You are here

You’re in a small conference room on the interview trail. You just finished your polished answer to, “Tell me about a time you had a conflict on the team and how you handled it.”

You think you nailed it. You mentioned “communication,” “active listening,” “patient-centered care.” You even ended with, “and in the end, we all learned a lot from the experience.”

Across from you, the PD nods, smiles politely, scribbles something on the sheet.

You have no idea that what they just wrote was: “Vague. Avoidant. No ownership.”

This is what happens behind closed doors.

I’ve sat in those rooms. I’ve watched the note-taking, the eye contact, the quiet decisions about who is “safe to work with at 2 a.m.” and who is all buzzwords and no substance. And behavioral questions are where candidates expose themselves the most—usually without realizing it.

Let me walk you through how real PDs and faculty actually react to the most common behavioral answers. Not the sanitized version you hear in workshops. The real one.

What PDs Are Actually Scoring When You Talk

Before we get into specific questions, you need to understand the mental checklist in most PDs’ heads.

They’re not thinking, “Did this student use the STAR format beautifully?” They’re thinking things like:

- “Can I trust this person alone on nights with my patients and my nurses?”

- “Will this person create drama, or defuse it?”

- “Is this someone I would want to mentor, or avoid?”

The content of your story matters, but the subtext matters more. Your tone. Who you blame. How you talk about nurses, peers, attendings. How much responsibility you actually take.

I’ve heard PDs say this almost word-for-word: “I don’t care if the story is small. I care if I believe it.”

That’s your bar.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Judgment & Insight | 30 |

| Accountability | 25 |

| Team Fit | 20 |

| Communication Clarity | 15 |

| Buzzword Polish | 10 |

The “Conflict on a Team” Question

This one: “Tell me about a time you had a conflict with a team member and how you handled it.”

You’ve probably practiced it. You probably hate it. But it’s gold for PDs.

The common “safe” answer students give

You: “I usually get along with everyone, but there was one time on my surgery rotation where a fellow student and I had a miscommunication about who was supposed to follow up on a lab. The lab was delayed, and the resident was upset. I realized communication is really important, so I made sure to clarify roles going forward and everything went smoothly after that.”

What you think they’re hearing

“I don’t create drama. I fixed the problem. I value communication. I’m a team player.”

What a PD actually writes on the sheet

I’ve seen variations of these comments:

- “Non-conflict answer. Avoids depth.”

- “No emotional content, no complexity. Feels rehearsed.”

- “Doesn’t show how they respond when things really go wrong.”

They’re thinking: You either have not actually reflected on any real conflict, or you’re too scared to talk about it honestly. Neither is reassuring.

PDs know there’s conflict in med school. Students fight. Residents clash. Attendings yell. When you give them a kindergarten-level “we just had a little miscommunication” story, you sound edited. And if you sound edited, you sound untrustworthy.

The answer that quietly wins the room

Let me give you the kind of answer that gets a different reaction:

You:

“On my medicine sub-I, I worked with another student who was consistently late with notes, and it was starting to fall on me. I was getting frustrated because it made the whole team look disorganized when we rounded. At first I just quietly redid a lot of his work, which honestly made me resentful.

After a couple days, I realized that wasn’t sustainable and I wasn’t being fair by not addressing it directly. I asked him if we could talk after rounds. I told him I was feeling overwhelmed picking up extra work and asked how he was doing with the patient load. He actually shared that he was struggling with time management and felt embarrassed to ask for help.

We ended up making a plan to divide the list more clearly and checked in midday to see how things were going. I also looped in the resident, not to throw him under the bus but to ask if she could help us prioritize tasks. Over the next week, his notes improved and I stopped double-charting everything.

What I learned was that my first instinct—just silently fixing everything—didn’t help anyone. It hid the problem and made me bitter. Having a direct but respectful conversation was uncomfortable, but it’s better than letting frustration build to the point where it hurts the team.”

PD reaction behind closed doors

The notes here look different:

- “Takes ownership of own initial poor strategy.”

- “Shows insight and growth.”

- “Addresses conflict directly but not hostile. Involved resident appropriately.”

After the interview, you’ll hear comments like:

- “That was a real answer. I’d trust this person to talk to a co-intern instead of gossiping to nurses.”

- “They didn’t make themselves the hero. They admitted their first approach was wrong. That’s adult behavior.”

See the pattern? It is not about having some dramatic, perfect resolution story. It is about whether you sound like someone who can have uncomfortable conversations without exploding or disappearing.

The “Tell Me About a Mistake You Made” Trap

This one terrifies people: “Tell me about a time you made a mistake and what you learned from it.”

Most students respond with what PDs jokingly call the “fake mistake” or the “tiny paperwork crime.”

The typical “fake mistake” answer

You:

“On one of my early rotations, I forgot to sign an order and it delayed a medication for a brief time. I was very upset with myself, but I immediately corrected it, apologized to the team, and since then I’ve become very meticulous about triple-checking all my orders. Now I always double-check my work so it never happens again.”

What PDs hear

- “This is a low-stakes, non-threatening story.”

- “They are afraid to talk about real clinical misjudgment.”

- “This could be an integrity issue—they might be hiding something more serious.”

A seasoned PD once turned to me after a string of those answers and said, “If I hear one more unsigned-order story, I’m going to start docking people for it.” He wasn’t joking.

The mistake question is not about perfection. It’s about judgment and honesty. They want to see if you can look at yourself without flinching.

A “real” mistake answer that PDs respect

You:

“On my ICU rotation, I was following a patient with worsening respiratory status. He was more tachypneic in the afternoon, and I remember thinking, ‘He looks more tired,’ but I didn’t push the resident to reassess him right away. I told myself, ‘They’re busy, they know he’s sick.’

By evening, he had decompensated and needed to be emergently intubated. When I went home that night, I kept replaying that moment where I noticed he looked worse but didn’t say anything stronger than, ‘He seems a little more labored.’

I brought it up with my resident the next day, and she told me something that stuck with me: as a student, it’s okay to be wrong, but it’s not okay to be silent. Since then, I’ve made a point that if my gut is really telling me something is off, I speak up clearly—‘I’m concerned he’s deteriorating’—even if I’m not sure I’m right.

I still think about that case when I’m on the fence about escalating concerns. I’d rather be the annoying one who called something early than the quiet one who saw it and said nothing.”

PD notes on this kind of answer

You’ll see:

- “Shows moral seriousness. Gets it.”

- “Understands the emotional weight of near-misses.”

- “Learns the right lesson: speak up, don’t disappear.”

Not, “Oh no, they’re unsafe.” More like, “Good, this one has actually felt the weight of being responsible. They’ll grow.”

The worst thing you can do with this question is dodge. The second worst is catastrophize: we do not need a dramatic “patient died because of me” story delivered with performative guilt. A near-miss or moderate error with clear learning is exactly the zone they’re looking for.

The “Weakness” Question: Where People Accidentally Self-Nuke

“Tell me about one of your weaknesses.”

Faculty hate this question almost as much as you do, but it’s still used because it reveals your insight, your defensiveness, and your BS tolerance in about 20 seconds.

The cliché answers that kill you quietly

You:

“I’m a perfectionist.”

Or:

“I care too much and sometimes I take on too much work because I really want to help the team.”

Faculty reaction? Eye roll. Literally. You’ll see it.

Private comments afterward:

- “Scripted.”

- “No real self-awareness.”

- “Trying to be clever instead of honest.”

And here’s the part people don’t realize: when you give a fake weakness, faculty will go looking for your real weaknesses in your letters and MSPE. They assume you’re hiding something. Often they’re right.

A weakness answer that actually reassures PDs

You:

“Earlier in medical school, I had a tendency to over-explain and fill space when I was anxious presenting to attendings. I’d include too many minor details and then get flustered when they interrupted, which made me look less prepared than I actually was.

On my medicine sub-I, one attending pulled me aside and told me, ‘You have the data, but you’re burying your argument.’ That stung, but it was true. Since then, I’ve been deliberately practicing more structured, concise presentations—writing out one-line assessments for each problem and forcing myself to lead with the headline.

I’m better now, but I still catch myself reverting to the ‘data dump’ when I’m tired or nervous. It’s an ongoing project, but at least now I recognize it in real time and can course-correct.”

Faculty notes:

- “Concrete, believable, and extremely fixable.”

- “Shows coachability and specific strategy for improvement.”

- “Feels like someone who will respond well to feedback.”

Here’s the insider rule: a good weakness is:

- Real but non-fatal

- Concrete and observable

- Paired with a specific, credible plan you’ve already started

You’re not auditioning for sainthood. You’re auditioning for “teachable and self-aware.”

“Tell Me About a Time You Worked With Someone Difficult”

Slightly different from the generic conflict question. This one is specifically about difficult people. Which is where candidates reveal their attitude toward nurses, staff, and hierarchy. PDs pay ruthless attention here.

The answer that sinks you without you realizing

You:

“On one of my rotations, there was a nurse who was always very negative and not very helpful. Whenever I asked for help or clarification, she seemed annoyed and would make comments about students slowing things down. I stayed professional and tried not to let it bother me, and eventually I just focused on working with other nurses who were more receptive.”

You think you sound professional and above the drama. You don’t.

The PD hears: “Talks negatively about nurses. Writes people off instead of trying to improve the relationship. Fragile.”

If you throw nurses or staff under the bus in your story—even if you’re “just telling it like it is”—you’ll get dinged. I’ve watched more than one candidate get torpedoed after an otherwise solid interview because they casually trashed a nurse, coordinator, or another student.

A reframed version that PDs actually respect

You:

“On my ED rotation, there was one nurse who I perceived as very short with me. Early on, when I asked questions, she’d give very brief answers or sigh, and I felt like she didn’t want me around. I caught myself starting to avoid her and only go to other nurses.

After a few shifts, I realized that was making the tension worse. I asked if I could help her with anything at the start of the shift—stocking, grabbing supplies—just to show I wasn’t there only to take. Over time, I learned she was often juggling high-acuity patients and had been burned by students who created more work for her.

Once she saw that I was trying to be useful and not just hover, her tone changed. By the end, she was actually teaching me tricks about IVs and triage that I wouldn’t have picked up otherwise.

That experience taught me that what I perceive as ‘difficult’ is sometimes just ‘overloaded and not sure I’ll be helpful.’ It pushed me to approach those situations with curiosity and humility instead of just labeling someone as negative.”

Now the PD hears:

- “Does not attack character; frames behavior in context.”

- “Starts by owning their own reaction.”

- “Builds bridges instead of quietly stewing.”

Behind closed doors, you’ll hear: “Good. They respect nurses. They get that the ED is under pressure. This person will integrate.”

| Type of Answer | PD Category | Likely Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Vague, buzzword-heavy, no specifics | Scripted / Unreliable | Neutral to negative |

| Honest but catastrophizing, no learning | Risky Insight | Mixed, depends on rest of file |

| Concrete story + clear learning + some vulnerability | High Maturity | Strong positive |

| Blaming others, especially nurses/peers | Red Flag Attitude | Significant negative |

| Fake weaknesses / fake mistakes | Low Self-Awareness | Negative tilt |

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Candidate Answers Question |

| Step 2 | Scripted / Vague → Low trust |

| Step 3 | Blames others → Red flag |

| Step 4 | Stuck pattern → Concern |

| Step 5 | Insightful & coachable → Positive |

| Step 6 | Is story concrete? |

| Step 7 | Takes ownership? |

| Step 8 | Shows growth? |

The “Leadership” Question: Where Overreach Gets Exposed

“Tell me about a time you demonstrated leadership.”

This one sounds like a chance to flex. Students start stacking titles: “I was president of…” “I started a new initiative…” “I led a research team…”

PDs, especially in competitive specialties, are allergic to overinflated leadership stories that are basically “I sent some emails and ordered pizza.”

The overblown leadership answer

You:

“I was president of our school’s internal medicine interest group. We organized multiple events, including faculty panels and lunch talks. I coordinated with many stakeholders and ensured everything ran smoothly. Through this role, I developed my leadership skills by delegating and managing a team.”

Faculty thoughts:

- “Generic. No sense of what they actually did when something went wrong.”

- “Everyone was president of something.”

- “This tells me nothing about what you’re like at 3 a.m. in the hospital.”

Leadership, to a PD, is: what you do when things are messy, people are tired, and something important is on the line. Titles don’t impress them. Behavior does.

A leadership answer that actually lands

You:

“During my sub-I, our team had a run of discharges that kept getting delayed late into the evening. Patients were frustrated, families were angry, and the interns were staying late to finish last-minute paperwork. I noticed that a lot of the delays came from small but predictable issues—late med recs, missing follow-up appointments.

I asked one of the interns if I could try tracking the discharge process for a few patients. Over a week, I kept a handwritten list of every step and timestamp. Patterns emerged: we weren’t starting discharge summaries early, and follow-up appointments were being scheduled too close to actual discharge.

I brought a one-page summary of that to our senior resident and suggested that, as students, we could pre-start discharge summaries on likely-to-leave patients and call clinics earlier in the day under supervision. She liked the idea; we piloted it for a week with three discharges a day. Average discharge time shifted from late afternoon to closer to noon for those patients.

It was a small change, but it taught me that leadership as a student isn’t about authority, it’s about noticing friction and being willing to propose and own a solution, even if it’s unglamorous.”

PD notes:

- “Systems thinking. Initiative without overstepping.”

- “Understand student scope but still made an impact.”

- “This is leadership we can actually use.”

The magic here is simple: you’re showing leadership as useful problem-solving, not as “I had a title on my CV.”

What PDs Say In The Debrief You Never Hear

After you leave, there’s a short, often brutal conversation about you. Let me give you a sample of the real dialogue I’ve heard, specifically about behavioral answers.

Example 1 – candidate with all polished, empty answers:

Faculty 1: “Smart kid, good scores. But every answer felt like it came from a workshop.”

Faculty 2: “Yeah, I couldn’t get a real sense of who they are. Nothing concrete.”

PD: “We have enough high-achieving robots. Unless another interviewer felt strongly, they’re middle of the rank list.”

Example 2 – candidate with one very honest, reflective mistake story:

Faculty 1: “I liked them. Their story about missing a clinical deterioration and owning it felt very real.”

Faculty 2: “Agreed. They didn’t panic, just showed they learned. I’d be comfortable with them on my service.”

PD: “Good. They go into the ‘safe and coachable’ bucket. That’s who we want as interns.”

Example 3 – candidate who complained about a “difficult nurse” in a condescending way:

Faculty 1: “Did you hear how they talked about that nurse? Big red flag.”

Faculty 2: “Yeah. No sense of how they contributed to the tension. Just blame.”

PD: “We’re not taking someone who’s going to create nurse-physician drama. They go low or off.”

That’s the game behind closed doors. Your behavioral answers are not graded like essay questions. They are used as x-rays: Where are the fractures in your maturity, insight, and attitude?

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Blaming nurses/staff | 30 |

| No real mistake admitted | 25 |

| Vague conflict story | 20 |

| Fake weakness | 15 |

| Overblown leadership | 10 |

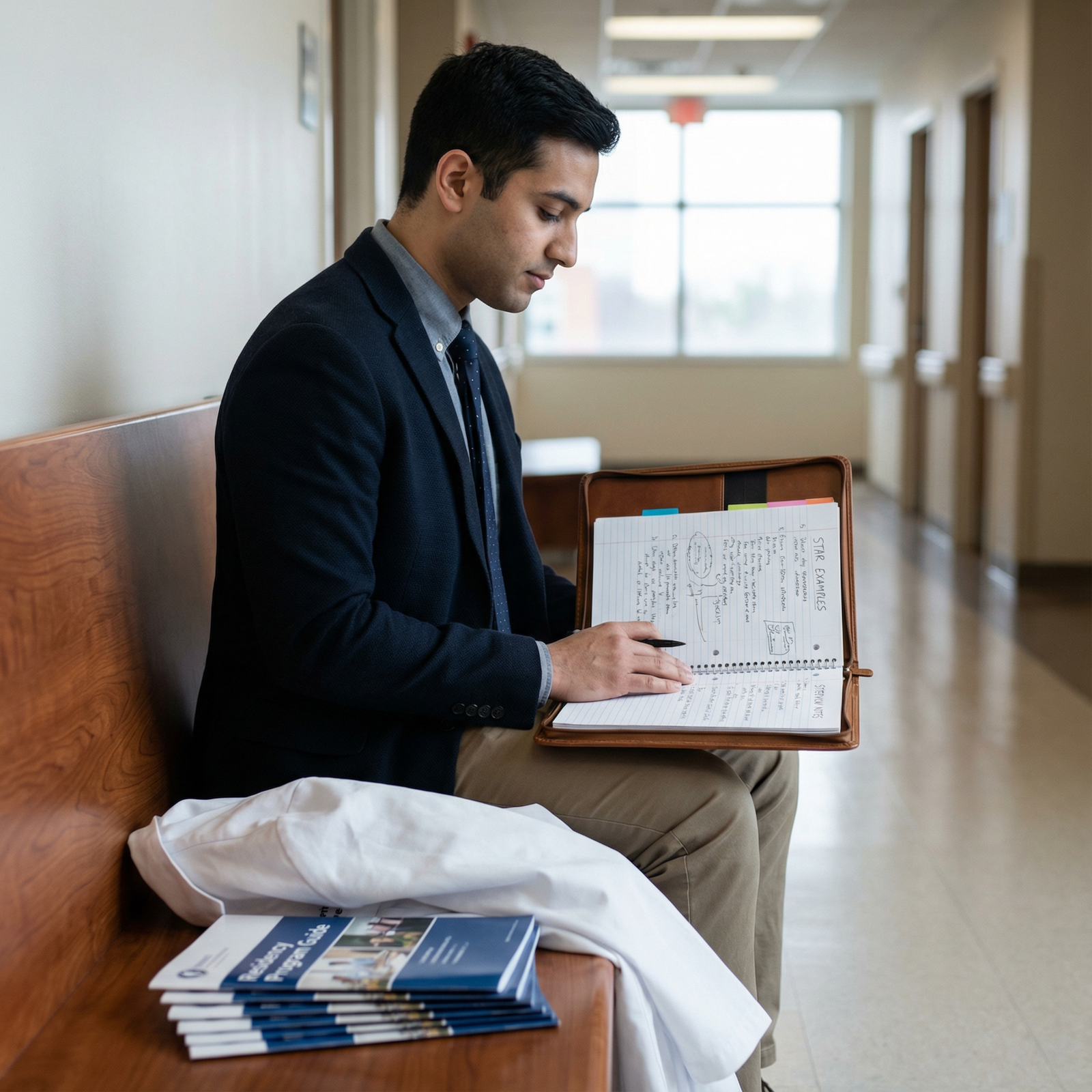

How To Actually Prepare Without Sounding Scripted

You don’t need a “perfect” story for every possible prompt. That’s how you end up sounding like everyone else.

What you need is 6–8 real, specific stories you know cold, each showing different dimensions:

- A real conflict with a peer or team member

- A genuine clinical or professional mistake / near-miss

- An example of stepping up and taking initiative (big or small)

- A time you got hard feedback and changed behavior

- A time you dealt with someone who intimidated you (attending, resident, etc.)

- A moment where you advocated for a patient or colleague

Then you flex them. The same story can be framed for conflict, leadership, communication, or resilience—if it’s real and you understand the lesson.

When you practice, stop obsessing over phrasing. Instead, focus on:

- Can you describe the scene clearly enough that someone can picture it?

- Do you say what you actually did and felt, not what “we” did in vague terms?

- Do you state what you’d do differently next time in one sentence, without fluff?

If your answer sounds like a personal statement paragraph, it’s wrong for a behavioral question.

If your answer makes you a little uncomfortable to say out loud—but still appropriate—that’s usually where the gold is.

The Bottom Line

Three things to walk away with:

- PDs are not grading your polish; they’re judging your judgment, honesty, and how you handle being wrong or uncomfortable.

- Vague, workshop-perfect answers hurt you more than a real, imperfect story with clear growth and ownership.

- Any hint of blaming nurses, staff, or peers—or dodging responsibility—sticks in PDs’ minds and will quietly push you down the list.

You do not need to be impressive in your behavioral answers.

You need to be believable. And coachable. That’s what actually gets you ranked where it matters.