Understanding the Visa Landscape for IMGs in Global Health Residency

For an international medical graduate (IMG) pursuing a global health–focused residency in the United States, visa navigation is not just a legal formality—it is a strategic part of your overall career planning. Your choice of visa category can influence:

- Which residency programs you can realistically apply to

- Your flexibility to moonlight or do research

- Your ability to participate in a global health residency track with international rotations

- Your post-residency options in global health or academic medicine

- Your long‑term immigration prospects if you want to stay in the U.S.

This IMG residency guide will walk you step‑by‑step through the major visa options, how they intersect with global health training pathways, and how to plan proactively from the moment you start preparing your application.

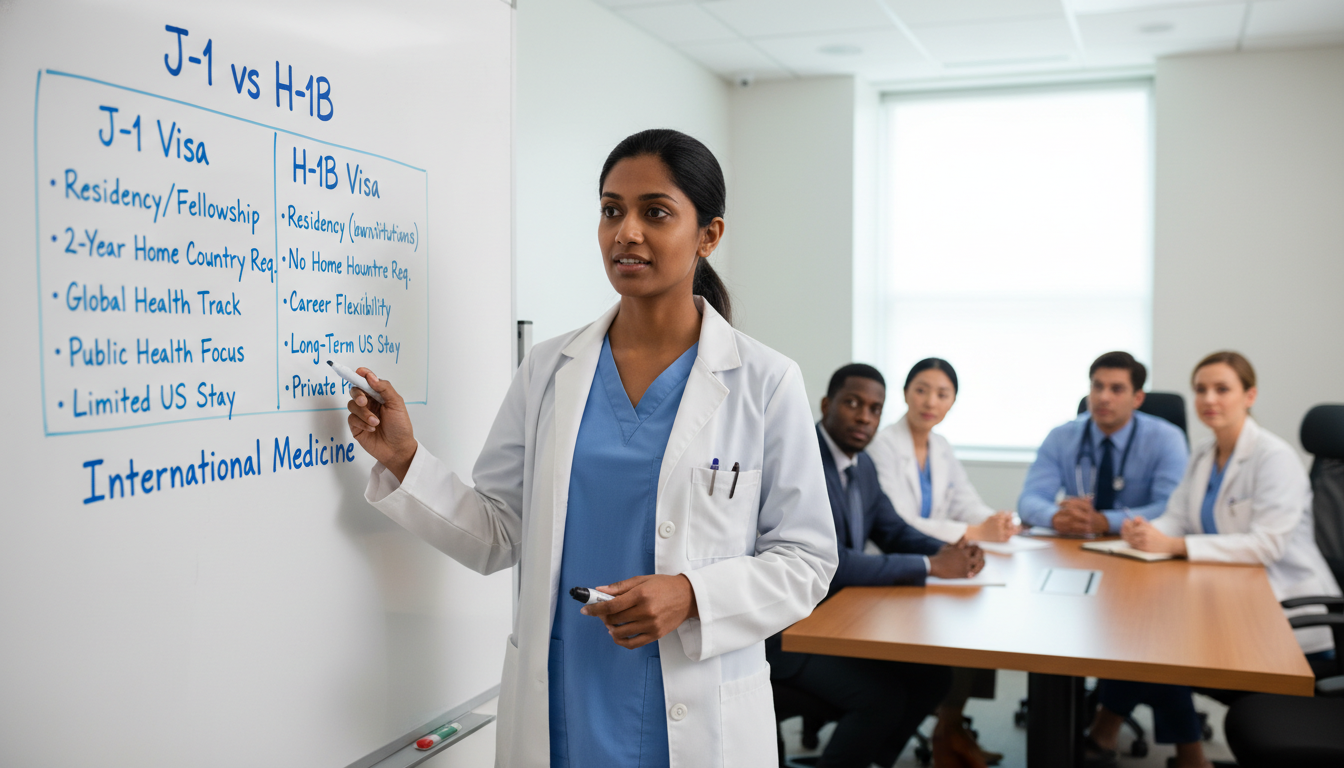

Core Visa Options for IMGs: J‑1 vs H‑1B and Others

For graduate medical education (GME) in the U.S., there are three main visa pathways IMGs typically consider:

- J‑1 Exchange Visitor (ECFMG-sponsored)

- H‑1B Temporary Worker (hospital-sponsored)

- Other less common options (e.g., F‑1 with OPT, O‑1, TN, green card holders)

Understanding the differences between these IMG visa options is crucial before you build your residency application list.

J‑1 Exchange Visitor Visa (ECFMG-Sponsored)

The J‑1 visa is the most common pathway for IMGs in U.S. residency programs.

Key features

- Sponsor: Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG)

- Purpose: Graduate medical education (residency, fellowship)

- Duration: Usually up to 7 years total for clinical training (residency + fellowship), renewed annually

- Two‑Year Home Residence Requirement (HRR):

- After completing training, you must return to your home country (or country of last permanent residence) for two years OR

- Obtain a J‑1 waiver (such as Conrad 30, academic research waiver, federal agency waiver, or hardship/persecution waiver) before moving to another U.S. status (e.g., H‑1B or permanent residence)

Advantages for IMGs

- Widely accepted by residency programs; many programs only sponsor J‑1

- Centralized process through ECFMG; programs are familiar with the steps

- Often easier and faster to obtain than H‑1B for residency start dates

- No requirement that your medical school be in a specific country

- ECFMG provides structured oversight, including guidance on compliance

Limitations

- Two‑year home residence requirement can complicate long‑term plans

- More limited ability to moonlight (depends on strict program/ECFMG rules)

- You cannot “self‑sponsor”; always dependent on ECFMG and program

- Not ideal for those who want immediate transition to long‑term U.S. immigration after training without a waiver

J‑1 and Global Health

For a global health residency track, the J‑1 can be both helpful and restrictive:

- Helpful because:

- Many academic medical centers with robust global health residency tracks primarily use J‑1 sponsorship

- J‑1 exchange program aligns conceptually with international medicine and “training then returning home” missions

- Restrictive because:

- After training, J‑1 HRR may limit your ability to stay in the U.S. for global health research, academic roles, or public health work unless you secure a waiver

- Waiver jobs are usually in underserved areas within the U.S.; not all are aligned with global health as a specialty, though some safety‑net hospitals serve “global health at home” populations

If your long‑term plan includes significant time working in your home country or region after training, the J‑1 requirement may align well with your goals. If you wish to build a U.S.-based academic or policy career in global health, you’ll need an early strategy for J‑1 waiver and later immigration steps.

H‑1B Temporary Worker Visa for Residency

The H‑1B is a work visa for “specialty occupations” that some residency programs sponsor for IMGs.

Key features

- Sponsor: Hiring institution (e.g., teaching hospital or university)

- Duration: Up to 6 years in total (including any previous H‑1B time), usually issued in 3‑year increments

- No two‑year home residence requirement after residency

- Often viewed as “dual intent”–friendly, meaning you can pursue a green card while on H‑1B

Advantages for IMGs

- No mandatory return to home country after training

- Can transition more easily into post‑residency H‑1B employment in the U.S.

- May facilitate long‑term plans for U.S. academic medicine, public health, or global health leadership roles

- In some situations, may allow somewhat more flexibility for moonlighting (subject to institutional and state restrictions)

Limitations

- Not all residency programs sponsor H‑1B, and some explicitly do not, especially community programs or smaller hospitals

- Requires passing USMLE Step 3 before H‑1B petition can be filed for clinical residency roles

- Can be more administratively and financially burdensome for the employer (legal fees, filing fees), so programs may reserve H‑1B sponsorship for exceptional candidates or specific needs

- You must already be ECFMG certified before residency start, and your medical degree and license eligibility must meet H‑1B requirements

H‑1B and Global Health

For a global health residency track, H‑1B can provide long‑term flexibility:

- Easier pathway to remain in the U.S. for:

- Academic global health positions

- Positions with NGOs, policy institutes, or global health research centers

- Additional fellowships (if sponsored) in areas like infectious disease, global health equity, or health policy

- But you must ensure:

- The residency program both supports global health training and sponsors H‑1B

- International electives are allowed under H‑1B (most often yes, if part of the ACGME-approved curriculum and correctly documented)

Because fewer programs sponsor H‑1B, IMGs aiming for global health should carefully research where H‑1B is an option and be realistic about competitiveness.

Other Visa Paths IMGs Should Know

While J‑1 vs H‑1B will be the main decision for most IMGs, you may encounter other possibilities:

F‑1 Student Visa (With or Without Optional Practical Training)

Some IMGs already in the U.S. for research, MPH, or other graduate degrees are on F‑1 visas.

- Residency itself typically cannot be done under F‑1; you will change to J‑1 or H‑1B

- F‑1 Optional Practical Training (OPT) sometimes supports a short transition post-graduation (e.g., for research employment or pre‑residency clinical research), but is not a long‑term training solution

- For those exploring global health through an MPH or research fellowship before residency, F‑1 can be part of the path but is not the endpoint for clinical training

O‑1 Extraordinary Ability

Rare but possible for IMGs with outstanding achievements (e.g., major publications, international awards).

- More often used for research or faculty roles than for standard residency

- Could be relevant after residency if you build a strong academic global health profile

- Does not carry the same HRR constraints as J‑1, but the evidentiary standard is high

TN (for Canadians/Mexicans), E‑2, and Green Card Holders

- TN status (for Canadians and Mexicans) may apply in some non-physician roles or research positions, but not typically for clinical physician residency

- E‑2 treaty investor or other categories may apply if your family has specific business arrangements; rare and complex for residency contexts

- If you are already a lawful permanent resident (green card holder), you do not need a separate residency visa—your training path is similar to U.S. graduates, though ECFMG and licensing requirements still apply.

Strategic Choice: J‑1 vs H‑1B for a Global Health Career

Choosing between J‑1 and H‑1B is not just a technical immigration question; it is a career strategy decision. For an IMG pursuing global health, consider the following dimensions.

1. Your Long‑Term Geographic Plan

Ask yourself:

- Do I see my primary long‑term career base in:

- My home country/region?

- The United States?

- A hybrid career moving between both?

Scenario A: You plan to return and build in your home country or region.

- J‑1 aligns naturally:

- U.S. training → return home to strengthen local health systems, lead global health collaborations, or work with international NGOs based there

- Two-year home residence requirement is consistent with your goals

- H‑1B may still work, but your long-term need to remain in the U.S. is less critical

Scenario B: You plan to build a U.S.-based academic or policy career in global health.

- H‑1B is usually more favorable:

- No J‑1 HRR barrier to staying for post-residency academic, policy, or research roles

- Easier to move into faculty positions at global health centers, U.S.-based NGOs, or governmental agencies

- J‑1 is still possible, but you must plan early for:

- J‑1 waiver options aligned with underserved or safety‑net settings

- Later transition to H‑1B or permanent residence

2. Program Availability and Competitiveness

Many programs, even those with international medicine or global health residency tracks, prefer J‑1 sponsorship because it is standardized and widely understood.

Reality check for H‑1B:

- Only a subset of programs sponsor H‑1B for residents

- These are often:

- Large academic institutions

- Programs accustomed to hiring IMGs into faculty and research roles

- High‑volume hospitals with experienced legal teams

- Competition can be intense; you must have:

- Strong exam scores (including Step 3 completed early)

- Solid research or leadership experience, ideally including global health exposure

- Excellent letters and a clear narrative aligning your career with the program’s mission

For many IMGs, the practical path is to be open to both J‑1 and H‑1B, but to understand where each is realistic and how each affects later choices.

3. Timing and Examination Strategy

If you are strongly oriented toward H‑1B, adjust your exam timing:

- Plan to take and pass USMLE Step 3 as early as possible (often before rank order lists are due, or at least before programs must decide sponsorship)

- Be ready to show concrete evidence of Step 3 scheduling or results during interviews

- For J‑1, Step 3 is not required for visa sponsorship (though it still helps your residency application overall)

Late Step 3 can limit your H‑1B possibilities simply because programs don’t have time to file your petition before the start of training.

4. Flexibility for Global Health Rotations and International Work

Both J‑1 and H‑1B can support global health residency tracks, but programs must structure international rotations carefully:

- Rotations must be part of ACGME-approved curricula

- They should be time‑limited and educationally justified

- Proper documentation and permission must be filed with ECFMG (for J‑1) or the institution’s legal office (for H‑1B)

When interviewing, ask:

- “How do your international rotations work for residents on J‑1 or H‑1B?”

- “Have previous IMGs on J‑1 or H‑1B successfully participated in the global health residency track?”

This helps ensure that visa status will not silently limit your participation in key global health experiences.

Step-by-Step Visa Navigation During the Residency Application Cycle

To integrate visa navigation into your overall residency application timeline, think in phases.

Phase 1: Pre-Application Planning (12–18 Months Before Match)

Clarify your goals

- Define your global health career vision:

- Academic global health or implementation science?

- Clinical work in low‑resource settings?

- Policy and advocacy?

- Decide your preliminary preference: J‑1 vs H‑1B, knowing you might need flexibility

Research program policies

- Use:

- Program websites (visa sponsorship sections)

- FREIDA (AMA) or similar databases

- Email program coordinators if information is unclear

- Specifically ask:

- “Do you sponsor ECFMG J‑1 visas for residents?”

- “Do you sponsor H‑1B visas for residents, including IMGs?”

- “Do IMGs on J‑1/H‑1B participate fully in your global health residency track?”

Build a spreadsheet categorizing programs by:

- Global health emphasis (track, pathway, certificate, or strong global health faculty)

- Visa policies (J‑1 only, J‑1 and H‑1B, rare or no sponsorship)

- Historical acceptance of IMGs

Plan examinations

- For potential H‑1B:

- Map out USMLE Step 3 timeline

- Aim to have results ready by the time programs make ranking decisions

- Regardless of visa:

- Prioritize strong Step 1/Step 2 CK (and OET/TOEFL if needed)

Phase 2: Application and Interview Season

Apply strategically

- Use your research to:

- Target programs with both global health opportunities and compatible visa options

- Maintain a realistic range of program competitiveness

- In your personal statement and interviews:

- Highlight your commitment to international medicine and underserved populations

- Show how your global perspective benefits their residency community

Discuss visas professionally

During interviews or follow-up emails:

- It is acceptable to ask:

- “Can you confirm what residency visa options you support for IMGs?”

- “Are there any limitations for residents on J‑1 or H‑1B in participating in your global health track?”

- Frame this as logistical planning, not a demand:

- You are gathering information to ensure compliance and success

Phase 3: Rank List and Match

When finalizing your rank list:

- Balance:

- Program quality and fit

- Global health opportunities

- Visa sponsorship reality

- If you strongly prefer H‑1B but have multiple excellent J‑1-only programs high on your list, be explicit with yourself about:

- Your willingness to accept J‑1 if matched

- Your plans for dealing with the J‑1 two‑year rule later

Phase 4: Post-Match Visa Processing

Once you match:

- Your program will initiate:

- ECFMG J‑1 sponsorship process or

- H‑1B petition preparation (with institutional legal counsel)

- You must:

- Provide necessary documents quickly (diplomas, ECFMG certification, passport, DS‑2019 or I‑797 documents, etc.)

- Pay required fees (if any are your responsibility; many J‑1 fees are borne by the trainee, H‑1B fees commonly by the employer, but policies vary)

- Attend your visa interview at the U.S. consulate if you are outside the U.S.

For global health track participants, ask early in PGY‑1:

- “At what point do residents generally join the global health pathway?”

- “Are there any visa-related steps I should take in advance of international rotations (e.g., ECFMG endorsement for J‑1, travel signatures, etc.)?”

Post-Residency: Navigating J‑1 Waivers, H‑1B Transfers, and Global Health Careers

The residency visa you choose will shape your post-training pathways in global health.

If You Train on a J‑1 Visa

You will confront the two‑year home residence requirement at the end of training.

Main options:

Fulfill the 2-year requirement

- Return to your home country or country of permanent residence

- Work in clinical practice, academia, or public health

- Continue involvement with U.S. collaborators on global health projects

- Later, apply for another U.S. visa or green card as permitted by your career path

Seek a J‑1 Waiver

Common routes:

- Conrad 30 Waiver (state-based)

- After training, work in a designated underserved area in the U.S. for a set number of years (often 3 years full-time)

- Typically in primary care, psychiatry, or other needed specialties

- While not always “global health” in the international sense, these jobs often serve diverse immigrant or refugee populations, aligning with “global health at home”

- Federal agency waivers

- For roles serving critical needs (e.g., in VA system, HHS, or other federal agencies)

- More specialized and competitive

- Academic or clinical research waivers

- Academic institutions can sometimes sponsor for physicians whose work is in the national interest, including specialized global health research

- Hardship or persecution waivers

- Based on individual circumstances, complex and heavily evidence-based

Once you secure a waiver, you often transition from J‑1 to H‑1B for your waiver service job. This can then lead, later, to permanent residence.

Strategic advice for global health–oriented IMGs on J‑1:

- Use residency and fellowship to build:

- Global health research output

- Expertise in high‑need conditions or populations

- Relationships with institutions that may later sponsor research or academic waivers

- Consider waiver jobs that:

- Serve vulnerable populations

- Allow continued involvement in global health research or telehealth programs

- Position you well for eventual academic or leadership roles

If You Train on an H‑1B Visa

After residency (and possibly fellowship), your primary considerations are:

- Total H‑1B time used (you cannot exceed 6 total years without special circumstances like pending green card applications)

- H‑1B transfer to a post‑residency employer (academic center, hospital, NGO, etc.)

- Green card planning, if your long‑term plan includes staying in the U.S.

Global health–relevant paths after H‑1B residency:

- Academic global health divisions at major universities

- Infectious disease, tropical medicine, or health equity fellowships (if visa sponsorship is available)

- Joint appointments with schools of public health or global health institutes

- Work with international agencies or NGOs that maintain U.S. offices (and can sponsor H‑1B or support green card petition)

Visa navigation does not end with residency; it shapes your ability to launch the global health career you envisioned when you applied.

Practical Tips to Strengthen Your Visa and Global Health Strategy

To make your IMG residency guide actionable, here are concrete steps you can implement now.

1. Document Your Global Health Commitment

Build a portfolio that supports both residency selection and later visa/waiver applications:

- Clinical or volunteer work in low‑resource settings

- Research projects on global health, infectious disease, maternal health, health systems, or migration health

- Presentations or publications related to international medicine

- Leadership roles in global health student groups, NGOs, or community organizations

2. Communicate Clearly with Programs

From application through training:

- Be honest and professional about your visa status and needs

- Clarify whether you are open to J‑1, prefer H‑1B, or must have H‑1B (for example, due to family immigration plans)

- During training, keep your program informed about any planned international activities, ensuring compliance with your residency visa conditions

3. Engage Institutional Resources Early

Make use of:

- Your institution’s GME office

- International office (for travel and status questions)

- Legal/immigration services (often free or low‑cost for residents)

- Global health faculty mentors who understand how previous IMGs navigated visas

4. Think Two Steps Ahead

Visa strategy is like chess: always look ahead.

- If on J‑1:

- Start thinking about waiver paths by mid-residency, especially if you plan to remain in the U.S.

- If on H‑1B:

- Track your total H‑1B time, and discuss green card timing with potential employers early in your post-residency job search

- Maintain flexibility by:

- Avoiding unnecessary overstays or lapses in status

- Keeping detailed records of your training, research, and service for future petitions

FAQs: Visa Navigation for Global Health–Oriented IMGs

1. Is it harder to get into a global health residency track as an IMG due to visa issues?

Not necessarily. Many global health residency tracks actively recruit IMGs for their international perspective. The main challenge is that some programs only sponsor J‑1 and a smaller number support H‑1B. As long as your visa expectations align with program policy, your IMG status alone is not a barrier—your clinical and academic profile matter much more.

2. If I want to work in global health long term, should I avoid the J‑1 visa?

Not automatically. J‑1 can be compatible with a global health career, especially if you plan to return to your home country or region and maintain partnerships with U.S. institutions. If your long‑term plan is to base yourself in the U.S., H‑1B provides more flexibility, but many J‑1 physicians successfully obtain waivers and later transition to H‑1B and permanent residence. The key is planning early.

3. Can I participate in international rotations or global health electives on a J‑1 or H‑1B?

Often yes, but only if the rotations are formally approved and properly documented. For J‑1, ECFMG and your GME office must approve the activity as part of your training. For H‑1B, the institution’s legal office must confirm that the work is covered under your petition. Always seek approval well in advance; do not assume short‑term international activities are automatically permitted.

4. Do I need a lawyer to navigate residency visa options as an IMG?

For the residency stage itself, many IMGs do not hire private lawyers—your program’s legal or international office usually manages J‑1 and H‑1B paperwork. However, if you have complex circumstances (previous visa denials, immigration violations, family immigration issues) or you are planning a specific long‑term immigration strategy, consulting an experienced immigration attorney can be valuable, especially later when pursuing J‑1 waivers or permanent residence.

By approaching residency visa navigation as an integrated part of your global health career planning, you can make informed, strategic choices at every stage—from exam timing to program selection to post-training pathways. As an international medical graduate interested in global health, your unique background is an asset; pairing it with a clear understanding of J‑1 vs H‑1B and other IMG visa options will help you build the international medicine career you envision.