Understanding the Visa Landscape as a Caribbean IMG in Vascular Surgery

For a Caribbean international medical graduate aiming for a vascular surgery residency in the United States, visa strategy is not a side issue—it is central to your match prospects and long‑term career. Programs know that visa sponsorship can be complex, and for a competitive field like vascular surgery, you must show that you understand the process as well as you understand your anatomy.

This article focuses on visa navigation specifically for:

- Caribbean medical school residency applicants

- Aspiring integrated vascular surgery residents

- SGU residency match–oriented students and similar Caribbean IMGs

- Those weighing J‑1 vs H‑1B and other IMG visa options

You’ll learn how to think about visa planning from M1 through the match, how to talk about visas with programs, and how to protect both your training and long‑term career in vascular surgery.

1. Big Picture: Why Visa Strategy Matters More in Vascular Surgery

Vascular surgery is small, highly specialized, and still relatively new in its integrated vascular program (0+5) format. That has major implications for a Caribbean IMG:

- Fewer positions compared to internal medicine or family medicine

- Fewer programs that routinely sponsor visas, especially H‑1B

- More scrutiny of applications, because small programs can’t “hide” a struggling resident

- High expectations in research, Step/USMLE scores, and letters from vascular surgeons

How Programs Think About Visa Sponsorship

When a program director considers a Caribbean IMG from an offshore school (e.g., SGU, AUC, Ross, Saba, etc.) for a vascular surgery residency, they usually ask:

Will this resident be able to start on time?

- Any history of visa denials?

- Clear visa category plan?

Is sponsorship administratively simple?

- University hospitals often default to J‑1 through ECFMG.

- Some academic centers offer H‑1B but may limit it to categorical surgical spots.

What is the long‑term risk?

- For J‑1: Will the 2‑year home‑country requirement affect their career trajectory?

- For H‑1B: Will the program be locked into complex renewals and legal fees?

You cannot change institutional policy yourself—but you can make yourself the least risky visa applicant possible by being prepared, informed, and organized.

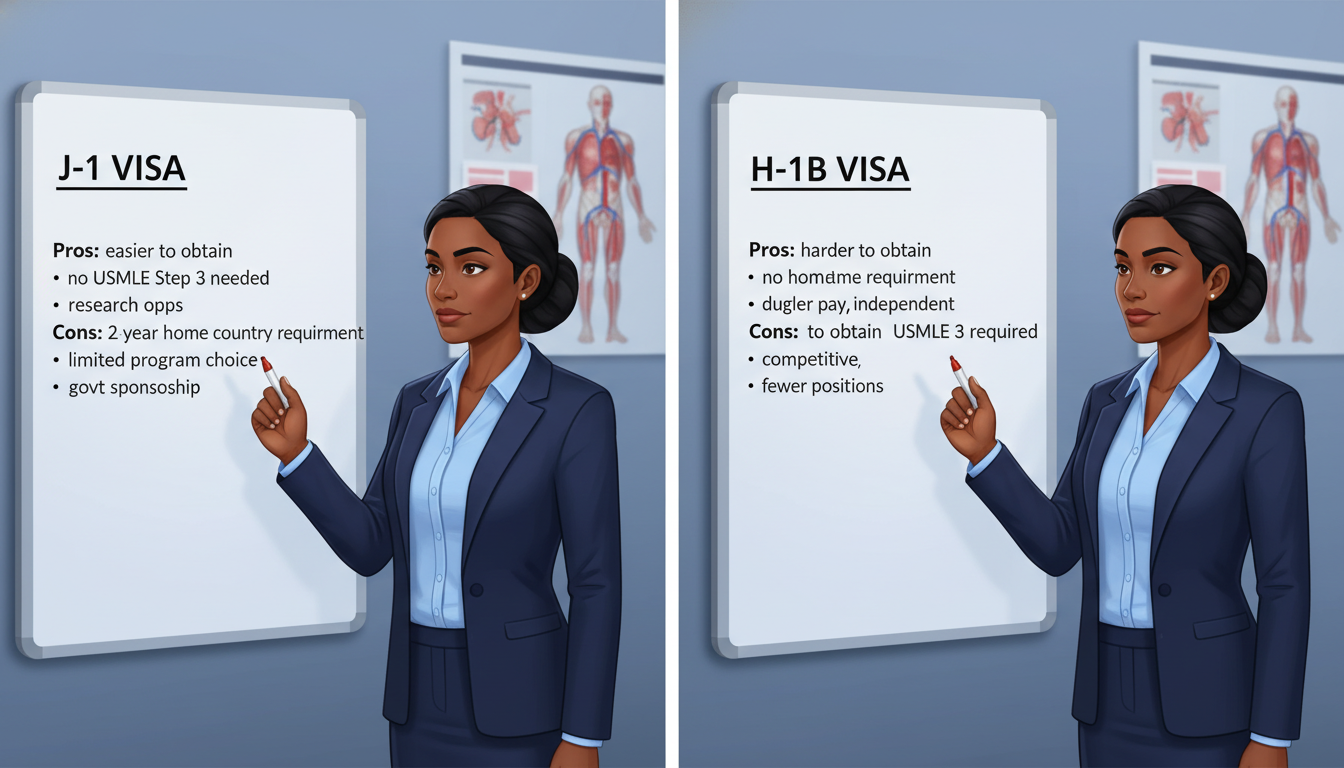

2. Core Visa Options for Caribbean IMGs in Vascular Surgery

Most Caribbean IMGs entering a US vascular surgery residency or an integrated vascular program will use one of three main pathways:

- J‑1 Exchange Visitor Physician Visa

- H‑1B Temporary Worker Visa

- Other/Transition categories (F‑1 OPT for US grads from Caribbean schools, green cards, etc.)

Let’s look at each through a vascular surgery lens.

2.1 J‑1 Visa for Vascular Surgery Residents

The J‑1 visa is the most common visa for IMGs in graduate medical education, managed through ECFMG (Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates).

Key Facts:

- Primary sponsor: ECFMG, not the hospital directly

- Purpose: Education and return of skills to home country

- Duration: Up to 7 years for clinical training (with some exceptions)

- Common in: University-based and community‑university affiliated vascular surgery programs

For a 0+5 integrated vascular surgery residency, which is 5 years, a typical J‑1 term is sufficient without extensions.

Advantages of J‑1 for Caribbean IMGs

- Most widely accepted: Many programs that accept IMGs do so exclusively via J‑1.

- Streamlined process: ECFMG guides you; institutional legal burden is lower.

- Predictability: GME offices are usually familiar with J‑1 procedures and timelines.

- Adequate duration: 5-year integrated vascular program fits within the 7-year cap.

For students focused on the SGU residency match or similar Caribbean medical school residency pathways, J‑1 often offers the highest number of potential programs that might consider your application.

Disadvantages: The 2‑Year Home‑Country Requirement

The biggest challenge: INA 212(e) – the J‑1 2‑year home‑country physical presence requirement. After J‑1 training, many physicians must:

- Return to their home country (often your passport country, not your medical school’s country) for a cumulative 2 years, or

- Obtain a J‑1 waiver (e.g., via a Conrad 30 waiver in an underserved area) before changing to H‑1B or immigrant status.

For a vascular surgeon, this has implications:

- Delayed subspecialty or academic opportunities in the US, unless you secure a waiver job.

- Limited choice of location after residency—waiver jobs may be rural or underserved communities that do not have vascular surgery positions readily available.

- Research/academic careers may be more challenging because many waiver jobs are service heavy and not research‑oriented.

For a Caribbean IMG who ultimately wants a US-based vascular surgery career, this requirement must be part of your strategic planning before you even apply.

J‑1 in an Integrated Vascular Program vs. Traditional Path

Some IMGs still follow this trajectory:

- General surgery residency

- Vascular surgery fellowship

If you are on a J‑1:

- You must fit both general surgery and vascular fellowship training within the 7‑year maximum, or argue for exception/extension (not guaranteed).

- Many vascular surgery fellowships explicitly state whether they take J‑1 holders; some prefer only J‑1 due to institutional policy, others prefer H‑1B or US citizens/green card holders.

By contrast, a 0+5 integrated vascular surgery residency keeps your training within a single 5‑year J‑1 term, which is more straightforward—but fewer programs sponsor IMGs for these positions.

2.2 H‑1B Visa for Vascular Surgery Residents

The H‑1B visa treats you as a specialty occupation worker, not an exchange visitor. For residents, it’s usually an “H‑1B for graduate medical education.”

Key Facts:

- No ECFMG sponsorship: The hospital/program becomes your H‑1B employer.

- USMLE steps required: You generally must have passed all USMLE Steps (including Step 3) before H‑1B filing.

- Maximum duration: Usually 6 years—but residency is typically 5 years for integrated vascular.

Advantages of H‑1B in Vascular Surgery

- No J‑1 home‑country requirement: You avoid the 2‑year return requirement and the complexity of J‑1 waivers.

- Easier transition to long‑term US practice: You can:

- Move directly into an attending position or fellowship on H‑1B.

- Apply for permanent residency (green card) without 212(e) constraints.

- Attractive for long training or complex career paths: If you anticipate fellowship plus research, H‑1B can offer more flexibility.

For a Caribbean IMG who wants a stable US vascular surgery career in academia or high‑tech practice, the H‑1B is often the ideal path—but it is also the hardest to secure.

Challenges of H‑1B for Caribbean IMGs

- Not all programs sponsor H‑1B, and many will explicitly say: “No H‑1B sponsorship; J‑1 only.”

- Higher institutional burden and cost:

- Filing fees and attorney costs.

- Labor Condition Application (LCA) process.

- Step 3 timing: You must complete USMLE Step 3 early, often before ranking deadlines or before the H‑1B petition window, which is tougher for Caribbean IMGs who may be completing clinical rotations and Step 2 later.

- Cap issues:

- Many university hospitals are cap‑exempt, but smaller or private hospitals may be affected by the annual H‑1B cap and lottery.

In a competitive and small specialty like vascular surgery, programs sometimes use the presence or absence of H‑1B sponsorship as an easy way to reduce administrative complexity. That means even an exceptionally strong Caribbean IMG may not receive interviews at H‑1B‑only‑reluctant programs.

2.3 Other, Less Common Pathways

For completeness, here are other statuses some Caribbean medical school graduates may have:

US Permanent Residents (Green Card Holders)

- You do not need a residency visa; you apply like a US grad.

- Programs often favor such candidates because no sponsorship is required.

US Citizens with Caribbean MD

- You are not an IMG in visa terms, though many aspects of Caribbean medical school residency competitiveness still apply.

F‑1 Students with OPT (for those who did a US degree before or after med school)

- Occasionally, F‑1 OPT can cover a short PGY‑1 period, but surgical residencies almost always require J‑1 or H‑1B for the full program.

For the typical Caribbean IMG in vascular surgery, your realistic focus will be J‑1 vs H‑1B.

3. Strategic Planning Timeline: From Caribbean School to Vascular Surgery Match

Effective visa navigation starts years before you submit your ERAS application. Below is a stepwise plan tailored to Caribbean IMGs targeting vascular surgery.

3.1 Preclinical Years (M1–M2): Laying Foundation and Understanding Constraints

- Clarify citizenship and “home country”:

- J‑1 home‑country requirement is based on nationality, not where your Caribbean medical school is located.

- Research visa policies of top vascular surgery programs:

- Bookmark program pages; create a spreadsheet:

- Columns: Accept IMGs (Y/N), J‑1 (Y/N), H‑1B (Y/N), integrated vs fellowship, academic vs community.

- Bookmark program pages; create a spreadsheet:

- Aim for top‑tier Step scores:

- Vascular surgery programs often expect:

- High performance on Step 2 CK (since Step 1 is now Pass/Fail).

- Strong scores give you more leverage for programs willing to make extra visa efforts.

- Vascular surgery programs often expect:

3.2 Clinical Years (M3–M4): Tailoring Your Profile and Keeping Visa Options Open

3.2.1 Prioritize US Clinical Experience and Vascular Exposure

- US rotations in general surgery and vascular surgery are critical.

- Aim for:

- At least one sub-internship (sub-I) in vascular surgery or closely allied surgical service at a program known to consider IMGs.

- Seek strong letters of recommendation from US vascular surgeons who understand the match and can address your readiness.

3.2.2 Decide Early on J‑1 vs H‑1B Priority

You don’t fully control which visa you’ll get—but your preference shapes your preparation:

If you prefer H‑1B:

- Take and pass USMLE Step 3 early if possible (often PGY‑1 or just before match; some programs will sponsor H‑1B from PGY‑2 onward).

- Apply heavily to programs that explicitly state H‑1B sponsorship.

- Highlight in your personal statement and interviews that you already have Step 3 (reducing the program’s risk).

If you accept or prefer J‑1:

- Focus more on securing interviews at academic centers that comfortably sponsor J‑1.

- Start reading about Conrad 30 waiver programs in your home state/country and about how vascular surgeons historically obtain J‑1 waivers.

3.3 ERAS Application Season: Communicating Your Visa Situation Clearly

When you apply to an integrated vascular program or to general surgery (with a vascular goal), clarity on your visa status is essential.

In ERAS:

- Answer all citizenship and visa-related questions accurately.

- If you have US work authorization (e.g., green card, TPS, etc.), state it clearly.

In your personal statement (optional but sometimes helpful):

- A single sentence such as:

“I am a citizen of [Country], currently on [status if any], and will require [J‑1/H‑1B] sponsorship for residency.” - This avoids unpleasant surprises and shows maturity.

- A single sentence such as:

On program websites/email:

- If a program’s stance is unclear, a concise email to the program coordinator can help:

- Include:

- Your name and status (Caribbean IMG, graduating M4).

- Your citizenship.

- One line: “I will require [J‑1/H‑1B] sponsorship.”

- Ask: “Does your program sponsor [J‑1/H‑1B] visas for residents?”

- Include:

- If a program’s stance is unclear, a concise email to the program coordinator can help:

Do this before applying widely; it can refine your application list and save money.

3.4 Interview Season: How to Talk About Visas Without Undermining Your Application

When interviewing for vascular surgery residency:

3.4.1 General Principles

Be honest but concise: Do not lead with visas; lead with your commitment to vascular surgery and your strengths.

If they ask:

- “Do you need visa sponsorship?”

- Answer:

“Yes, I will require [J‑1/H‑1B] sponsorship. I’ve reviewed your institution’s policies and understand that you [typically sponsor J‑1 / have sponsored H‑1B in the past], and I am prepared to comply with those requirements.”

Avoid sounding inflexible:

- If you deeply prefer H‑1B but the program only sponsors J‑1, you must decide whether to:

- Accept J‑1 as a viable path, or

- Not rank that program.

- If you deeply prefer H‑1B but the program only sponsors J‑1, you must decide whether to:

In a competitive field like vascular surgery, many Caribbean IMGs choose to accept J‑1 as the practical pathway and focus on long-term waiver planning.

3.4.2 Program-Specific Questions You Can (Carefully) Ask

If an opportunity arises (usually with the program coordinator or during a Q&A, not in a rushed faculty interview), you might ask:

- “Does your institution typically sponsor J‑1, H‑1B, or both for integrated vascular residents?”

- “For past residents who were on J‑1 visas, where did they typically practice after completing training?”

- “Does your institution assist with J‑1 waiver job placement or provide guidance as graduation approaches?”

These questions show that you’re thinking realistically about your future without making the conversation only about visas.

4. Post-Match Realities: Visa Processing and Long-Term Planning

Matching is only step one. For a Caribbean IMG in vascular surgery, your residency visa and long-term future need active management.

4.1 After a J‑1 Match

If you match to a program sponsoring J‑1 through ECFMG:

- Coordinate immediately with the institutional GME office:

- They will guide you to initiate your ECFMG J‑1 sponsorship application.

- Prepare documentation:

- Valid passport

- ECFMG certification

- Signed contract or offer letter from the residency program

- Proof of financial support (usually salary letter is enough)

- Proof of home-country ties if applicable

- Consular interview:

- If you are outside the US, schedule a visa interview at the US consulate.

- If you are already in the US in another status, you may switch via change of status in some circumstances.

Long-Term Strategy for J‑1 Vascular Surgeons

Begin thinking about post-residency as early as PGY‑3:

- Monitor J‑1 waiver programs (Conrad 30, federal waiver options, state-specific opportunities).

- Recognize that true vascular surgery waiver jobs can be limited:

- You may need to be flexible in location and job structure.

- Consider whether:

- You will do fellowship or academic work outside the US and then return; or

- Aim directly for a US waiver position and practice clinically.

If you later want a US academic vascular surgery role, you may transition from a waiver job to a more research‑intense center after completing your obligation and securing permanent residency.

4.2 After an H‑1B Match

If matched to a program willing to sponsor H‑1B:

Confirm Step 3 status:

- If not yet done, you may need to:

- Take Step 3 rapidly, or

- Begin on J‑1 or another status and convert later (depending on institutional policies).

- If not yet done, you may need to:

Work with the hospital’s legal office:

- They will file the I‑129 petition and related documents.

- Provide CV, diploma, ECFMG certificate, and any requested credentials promptly.

Be aware of renewals:

- For a 5‑year integrated vascular program, your H‑1B may be approved in increments (e.g., 3+2 years).

- Track expiry dates and respond quickly to renewal paperwork.

Long-Term Strategy for H‑1B Vascular Surgeons

- Consider early green card sponsorship, especially if:

- Your program or future employer has a stable academic or hospital‑based system.

- H‑1B status allows:

- Direct transition to fellowship or attending positions.

- Filing EB‑2 NIW or employer‑sponsored PERM cases without 212(e) complications.

5. Practical Tips and Common Pitfalls for Caribbean IMGs

5.1 Practical Tips

Create a “Visa & Program” Spreadsheet Early

- Columns:

- Program name

- Program type (0+5 integrated, 5+2 fellowship)

- Visa policy (J‑1 only, J‑1/H‑1B, no visas)

- Notes from coordinator emails or website

- This helps prioritize where to apply and how to allocate ERAS funds.

- Columns:

Align Your Exam Schedule with Visa Goals

- If aiming for H‑1B:

- Schedule USMLE Step 3 as early as logistically possible, ideally by late M4 or early PGY‑1.

- For J‑1:

- Make sure you’re fully ECFMG certified well before match day.

- If aiming for H‑1B:

Leverage Alumni Networks

- Connect with:

- Graduates from your Caribbean school in vascular surgery or other surgical fields.

- Ask where they matched, which visa they used, and how the institution handled things.

- Connect with:

Be Realistic but Ambitious

- Apply to:

- A mix of integrated vascular programs (if your credentials are strong) and

- General surgery programs with strong vascular exposure and fellowship pipelines.

- Visa‑friendly programs sometimes cluster in certain regions—identify them.

- Apply to:

5.2 Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Ignoring visa status until late in M4:

- Programs may screen out unclear visa applicants early.

- Assuming all academic centers will sponsor H‑1B:

- Many large centers are J‑1 only for residents, even if they sponsor H‑1B for faculty.

- Underestimating the J‑1 home‑country requirement:

- For a vascular surgery career, that 2‑year requirement can significantly delay or redirect your trajectory.

- Overestimating your ability to “convince” a program to change policy:

- Visa policy is usually institutional, not program-level. Directors often cannot make exceptions.

- Not having backup specialties or program levels:

- Vascular surgery integrated spots are extremely competitive.

- Many Caribbean IMGs succeed via:

- General surgery residency → vascular surgery fellowship

- Or, general surgery practice with a vascular focus in some contexts.

FAQ: Visa Navigation for Caribbean IMGs in Vascular Surgery

1. As a Caribbean IMG, is J‑1 or H‑1B better for vascular surgery residency?

“Better” depends on your priorities. J‑1 is more widely available and often your most realistic option for an integrated vascular program or general surgery residency. However, it comes with a 2‑year home‑country requirement that can complicate your long‑term US career. H‑1B avoids that requirement and may make future US practice and academic careers smoother, but far fewer vascular surgery programs sponsor H‑1B, and you must typically have USMLE Step 3 completed early. Many Caribbean IMGs focus on securing any strong vascular pathway with J‑1 first, then manage waivers later.

2. Do integrated vascular surgery programs commonly sponsor visas for Caribbean IMGs?

They are generally more restrictive than large internal medicine programs. Some integrated vascular programs sponsor J‑1, and a smaller subset will sponsor H‑1B. Many integrated programs do not sponsor visas at all. This is why some Caribbean IMGs pursue a general surgery residency first, especially at visa‑friendly institutions, and then apply for vascular surgery fellowships.

3. Can I change from J‑1 to H‑1B later during or after vascular surgery training?

You generally cannot change from J‑1 to H‑1B or permanent residency status until you satisfy or waive the 2‑year home‑country physical presence requirement. If you obtain a J‑1 waiver job (such as a Conrad 30 position) and fulfill the required service, you may then move into H‑1B or green card pathways. Changing mid‑residency from J‑1 to H‑1B is rare and typically blocked by 212(e).

4. Does graduating from a well-known Caribbean school like SGU help my visa chances?

It doesn’t change the legal visa rules, but it may indirectly help your SGU residency match prospects and thus your visa outcome. Some institutions are more familiar with SGU graduates and have established patterns of sponsoring J‑1 for them. Still, visa sponsorship is primarily an institutional policy issue, not a school‑name issue. Your exam scores, clinical letters, research, and clear communication about your residency visa needs are more critical than your specific Caribbean school name.

By planning your visa strategy as carefully as your exam and research strategy, you position yourself as a serious, low‑risk candidate in a small, competitive field. For a Caribbean IMG aspiring to vascular surgery, thoughtful navigation of IMG visa options, especially J‑1 vs H‑1B, can make the difference between a narrow path and a wide horizon of career possibilities in the United States.