You are halfway through college, or maybe early in medical school. Application timelines are starting to get real. Everyone around you is casually dropping lines like, “Yeah, my PI will definitely write one,” or “My premed advisor said Dr. X always writes strong letters.”

You do a mental inventory and realize:

- No PI who really knows you

- No physician you have actually worked closely with

- No professor who would recognize you outside of class

You need strong letters of recommendation. You have no obvious mentors. That is the situation.

Let me be blunt: this is fixable. But it is not fixable by sending a couple of cold emails three weeks before a deadline. You are going to build LOR relationships on purpose, step by step, with a timeline and a system.

Here is exactly how to do it.

Step 1: Know What a “Real” LOR Relationship Looks Like

Before you go hunting for mentors, you need to know what you are trying to build. A good letter of recommendation is not:

- “She attended all the classes and got an A.”

- “He shadowed me for 20 hours and seemed interested in medicine.”

Those are “verification letters.” They confirm you exist. They do not move your application.

A real, strong letter usually has:

Context of the relationship

“I have known Alex for 14 months as a research assistant in my cardiology lab.”Direct observation

Specific stories: how you handled a difficult patient, took ownership of a project, taught a junior student.Comparison

“Among the ~150 premeds I have mentored, she is in the top 5.”Projection

“I am confident he will be an outstanding medical student and compassionate physician.”

To make that possible, you need:

- Repeated contact

- Real work or responsibility

- Enough time for them to see you in different situations

So the goal is not “find someone to write a letter.”

The goal is “get myself into positions where someone can honestly write that kind of letter.”

Step 2: Audit Your Current Network (You Have More Than You Think)

You probably have more seeds than you realize. Let’s dig them out.

Write down:

Every science instructor you have had in the last 2 years

- Course name, semester, final grade

- Did you ever go to office hours? Did they ever comment on your work?

Every non-science instructor where you performed well

- Especially writing, ethics, philosophy, or any course with discussion / projects

Supervisors in any of these roles

- Clinical volunteering

- Non-clinical volunteering

- Paid work (scribe, CNA, EMT, medical assistant, barista, whatever)

- Research (even if minimal)

Advisors / program staff

- Pre-health advisor

- Honors program advisor

- Scholarship / program coordinator

Anyone who has ever complimented your work ethic or leadership

- Club advisors

- Coaches

- Lab managers

- Clinic coordinators

Now, sort them into three buckets:

Bucket A: Strong potential (already some relationship)

You have had real conversations, they know your name, you have done tangible work they supervised.Bucket B: Medium potential (they know who you are vaguely)

Good grades, maybe one or two interactions, but nothing deep.Bucket C: Weak potential (no idea who you are)

Large lecture professors, short-term shadowing, one-off events.

Your initial energy goes into A and B. You will build new relationships later. But you start where the soil is already tilled.

Step 3: Decide What Letters You Actually Need

Different paths need different letter mixes. Do not randomly chase 10 people. Be strategic.

For MD/DO applications, most schools want:

- 2 science faculty letters (biology, chemistry, physics, math)

- 1 non-science faculty letter

- 1–2 additional letters (research PI, physician, advisor, supervisor)

For premeds at the college stage, your plan should be:

- Lock in 1–2 science faculty over the next 12–18 months

- Lock in 1 non-science faculty

- Build toward 1 research or clinical supervisor

- Optional: 1 service / leadership supervisor if they know you extremely well

For early medical students (planning ahead for residency):

- Core clerkship faculty (IM, Surgery, etc.)

- Research mentor

- Possibly a sub-I attending in your chosen specialty

Point is: you are not hunting for “mentors” in the abstract. You are building towards a specific set of letter writers that covers these categories.

| Letter Type | Target Count | Source Example |

|---|---|---|

| Science Faculty | 2 | Organic Chem, Physiology |

| Non-Science Faculty | 1 | Philosophy, History |

| Research Mentor | 1 | PI or Lab Director |

| Clinical Supervisor | 1 | MD/DO, PA, RN supervisor |

Step 4: Create Relationship “Pipelines” Instead of One-Off Favors

Here is where most students mess up. They try to jump straight from:

“Hello, I was in your class two years ago”

→ “Please write me a letter in three weeks”

You are going to do this differently. You are going to build pipelines—structured paths from stranger → known → trusted → recommender.

Think of three main pipelines:

- Faculty pipeline (science and non-science)

- Research pipeline

- Clinical / service pipeline

4.1 Faculty Pipeline: From Anonymous Student to Strong Letter

You want to be that student whose name the professor brings up when someone asks, “Any strong premeds this year?”

Here is the playbook for your next 1–2 semesters:

A. Choose your target courses intentionally

At registration time:

- Pick 2–3 courses where you would be happy to have the professor write for you

- Prioritize:

- Courses with smaller sizes / discussion

- Professors with a reputation for being accessible

- Courses where you know you can excel (you need the A)

B. Make a first impression in week 1–2

- Go to office hours once in the first two weeks

- Say something like:

“I am premed and I want to actually understand this material deeply, not just pass the exams. Do you have any advice for getting the most out of your course?”

Listen. Take notes. Follow whatever they say. Then tell them later you did it.

C. Show up consistently

- Go to office hours at least every other week

- Come with:

- One content question you thought about

- One process question (study plan, connecting to bigger picture, etc.)

- Occasionally share short updates:

- “I tried your suggestion of doing problems before lecture. My quiz scores jumped.”

- “I’m volunteering at the free clinic; what we saw last week connected to your lecture on X.”

You are training them to think: “This student is serious. Teachable. Engaged.”

D. Give them something to notice

Examples:

- Start or lead a small study group and mention it when relevant

- Do an optional project or paper and actually do it well

- If they allow revision or extra credit, use it strategically and show improvement

E. Close the loop after the course ends

When the course finishes (and especially if you get an A):

Email them:

- Thank them specifically for something you learned

- Ask if you can stay in touch for advice about future courses / career steps

3–4 months later, send an update:

- New experiences, responsibilities

- How their course has been useful

After 4–12 months of that, you have a real relationship. Then you ask for a letter.

4.2 Research Pipeline: From “I Want Research” to “My PI Knows Me”

You do not need a huge R1 lab to get a strong LOR. You do need a situation where someone sees you consistently doing real work.

A. Find a research home (fast, not perfect)

Stop hunting for the “perfect” lab. You want:

- A PI or senior researcher who actually works with undergrads / students

- A project where you can contribute meaningfully in 6–12 months

- Reasonable access to the mentor (not an absentee celebrity PI)

How to get in:

- Use your network audit list: any professor whose course you liked? Ask:

“Are you accepting students in your lab, or do you know anyone who is?” - Check departmental websites for “Undergraduate research opportunities”

- Email 5–10 PIs with a short, specific message:

- Who you are

- One sentence showing you actually read their work

- What time you can commit weekly

- That you are looking for a 1+ year commitment

B. Once in the lab, behave like you want a letter from day one

This does not mean brown-nosing. It means:

- Show up on time. Every time.

- When you do not know something, ask once and then write it down.

- Take ownership of tasks:

“I noticed our data sheet has some inconsistencies. Would it be helpful if I cleaned that up this week?”

C. Increase your “letter value” over 6–12 months

Target milestones:

Months 1–3:

- Learn the basic techniques / tasks

- Be the person they do not have to worry about

- Ask 1–2 big-picture questions per month (not every day)

Months 4–8:

- Take on a mini-project, sub-analysis, or independent task

- Present a short update at a lab meeting if possible

- Meet with PI or postdoc 1:1 at least once a month

Months 9–12:

- Aim for something tangible: poster, abstract, or at least clear project contributions

- Ask for feedback on your work and respond to it

When your PI can say, “This student started from zero and became a reliable contributor who took ownership of X,” that is a good letter.

4.3 Clinical / Service Pipeline: Turn Volunteering into a Letter

Most shadowing is useless for LORs. You stood in the corner. They barely remember your name. Do not rely on that.

Instead, you want:

- Volunteer roles with responsibility

- Consistent weekly or biweekly shifts

- A named supervisor (preferably MD/DO, PA, NP, RN, or program coordinator)

Examples that can produce strong letters:

- Free clinic medical assistant / intake volunteer

- Hospital unit volunteer who actually interacts with patients

- Long-term hospice volunteer

- Scribe with 1–2 physicians consistently

- Community organization (shelter, tutoring) where you have leadership duties

Your move:

- Pick 1–2 clinical or service roles and stick with them for at least 6–12 months

- Identify one supervisor who sees you regularly (charge nurse, clinic manager, lead physician, program director)

Then:

- Ask for feedback occasionally:

“Is there anything I could be doing better on shift? I want to make sure I am really helping the team.” - Step up when there is a need: cover shifts, train new volunteers, take on unglamorous tasks without complaint

After a year, that person can easily write: “This student has volunteered with us for 100+ hours; patients and staff trust them; they handle difficult situations with maturity.”

Step 5: Work Backwards From Your Timeline

You cannot brute-force this two months before submitting AMCAS or ERAS. You need a rough schedule.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Faculty | 6 |

| Research Mentor | 12 |

| Clinical Supervisor | 9 |

Reality:

- Faculty letters: 1 semester of strong engagement + 3–6 months of follow-up

- Research / clinical letters: 9–18 months is common

So if you plan to apply:

- Medical school in June 2027:

You ideally start building these pipelines no later than early 2026. - Residency in Sept 2026:

You start eyeing potential letter-writers from the beginning of your third year.

If you are already behind, fine. You compress what you can and double down on intensity and consistency. But be honest about where you are in the pipeline. Do not pretend casual acquaintances are mentors.

Step 6: Turn Weak/Medium Relationships into Strong Ones (Deliberately)

Let’s say you are in a crunch:

- You have 6–9 months before you need letters

- You have some Bucket B people (they know your name, not much else)

- No obvious superstar mentor

Here is a 3–4 month sprint to upgrade them.

6.1 For a past professor you barely know

Subject line: “Former student seeking advice (Premed course planning)”

Email:

Dear Dr. [Name],

I was a student in your [Course, Term] class and really appreciated [specific detail: your approach to X / how you connected Y]. I am currently planning my remaining premedical coursework and was hoping to get your advice on [short, specific question].

Would you be willing to meet briefly during office hours or another time that works for you?

Best,

[Name], [Major], [Year]

Then:

- Show up prepared

- Ask 2–3 thoughtful questions (about the field, how to learn effectively, course selection)

- At the end:

“Would it be alright if I check in occasionally as I move forward? Your perspective is very helpful.”

Follow up 1–2 times a semester with updates and questions. You are building a mini-mentorship retroactively.

6.2 For a supervisor who knows you a bit

Script in person:

“I value working here and I am planning ahead for my medical school applications. I realized I would really like to grow more in this role. Is there any additional responsibility I could take on over the next few months that would be helpful to the team?”

Then do it well. And a month before you need letters:

“You have seen me grow here over the last [time period] and your feedback has been important. Would you feel comfortable writing a strong letter of recommendation for my medical school applications, highlighting my work here?”

Note: I said “strong letter” on purpose. If they hesitate or hedge, you do not use them.

Step 7: Ask for Letters the Right Way (So They Can Actually Help You)

Once you have at least a few months of real interaction (ideally more), here is the process.

7.1 Ask in person when possible

For a professor or PI:

“I have really appreciated your mentorship over the last [time period], especially [specific example]. I am applying to medical school this coming cycle and I was hoping you might be willing to write a strong letter of recommendation on my behalf.”

Then shut up and listen.

- If they say yes without hesitation: good

- If you hear: “I can write a letter” in a slow, vague tone → that is a soft no

- If they seem unsure: “I want to make sure all my letters are very strong, so please be honest—do you feel you know me well enough to write that kind of letter?”

You are protecting yourself here.

7.2 Make it as easy as possible for them

After they agree, send a follow-up email the same day with:

- Your CV / resume

- Unofficial transcript

- Draft of your personal statement

- A bullet list of things they have directly seen you do that might be helpful to mention

- Clear deadline (2–3 weeks before the real one)

- Exact submission instructions (AMCAS, Interfolio, ERAS, etc.)

Example bullet list (this part most students skip):

Potential points you have directly seen that might be useful in a letter:

- Consistently engaged in [Course] (front-row, questions in class, weekly office hours)

- Improvement from [first exam score] to [final grade] after implementing your feedback

- Led a study group that included students struggling in the course

- Connected course material to my work at [free clinic], which we discussed in office hours

You are not writing the letter for them. You are reminding them of real events. That is how you get specific, credible letters.

Step 8: Track, Follow Up, and Maintain Relationships

You need a basic system. Not a perfect app. A spreadsheet is enough.

Columns:

- Name

- Role (science faculty, non-science, PI, supervisor)

- Institution

- When you met

- Last interaction date

- Next planned interaction

- Are they a potential letter writer? (Y/N/Maybe)

- Did you request a letter? (Y/N)

- Letter submitted? (Y/N)

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| First Meeting | 1 |

| 3 Months | 4 |

| 6 Months | 8 |

| 12 Months | 15 |

Aim for:

- 1–2 meaningful touchpoints per semester per potential writer

- Zero disappearing acts (do not vanish for a year and then only appear to ask for a letter)

And thank them. Every time:

- Immediately after they agree to write

- After you know they have submitted

- After you get your outcome (acceptances, match result)

People remember students who close the loop.

Step 9: If You Are Truly Starting From Zero Right Now

Some of you are reading this with applications in the next 6–9 months and literally no relationships. That is rough, but here is the damage-control plan.

Identify 2 current or upcoming courses where you can still make yourself known strongly this term

- Go hard on office hours, engagement, performance from week 1

Pick one clinical or service activity you can do weekly and commit hard for the next 6–9 months

- Make it clear from day one you plan to stick around

- Tell the supervisor you are aiming for medical school and want to contribute meaningfully

Re-engage 1–2 past professors where you did well

- Use the advice in Step 6.1 to rebuild connection

- Even a single quality meeting plus a clear record of high performance is better than nothing

Parallel track: Talk to your prehealth or academic advisor

- Some schools offer committee letters or composite letters

- Ask exactly what they require and how they can help you with weak LOR access

This will not magically produce tier-1 superstar letters in 6 months, but it can get you above the “generic letter” line. And if your stats and activities are solid, that is often enough.

Step 10: Common Mistakes That Kill LOR Options (Avoid These)

I have watched smart students sabotage themselves in ways that were completely avoidable. Do not repeat these:

Disappearing as soon as the grade is posted

If you leave a course and never speak to the professor again, you are just a grade in a spreadsheet.Using only convenience letters

The attending you shadowed for two days, the famous PI who barely knows you. They will write useless letters.Being passive in research or volunteering

If you only do exactly what is asked and never slightly more, you blend in. Your letter will say so.Not asking for a “strong” letter

If you just say “a letter,” you invite lukewarm reports.Missing or ignoring deadlines

If you ask for a letter and then forget to follow up and clarify dates, that is on you.Trying to “script” the letter

Offering bullet points and context is good. Sending a draft and asking them to sign it is not.

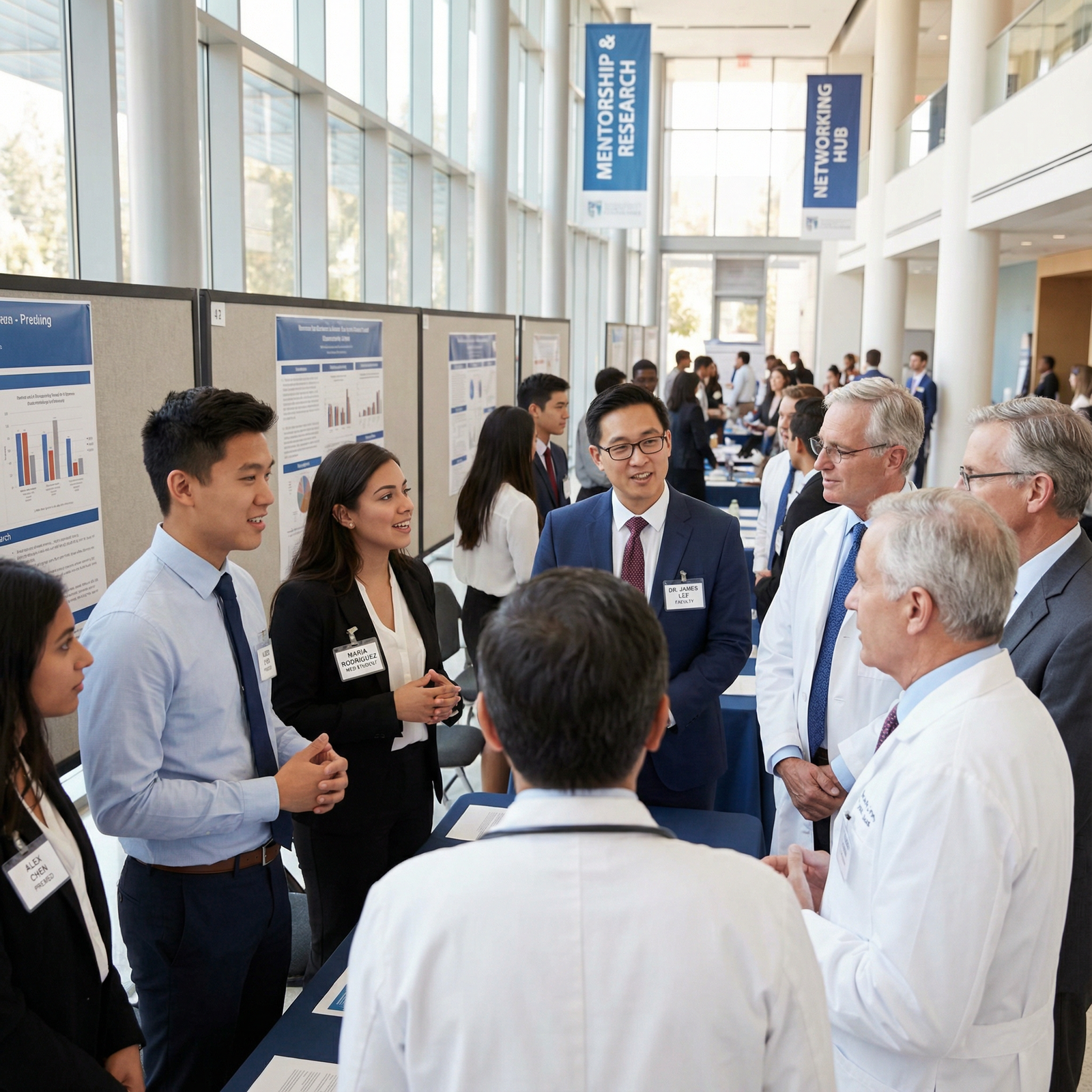

Visualizing the Whole Process

Here is what this actually looks like over time.

Final Check: Do You Have a Real Plan Now?

You should be able to answer these questions:

- Which two science faculty are you actively cultivating for letters?

- Who is your best bet for a research or clinical letter, and what are you doing this month to deepen that relationship?

- What are the exact timelines when you will ask each person, and do they have enough real interactions with you to write something specific?

If you cannot answer those, rewind and pick specific names.

Key Takeaways

- Strong letters come from time + responsibility + visibility, not from titles or fame.

- Build pipelines: faculty, research, and clinical/service, with deliberate steps from stranger to recommender.

- Ask early, ask clearly for a strong letter, and make it easy for them to say yes by doing real work they can write about.