Introduction: Mentorship as the Foundation of Strong Recommendation Letters

Mentorship and strong recommendation letters are deeply intertwined in medical education. Whether you are a premed applying to medical school or a medical student preparing for residency, the quality of your letters often reflects the quality of your relationships.

Recommendation letters do far more than confirm your grades or list your activities. They provide admissions committees and residency program directors with a narrative: who you are in clinical settings, how you handle stress, how you respond to feedback, and how you function as part of a team. Strong letters come from mentors who truly know you—and that requires intention, time, and strategy on your part.

This guide will walk you through how to:

- Find and evaluate potential mentors in medical school and beyond

- Build authentic, long-term mentoring relationships

- Strategically select and prepare recommenders

- Make effective, professional recommendation requests

- Maintain your mentoring network for ongoing career development and networking

By applying these strategies early, you’ll be positioned not only for exceptional recommendation letters, but for sustained growth and support throughout your medical career.

Why Mentorship Matters in Medicine and Applications

The Unique Role of Mentorship in Medical School and Training

Mentorship in medicine is not an optional “extra”—it is a core component of professional development. A mentor is more than just a letter writer; they are an experienced clinician, scientist, or educator who invests in your growth.

Key benefits of mentorship include:

Career Development and Specialty Exploration

- Clarifying whether you’re better suited for primary care, surgery, pediatrics, psychiatry, etc.

- Understanding real-world differences between related specialties (e.g., internal medicine vs. family medicine, neurology vs. psychiatry).

- Strategizing for competitive fields (e.g., derm, ortho, plastics) and understanding what it realistically takes to match.

Professional Networking and Opportunities

- Introductions to colleagues, research groups, or clinical experiences that may not be publicly advertised.

- Invitations to join quality improvement projects, committees, or student groups.

- Access to networking events, conferences, and national organizations where you can build your professional identity.

Personal and Professional Growth

- Guidance on time management, resilience, and burnout prevention.

- Honest feedback on your communication style, leadership skills, and professionalism.

- Support when you face setbacks (poor exam performance, rotation difficulties, or personal challenges).

Over time, mentors often become advocates—people who speak up for you when you are not in the room, including in selection meetings where your application is being discussed.

Why Exceptional Recommendation Letters Are So Powerful

In highly competitive admissions and residency processes, many applicants look similar on paper. This is where recommendation letters can differentiate you:

Context for Your Achievements

A mentor can explain what your performance means:- “Top 5% of students I’ve worked with over 15 years”

- “Took initiative to lead a project that improved clinic workflow”

- “Handled emotionally complex patient encounters with maturity beyond training level”

Evidence of Core Competencies

Programs look for more than intelligence and test scores. Great letters describe:- Professionalism and ethics

- Communication and teamwork

- Reliability and follow-through

- Adaptability and teachability

- Commitment to patient-centered care

Specific, Memorable Examples

The most impactful letters are narrative-driven: a mentor recounts a case you managed, how you interacted with a challenging patient, or how you responded when you made a mistake. These stories make you real and memorable to selection committees.

Strong letters come from mentors who:

- Have observed you over time

- Understand the expectations of the next stage (medical school or residency)

- Are invested in your success

Your goal is to intentionally cultivate relationships with such mentors well before any application season.

Identifying Potential Mentors Early and Strategically

Start Before You Need Recommendation Letters

Many students wait until the application cycle is imminent to think about letters. This is a mistake. The strongest recommendation letters emerge from relationships built over months or years.

Begin actively seeking mentors:

- As a premed: during research positions, clinical volunteering, or shadowing

- In preclinical years: through small-group leaders, course directors, and research projects

- In clinical years: during core clerkships and sub-internships

- During research or gap years: through principal investigators (PIs) and supervisors

Think of mentorship as ongoing career development and networking, not just a letter-writing arrangement.

Types of Potential Mentors and What They Can Offer

Diversifying your mentorship network is valuable for both your growth and your letters.

Academic Mentors (Course Directors, Professors)

- Can speak to your intellectual curiosity, study habits, and academic integrity.

- Strong choices for medical school letters, basic science or preclinical performance, and some research-focused specialties.

Clinical Mentors (Attendings, Fellows, Senior Residents)

- Observe your clinical reasoning, bedside manner, professionalism, and teamwork.

- Essential for residency applications, particularly in the specialty you’re targeting.

Research Mentors (PIs, Lab Supervisors, Clinical Research Leads)

- Can describe your critical thinking, persistence, data analysis, and scholarly output.

- Particularly valuable for research-track residencies, academic programs, and MD/PhD or physician-scientist pathways.

Longitudinal or Non-Traditional Mentors

- Long-term supervisors from jobs, community service, or leadership roles (e.g., clinic coordinator, nonprofit director).

- Can highlight leadership, reliability, communication, and commitment to service when clinical letters are limited.

How to Recognize a Strong Mentor Candidate

Look for mentors who:

- Are accessible and willing to teach—they take time to explain decisions and welcome questions

- Provide constructive feedback—they notice your strengths and also help you improve

- Have credibility—respected clinicians, faculty members, or leaders in their field

- Demonstrate professionalism and values you admire and want to emulate

Red flags include:

- Chronic unavailability, frequent cancellations

- Disrespectful behavior toward staff, students, or patients

- Lack of follow-through on promised projects or support

Choosing mentors wisely is one of your earliest professional judgment calls.

Building Meaningful, Long-Term Mentoring Relationships

Be an Active, Engaged Mentee

Once you identify potential mentors, focus on building genuine relationships instead of transactional ones.

Ways to engage:

Show up prepared

- For meetings: bring a list of questions, your CV or updated experiences, and any materials they requested.

- On rotations: read about your patients, know their labs, and ask thoughtful questions.

Follow through consistently

- If your mentor suggests an article, read it and email a brief reflection.

- If you commit to a project task, complete it on time (or communicate early if you need more time).

Demonstrate curiosity

- Ask about clinical decision-making, specialty lifestyle, practice models, and non-clinical roles.

- Seek their perspective on your evolving career interests.

Communicate Your Goals and Needs

Mentors cannot support you effectively if they do not understand your goals.

Be specific:

- “I’m exploring internal medicine and pediatrics and would value your insight on which might fit me better.”

- “I’m interested in academic medicine and would like guidance on research and teaching opportunities.”

- “I’m aiming for a competitive specialty and need help building a strong application, including letters.”

Share your timeline for major milestones (MCAT, Step exams, ERAS) so mentors can advise strategically.

Show Appreciation and Maintain Professionalism

Gratitude is not just polite; it strengthens the relationship.

- Send thank-you emails after meetings, shadowing experiences, or letters sent.

- Acknowledge their mentorship when you reach milestones (acceptances, match results, awards).

- Maintain professional boundaries: be respectful of their time and role, and avoid oversharing personal details in ways that could make them uncomfortable.

Relationships built on mutual respect and professionalism are far more likely to result in impactful Recommendation Letters and enduring support.

Choosing the Right Mentors to Write Your Recommendation Letters

Prioritize Depth of Relationship Over Title Alone

A common misconception is that you should always chase the “most famous” person. In reality, programs value specific, detailed letters over generic praise from a big name.

Ideal recommenders are those who:

- Have worked closely with you over time (e.g., supervising you on a clerkship, research project, or longitudinal clinic).

- Can cite concrete, firsthand examples of your performance.

- Understand what medical schools or residency programs value and can speak that language.

A detailed letter from a mid-level faculty member who knows you well is usually stronger than a brief, generic letter from a department chair who barely knows you.

Match Recommenders to Your Application Goals

Consider what each recommender can uniquely highlight:

For medical school:

- One or two science faculty who can attest to academic strength and readiness for a rigorous curriculum

- A clinical or volunteer supervisor who can speak to empathy, reliability, and patient care potential

- A research mentor if scholarly work is a key part of your story

For residency:

- At least one letter (often more) from attendings in the field you’re applying to (e.g., internal medicine letters for IM, surgery for surgery)

- Additional letters from other clinical rotations that showcase versatility, professionalism, and teamwork

- A research mentor if you’re applying to academic or research-focused programs

Think strategically: aim for a complementary set of letters that together showcase your intellectual ability, clinical skills, professionalism, and alignment with your chosen path.

Preparing Your Mentors to Write Outstanding Letters

Provide Clear Context and Program Information

Your mentors may write many letters each year. Make it easy for them to tailor yours effectively.

Share:

- A brief summary of what you’re applying for (e.g., “MD programs with an interest in primary care,” “categorical internal medicine residencies with strong research opportunities”).

- Any specific qualities or competencies the programs emphasize (often listed on websites).

- Application timelines, including deadlines and any early decision/early assurance programs.

For residency, indicate:

- Your specialty choice and why it fits you

- Types of programs you’re targeting (academic, community, hybrid, geographically specific)

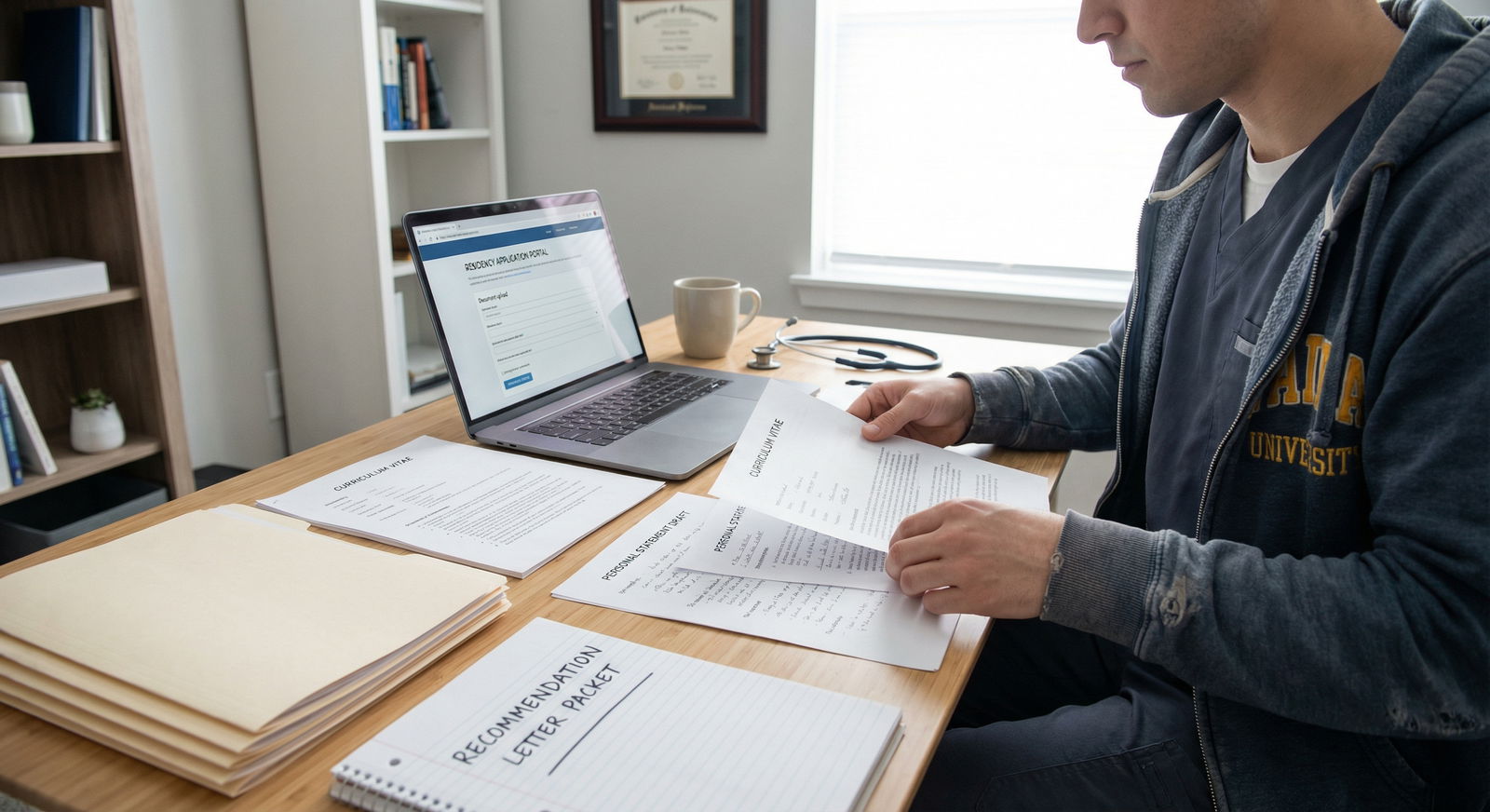

Create a Well-Organized “Letter Packet”

Deliver a concise set of documents to each recommender, ideally as a single PDF or well-organized email:

Include:

- Updated CV or resume

- Personal statement draft (even if not final)

- Brief bullet list of key experiences with that mentor:

- Dates you worked together

- Summary of work (course, research, clinic, leadership role)

- Specific projects or accomplishments they may recall

- Talking points (optional but helpful):

- 3–5 attributes you hope they can comment on, such as:

- work ethic

- clinical reasoning

- teamwork

- communication

- leadership or initiative

- 3–5 attributes you hope they can comment on, such as:

You might say:

“If possible, I’d be grateful if you could comment on my reliability, ability to work in a team, and clinical communication skills, as these are areas I’ve worked hard to develop.”

Respect Their Time and Process

Give your mentors at least 4–6 weeks to write your letter. For high-volume periods (spring for medical school, late summer for residency), earlier is even better.

Also:

- Clarify how the letter should be submitted (AMCAS, AACOMAS, ERAS, institutional portal, etc.).

- Provide any forms or links they need, already filled out with your portion complete.

- Send a polite reminder 1–2 weeks before the deadline if the letter hasn’t been confirmed as submitted.

Your organization and professionalism make it easier for mentors to advocate strongly on your behalf.

Requesting Recommendation Letters Thoughtfully and Professionally

How and When to Ask

When possible, ask in person (during a scheduled meeting or at the end of a rotation) or via a professional email if in-person is not feasible.

Aim to ask:

- Within a week or two of finishing a major rotation or project while your performance is still fresh.

- At least a month (preferably more) before the letter is needed.

A professional request might sound like:

“Dr. Smith, I’ve really appreciated your mentorship during my internal medicine rotation and the feedback you’ve given me about my growth. I’m applying to internal medicine residency programs this year, and I was hoping you’d feel comfortable writing a strong letter of recommendation on my behalf.”

This phrasing—“a strong letter”—gives them an opening to decline if they cannot enthusiastically support you.

What to Include in an Email Request

A clear email should contain:

- A brief greeting and context (“I worked with you on X rotation/project from [dates]”)

- A direct but polite request for a strong letter, mentioning what you’re applying for

- The deadline and any important notes (e.g., early deadlines, special programs)

- An offer to share your letter packet (CV, personal statement, etc.)

- Thanks for their time and mentorship

Example:

Dear Dr. Patel,

I hope you’re doing well. I had the pleasure of working with you on the inpatient pediatrics service in March and April. I learned a tremendous amount from your teaching and feedback.

I am applying to pediatric residency programs this cycle and was wondering if you would feel comfortable writing a strong letter of recommendation on my behalf. Letters are due by September 15.

I’d be happy to send my CV, personal statement draft, and a brief summary of our work together, along with any additional information that would be helpful.

Thank you very much for considering this, and for your mentorship.

Sincerely,

[Your Name]

Handling Questions and Conversations

Your mentor may want to:

- Meet briefly to discuss your goals and application strategy

- Ask why you’re choosing a particular specialty or program type

- Explore potential weaknesses in your application and how you’ve addressed them

Be honest, reflective, and open to feedback. These conversations often strengthen the letter and deepen your mentoring relationship.

Following Up, Maintaining Connections, and Managing Challenges

Following Up After the Request

After your mentor agrees:

- Send your letter packet promptly.

- Make a note of the deadline and plan to send a courteous reminder if needed.

- Once the letter is submitted, send a thank-you message acknowledging the time and effort they invested.

Later, update your mentor on the outcome:

- Medical school interviews and acceptances

- Residency interview offers and Match Day results

This closes the loop and reinforces that you see them as a long-term part of your career development and networking circle.

Considering Alternative or Supplemental Recommendations

If you lack traditional academic or clinical mentors—for example, after a non-traditional path or a period working in a different field—consider:

- Long-term employment supervisors (e.g., from scribe work, EMT roles, clinic administration)

- Leaders from community service, nonprofits, or teaching roles

- Coaches or organizational advisors who have witnessed your leadership and professionalism

These letters are often supplemental, but they can enrich your application by highlighting personal attributes like resilience, initiative, and interpersonal skills.

Preparing for and Responding to Declined Requests

A mentor may decline your request for several reasons:

- Limited time during busy seasons

- Insufficient familiarity with your work

- Feeling unable to write a strong, positive letter

While this can feel discouraging, it is actually a professional courtesy. A lukewarm or vague letter can harm your application more than it helps.

If declined:

- Thank them sincerely for their honesty and prior mentorship.

- Ask (if appropriate) what you might do in the future to be a stronger candidate for a letter.

- Move on promptly to other potential recommenders.

Your goal is not just to collect letters, but to collect the right letters from mentors who can genuinely advocate for you.

FAQs on Mentorship and Recommendation Letters for Medical Training

1. How early should I start building mentorship relationships for future recommendation letters?

Begin as early as possible. As a premed, start during research, shadowing, or long-term volunteering. In medical school, aim to identify at least one academic and one clinical mentor during your first year. Strong letters usually come from mentors who have known you for at least several months, ideally longer.

2. Is it better to have a letter from a “big name” physician who barely knows me or a lesser-known mentor who knows me well?

Always prioritize depth over prestige. A detailed, specific letter from a lesser-known mentor who has directly supervised you is far more valuable than a brief, generic letter from a famous physician who cannot speak meaningfully about your work or character.

3. Can I see or edit my recommendation letters before they are submitted?

For most centralized application systems (e.g., AMCAS, AACOMAS, ERAS), you will be asked whether you waive your right to view letters. Most advisors recommend waiving this right, as it signals to programs that your recommenders could write candidly. You should not edit the letters; instead, influence their content by providing strong materials and cultivating genuine relationships.

4. How many recommendation letters do I actually need?

Requirements vary:

- Medical school: Typically 2–3 academic letters (often including science faculty) plus sometimes 1–2 additional letters (clinical, research, or supervisor).

- Residency: Most programs require 3 letters, though some accept up to 4. At least one should be from your chosen specialty; competitive fields may expect 2–3 specialty-specific letters.

Always check each program’s specific requirements and ensure you meet their minimums while tailoring your letter set strategically.

5. How should I maintain mentor relationships after letters are submitted?

Stay in touch periodically:

- Send brief updates when you reach milestones (interviews, acceptances, match results).

- Share your gratitude and reflect on how their mentorship helped you.

- Continue to seek occasional guidance, not just when you need something.

These ongoing connections can lead to future opportunities—fellowship recommendations, collaborative projects, or career advancement—and are a key part of long-term career development and networking in medicine.

By intentionally seeking out mentorship, nurturing authentic relationships, and approaching recommendation requests strategically, you set yourself up not only for excellent letters, but for a supportive professional network that will follow you throughout your medical career.