Understanding the Landscape: Medical Genetics Residency and Visas

Medical genetics is a niche but rapidly growing specialty in the United States, offering intellectually rich practice, strong academic opportunities, and meaningful patient impact. For international medical graduates (IMGs), it can also be a particularly welcoming field: many medical genetics residency programs are affiliated with academic centers that are accustomed to sponsoring visas and supporting international trainees.

However, to reach a medical genetics residency, you must navigate complex immigration and training regulations. The intersection of the genetics match, institutional policies, and federal visa rules can be confusing—especially when you are comparing J-1 vs H-1B, preparing documents for a residency visa, and planning for long‑term training and career goals in the U.S.

This guide breaks down the key visa pathways and strategic decisions for IMGs pursuing medical genetics residency, from pre‑application planning through fellowship and early career. While laws and policies can change and individual cases vary, this article will give you a roadmap and questions to ask as you move forward.

Important disclaimer: This guide is for educational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Always confirm details with the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG), your program’s Graduate Medical Education (GME) office, and a qualified immigration attorney when needed.

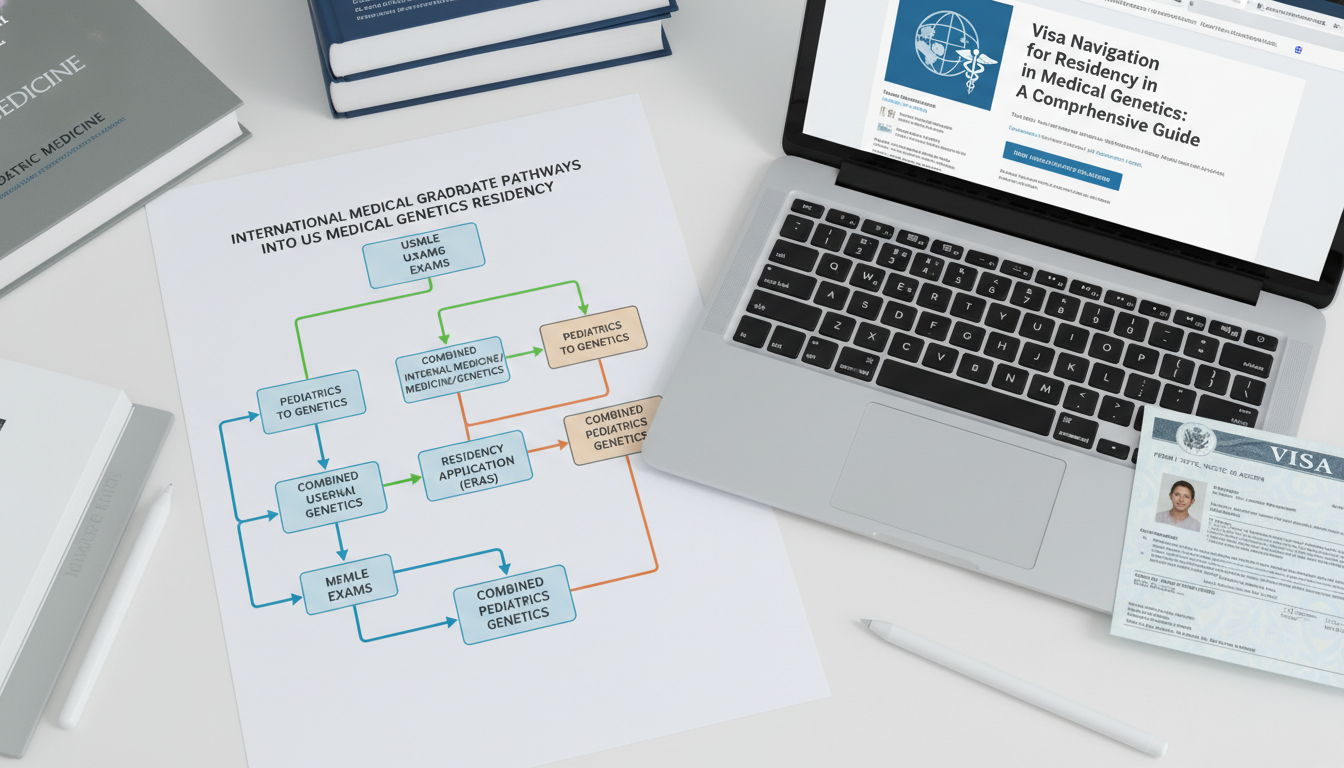

1. Overview of Training Pathways in Medical Genetics and Why Visa Choice Matters

Before looking at specific visa types, it helps to understand how training in medical genetics is structured in the U.S. This structure strongly influences which IMG visa options make sense for you.

1.1 Training Pathways in Medical Genetics

The American Board of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ABMGG) and ACGME recognize several pathways:

Combined Pediatrics–Medical Genetics (Peds‑MG) or Internal Medicine–Medical Genetics (IM‑MG)

- Typically 4–5 years total (e.g., 2 years pediatrics + 2 years medical genetics; variations exist by program).

- You match directly into a combined program via NRMP.

- Popular for those who want a broad clinical base plus genetics.

Primary Residency in Another Specialty, then a Medical Genetics Fellowship/Residency

- Example: 3‑year pediatrics residency → 2‑year medical genetics residency.

- You first match into a core residency (pediatrics, internal medicine, OB/GYN, etc.), then later apply to medical genetics training.

Medical Biochemical Genetics and Other Subspecialties

- Following medical genetics residency, you may pursue 1‑year subspecialty training.

Because one common pathway to medical genetics is via pediatrics or internal medicine residency, your visa decisions at the initial residency stage can affect your flexibility when you apply for genetics later.

1.2 Why Visa Type Matters for Medical Genetics

Medical genetics is heavily academic and research‑oriented, and many positions are based at large universities or children’s hospitals. This has implications:

- These institutions often sponsor both J‑1 and H‑1B visas, giving you options.

- Genetics often involves longer training trajectories, so you must think beyond just the first residency:

- Will my visa allow me to do a later genetics fellowship/residency?

- Is there a home‑country return requirement that affects my long‑term plan?

- Much of the genetics workforce operates in shortage areas or academic settings, which may impact your eligibility for future waivers or employment‑based visas.

In short, visa strategy for a medical genetics residency should be long‑range, not just focused on matching your first program.

2. Core Visa Options for IMGs in Medical Genetics

For graduate medical education in the U.S., the two dominant visa types are the J‑1 (Alien Physician) and the H‑1B (Temporary Worker, specialty occupation). A small minority may train on other statuses (e.g., green card, EAD via asylum, or dependent visas like H‑4/E‑2), but from a planning perspective, J‑1 vs H‑1B is the central question.

2.1 J‑1 Visa for Residency and Fellowships

The J‑1 physician visa is sponsored by ECFMG, not by individual programs directly. It is designed specifically for medical training.

Key Features

- Purpose: Graduate medical education (residency and fellowship).

- Maximum duration: Usually up to 7 years for clinical training (exceptions sometimes possible).

- Sponsorship: ECFMG holds primary sponsorship; your program must be accredited and agree to host you.

- Two‑year home‑country return requirement (INA 212(e)):

- Most J‑1 physicians are subject to this.

- After training, you must either:

- Return to your home country for a total of 2 years, or

- Obtain a J‑1 waiver (e.g., via service in a medically underserved area, government interest waiver, Conrad 30, etc.).

- Program changes/advancement: If you complete pediatrics on J‑1, then start a medical genetics residency or fellowship, you remain under J‑1 with cumulative time counting toward the total limit.

Advantages for Medical Genetics Applicants

- Widely accepted: Most academic medical centers and children’s hospitals will accept J‑1 trainees; for many programs, J‑1 is the default for IMGs.

- Straightforward for the institution: Programs do not need to deal with H‑1B caps or Department of Labor (DOL) processes.

- Reasonable for multi‑step training: For someone planning pediatrics → medical genetics → biochemical genetics, the 7‑year window is often sufficient if carefully planned.

Challenges

- Two‑year home‑country requirement:

- Can delay or complicate long‑term U.S. practice or permanent residency unless you secure a waiver.

- Genetics jobs in academic centers may or may not meet underserved‑area criteria for some waiver programs.

- Flexibility: Transitioning into non‑training roles in the U.S. immediately after your final J‑1 training can be difficult without a waiver or return home.

- Dependents: J‑2 dependents (spouse, children) may have work authorization options, but their status is also tied to your J‑1.

2.2 H‑1B Visa for Residency and Fellowships

The H‑1B visa is a work visa for specialty occupations requiring at least a bachelor’s degree; in medicine, it is typically used for residency, fellowships, and attending positions.

Key Features

- Maximum duration: Generally 6 years total (including all prior H‑1B time in any occupation).

- Sponsorship: Directly by the institution (hospital/university), not ECFMG.

- No automatic 2‑year home‑country return rule: H‑1B is not subject to INA 212(e).

- Prevailing wage requirements: Employer must meet wage regulations, which some institutions find administratively complex.

- Cap‑exempt status: Many academic medical centers are cap‑exempt, meaning they can sponsor H‑1B at any time of year and are not limited by the national H‑1B quota.

Advantages for Medical Genetics Applicants

- No J‑1 home‑return requirement: Provides more straightforward pathways into:

- Faculty positions in medical genetics

- Research roles

- Employment‑based green card categories (e.g., EB‑2, NIW)

- Direct transition to attending roles: You can often move from H‑1B residency to H‑1B faculty with fewer complications.

- Attractive for long training paths: Especially appealing if you know you will do pediatrics or internal medicine followed by medical genetics and possibly a subspecialty.

Challenges

- Not all programs sponsor H‑1B:

- Some institutions have a strict J‑1‑only policy for residents.

- This is particularly relevant when comparing pediatrics/IM programs that will lead you into genetics later.

- USMLE and licensing requirements:

- Many institutions require Step 3 completion before filing H‑1B.

- You may also need a full or training license from the state medical board.

- Time limits: A long training track (e.g., 3‑year pediatrics + 2‑year medical genetics + 1‑year biochemical genetics = 6 years) can press against the H‑1B maximum, especially if you’ve held H‑1B time for prior employment elsewhere.

2.3 Other Statuses Sometimes Used

A small number of IMGs enter medical genetics training using:

- Permanent residency (green card): Full flexibility, no training‑specific restriction.

- Dependent visas (H‑4, E‑3, L‑2, etc.): Rare, may complicate moonlighting and credentialing.

- Asylum‑based or TPS‑based work authorization (EAD): Very individual‑specific, must be carefully coordinated with GME and attorneys.

For these less common pathways, early and detailed discussion with both your lawyer and the training institution is essential.

3. Planning Visa Strategy Before the Genetics Match

Visa navigation should begin well before you interview for a medical genetics residency—or even before you apply to the core residency that is your gateway to genetics.

3.1 Matching Directly into Medical Genetics vs. Via Another Specialty

There are two broad visa‑planning scenarios:

Direct match into a combined medical genetics residency (e.g., Peds‑MG, IM‑MG):

- You will often spend all of your training at a single institution.

- One visa strategy can (in theory) cover the entire 4–5 years.

- If the program sponsors H‑1B, you may be able to align visa choice with long‑term career goals from the outset.

Two‑step path (core residency, then genetics):

- You match first into pediatrics, medicine, etc., often at one institution.

- Later, you apply to a separate medical genetics residency or fellowship, which may be at a different institution with different visa policies.

- Visa mismatches can occur, such as:

- Pediatric program only supports J‑1

- Genetics program strongly prefers H‑1B or vice versa

- You should consider future genetics visa options while choosing your initial residency.

Practical tip: When you interview for pediatrics or internal medicine, explicitly ask the PD or coordinator:

- “Do you typically sponsor J‑1, H‑1B, or both for residents?”

- “Do your residents often go into medical genetics? If so, what visas have they used for genetics training?”

- “Are there institutional restrictions on visa types for fellowships versus core residencies?”

3.2 Balancing Competitiveness and Visa Flexibility

For IMGs, especially in less IMG‑dense specialties like medical genetics, program choice is partly a numbers game. You want:

- A realistic chance to match (considering scores, research, and experience),

- A supportive academic environment for genetics, and

- A visa policy aligned with your long‑term goals.

Some trade‑offs:

- A more competitive academic center may offer H‑1B sponsorship and rich genetics exposure but be harder to match.

- A community‑focused residency might more readily accept IMGs but only sponsor J‑1; you could later face challenges if your ideal genetics program runs into J‑1 time limits or institutional preference for H‑1B.

This is where careful research, informational interviews with current residents, and transparent communication with programs are invaluable.

3.3 Long‑Term Vision: Where Do You Want to Be 10–15 Years From Now?

Medical genetics is a specialty where many physicians:

- Work in academic centers or children’s hospitals

- Conduct research, participate in clinical trials, or lead genomic programs

- Serve in leadership roles (division chief, program director, lab director)

Your long‑term aspirations influence how you think about J‑1 vs H‑1B:

- If your priority is eventual permanent residence and academic career in the U.S., an H‑1B at some stage (residency, genetics fellowship, or early faculty) may be highly advantageous.

- If you are flexible and open to:

- Returning home after training, or

- Working in an underserved area for a J‑1 waiver before entering an academic genetics role,

then training entirely on a J‑1 may fit your plans.

There is no single correct answer—only what aligns best with your goals and constraints.

4. J‑1 vs H‑1B for Medical Genetics: Deep Dive and Practical Scenarios

While we’ve covered the basics of J‑1 and H‑1B, medical genetics introduces specific nuances—especially around prolonged training, academic focus, and job market realities.

4.1 Time Limits and Multi‑Step Training

Scenario A: Pediatrics (3 years) → Medical Genetics (2 years)

- On J‑1:

- Total: 5 years, within typical 7‑year limit.

- Leaves 2 additional years for subspecialty or research training if needed.

- On H‑1B:

- Total: 5 years, within 6‑year limit, but:

- Little buffer if you need visa extensions.

- Any prior H‑1B employment in another field may reduce available time.

- Total: 5 years, within 6‑year limit, but:

Scenario B: Combined Peds‑MG Program (4–5 years)

- On J‑1:

- Comfortable fit within 7‑year limit.

- Potential for an additional 1–2 years of biochemical genetics or research if structured properly.

- On H‑1B:

- A 5‑year combined program leaves 1 year for future H‑1B training before hitting 6‑year cap (unless you start green card processes early).

4.2 Impact on Research and Academic Advancement

Medical genetics often includes substantial research and scholarly activities. The visa can affect:

- Ability to take research years or funded research time.

- Eligibility for NIH or other federal grants, some of which require certain immigration statuses.

- Timing and feasibility of adjustment of status to permanent residence.

H‑1B advantages for academic careers:

- Institutions can sponsor EB‑2 or EB‑1 petitions more straightforwardly for H‑1B faculty.

- You avoid J‑1 home‑return issues that might delay a faculty appointment in the U.S.

J‑1 considerations:

- If you secure a J‑1 waiver job in a genetics‑relevant role, you may still build an academic portfolio, especially if the employer is a teaching institution or partner hospital.

- Some academic genetics positions may be structured in underserved regions, making waiver positions possible.

4.3 J‑1 Waivers and the Genetics Job Market

Most J‑1 waiver programs (e.g., Conrad 30, federal shortage‑area waivers) focus on primary care and general specialties in underserved locations. Medical genetics is rare, highly specialized, and often based in tertiary centers, which may not be designated as shortage areas.

This creates unique challenges:

- Waiver opportunities may be limited for pure genetics positions.

- Some physicians work in a hybrid role (e.g., general pediatrics plus genetics) in a waiver‑eligible location, then transition to a full genetics role later.

- A few waiver pathways (e.g., Department of Health and Human Services clinical research waivers) may be relevant if your work is predominantly research‑based and meets specific criteria.

Anyone contemplating a J‑1 path into medical genetics should:

- Understand local and federal waiver programs early.

- Network with genetics mentors who have navigated J‑1 waivers.

- Consider whether your skill set could support a mixed clinical role in a shortage area.

4.4 Program Policy and Institutional Culture

For the genetics match, pay attention to each program’s visa stance, which often appears on their website or FREIDA listing:

- Some explicitly state: “We sponsor J‑1 only.”

- Others: “We can sponsor J‑1 and H‑1B visas for eligible applicants.”

- A few may say: “We do not sponsor visas.”

In practice, institutional culture matters:

- Academic children’s hospitals may be comfortable with H‑1B for genetics fellows but insist on J‑1 for residents due to funding or HR policies.

- A combined Peds‑MG program might have unified policies across all years, while a separate genetics division has slightly different preferences.

When you receive interview offers, prepare specific, respectful questions:

- “Can you share how your program has handled visas for recent international residents or genetics fellows?”

- “Do you anticipate any restrictions on J‑1 vs H‑1B for the duration of the combined program?”

- “Have any previous trainees encountered visa‑related obstacles when transitioning from your residency to a genetics fellowship here or elsewhere?”

5. Step‑by‑Step: Visa Navigation Through the Genetics Training Timeline

To make this more concrete, let’s walk through typical phases and highlight what to do at each stage.

5.1 Before Applying to Residency (Core or Combined)

- Clarify your end goals:

- Do you aim for a permanent genetics career in the U.S.?

- Are you open to returning home after training?

- Research programs deeply:

- Identify pediatrics, internal medicine, or combined genetics programs with:

- Strong genetics exposure (clinics, labs, faculty).

- Clear, IMG‑friendly residency visa policies.

- Identify pediatrics, internal medicine, or combined genetics programs with:

- Assess your competitiveness:

- USMLE scores, clinical experience, research in genetics or genomics.

- English proficiency and communication skills (critical for counseling‑heavy genetics practice).

- Talk to mentors and alumni:

- Ask how they navigated visas and training transitions, especially those in medical genetics.

5.2 During ERAS and Interview Season

- Tailor your personal statement:

- Highlight long‑term commitment to medical genetics.

- Show understanding of the field’s academic and research components.

- Filter programs by visa fit:

- Prefer programs that explicitly support your desired visa type.

- Keep a balanced list: some J‑1‑friendly, some H‑1B‑friendly if you are flexible.

- Discuss visa status openly when appropriate:

- Use the program coordinator as a resource for institutional policies.

- Do not let visa questions dominate the interview, but ensure clarity before ranking.

5.3 After the Match: Securing Your Visa

Once you match:

- Work closely with the GME office:

- For J‑1:

- Complete ECFMG sponsorship application early.

- Provide DS‑2019 documentation and schedule visa interview as soon as allowed.

- For H‑1B:

- Confirm Step 3, credentialing, and licensing timelines.

- Respond quickly to HR requests for documents (diplomas, transcripts, ECFMG certification).

- For J‑1:

- Plan for dependents:

- Spouses and children’s visas (J‑2 or H‑4).

- Schooling and healthcare implications.

5.4 Transitioning into Medical Genetics

As you approach the time to apply for medical genetics (or when transitioning within a combined program):

- Re‑evaluate visa time limits:

- Confirm remaining J‑1 or H‑1B time.

- If tight, explore:

- Extending J‑1 under special circumstances.

- Starting green card processes (for H‑1B) to allow extensions beyond 6 years if eligible.

- Confirm genetics program visa policies early:

- This could influence where you apply. For example:

- If you are on H‑1B and near your 6‑year limit, a program that only offers H‑1B may not be ideal unless they can support green card sponsorship quickly.

- If you are on J‑1 and near 7 years, consider whether genetics training can be structured to fit within limits.

- This could influence where you apply. For example:

- Seek mentorship:

- Genetics faculty who trained as IMGs can provide realistic insights into job prospects and waiver options.

5.5 Looking Beyond Training: First Genetics Job

As you finish your genetics residency/fellowship:

- If on J‑1:

- Actively search for waiver‑eligible roles 12–18 months before completion.

- Work with specialized immigration counsel familiar with J‑1 physician waivers.

- Negotiate job descriptions that align with waiver requirements while leveraging your genetics expertise.

- If on H‑1B:

- Look for academic or clinical genetics positions at institutions able to:

- Continue H‑1B sponsorship, and

- Potentially sponsor EB‑2/EB‑1 green card petitions.

- Start the green card process early in your attending career, especially if you have significant research or leadership potential.

- Look for academic or clinical genetics positions at institutions able to:

6. Practical Tips, Common Pitfalls, and Actionable Advice

6.1 Practical Tips for IMGs Targeting Medical Genetics

- Start visa planning early—ideally before Step 2 CK.

- Keep copies of all immigration documents (DS‑2019s, I‑797s, visa stamps, I‑94s) organized and backed up.

- Avoid gaps or unauthorized work:

- Understand what you can and cannot do during OPT, between visas, or while awaiting approval.

- Use official resources:

- ECFMG website for J‑1 rules and policy changes.

- USCIS website for H‑1B and permanent residency information.

- Invest in Step 3 early if aiming for H‑1B:

- Passing Step 3 before applying to residency increases your H‑1B viability.

- Network within the genetics community:

- Attend genetics conferences (ACMG, ASHG) virtually or in person.

- Join mentoring programs for global trainees if available.

6.2 Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Ignoring J‑1 two‑year home requirement planning:

- Do not assume a waiver will be easy to obtain, especially in a narrow specialty.

- Choosing a residency without checking its visa policy:

- You could later face barriers when applying for genetics training.

- Underestimating processing times:

- Visa delays can jeopardize your ability to start on time; apply early and follow up.

- Not consulting expert help:

- Genetics is niche, and so are some visa pathways; an experienced immigration attorney can make a major difference.

6.3 Example Profiles and Strategies

Example 1: IMG dedicated to an academic medical genetics career in the U.S.

- Strong Step scores, publications in genetics, and research experience.

- Targets large academic pediatrics programs that sponsor H‑1B and have strong genetics departments.

- Takes Step 3 before matching.

- Later matches into an H‑1B‑sponsoring medical genetics residency.

- Starts EB‑2/NIW process during late fellowship, transitions to faculty with green card pending.

Example 2: IMG open to returning home but wants high‑level training

- Plans to bring advanced genetics expertise back to home country.

- Comfortable with J‑1, including the 2‑year return.

- Matches into a J‑1‑friendly peds‑MG combined program at an academic center.

- Completes training and returns home, later collaborating internationally on research and tele‑genetics projects.

Example 3: IMG uncertain, wants maximum flexibility

- Applies broadly to both J‑1 and H‑1B‑friendly residencies.

- Chooses a program that:

- Supports both J‑1 and H‑1B,

- Has a strong track record of placing graduates into medical genetics,

- Has a clear, transparent GME office.

- Starts on J‑1 but explores potential J‑1 waiver paths during training; keeps the possibility of returning home as a viable option.

FAQs: Visa Navigation for Medical Genetics Residency

1. Is it easier to get into a medical genetics residency on a J‑1 or H‑1B visa?

Neither is universally “easier.” Many programs default to J‑1 because ECFMG handles sponsorship, making it administratively simpler. H‑1B can be more attractive to applicants but may be offered only at institutions prepared to manage the extra paperwork and wage requirements. For competitiveness, what matters more is the program’s established policy; you’ll be most successful applying to programs whose typical practice already aligns with your visa needs.

2. Can I do both pediatrics and medical genetics on the same J‑1 visa?

Yes. If you complete pediatrics and then enter a medical genetics residency or fellowship, ECFMG continues your J‑1 physician sponsorship, and the years are counted cumulatively toward the usual 7‑year maximum. This is a common pathway: 3 years of pediatrics followed by 2 years of medical genetics fits comfortably within that limit, assuming no large interruptions or additional long fellowships.

3. If I train on J‑1, can I still work in the U.S. as a medical geneticist afterward?

Yes, but you must address the two‑year home‑country return requirement. Options include:

- Returning to your home country for a total of 2 years, then coming back in another status, or

- Obtaining a J‑1 waiver by committing to work in a designated underserved area or through certain federal programs.

Because medical genetics positions are often in tertiary centers, you may need to consider jobs that combine genetics with another specialty or explore less traditional waiver paths (e.g., research‑based waivers). This typically requires careful planning and immigration counsel.

4. Do I need to pass USMLE Step 3 to get an H‑1B for medical genetics residency?

In most cases, yes. Many institutions require USMLE Step 3 for H‑1B sponsorship for any clinical resident or fellow, including those in medical genetics. Some states and institutions might have exceptions, but they are uncommon. If you are serious about pursuing H‑1B for your residency or later genetics fellowship, taking and passing Step 3 before or shortly after the match will significantly strengthen your position and options.

By understanding the interplay between medical genetics residency, the genetics match, and the major IMG visa options, you can make deliberate choices that support not only successful training but also a sustainable and fulfilling long‑term career.