I’m especially hoping to highlight my work ethic, ability to own patient care, and willingness to go the extra mile. Do you feel you know me well enough to do that?”

This does three things:

- Gives them an out if they’ll only write something generic.

- Plants the idea: “strong” and “personalized.”

- Signals the traits you want them to emphasize.

If they hesitate, stall, or say something like “I can write you a letter, but I don’t know you that well”… you just dodged a generic LOR landmine. That’s not a loss. That’s a win.

Also: send them a short “LOR packet”:

- Your CV

- Your personal statement draft (or at least a paragraph of what you’re going for)

- A one-page “Highlights with Dr. X” document:

- 2–4 cases you worked on with them

- Specific things you did: patient counseling, follow-ups, extra reading, QI project help

- Any feedback they gave you at the time

You’re not “writing your own letter.” You’re jogging their memory. Most attendings appreciate it. And their letters get less generic just because you handed them actual details.

Step 4: Build emergency backup letters before you’re desperate

You need redundancy. Think of LORs like backups of your hard drive. Assume one or two might fail you.

Here’s how to quietly build a safety net:

1. Ask more people than you strictly need

If your specialty wants 3 letters, try to line up 4–5:

- 2 from your chosen specialty (core)

- 1 from another clinical field who really knows you

- 1 from research or a longitudinal mentor

- Maybe 1 department chair / PD style letter if your school does that

You don’t have to use all of them on ERAS for every program. But you’ll have options. If someone is slow, flaky, or you have a bad feeling, you’re not trapped.

2. Diversify the type of relationships

The most generic letters are often:

- From big-name attendings you barely worked with, or

- From people who supervised you for literally 3 days on a huge team

Stronger, less generic letters often come from:

- Longitudinal clinics

- Research mentors you met weekly for months

- Hospitalists on busy wards where you ran with them for 4 weeks

So if your current set is all short stints with famous people, that’s a red flag. Start cultivating one or two people who actually know you as a human and not “MS3 who presented chest pain that one time.”

Step 5: What if it’s already late and you suspect your letters are weak?

You’re in that horrible limbo: letters requested, ERAS season close, but no control over what’s actually written.

Here are moves you can still make:

1. Add one more “late but strong” letter

Programs would rather see:

- One strong letter that arrives a bit later

than - Only generic fluff that was uploaded on day one.

If there’s an attending now (or on a current rotation) who knows you well:

- Ask now for a strong, personalized letter.

- Upload it as soon as possible, even if it’s after you’ve already applied.

Programs often revisit files when new letters come in, especially early in the season.

2. Use your personal statement and experiences to fill the “specifics” gap

If your fear is: “My letters don’t show who I am,” then you need your other pieces to do that job.

In your personal statement and ERAS experiences, be:

- Specific: particular patients, real challenges, turning points.

- Concrete: things you changed, improved, took ownership of.

- Honest: if you had a rough year, mention growth, not excuses.

Generic LORs plus generic essays scream “nothing special.”

Generic LORs plus sharp, vivid essays say, “Okay, maybe their letter writers were lazy, but this person clearly did a lot.”

3. Use your MSPE and dean’s office strategically

If you have any control at your school:

- Provide your dean’s office with specific examples and themes you want highlighted.

- If your clinical evals have strong comments, make sure they’re pulled into the MSPE.

The MSPE sometimes ends up being the only place where concrete praise shows up. Don’t waste that.

Step 6: Red flags that a letter might be generic – and what you can still do

Some warning signs:

- You asked very late, after barely talking to them.

- They never gave you direct feedback on your performance.

- They seem disorganized or overcommitted.

- They respond with “Sure, just send me your CV” and no follow-up questions ever.

What you can do:

- Gently check in:

- “I just wanted to follow up and see if you needed any additional information or specific examples from our time working together.”

- Attach your “Highlights with Dr. X” document.

- If they still seem totally detached, don’t rely on that letter as one of your top 2–3.

Also—don’t romanticize big names. A generic letter from a famous surgeon is not better than a specific, detailed, glowing letter from a no-name hospitalist. Programs read content, not just letterhead.

Step 7: Worst-case scenarios (and how bad they really are)

Let’s actually say it out loud. Worst case:

- You end up with 3 letters that are:

- Professional

- Positive-ish

- But bland and nonspecific

What happens?

You’re not automatically doomed. But:

- You lose a big chance to stand out.

- Your application will lean more heavily on:

- Step 2 score

- Clerkship grades

- MSPE comments

- Personal statement

- Interview performance (if you get there)

You’re basically competing with a slightly heavier weight on your ankles. Not impossible. Just harder.

Where it hurts the most:

- Hyper-competitive specialties (Derm, Ortho, ENT, Plastics, etc.)

- Super top-tier academic programs

- When your metrics are border-zone and you needed letters to “explain” or “offset” something

Where you can still be very viable:

- Mid-tier, solid academic and community programs

- Home program where people know you outside the letters

- Programs that value grit, consistency, and being low-drama over shiny hype

And remember: interview day is a massive reset button. A lukewarm letter is not as damaging as coming across as awkward, disinterested, or arrogant in person. Don’t let letter anxiety tank your actual human interactions.

Step 8: Concrete plan from now until ERAS

Let’s turn the anxiety into a checklist.

| Period | Event |

|---|---|

| Early (2-4 months before ERAS) - Identify strong potential writers | 1 |

| Early (2-4 months before ERAS) - Ask for strong, personalized letters | 2 |

| Early (2-4 months before ERAS) - Prepare CV and highlights documents | 3 |

| Mid (1-2 months before ERAS) - Follow up with writers | 4 |

| Mid (1-2 months before ERAS) - Add at least one backup writer | 5 |

| Mid (1-2 months before ERAS) - Refine personal statement and experiences | 6 |

| Late (Final month before ERAS) - Confirm letters uploaded | 7 |

| Late (Final month before ERAS) - Add any strong late letters | 8 |

| Late (Final month before ERAS) - Adjust program list based on perceived strength | 9 |

You don’t need perfect letters to match. You need:

- Enough letters that aren’t bad

- At least one or two that sound genuinely like someone knows and respects you

- The rest of your application pulling its weight

You can still influence that.

Quick comparison: “I did nothing” vs “I took control”

| Aspect | Passive Approach | Proactive Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Number of writers | Exactly required | Extra backups |

| How you asked | “Can you write a letter?” | “Can you write a strong, personalized letter?” |

| Info provided | CV only | CV + personal statement + highlights |

| Risk of all-generic set | High | Much lower |

| Options if one is weak | None | Swap, add late letter, rebalance choices |

You can choose which column you’re in.

FAQ – Exactly 6 Questions

1. Should I ever not use a letter that’s already uploaded to ERAS?

Yes. You don’t have to assign every letter to every program. If you know (or strongly suspect) that one letter is weak, generic, or from someone who didn’t really like you, leave it unused and prioritize stronger ones. Programs don’t see which letters you didn’t send them.

2. Is it okay to ask a writer directly if they can write a “strong” letter?

Not only okay — smart. Say it out loud: “Would you feel comfortable writing me a strong letter of recommendation?” If they hesitate or qualify their response, that’s your warning. You want people who say “Absolutely” without blinking.

3. What if all my strongest relationships are outside my chosen specialty?

That’s not fatal. Ideally you have at least 1–2 letters from your specialty. But a glowing letter from a different specialty who’s known you a long time can be more valuable than a throwaway “solid student” letter from your target field. Use both: a couple of mandatory specialty letters plus at least one “this person actually knows me” letter.

4. How late is too late to add a new letter?

Earlier is better, but adding a strong letter in late September or even October can still help. Many programs keep reviewing files as interview season evolves. Don’t use “it’s already late” as an excuse to do nothing. A strong letter that arrives a few weeks after apps go out is still better than never.

5. Can I ask to read my own letter?

If your institution uses a waiver process (and most do), you’re generally not supposed to read it once you’ve waived your right. Some attendings might voluntarily show you a draft, but you shouldn’t push for it. Instead of trying to see the letter, control what you can: who you ask, how you ask, and what information you give them.

6. If I think my letters are generic, should I apply to fewer or more programs?

More. If letters are a weak point, that’s a reason to over-apply, not under-apply—within reason and budget. Broaden your list: more community programs, more mid-tier academic places, and not just the shiniest names. You’re buying more chances for someone to say, “Yeah, this file is solid enough to interview.”

Open a blank document right now and make a list of 5 possible letter writers: 3 you’ve already asked, and 2 potential backups. Next to each name, write how well they know you (1–10). Anyone under a 7? Plan how you’ll replace them or support them with better info this week.