Understanding the Big Picture: Visas and General Surgery Residency

For international medical graduates (IMGs), matching into a general surgery residency in the United States is challenging enough. Adding visa navigation on top of exam scores, letters, and interviews can feel overwhelming. Yet for many programs—especially in surgery—your visa status is a key part of how they evaluate your application and whether they can rank you.

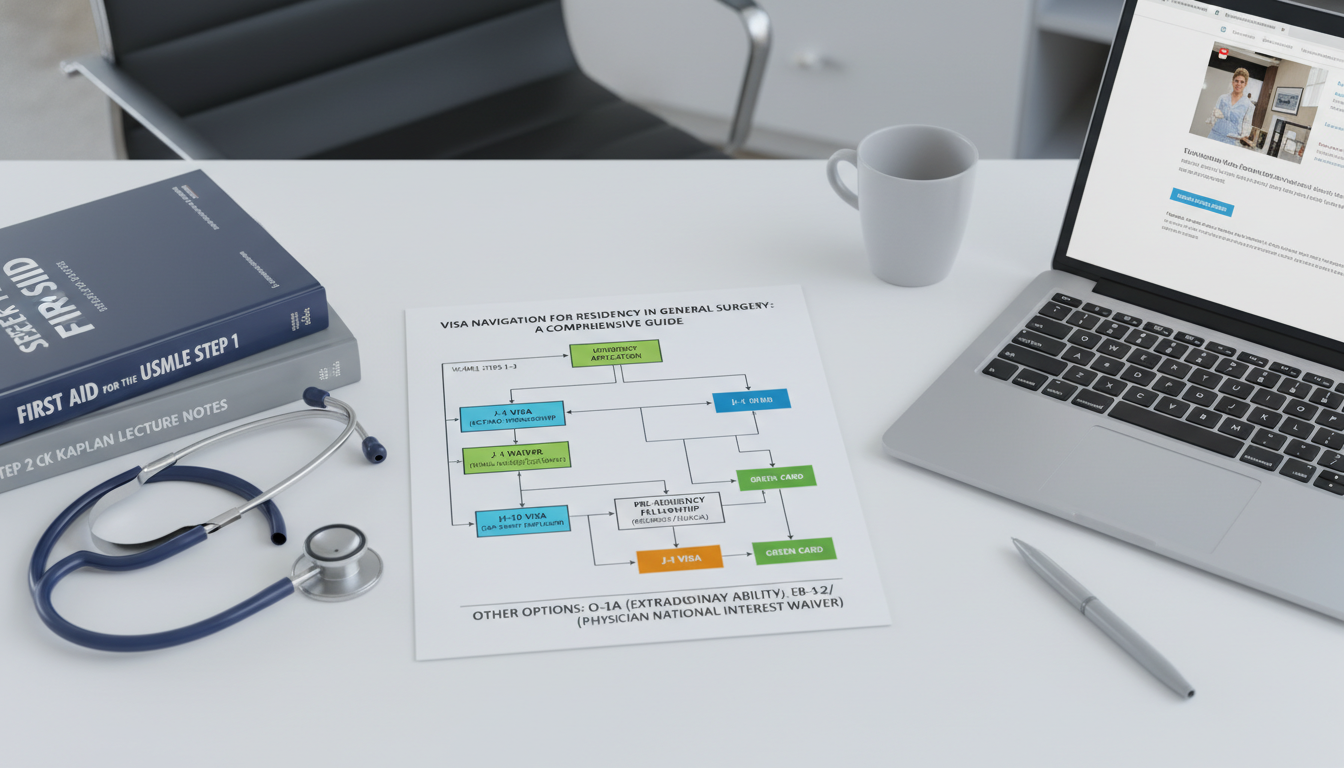

This guide focuses on helping you, as an IMG interested in general surgery, understand:

- How visa status affects your surgery residency match

- The main visa pathways: J‑1 vs H‑1B

- Typical expectations of general surgery programs

- Steps to take in medical school or gap years to be visa-ready

- How visa issues intersect with fellowship, career, and green card planning

While rules can change and institutional policies differ, this overview will give you a solid, strategic framework so you can make informed decisions early and avoid preventable surprises later.

Common Visa Pathways for IMGs in General Surgery

1. J‑1 Visa (ECFMG-Sponsored Exchange Visitor)

For most IMGs entering a US GME program, the J‑1 physician visa is the standard route. It is sponsored by the ECFMG (Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates), not by individual hospitals.

Key features

- Sponsor: ECFMG

- Purpose: Graduate medical education (residency/fellowship)

- Typical duration: Length of accredited training, up to 7 years in total (sometimes more with special approvals)

- Full-time requirement: Must be in full-time, ACGME-accredited training

- Work location: Only at approved training sites; outside work (moonlighting) is heavily restricted or not allowed

- Two-year home-country requirement (INA 212(e)): After finishing training, you usually must:

- Return to your home country for a total of 2 years, or

- Obtain a J‑1 waiver before moving on to another US status (like H‑1B) or green card

Why general surgery programs often prefer J‑1

Many general surgery programs—especially community programs and some academic centers—find the J‑1 easier to work with because:

- The administrative burden is largely handled by ECFMG, not the program’s legal office.

- Institutional policies may limit or restrict H‑1B sponsorship due to cost and complexity.

- J‑1 is clearly defined and familiar to GME offices nationwide.

Practical implications for you

- You must stay continuously enrolled and in good standing in your residency.

- If you need extended time (e.g., research years, remediation, medical leave), you need coordination with ECFMG and your program to maintain status.

- You must plan for the two-year home residency or for a waiver pathway well before the end of your residency (especially if you are aiming for competitive fellowships like surgical oncology, vascular, or cardiothoracic surgery).

2. H‑1B Visa (Specialty Occupation Worker)

The H‑1B visa is another route for residency training, but in general surgery it is less common than J‑1, and often more difficult to secure.

Key features

- Sponsor: The hiring hospital/institution (not ECFMG)

- Purpose: Temporary specialty occupation employment

- Typical duration: Up to 6 years (initial period + extensions), though time spent outside the US may “recapture” additional time

- Requires:

- Passing USMLE Step 3 before H‑1B petition filing

- A valid, unrestricted medical license or eligibility for temporary/in-training license (varies by state)

- Usually no two-year home residency requirement

- More flexibility for later green card processes and job transitions

Why H‑1B can be attractive to surgery applicants

- No J‑1 home-country residency requirement.

- Easier to transition directly to:

- Another H‑1B position (e.g., attending job)

- Employment-based green card categories (e.g., EB‑2)

- Some institutions allow limited moonlighting under H‑1B (when permitted by state law, GME policy, and contract).

Challenges and limitations

- Fewer programs offer H‑1B sponsorship for general surgery residency compared with J‑1.

- The hospital pays legal fees and petition costs, and must file a Labor Condition Application (LCA)—some institutions simply do not allow this for residents.

- You must pass Step 3 before Match deadlines and before the visa petition is filed—this is a major logistical barrier for many IMGs.

- H‑1B is tied to a specific employer and work location; significant schedule or site changes may require amendments.

In general surgery specifically

Academic general surgery programs with large legal and GME infrastructures are more likely to offer H‑1B, but even there, policies may be:

- “J‑1 only”

- “J‑1 preferred; H‑1B considered in exceptional cases”

- “H‑1B allowed only if Step 3 is passed and there is adequate lead time before July 1”

When researching programs, always check their residency visa policies on their websites or confirm directly with the program coordinator.

3. Other Scenarios: Green Card, EAD, and Non-Standard Statuses

Some IMGs arrive at application time with a status that does not require a residency visa:

- US permanent resident (green card holder)

- US citizen (naturalized or by birth abroad)

- Dependent visas with work authorization (e.g., certain EADs like J‑2 with EAD, H‑4 with EAD, pending asylum EAD, TPS EAD, etc.)

Advantages for surgery residency

- Programs usually consider you in the same pool as US graduates in terms of visa complexity.

- No J‑1 two-year rule and no H‑1B restrictions (if you have independent work authorization via EAD/green card).

- Fewer institutional barriers—and at times more willingness—from programs that otherwise “do not sponsor visas.”

Cautions

- Some EAD categories are time-limited or depend on another person’s status.

- For a long training pathway (5 years general surgery + optional research + 1–3 years of fellowship), you must ensure your work authorization will last or be renewable.

- Always consult an immigration attorney for long-term planning, especially if your path depends on unstable or discretionary statuses.

J‑1 vs H‑1B: How to Choose Strategically

For most IMG applicants considering general surgery, the core question is: J‑1 vs H‑1B. Both can work; the “better” choice depends on your timeline, goals, and program availability.

1. Comparing J‑1 and H‑1B for General Surgery

Training phase (residency years)

J‑1

- Widely accepted in general surgery programs.

- ECFMG handles much of the paperwork.

- Less flexibility for moonlighting or side clinical work.

- Clear rules but strict compliance requirements.

H‑1B

- Fewer programs offer it for surgery residency.

- Requires Step 3 in advance—hard for many IMGs to arrange.

- Potential for somewhat greater flexibility within the institution.

- More institutional paperwork and legal oversight.

Post-residency and fellowship

From J‑1:

- You either:

- Return to your home country for 2 years, or

- Obtain a J‑1 waiver (e.g., Conrad 30, VA waiver, academic waiver).

- Many surgical fellowships do accept J‑1 (through ECFMG) but can be more selective if you haven’t addressed your long-term plans.

- If you get a waiver job (usually in underserved areas), you typically work 3 years in that position, then can pursue further career steps and usually move to H‑1B or green card.

- You either:

From H‑1B:

- No two-year home residency requirement.

- You can:

- Move to another H‑1B job (e.g., attending or fellowship)

- Start employment-based green card process directly.

- Some fellowships may also sponsor H‑1B; others sponsor J‑1, so transitions need planning.

Green card implications

- J‑1:

- While on J‑1 subject to 212(e), you typically cannot adjust status in the US to permanent residence until you either:

- Complete the 2-year home residency, or

- Obtain a J‑1 waiver.

- While on J‑1 subject to 212(e), you typically cannot adjust status in the US to permanent residence until you either:

- H‑1B:

- Considered “dual intent”—you can be on H‑1B while pursuing a green card.

- Often the smoother path if you have a clear plan for long-term US practice.

2. Practical Questions to Ask Yourself

When deciding between J‑1 and H‑1B, consider:

Do I realistically have time to pass USMLE Step 3 before applications or Rank List deadlines?

- If no, J‑1 will likely be your main feasible route.

Are my target general surgery programs willing to sponsor H‑1B?

- Check program websites carefully.

- Email coordinators politely if it’s unclear.

- Filter programs by visa policy when building your apply list.

How certain am I that I want to stay long-term in the US after training?

- If highly committed to US practice, H‑1B may give more flexibility.

- If open to returning home, J‑1 plus the 2-year requirement may be acceptable.

How competitive is my profile for general surgery?

- General surgery is highly competitive for IMGs.

- Some strong applicants may target primarily H‑1B-friendly academic centers; others may broaden to J‑1-accepting programs to increase chances.

3. Strategy Example: Two Different Applicants

Applicant A: Strong profile, early Step 3

- Passed Step 3 by mid‑Med 4 or during a research year.

- Strong US clinical experience and research in surgery.

- Competitive for academic general surgery programs.

- Strategy:

- Prioritize programs that offer H‑1B.

- Still list some J‑1 programs as backup.

- Discuss long-term goals (e.g., academic surgical oncology career) and mention how H‑1B fits that plan in interviews when appropriate.

Applicant B: Solid profile, but Step 3 not done

- Great USMLE Step 1/2 CK, but no Step 3 yet.

- Has several general surgery observerships.

- Strategy:

- Apply broadly to J‑1-accepting programs, including community and university-affiliated sites.

- Consider taking Step 3 later during internship or PGY‑2 to open H‑1B options for fellowship or employment.

- Focus on match success first; then plan J‑1 waiver or post-residency strategy.

Program Policies, Application Strategy, and Communication

1. How General Surgery Programs View Visa Issues

General surgery residencies vary widely, but common patterns include:

Visa-agnostic but policy-bound programs

They are happy to train IMGs, but the hospital or university has strict rules:- Some are “J‑1 only”

- Some accept both J‑1 and H‑1B with conditions

- A few accept no visa sponsorship at all (you must have green card/US citizenship/EAD)

Selectively IMG-friendly programs

Some community or smaller academic programs:- Welcome IMGs with good scores and strong clinical skills

- Routinely sponsor J‑1

- Have limited willingness or resources for H‑1B

Highly competitive academic programs

For these, especially those heavily research-oriented:- Visa type may be less important than your academic portfolio

- But if they have an institutional bias towards J‑1, you may have no choice even with Step 3.

2. Reading Websites and Asking the Right Questions

During program research:

- Check the “Eligibility & Visa” section of each general surgery residency website.

- Look for specific language:

- “We accept ECFMG-sponsored J‑1 visas only.”

- “We sponsor J‑1 and H‑1B visas for eligible candidates.”

- “We do not sponsor visas.”

- If unclear, email the coordinator with a very short, precise question, e.g.:

Dear [Name],

I am an international medical graduate applying for your General Surgery Residency program. Could you please confirm which visas your institution sponsors for categorical residents (J‑1, H‑1B, or others)?Thank you for your time,

[Your Name]

Avoid long emails about your full background at this stage. Programs appreciate concise, direct questions.

3. Aligning Your ERAS Application with Visa Realities

A few practical tips:

ERAS visa question: Answer accurately. If you need sponsorship, indicate that.

Personal statement:

- You may briefly mention your long-term plan within the US system (e.g., academic career, interest in underserved surgery).

- Avoid detailed legal discussions about J‑1 waivers, etc. That level of detail is usually better for one-on-one conversations or later in training.

Interviews:

If asked about visa needs:- Be confident, clear, and concise.

- Demonstrate you understand the basics and are committed to complying with requirements.

Example response:

“I will require visa sponsorship to train in the US. I’m eligible for an ECFMG-sponsored J‑1 and I’ve studied the post-residency options, including waiver programs for underserved areas. I’m happy to follow whichever option aligns best with your institution’s policies.”

Planning for the Entire Path: From Match to Attending Surgeon

Visa decisions affect not only your ability to enter a general surgery residency, but also your entire training and career arc: residency → fellowship → early attending years.

1. Residency Years (PGY‑1 to PGY‑5)

Focus areas:

- Maintain status:

- Keep all documents (passport, DS‑2019 or I‑797, I‑94) valid.

- Notify the GME office of address changes or extended leaves.

- Performance and evaluations:

Visa issues become irrelevant if performance is poor. General surgery is demanding; prioritize:- Clinical excellence

- Technical skill development

- Professionalism and teamwork

- Early career discussions:

By PGY‑3, start talking informally with mentors about:- Fellowship goals

- Geographic preferences

- Academic vs community practice

2. Fellowship (Surgical Subspecialties)

Many general surgery graduates pursue fellowships (e.g., colorectal, MIS, vascular, surgical oncology, cardiothoracic, trauma/critical care).

As a J‑1 holder:

- You can usually extend J‑1 visa through ECFMG for fellowship (within the maximum duration limits).

- Competitive fellowships may ask about long-term goals; some may subtly favor applicants with clearer post-fellowship plans (such as J‑1 waiver positions).

As an H‑1B holder:

- Fellowship programs must be willing to either:

- Sponsor H‑1B for you, or

- Accept you on a new J‑1 (possible in some cases if you had not been subject to 212(e) before; details require legal review).

- Visa transitions at this stage can be complex—start planning at least 12–18 months before fellowship start.

3. J‑1 Waivers and First Attending Job

If you trained on a J‑1 and want to stay in the US, you’ll likely need a J‑1 waiver.

Common options:

Conrad 30 waivers

- State-based programs that offer waiver slots for physicians who commit to work in designated underserved areas for usually 3 years.

- Availability and competitiveness vary by state and by specialty (general surgery vs primary care).

- Some states are more open to surgical specialties; others are heavily primary-care focused.

Federal waivers

- Through agencies like the VA (Veterans Affairs), HHS, or DoD.

- Often tied to academic or research positions, or service to specific populations.

Hardship or persecution waivers

- Based on specific personal circumstances (e.g., exceptional hardship to a US citizen spouse/child, or fear of persecution on return).

- Legally complex and generally require a specialized attorney.

For general surgeons, Conrad 30 or VA waivers are often the primary path. The jobs:

- Are typically in smaller cities or rural settings

- Can be clinically intense but rewarding

- Often allow you to start an H‑1B-based career and later pursue a green card

4. Long-Term Immigration Goals

If you plan to establish a long-term surgical career in the US, think ahead:

On H‑1B:

- Explore employer-sponsored green card options (EB‑2, possibly with National Interest Waiver if your profile merits it).

- Academic surgeons with strong research may pursue EB‑1 categories.

On J‑1 (post-waiver job):

- After completing waiver service (usually 3 years), you can typically move freely in H‑1B or permanent positions and start the green card process.

Early in your career, a brief discussion with an immigration attorney who understands physicians can save you years of trouble and missed opportunities.

Practical Steps: Timeline and Action Plan for IMG Surgery Applicants

Medical School / Early Years

- Confirm your IMG visa options early (J‑1 vs H‑1B vs other).

- Plan US clinical experiences and letters of recommendation.

- If targeting H‑1B:

- Aim to complete USMLE Step 3 as early as realistically possible.

- If leaning J‑1:

- Read ECFMG’s latest guidelines for J‑1 physicians.

Application Year (ERAS / NRMP)

- Build a program list that reflects:

- Your competitiveness

- Visa policies of each program

- Clearly indicate your need for sponsorship in ERAS.

- Keep documents (passport, exam scores, ECFMG certificate) ready—programs sometimes need quick verification.

Post-Match / Pre-Start

- Work closely with:

- GME office

- Program coordinator

- ECFMG (if J‑1) or the institution’s legal office (if H‑1B)

- Submit all required documents on time:

- DS‑2019 application (for J‑1)

- H‑1B petition paperwork (for H‑1B)

- Schedule your visa interview early at the US consulate, accounting for potential delays or administrative processing.

During Residency

- Maintain status meticulously.

- Keep copies of all your immigration documents.

- Build a strong portfolio (operative logs, evaluations, research) to broaden fellowship and job options.

- By PGY‑3–4:

- Discuss fellowship interests and possible visa needs with mentors.

- If on J‑1, start learning about waiver programs and states that are open to general surgeons.

FAQ: Visa Navigation for General Surgery Residency

1. Do most general surgery residency programs sponsor J‑1 or H‑1B visas?

Most programs that sponsor visas for IMGs will sponsor J‑1 via ECFMG. A smaller subset also sponsor H‑1B, and some do not sponsor any visa at all, accepting only US citizens/permanent residents. For a competitive specialty like general surgery, expect that many of your realistic options will be J‑1 unless you have Step 3 early and target H‑1B-friendly institutions.

2. Is it worth taking USMLE Step 3 before applying if I want an H‑1B?

If your goal is H‑1B sponsorship for residency, passing Step 3 before the application cycle or by Match Rank List deadlines can significantly expand your options—particularly at academic centers that support H‑1B. However, don’t rush Step 3 if it risks a poor score or failure. If your timeline is tight, it can be reasonable to match on a J‑1 first and consider H‑1B later for fellowship or attending roles.

3. Can I switch from J‑1 to H‑1B during or after general surgery residency?

Usually, you cannot simply “switch” from J‑1 to H‑1B if you are subject to the two-year home residency requirement (212(e)). You must either:

- Complete two years in your home country, or

- Obtain a J‑1 waiver (e.g., via Conrad 30, VA, or hardship/persecution) and then move into an H‑1B position.

Some narrow exceptions exist depending on previous statuses or specific circumstances, but most IMGs in general surgery who start on J‑1 will need to address 212(e) before moving to long-term H‑1B or green card status.

4. I already have a green card. Do I still need to worry about visa policies when applying to general surgery?

If you are a US permanent resident (green card holder), you generally do not need visa sponsorship and can be treated administratively like a US graduate in terms of immigration status. Programs that “do not sponsor visas” can still rank you. However, as an IMG you’ll still be evaluated on scores, clinical experience, and letters—and general surgery remains highly competitive—so you should still apply strategically and broadly.

This guide should serve as a roadmap for understanding and planning your visa navigation for residency in general surgery. Individual cases can be complex, so always verify current regulations with official sources and, when needed, seek personalized advice from an immigration attorney familiar with physicians and GME.