Understanding the Visa Landscape for IMGs in Medical Genetics

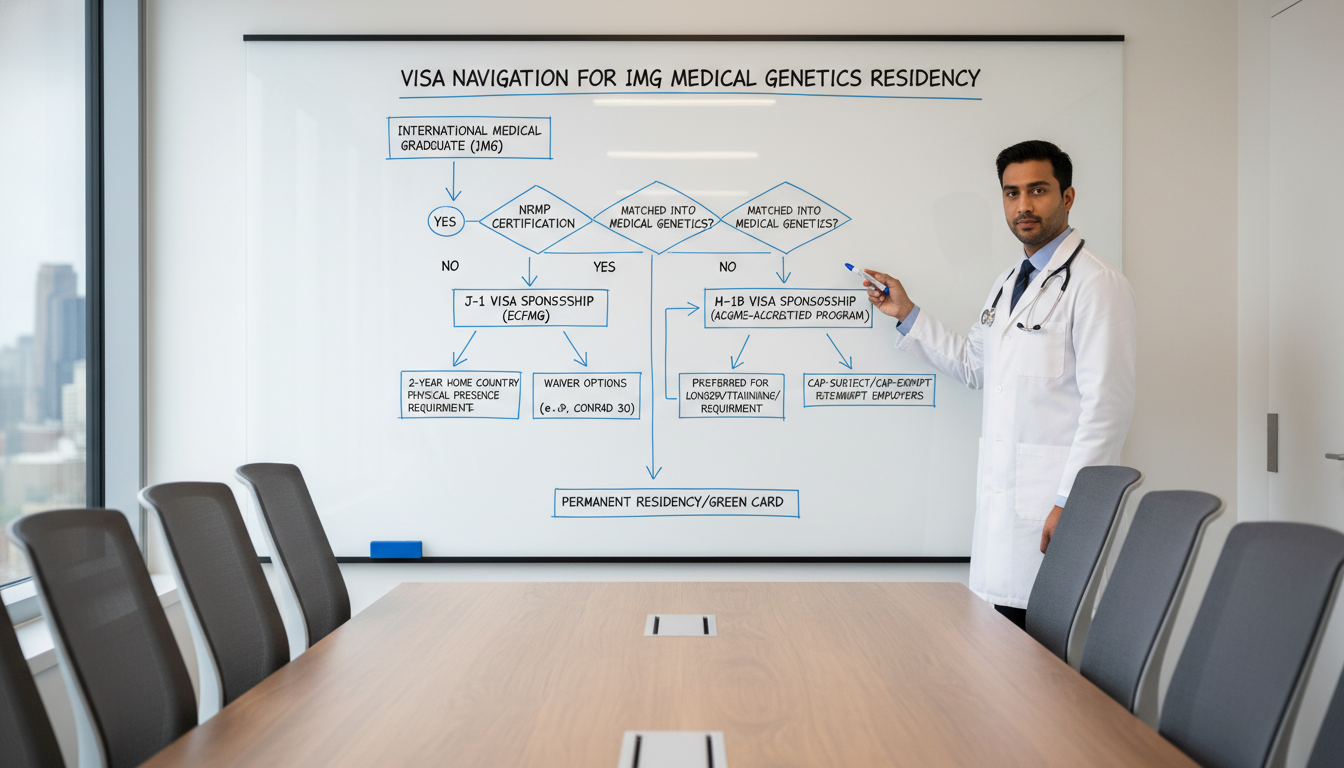

For an international medical graduate (IMG) aiming for a medical genetics residency in the United States, navigating visa options can be as complex as understanding a chromosomal microarray. Visa strategy is not just a bureaucratic formality—it directly impacts where you can match, what programs can rank you, your ability to moonlight, and your long‑term career and immigration plans.

This IMG residency guide focuses specifically on visa navigation for those targeting medical genetics residency programs. While core principles apply across specialties, medical genetics has unique patterns in program sponsorship, training length, and career trajectories that should shape your visa decisions.

In this article, you’ll learn:

- The main visa types used in U.S. residency (J‑1 vs H‑1B) and how they apply to medical genetics

- How visa preferences differ across medical genetics programs

- Strategic planning for the genetics match with your visa in mind

- Common pitfalls and practical steps to optimize your application and long‑term options

Throughout, remember: programs care about your visa status because it affects their ability to bring you on board smoothly and legally. A clear, realistic plan makes you a more attractive candidate.

Core Visa Options for Medical Genetics Residency

1. The J‑1 Physician Visa: Most Common Pathway

For IMGs entering U.S. GME, the J‑1 exchange visitor physician visa, sponsored by the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG), remains the most common route. For many future medical geneticists, it is the only realistic option.

Key features of the J‑1 physician visa

- Primary sponsor: ECFMG (not your residency program directly)

- Purpose: Graduate medical education and training (residency, fellowship)

- Duration: Typically issued year‑by‑year, up to a cumulative 7‑year limit (extensions beyond that are rare and require special justification)

- Home-residency requirement:

- Most J‑1 physicians are subject to the two‑year home country physical presence requirement (INA 212(e))

- You must return to your home country OR obtain a waiver before you can:

- Apply for most work visas (e.g., H‑1B)

- Adjust status to permanent residency (green card)

Pros of J‑1 for medical genetics IMGs

- Widely accepted: Many medical genetics & genomics programs that sponsor IMGs support J‑1 but not H‑1B.

- Predictable sponsorship: ECFMG has an established, standardized process.

- Flexible for training length: Most genetics pathways (2–4 years) fit well under the 7‑year cap, especially if your prior training in the U.S. was limited.

Cons of J‑1

- Two‑year home requirement: Major consideration if you plan to stay in the U.S. long‑term.

- Waiver jobs: If you seek to remain in the U.S. after training, you may need a J‑1 waiver job (often in an underserved or specific institutional setting).

- Less flexible for research‑only or non‑clinical roles immediately after training without navigating waiver or home return issues.

Practical implications for medical genetics

- Many medical genetics careers are based in academic medical centers. Some of these institutions have J‑1 waiver opportunities tied to clinical genetics roles, but these positions can be limited and competitive.

- If you expect to do a combined residency (e.g., pediatrics + medical genetics over 4–5 years), ensure your full training plan fits within the 7‑year J‑1 limit including any prior U.S. training.

2. The H‑1B Visa: Attractive but Less Available

The H‑1B temporary worker visa (specialty occupation) is the other main clinical training option. It can be very advantageous but is not universally available in medical genetics residency.

Key features of H‑1B for residency

- Employer-sponsored: The residency program (not ECFMG) files the petition.

- Requirements:

- USMLE Step 3 usually required before they can file the petition.

- You must meet state medical licensure eligibility requirements (varies by state).

- Duration: Up to 6 years (typically issued in 3‑year increments), with possible extensions in certain green card processes.

- No two‑year home requirement: You are not subject to the J‑1 home residency rule.

Pros of H‑1B for a future medical geneticist

- More direct path to long‑term U.S. practice and potential green card.

- Some institutions prefer H‑1B for continuity—easier to transition from residency to attending roles or research/academic work.

- Avoids complexities of J‑1 waiver jobs.

Cons of H‑1B

- Fewer genetics programs offer H‑1B: This is crucial. Many medical genetics residency programs explicitly take only J‑1 candidates.

- Step 3 timing:

- You must pass Step 3 early, often before rank lists are due or before the program can finalize your contract.

- This can be hard if your medical genetics residency starts right after a non‑U.S. internship.

- More administrative burden and cost for the program; some smaller genetics departments cannot support this.

Practical advice

- If you strongly prefer H‑1B, your program list must be filtered to include only genetics programs that explicitly sponsor H‑1B.

- Be realistic: many IMGs entering medical genetics use J‑1, then manage their long‑term immigration via J‑1 waiver positions or later visa transitions.

3. Other Less Common Visa Pathways

These are less typical but occasionally relevant:

O‑1 Visa (Individuals with Extraordinary Ability)

- Used by some physician-scientists, especially those in research-heavy genetics or genomics.

- Hard to obtain early in your career; more feasible after substantial publications, grants, or major recognitions.

- Not commonly used for core ACGME residency, but can be relevant for post-residency research roles.

Green Card Holders / Other Immigrant Statuses

- If you already hold a green card or other immigrant status, visa navigation is much simpler.

- In that case, your residency process is similar to that of U.S. graduates; many programs favor candidates without complex visa needs.

How Medical Genetics Training Structure Affects Visa Strategy

Medical genetics has unique training pathways, and understanding them is essential when planning your residency visa and overall timing.

1. Common Medical Genetics Residency Pathways

In the U.S., the main ABMGG/ACGME pathways are:

Categorical Medical Genetics and Genomics (MGG)

- Often a 2‑year residency following completion of a primary residency (e.g., pediatrics, internal medicine, OB/GYN).

- Some institutions run combined programs (e.g., Pediatrics/Medical Genetics over 4–5 years).

Combined Programs

- Examples: Internal Medicine/Medical Genetics, Pediatrics/Medical Genetics, Maternal‑Fetal Medicine/Genetics, etc.

- These can span 4 to 6 years of integrated training.

Post‑Residency Entry

- Many IMGs first complete a primary residency (often in pediatrics or internal medicine), then match into a medical genetics residency or fellowship.

2. Visa Implications of Different Pathways

Scenario A: You’re matching first into a primary residency (e.g., Pediatrics), then Medical Genetics

- Most IMGs will first focus on visa options for the initial residency.

- If that first residency is on a J‑1, your total GME time (pediatrics + genetics) must fit within the 7‑year J‑1 maximum.

- Example timeline:

- Pediatrics residency: 3 years

- Medical genetics & genomics residency: 2 years

- Total: 5 years (well within J‑1 limits as long as you haven’t done significant prior U.S. training).

Practical tip:

If you already completed a residency or fellowship in another country but not in the U.S., it doesn’t count toward the J‑1 limit. Only J‑1 time physically spent in the U.S. as a trainee is counted.

Scenario B: Direct or Combined Medical Genetics Programs for IMGs

Some institutions offer combined tracks (e.g., Pediatrics/Medical Genetics) where you match straight into an integrated program via ERAS/NRMP.

Visa considerations:

- You must ensure the full integrated program duration can be covered by either:

- A single J‑1 period (within 7 years), or

- Planned H‑1B periods (within 6 years, with careful timing if subspecialty training is added).

- Programs are sometimes more conservative about offering H‑1B for long, integrated tracks due to cost and paperwork over many years.

Scenario C: Already in U.S. Training, Transitioning into Genetics

If you are currently in an internal medicine, pediatrics, or OB/GYN residency:

On a J‑1:

- You can usually continue with J‑1 if you move into an ACGME‑accredited medical genetics residency and stay within the 7‑year cap.

- You’ll need continued ECFMG sponsorship, supported by your new genetics program.

On an H‑1B:

- Your new employer (genetics program/hospital) must file a new H‑1B petition (change of employer) or amend the existing one.

- Coordination and timing are critical to avoid status gaps.

J‑1 vs H‑1B for Medical Genetics: Strategic Comparison

The “J‑1 vs H‑1B” decision is one of the most important parts of any IMG visa options discussion. For a career in medical genetics, the trade‑offs have some specific nuances.

1. Short‑Term: Matching into a Genetics Program

When applying to the genetics match, programs ask:

- Do you need visa sponsorship?

- If yes, do you need J‑1 or H‑1B?

- Are you already in the U.S. on a specific status?

From the program’s perspective:

- J‑1 is administratively simpler: they rely on ECFMG.

- H‑1B requires institutional willingness to handle legal fees and administrative tasks, and the candidate must have passed USMLE Step 3.

Actionable advice:

- When researching programs:

- Check their ERAS/NRMP program description for visa policies.

- Visit the department or GME office website and verify up‑to‑date information.

- Email the program coordinator or program director if unclear—ask direct questions like:

- “Do you sponsor J‑1 visas?”

- “Do you sponsor H‑1B visas for medical genetics residents?”

- Maintain a spreadsheet tagging each program as:

- J‑1 only

- J‑1 and H‑1B

- No visa sponsorship

2. Medium‑Term: Training Length and Career Plans

Think about your 5‑ to 10‑year plan:

- Do you plan to do additional subspecialty training after medical genetics (e.g., biochemical genetics)?

- Do you want to combine clinical work with laboratory genetics, molecular genetics, or genomic research?

- Are you committed to a career in the U.S., or open to returning to your home country (which may value U.S. genetics expertise highly)?

J‑1 path planning

- Suitable if:

- You’re comfortable with the possibility of a J‑1 waiver job (often clinical, sometimes remote from major academic centers), or

- You are genuinely interested in returning home to help build genetics services.

- You may later transition from J‑1 waiver employment to H‑1B or a green card through employer sponsorship.

H‑1B path planning

- Attractive if you want a straightforward path to long‑term employment in the U.S. after residency.

- If your ultimate goal is genomics research or lab‑based genetics in an academic center, some institutions may sponsor you for a green card directly from H‑1B.

3. Long‑Term: Immigration and Career Stability

Consider:

- Home requirement (J‑1): If you have strong reasons not to return home (safety, career, family), this can be a major constraint.

- Green card timing:

- On H‑1B, your employer may start a PERM / I‑140 process during or after residency/fellowship.

- On J‑1, you generally need either to:

- Complete the two‑year home stay and then seek immigrant options, or

- Get a J‑1 waiver and then move to a work visa or green card route.

Bottom line for medical genetics IMGs

- If your primary aim is simply to match into and complete medical genetics residency, J‑1 will usually be the most accessible and realistic option.

- If you are strongly committed to a U.S.‑based long‑term genetics career and have the portfolio to meet H‑1B and Step 3 requirements early, actively target programs offering H‑1B.

Practical Steps to Navigate Visa Issues During the Genetics Match

1. Pre‑Application Phase: Build a Visa‑Friendly Profile

To maximize your chances in the medical genetics match:

Clarify your status early

- Are you currently outside the U.S.? On a visitor visa? In another status (F‑1, J‑1 research, H‑4, etc.)?

- Understand whether you’re already subject to any home residency requirements (e.g., prior J‑1 exchange visa).

Consider taking USMLE Step 3 early (if feasible)

- This is especially useful if you aim for H‑1B or want to keep all options open.

- Step 3 is not mandatory for the J‑1, but passing it can still strengthen your application and show readiness.

Gather documentation commonly needed for visa sponsorship

- Passport validity (at least 6 months beyond start of residency).

- Medical school diploma and transcripts.

- ECFMG certification.

- Prior visa history and DS‑2019/I‑20/I‑797 forms, if applicable.

Demonstrate stability and clarity in your personal statement

- Programs want to know you’re likely to complete the full training pathway.

- If you previously trained or lived in multiple countries, briefly and clearly outline your path to show stability.

2. Application Phase: Smart Program Selection

When screening medical genetics residency programs:

Use FRIEDA, program websites, and ERAS descriptions to confirm:

- Whether they accept IMGs.

- Their visa policy (J‑1, H‑1B, or both).

- Any additional requirements (e.g., Step 3, previous U.S. clinical experience).

Build a tiered list:

- Tier 1: Programs that fit your profile strongly and offer your preferred visa type.

- Tier 2: Programs that offer J‑1 only but are strong academically/clinically.

- Tier 3: Backup programs that sponsor visas but may be less well‑known or geographically less ideal.

Tip: Medical genetics is a smaller specialty, and many programs are relatively IMG‑friendly. However, being transparent and realistic about your visa needs is essential.

3. Interview Phase: Discussing Visa Issues Professionally

During interviews:

Be honest and concise when asked about visa needs.

Use language like:

- “I will require visa sponsorship for residency. I am currently planning for a J‑1 physician visa and understand that ECFMG is the sponsor.”

- Or, “I am eligible for H‑1B and have already passed USMLE Step 3. I am open to either J‑1 or H‑1B, depending on the program’s policies.”

Avoid sounding demanding: frame your preferences as flexible when possible, but consistent with your long‑term plans.

Ask appropriate questions, such as:

- “Does your institution currently sponsor J‑1 and/or H‑1B visas for medical genetics residents?”

- “Have recent international medical graduates in your program had any difficulties with visa processing?”

4. Ranking and Match Phase: Aligning Rankings with Visa Reality

When preparing your rank list:

Ensure your highest‑ranked programs are ones that:

- Will sponsor your needed visa, and

- Are likely to match IMGs based on prior data or your conversations.

Do not rank programs that explicitly cannot sponsor you or are unclear after repeated attempts to clarify; this can lead to serious post‑match problems.

If you’re aiming for H‑1B but are open to J‑1:

- Prioritize H‑1B‑friendly programs higher if long‑term U.S. practice is a strong priority.

- Still include strong J‑1 programs in your list for safety.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

1. Ignoring Visa Sponsorship Information

Some IMGs apply widely without checking whether a medical genetics program even supports IMGs or sponsors visas. This wastes precious applications and interview slots.

Solution:

Make visa sponsorship status a non‑negotiable filter in your program research.

2. Underestimating the Step 3 Requirement for H‑1B

A frequent mistake is planning on H‑1B but failing to pass Step 3 early enough, leaving no time for petition processing.

Solution:

If you’re serious about H‑1B:

- Plan to take Step 3 at least 6–9 months before your intended residency start date.

- Be conservative with timelines; visa processing can be delayed.

3. Misunderstanding the J‑1 Home Residency Requirement

Some applicants mistakenly believe it can be waived easily or will not apply to them.

Solution:

- Assume you will be subject to the 2‑year home requirement unless you have clear legal advice to the contrary.

- If you hope to remain in the U.S., proactively learn about J‑1 waiver options (e.g., Conrad 30, federal interest waivers, VA positions), though these usually apply after residency.

4. Not Coordinating Changes in Visa Status Between Training Steps

For example, moving from a pediatric residency on J‑1 to a medical genetics program that prefers H‑1B or vice versa without detailed planning.

Solution:

- Communicate early with both your current and future programs’ GME offices.

- Seek advice from an immigration attorney experienced with physicians if you anticipate any transitions or complex histories.

FAQs: Visa Navigation for IMGs in Medical Genetics

1. As an international medical graduate, is J‑1 or H‑1B better for a medical genetics residency?

“Better” depends on your goals:

- J‑1 is usually more available and widely accepted by medical genetics programs. It’s often the most practical path to entering U.S. GME.

- H‑1B is better if your priority is a simpler path to long‑term practice and a green card in the U.S., but only if:

- You can pass USMLE Step 3 early, and

- You target programs that explicitly sponsor H‑1B.

For many IMGs, a J‑1 for residency + waiver job post‑training is a realistic and common route.

2. Can I do both a primary residency (e.g., pediatrics) and medical genetics on the same J‑1 visa?

Yes, as long as:

- Both training programs are ACGME‑accredited and ECFMG approves ongoing sponsorship.

- Your total training time on J‑1 in the U.S. does not exceed 7 years in most cases.

- You coordinate carefully when transitioning from your primary residency to the genetics residency, ensuring continuous sponsorship.

3. Do all medical genetics residency programs sponsor visas for IMGs?

No. While many medical genetics programs are IMG‑friendly, visa policies vary:

- Some programs sponsor only J‑1.

- Some sponsor J‑1 and H‑1B.

- A few may not sponsor visas at all or only rarely.

You must check each program individually via their website, ERAS listing, or direct communication with the program coordinator or GME office.

4. If I train on a J‑1 visa, can I still stay in the U.S. after finishing my genetics residency?

Possibly, but you must address the two‑year home residency requirement:

- Options typically include:

- Completing two years in your home country after J‑1 status ends, then applying for work visas or a green card later.

- Obtaining a J‑1 waiver through:

- Conrad 30 (state‑based, often for primary care or high‑need specialties),

- Federal agencies (e.g., VA, NIH, HHS), or

- Other waiver programs that may occasionally include genetics roles.

- After securing a J‑1 waiver and a suitable job, you can transition to H‑1B or seek permanent residency with employer sponsorship.

Because post‑training immigration options are nuanced and policy‑dependent, consulting an immigration attorney familiar with physician visas is strongly recommended as you approach the end of your genetics residency.

By strategically aligning your visa plan, training pathway, and career goals, you can navigate the complexities of the U.S. immigration system and successfully build a career in medical genetics as an IMG. Your visa is not just paperwork—it is a key part of your professional roadmap. Understanding it now will give you more choices later.