Understanding the Visa Landscape as a Caribbean IMG

Navigating visas for residency as a Caribbean IMG interested in global health is complex but absolutely manageable with preparation. As a graduate of a Caribbean medical school, residency programs and immigration authorities will classify you as an international medical graduate (IMG), even if you are a U.S. citizen or permanent resident (the immigration part changes, but the “IMG” status for residency purposes remains).

From a visa perspective, Caribbean medical school residency planning revolves around three core questions:

What is my citizenship and current immigration status?

- U.S. citizen or permanent resident: You do not need a residency visa, but you are still considered an IMG for residency programs.

- Non–U.S. citizen: You must secure a visa or immigration status that allows graduate medical education in the U.S. or training in another country.

Where do I plan to train?

- United States (most common)

- Canada

- United Kingdom or other countries with global health residency track pathways

What are my long-term career goals in global health?

- Academic global health career based in the U.S. with international partnerships

- Practicing in your home country with periodic work or training abroad

- Working primarily in global health NGOs, international organizations, or humanitarian settings

Your visa choices (especially J‑1 vs H‑1B) will directly affect these career paths, your ability to stay in the U.S. after training, and your flexibility to work globally. Planning early—ideally in your third or early fourth year—allows you to align your visa strategy with your global health ambitions.

Core Visa Options for Caribbean IMGs in U.S. Residency

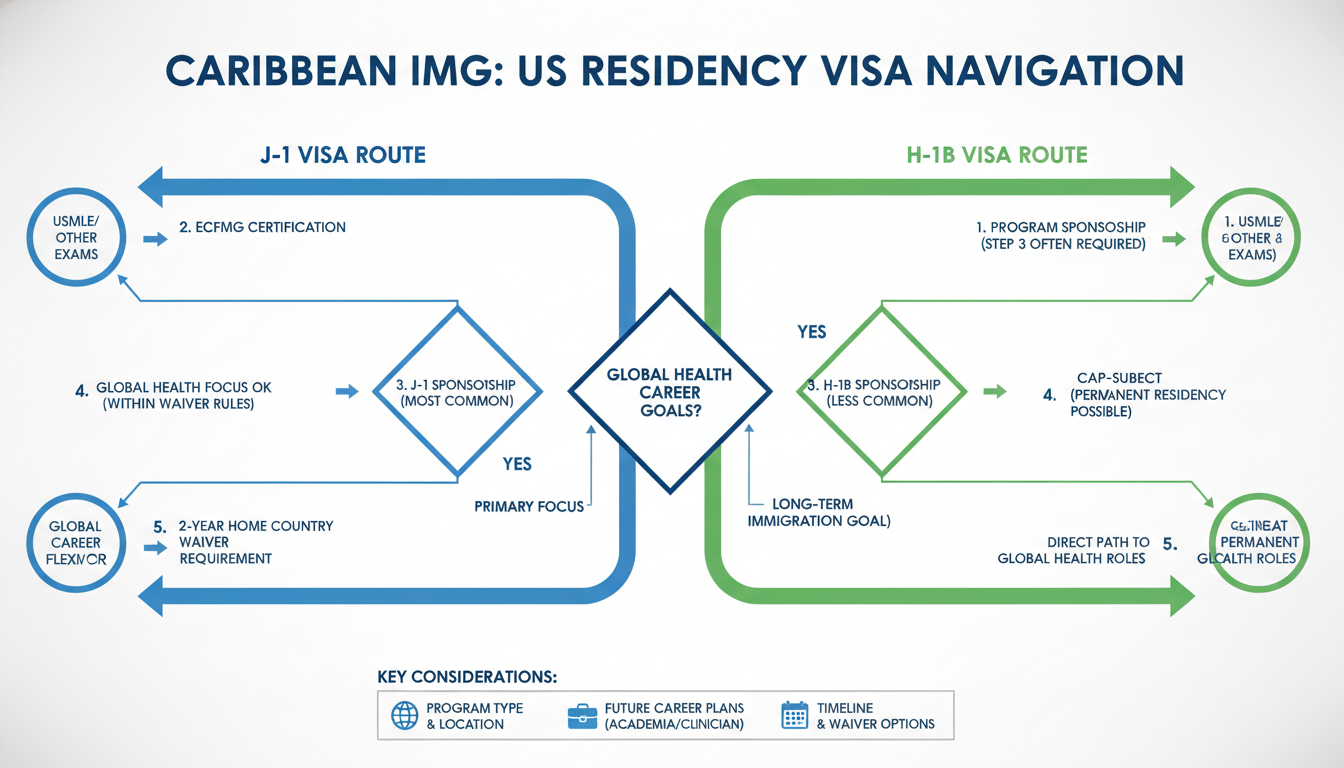

Most Caribbean medical school residency applicants who are non–U.S. citizens will train in the U.S. under one of two main visa categories: J‑1 or H‑1B. Understanding IMG visa options and the trade-offs of J‑1 vs H‑1B is essential.

The J‑1 Visa (ECFMG-Sponsored)

The J‑1 Exchange Visitor visa is the most common residency visa for IMGs in the U.S. It is sponsored by ECFMG (Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates), not by individual residency programs (though programs must accept and support J‑1 trainees).

Key features:

- Purpose: Graduate medical education (residency and fellowship)

- Sponsorship: ECFMG issues a DS-2019 form, enabling you to apply for the J-1 at a U.S. consulate.

- Duration: Length of approved training, usually capped at 7 years total (residency + fellowship)

- Full-time requirement: Must be in full-time ACGME-accredited training

Two-Year Home Residency Requirement (INA 212(e))

The most important feature of the J‑1 for Caribbean IMGs is the two-year home country physical presence requirement:

- After you complete J‑1 training, you must:

- Return to your “home country” for two years cumulatively, or

- Obtain a waiver of this requirement

- During this time (before completing 2 years or getting a waiver), you generally cannot:

- Change status to H‑1B or permanent resident in the U.S.

- Get an immigrant visa abroad to return as a permanent resident

Who is considered your “home country”?

For Caribbean IMGs, this can be nuanced:

- Usually: Your country of citizenship

- In some cases: Country of last permanent residence before J‑1 issuance

If you have dual citizenship, or if your citizenship and country of medical education differ, clarify your “home country” with ECFMG or an immigration attorney early.

Pros of the J‑1 for Caribbean IMGs:

- Widely accepted: Most community, university, and global health–oriented programs are familiar with J‑1.

- Lower administrative load for programs (ECFMG handles most compliance).

- Often faster to secure compared to H‑1B.

- Flexible for global health residency track experiences (short-term rotations abroad are common with proper approvals).

Cons of the J‑1:

- Two-year home country rule can delay U.S. long-term employment or green card.

- You must either:

- Return home for two years, or

- Obtain a J‑1 waiver job in an underserved area (commonly known as a Conrad 30 job, if your home country is not objecting), or

- Seek less common waiver routes (hardship, persecution).

For Caribbean IMGs with global health aspirations, this can be both a limitation and an opportunity—time spent working in your home country may strengthen your global health profile, but it can postpone U.S.-based academic or NGO roles.

The H‑1B Visa (Specialty Occupation)

The H‑1B visa is a work visa sponsored by an employer—in this context, your residency or fellowship program.

Key features:

- Employer-sponsored: The residency program files the H‑1B petition.

- Requirements:

- Passed USMLE Step 3 before H‑1B filing (a critical planning point)

- Valid ECFMG certification (if needed)

- Program must meet wage and Department of Labor requirements

- Duration: Up to 6 years total, including all H‑1B time (residency plus fellowships if using H‑1B again)

- Cap-exempt: Most universities and affiliated teaching hospitals are cap-exempt, meaning no lottery

Pros of H‑1B:

- No two-year home residence requirement like the J‑1.

- More straightforward path to:

- U.S. long-term employment

- Employment-based green card sponsorship (via employer)

- Attractive for IMGs who aim to stay in the U.S. in an academic or clinical role long-term.

Cons of H‑1B:

- Fewer programs willing to sponsor due to:

- Legal costs

- Administrative burden

- Requirements for Step 3 by match time

- Six-year maximum can be tight if you choose long training paths (e.g., Internal Medicine + multiple fellowships).

- Some global health–focused or community programs only sponsor J‑1, not H‑1B.

J‑1 vs H‑1B: Strategic Considerations for Global Health–Oriented Caribbean IMGs

1. Timing of Exams and Applications

If your goal is H‑1B:

- Plan to have USMLE Step 3 passed before Match (or at least before the program must file your petition).

- This usually means taking Step 3 during or immediately after your final year of Caribbean medical school.

If you are comfortable with J‑1:

- Step 3 timing is more flexible; it is not required for ECFMG-sponsored J‑1 residency.

2. Long-Term Global Health Career

Consider three common paths:

Path A: Academic Global Health Career Based in the U.S.

Example: You want to complete a global health residency track, then a global health fellowship, then work at a U.S. university directing global partnerships.- H‑1B advantages:

- Easier to transition to faculty roles and green card sponsorship.

- No J‑1 waiver or home return requirement.

- J‑1 challenges:

- Might require a J‑1 waiver job (often in underserved U.S. settings) before academic positions.

- Two-year home requirement could delay U.S.-based academic transitions.

- H‑1B advantages:

Path B: Primarily Practicing in Your Home Country with U.S. Training

Example: Train in Internal Medicine + global health track, then return to the Caribbean to build health systems and occasionally collaborate with U.S. partners.- J‑1 can be ideal because:

- Two-year home requirement aligns with your goal to return home.

- Experience can be leveraged to build a strong global health practice base.

- H‑1B is less necessary if long-term U.S. employment is not your main goal.

- J‑1 can be ideal because:

Path C: Humanitarian / NGO-Focused Global Health Career

Example: Work with WHO, PAHO, MSF, international NGOs.- Your location flexibility matters; both J‑1 and H‑1B can work, but:

- If you expect to be based in the U.S. for much of your NGO/academic work, H‑1B (and ultimately a green card) is more convenient.

- If you plan to remain internationally mobile or mostly outside the U.S., the J‑1 home requirement may be less problematic.

- Your location flexibility matters; both J‑1 and H‑1B can work, but:

3. Program Willingness and SGU / Caribbean School Patterns

If you’re from an institution like SGU (St. George’s University), Ross, AUA, or others, look at historical match data:

- Review SGU residency match statistics or your school’s equivalent:

- How many graduates match on J‑1 vs H‑1B?

- Which specialties and programs traditionally sponsor H‑1B for Caribbean IMGs?

- Some programs have a clear policy:

- “J‑1 only”

- “Will consider H‑1B for exceptional candidates”

- “H‑1B possible if Step 3 passed before rank list”

Contact program coordinators politely to clarify IMG visa options before applying broadly.

Matching from a Caribbean Medical School: Visa-Savvy Application Strategy

Residency programs evaluate Caribbean IMGs on academic, clinical, and professional criteria—but your visa status and planning can influence whether a program is able or willing to rank you.

Step 1: Clarify Your Immigration Starting Point

Before ERAS opens, be explicit about your own situation:

- Are you:

- A U.S. citizen or green card holder graduating from a Caribbean school?

- A non–U.S. citizen on a student visa in your Caribbean country or holding another status?

If you are a U.S. citizen or permanent resident, you do not need a residency visa—this simplifies your path, but you must still address “IMG” perceptions and requirements (ECFMG certification, etc.).

If you are non–U.S. citizen, identify:

- Your current passport(s)

- Any prior U.S. visa history (tourist, F‑1, etc.)

- Any issues such as prior denials or overstay that could complicate future residency visa applications

Step 2: Target Programs by Visa Type

In your ERAS research phase:

- Use program websites and FREIDA to check:

- “Sponsorship: J‑1 only”

- “J‑1 and H‑1B considered”

- “No visa sponsorship”

- For global health–focused applicants:

- University programs with global health residency track offerings often sponsor J‑1 as the default, with H‑1B reserved for specific cases.

- Some large academic centers with global health divisions may be more open to H‑1B if your profile is strong and you’ve passed Step 3.

Practical tip:

Create a spreadsheet with columns for:

- Program name

- Specialty

- Global health track (Y/N)

- Visa type supported (J‑1, H‑1B, both)

- Notes from emails/calls with coordinators

Step 3: Align Your Application Narrative with Visa Realities

In personal statements and interviews, Caribbean IMGs interested in international medicine and global health should:

- Clearly express:

- Commitment to serving underserved populations

- Desire to participate in global health electives, research, or scholarly projects

- Strategically address visa matters when asked:

- If aiming for J‑1: Emphasize your excitement to contribute both in the U.S. and back home/regionally.

- If aiming for H‑1B: Show awareness of visa requirements (e.g., Step 3 completed) and realistic long-term goals.

Avoid long, detailed legal explanations with program faculty; instead, convey that you are informed, organized, and working with appropriate advisors (school, ECFMG, or immigration counsel when needed).

Step 4: Leverage Caribbean School Networks

Caribbean medical schools with strong outcomes (e.g., SGU, Ross, AUC) often:

- Maintain match lists showing:

- Specialties, hospitals, and visa type patterns

- Have advising teams familiar with:

- Common residency visa routes for their graduates

- Which programs favor Caribbean IMGs

Ask specifically:

- “For recent SGU residency match results in Internal Medicine, how many IMGs were sponsored on J‑1 vs H‑1B?”

- “Which global health–oriented programs have consistently taken our graduates, and on what visa types?”

This kind of institution-specific intelligence is particularly valuable for Caribbean IMGs.

Post-Match and Beyond: Maintaining Status and Planning Global Health Training

After the Match: Next Steps for J‑1 and H‑1B

For J‑1:

- You’ll work with ECFMG and your matched program to:

- Submit documents for DS-2019 issuance.

- Provide proof of:

- ECFMG certification

- Contract or appointment letter

- Financial support

- You will schedule a J‑1 visa interview at a U.S. consulate.

- Once in the U.S., you must:

- Attend orientation

- Check in with your program and SEVIS (student/exchange system)

- Keep your address and status up-to-date with ECFMG

For H‑1B:

- Your residency program’s GME office will:

- File a Labor Condition Application (LCA) with the Department of Labor.

- File an H‑1B petition with USCIS on your behalf.

- You may either:

- Obtain H‑1B status via change of status within the U.S. (if eligible), or

- Consular process by attending a visa interview abroad.

- Once approved, you must:

- Work only for the sponsoring program and within the defined role.

- Maintain full-time status and refrain from unauthorized moonlighting (unless specifically allowed and authorized).

Global Health Experiences During Residency and Visa Considerations

For Caribbean IMGs passionate about international medicine, global health electives and training tracks are central to your development. Visa status affects how and where you can travel.

On J‑1:

- You may travel internationally during residency (for electives or conferences) if:

- ECFMG and your program approve the travel.

- You maintain valid J‑1 status and ensure your DS-2019 is properly endorsed for travel.

- Some programs partner with overseas sites (e.g., in the Caribbean, Africa, Latin America) for global health residency track rotations.

- Confirm that such travel is:

- Allowed under your J‑1 terms

- Properly documented as part of your training

- Confirm that such travel is:

On H‑1B:

- International travel is possible but requires:

- Valid H‑1B visa stamp in your passport (if you travel after a change-of-status approval without a stamp)

- Careful timing to avoid missing clinical duties due to administrative delays

- Many global health rotations are still feasible as part of the training program, but these must be:

- Officially sanctioned by your program and consistent with ACGME and immigration rules.

Practical example:

You are a Caribbean IMG in an Internal Medicine residency with a global health track. The program sends residents for 4-week rotations in Haiti and Guyana:

- On J‑1:

- Ensure ECFMG travel authorization.

- Maintain your U.S. address and return for scheduled duties.

- On H‑1B:

- Confirm that short overseas rotations fit within the scope of employment and training.

- Keep passport, visa stamp, and approval notice (I-797) in order for reentry.

Beyond Residency: J‑1 Waivers, Fellowships, and Long-Term Plans

Your global health and immigration strategies converge most critically at the end of residency.

If You Trained on a J‑1 Visa

You face three main options:

Return to Your Home Country for Two Years

- Align this with your global health mission:

- Work in public health, primary care, or hospital settings back home or regionally.

- Engage in research or program development that strengthens your CV for future U.S. academic or global NGO roles.

- After fulfilling the two-year requirement:

- You may apply for H‑1B or immigrant visas if you later return to the U.S.

- Align this with your global health mission:

Seek a J‑1 Waiver Job

- Waiver jobs typically:

- Are in medically underserved areas in the U.S. (urban or rural).

- Require a 3-year service commitment in full-time clinical practice.

- Common waiver pathways:

- Conrad 30 (state-sponsored), where your U.S. employer and a state health department support your waiver application.

- Federal programs (e.g., VA, HHS-designated facilities).

- For Caribbean IMGs in global health:

- This can still align with your mission—many underserved U.S. communities face global health–like challenges (limited access, migrant populations, high burden of chronic and infectious disease).

- Some positions combine domestic safety-net care with international outreach or telehealth projects.

- Waiver jobs typically:

Rare Waiver Bases (Hardship or Persecution)

- If returning home would:

- Cause exceptional hardship to a U.S. citizen/permanent-resident spouse or child, or

- Expose you to persecution (e.g., based on political opinion, religion, etc.)

- These routes are highly fact-specific and should be pursued with immigration counsel.

- If returning home would:

If You Trained on an H‑1B Visa

Your next steps are more flexible:

- You can:

- Move directly into another H‑1B role (e.g., faculty or attending).

- Begin a green card process via employer sponsorship while maintaining H‑1B.

- If you pursue fellowship:

- Some fellowships will:

- Continue H‑1B sponsorship (especially at academic centers).

- Or, prefer J‑1 (be careful not to introduce a new 2-year requirement by switching to J‑1 after H‑1B if your goal is to remain in the U.S.).

- Some fellowships will:

For global health–focused careers, H‑1B plus eventual permanent residency often allows:

- Greater flexibility to:

- Travel for extended global health work

- Hold long-term U.S.-based academic or NGO positions

- Lead global research consortia

Practical Advice for Caribbean IMGs: Putting It All Together

Start Early (End of Second / Early Third Year)

- Learn the basics of residency visa categories.

- Decide if J‑1 is acceptable or if you will push for H‑1B.

- Schedule Step 3 accordingly if aiming for H‑1B.

Use Your School’s Data and Advisors

- Examine Caribbean medical school residency outcomes, including:

- Visa patterns

- Global health–friendly programs

- Seek mentors among graduates now working in:

- Global health residency track roles

- J‑1 waiver positions

- Academic global health

- Examine Caribbean medical school residency outcomes, including:

Be Honest and Organized in Applications

- Don’t misrepresent your current status or visa needs.

- Have a concise explanation of:

- Your immigration status

- Your preferred visa (if applicable)

- Clarify with each program what they are willing to sponsor before ranking them highly.

Think Beyond Residency from Day One

- Every visa choice shapes:

- Where you can live

- How easily you can work in underserved areas or abroad

- Your timeline for long-term residence in the U.S. (if desired)

- Align your strategy with your global health vision:

- If your heart is set on returning to the Caribbean to strengthen health systems, J‑1 with home-country return may be ideal.

- If you envision a U.S.-based academic global health career, H‑1B may better support that path.

- Every visa choice shapes:

Consult Professionals When Needed

- Immigration rules change; this article provides general guidance, not legal advice.

- For complex cases (dual citizenship, previous visa issues, humanitarian concerns), consider:

- Speaking to an immigration attorney

- Using ECFMG or institutional international office guidance

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. I’m a citizen of a Caribbean country but studied at a Caribbean medical school that places many graduates in the U.S. Do I automatically qualify for a U.S. residency visa?

No. Matching to a residency does not automatically grant a visa. You must still qualify for and obtain an appropriate residency visa (usually J‑1 or H‑1B) based on your credentials, program sponsorship, and consular approval. Your school’s strong match record (such as an SGU residency match track record) helps demonstrate academic quality but does not replace immigration steps.

2. If I plan to return to my Caribbean home country to practice global health, should I avoid the J‑1 because of the two-year rule?

Not necessarily. If your plan already includes returning home, the J‑1’s two-year home requirement may fit naturally with your goals. During those two years you can build a robust portfolio in international medicine, contribute to health systems in your region, and later decide whether to pursue further U.S. training or global roles.

3. Can I switch from J‑1 to H‑1B during or after residency to stay in the U.S.?

In most cases, if you are subject to the J‑1 two-year home country requirement, you cannot change to H‑1B status or obtain a green card until you either:

- Complete two years of physical presence in your home country, or

- Obtain a waiver of that requirement.

Switching mid-training is unusual and complex; always consult immigration counsel and ECFMG if considering it.

4. Do global health residency tracks sponsor visas differently than regular programs?

Typically, global health residency track positions are structurally the same as standard categorical residency slots with additional global health curriculum and rotations. Visa sponsorship policies (J‑1 vs H‑1B) are determined by the institution, not by the track. Some global health–oriented academic centers are open to H‑1B sponsorship for strong candidates, but many default to J‑1 for IMGs. Always verify directly with the program.

By understanding the visa landscape, planning early, and aligning your choices with your global health ambitions, you can move from Caribbean medical school residency aspirations to a sustainable, meaningful career in international medicine.