Exploring Research Opportunities to Elevate Your Medical School Resume

Introduction: Why Research Matters for Your Medical Career

In today’s competitive medical education and residency landscape, your transcript and board scores are only part of the story. Programs also want evidence that you can think critically, work in teams, communicate clearly, and contribute to the advancement of medicine. Research opportunities in medical school are one of the most powerful ways to demonstrate all of these.

Engaging in research:

- Strengthens your medical school resume and CV for residency

- Deepens your understanding of disease mechanisms, patient care, and health systems

- Signals commitment to lifelong learning and scientific inquiry

- Opens doors to mentorship, networking, and career development across specialties

Whether you plan to pursue an academic career or primarily clinical practice, research experience can help you stand out and clarify your professional interests. This guide walks through the key types of research available to medical students, how to find and secure meaningful positions, and how to translate those experiences into a compelling, residency-ready application.

The Importance of Research in Medical Education and Career Development

Building a High-Value Skill Set Through Research

Research during medical school does far more than fill a line on your resume. It helps you develop core competencies that residency programs and future employers value:

Critical Thinking and Problem Solving

Research requires:- Formulating clear, testable questions

- Evaluating literature and identifying gaps in knowledge

- Designing methods to answer those questions

- Interpreting data in the context of existing evidence

These are the same skills you’ll use when evaluating diagnostic options or determining the best management plan for a complex patient.

Quantitative and Data Analysis Skills

Working with data builds fluency in:- Basic statistics and interpretation

- Software tools (e.g., SPSS, R, Stata, Python, REDCap)

- Understanding study design and sources of bias

Even if you don’t become a physician-scientist, you’ll need to critically evaluate research to practice evidence-based medicine.

Attention to Detail and Professionalism

From adhering to IRB protocols to accurately documenting data, research demands reliability and precision. You learn to:- Maintain research logs and databases

- Follow standardized procedures

- Respect patient confidentiality and ethical principles

These habits map directly onto safe, high-quality clinical practice.

Written and Oral Communication

Turning results into abstracts, posters, and manuscripts strengthens your ability to:- Write clearly and concisely

- Structure scientific arguments

- Present findings to peers and faculty

- Respond to critical feedback

Strong communication skills are crucial for patient counseling, interprofessional collaboration, and leadership roles.

Networking and Mentorship in Academic Medicine

Research naturally embeds you in a community of learners and leaders. As you work on projects, you’ll interact with:

- Principal investigators (PIs) and faculty mentors

- Fellow medical students and graduate students

- Residents and fellows

- Biostatisticians, research coordinators, and other team members

These connections can:

- Lead to additional research opportunities

- Help you explore specialties (e.g., matching with a cardiology mentor if you’re interested in cardiology)

- Provide strong letters of recommendation

- Offer guidance on residency choices, fellowships, and long-term career development

Demonstrating Passion, Curiosity, and Initiative

Medical schools and residency programs look for evidence that you:

- Engage in medicine beyond required coursework and clinical duties

- Take initiative to pursue questions and projects

- Commit to seeing long-term projects through to completion

Research signals intellectual curiosity and resilience—traits that distinguish excellent clinicians and leaders. Even modest research experience, when reflected on thoughtfully, can help your application stand out.

Major Types of Research Opportunities for Medical Students

Understanding the range of research options helps you target experiences that align with your interests, schedule, and career goals. You do not need to do all of these; a focused, well-executed experience is often more valuable than scattered involvement.

1. Basic Science (Bench) Research

What it is:

Basic science research focuses on fundamental biological mechanisms—how cells, molecules, and systems function and how diseases develop. It typically takes place in laboratories using cell lines, tissues, animal models, and advanced technologies.

Examples:

- Studying how a specific gene mutation alters cancer cell growth

- Investigating inflammatory pathways in autoimmune diseases

- Exploring neurophysiological changes in models of epilepsy

Best for students who:

- Enjoy lab work and controlled experiments

- Are interested in MD/PhD or physician-scientist pathways

- Have sustained time blocks (e.g., a research year, protected summer)

Pros:

- Deep exposure to scientific method and experimental design

- Opportunities for high-impact publications

- Strong foundation for future academic careers

Challenges:

- Results and publications often take longer

- Steep learning curve for lab techniques and theory

2. Clinical Research

What it is:

Clinical research focuses on patients and clinical outcomes, often involving:

- Clinical trials of medications, devices, or procedures

- Observational cohort or case-control studies

- Chart reviews and retrospective data analysis

Examples:

- Comparing outcomes of two surgical approaches for hip fractures

- Evaluating the effectiveness of a new diabetes education program

- Retrospective chart review of stroke patients with specific risk factors

Best for students who:

- Enjoy direct connection to patient care

- Want to strengthen residency applications in clinical specialties

- Need flexible hours that can be balanced with coursework or rotations

Pros:

- Clear relevance to clinical practice

- Often faster path to abstracts, posters, or papers

- Good exposure to clinical environments and teams

Challenges:

- IRB and regulatory timelines can delay start

- Data cleaning and chart review can be time-intensive and repetitive

3. Translational Research (“Bench to Bedside”)

What it is:

Translational research bridges basic science discoveries and clinical application. It often involves:

- Applying lab findings to early-phase human studies

- Developing biomarkers or diagnostic tools

- Testing new therapies derived from preclinical models

Examples:

- Moving a promising cancer drug from animal models to phase I human trials

- Developing a blood test based on molecular markers identified in the lab

- Evaluating gene therapies that target known disease pathways

Best for students who:

- Want both mechanistic and clinical exposure

- Are interested in innovation and emerging therapies

- Are considering academic medicine or industry collaborations

4. Epidemiological and Population Health Research

What it is:

Epidemiology studies the distribution and determinants of health and disease in populations. Population health research expands this to consider systems, policies, and community-level factors.

Examples:

- Using large datasets to identify risk factors for stroke in a specific demographic

- Analyzing vaccination rates by region and their impact on outbreaks

- Studying social determinants of health and hospital readmission rates

Best for students who:

- Like working with large datasets and statistics

- Are interested in public health, preventive medicine, or health policy

- May consider dual degrees (MD/MPH)

Pros:

- Strong alignment with evidence-based medicine

- Skills directly applicable to quality improvement and policy work

- Many projects are feasible remotely or with flexible schedules

5. Health Services and Quality Improvement (QI) Research

What it is:

Health services research examines how healthcare is delivered, financed, and organized. Quality improvement focuses on systematically improving care processes and patient outcomes.

Examples:

- Evaluating the impact of telemedicine visits on chronic disease management

- Implementing and studying a new sepsis protocol in the emergency department

- Reducing medication errors through a new reconciliation process

Best for students who:

- Enjoy systems thinking and teamwork

- Are drawn to leadership, administration, or healthcare policy

- Want projects that can be integrated into clinical rotations

Pros:

- Direct, visible impact on patient care and workflow

- Often faster timelines for implementation and results

- Very relevant to every specialty, especially internal medicine, pediatrics, and emergency medicine

How to Find and Secure Research Opportunities in Medical School

1. Start with Your Medical School Network

Your own institution is usually the richest source of research opportunities.

Actionable steps:

Browse department websites

Look under “Research,” “Publications,” or “Faculty Interests.” Note faculty whose work aligns with your interests (e.g., cardiology, global health, medical education).Attend grand rounds and research seminars

These sessions often highlight ongoing projects. Afterward, introduce yourself briefly and express interest.Ask upperclassmen and residents

They can recommend mentors who are student-friendly and have a track record of successful student projects.

How to reach out effectively (sample email outline):

- Introduce yourself (name, year, school)

- State your interests and how you found their work

- Mention specific papers or projects that impressed you

- Briefly describe your availability (e.g., “10–12 hrs/week during this semester” or “full-time this summer”)

- Ask if they are accepting students or know colleagues who might be

Keep your email concise (8–10 sentences) and attach a one-page CV highlighting relevant skills or coursework.

2. Use Institutional Research Offices and Databases

Most medical schools have:

- An Office of Medical Student Research or Office of Scholarly Activity

- Lists of ongoing faculty projects or “research opportunity databases”

- Formal research tracks or scholarly concentration programs

Ask about:

- Funded summer research programs

- Scholarship or travel grants for conference presentations

- Guidance on IRB submissions for your own project ideas

These resources can streamline your search and provide structured mentorship.

3. Explore Summer and Dedicated Research Programs

If you have a summer between preclinical years or a planned research year, consider:

- NIH or national research fellowships

- Specialty-specific programs (e.g., American Heart Association, oncology research programs)

- University-based summer research internships (often with stipends)

These programs typically offer:

- Protected time for research

- Formal curricula on study design and statistics

- Opportunities to present at an end-of-program symposium

Apply early—deadlines often fall 6–9 months before the start date.

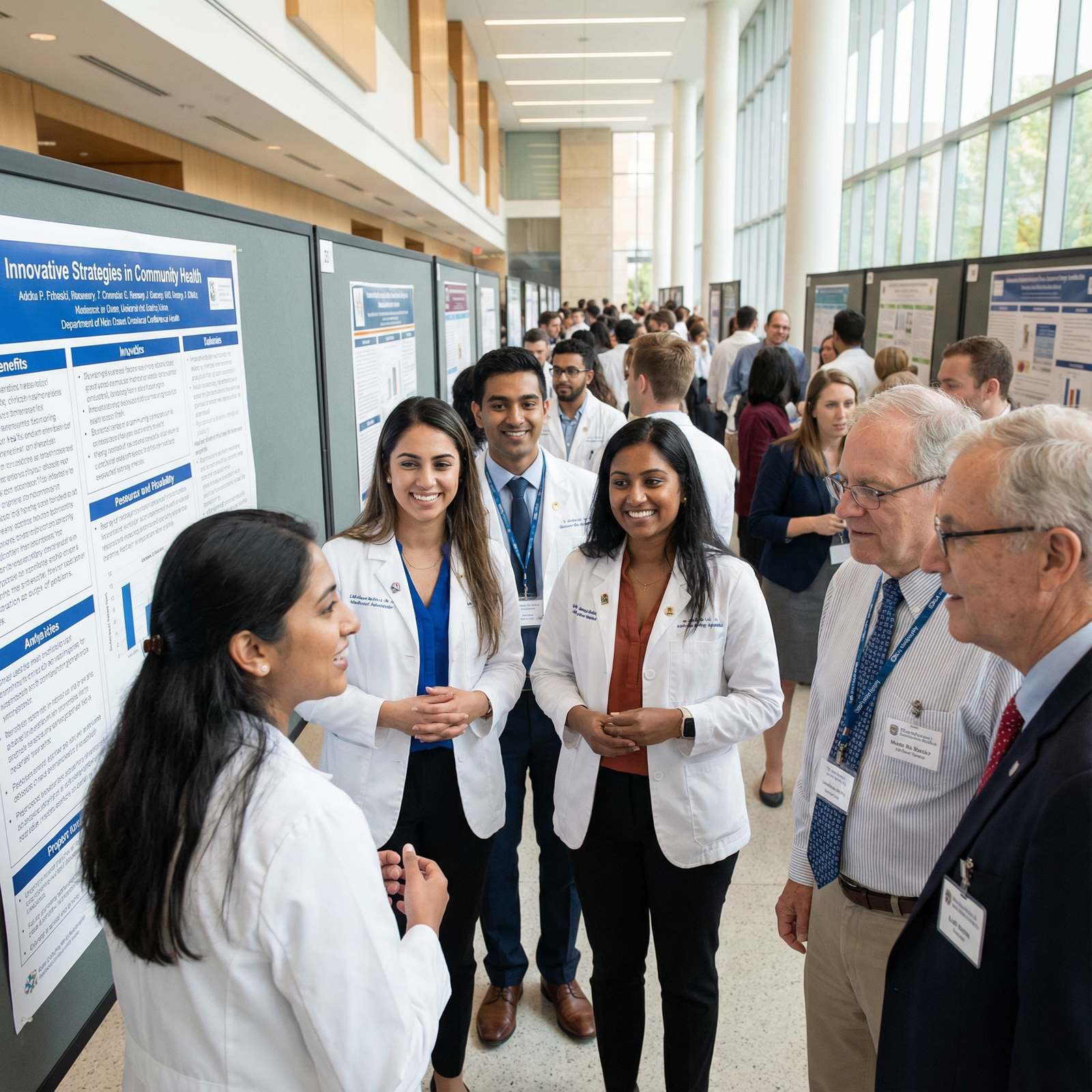

4. Attend Conferences and Research Days

Conferences are powerful venues to identify research mentors and projects:

Institutional Research Day or Student Research Day

Meet peers and faculty doing work that interests you. Ask current students how they got involved.Regional and national specialty conferences

Even as an observer, you can network and learn what questions are at the forefront of a field.

Tips:

- Prepare a 30-second “elevator pitch” about your interests and background.

- Follow up with new contacts within a week, thanking them for their time and asking about possible collaboration.

5. Leverage Online Platforms and External Institutions

If opportunities are limited at your school or you have specific niche interests, look externally:

- Academic institution websites in your city or region

- Online platforms like LinkedIn (search “clinical research fellow,” “medical student research”), professional society websites, and program directories

- Volunteer-based or remote research roles (e.g., chart reviews, data analysis, systematic reviews)

Be realistic about remote collaboration: clarify expectations, communication frequency, and authorship early.

Making the Most of Your Research Experience

1. Clarify Goals and Expectations Early

At the start of a project, have a structured conversation with your mentor about:

- Your role and responsibilities

- Expected time commitment and schedule

- Feasible goals (e.g., abstract submission, poster, manuscript)

- Authorship expectations and criteria

Documenting this in a brief email summary helps prevent misunderstandings and keeps everyone aligned.

2. Stay Organized and Document Your Work

Keep detailed records of your:

- Tasks and contributions (e.g., charts reviewed, experiments performed, data cleaned)

- Skills acquired (e.g., statistical software, lab techniques, survey design)

- Outputs (e.g., abstracts, posters, presentations, manuscripts)

Use folders on your computer or cloud storage to file:

- Drafts of abstracts and posters

- IRB documents (if you’re listed)

- Final versions of any presentations

This will make it much easier to update your resume, ERAS application, and discuss specifics during residency interviews.

3. Aim for Tangible Scholarly Products

Not every project will yield a publication, but you should actively seek opportunities to share your work:

- Abstracts and posters at local, regional, or national conferences

- Oral presentations at departmental meetings or research days

- Manuscripts (case reports, original research, review articles)

If your project stalls, ask your mentor:

- Whether there is a smaller subproject you can drive to completion

- If there are existing datasets or ongoing projects you could help finalize for dissemination

Even a well-crafted case report or educational poster can significantly enhance your research portfolio.

4. Reflect on Learning and Career Fit

Research is also a powerful tool for career development:

- Did you enjoy the research environment (pace, type of work, collaboration)?

- Did exposure to a specialty confirm or change your interest?

- What did you learn about your preferred work style?

Keep a brief reflection journal after key milestones. These reflections will provide rich material for personal statements, interviews, and future decision-making.

5. Build Long-Term Relationships and Mentorship

Even after your project ends:

- Update your mentor periodically on your progress (exams, rotations, match results)

- Offer to help with revisions or follow-up analyses

- Ask for advice when preparing residency applications or considering electives

Strong, ongoing relationships can lead to:

- Multiple projects across your years in medical school

- Powerful letters of recommendation that speak to your growth over time

- Long-term mentors who guide you through residency and beyond

How to Highlight Research on Your Medical School Resume and Residency CV

Your research experiences are only as impactful as how clearly and strategically you present them. Think about your resume as a narrative of your growth as a future physician.

1. Create a Dedicated Research and Scholarly Activity Section

On your CV or resume, include a section labeled:

- “Research Experience”

- “Research and Scholarly Activities”

- “Scholarly Work and Publications”

For each entry, list:

- Project title or concise descriptive heading

- Your role (e.g., “Student Research Assistant,” “Co-investigator,” “First Author”)

- Institution/department and location

- Dates of involvement

- 2–4 bullet points highlighting your specific contributions and skills

Example:

Clinical Research Assistant, Department of Cardiology

XYZ Medical Center, City, State | 2023–Present

- Conducted retrospective chart review of 250 patients with heart failure to evaluate 30-day readmission predictors

- Managed REDCap database and performed statistical analyses using SPSS

- Co-authored abstract accepted for presentation at the American College of Cardiology annual meeting

2. List Publications, Presentations, and Posters Separately

Create subsections such as:

- Peer-Reviewed Publications

- Manuscripts in Preparation or Under Review

- Abstracts and Conference Presentations

- Posters

Use standardized citation formats (e.g., AMA). Clearly indicate your author position (e.g., bold your name) and status (published, accepted, submitted).

3. Emphasize Transferable Skills

Beyond listing tasks, highlight skills that matter for residency and clinical practice:

- Study design and critical appraisal

- Data collection and analysis

- Statistical software proficiency

- Teamwork and interdisciplinary collaboration

- Time management and project leadership

- Scientific writing and public speaking

These can appear both in research descriptions and in a general “Skills” or “Professional Competencies” section.

4. Tailor Your Research Story for Each Application

When applying to residency:

- Emphasize projects relevant to that specialty (e.g., pediatrics research for pediatrics programs)

- Highlight leadership roles (e.g., leading a QI initiative on the inpatient service)

- Use your personal statement to connect research themes to your clinical interests

During interviews, be ready to:

- Explain your research in clear, jargon-free language

- Describe your specific role, challenges encountered, and what you learned

- Reflect honestly on what went well and what you would do differently

Using strong action verbs (“designed,” “coordinated,” “implemented,” “analyzed,” “authored”) helps convey impact and initiative.

Frequently Asked Questions About Research in Medical School

1. How early should I start looking for research opportunities in medical school?

You can begin exploring as early as your first year of medical school, but timing depends on your workload and adjustment to medical school life. Many students:

- Spend the first semester focusing on foundations and time management

- Begin reaching out to potential mentors in late M1 or early M2

- Use the summer after M1 (or between preclinical years) for more intensive research

The key is consistency and follow-through, not just starting early. A well-executed 1–2 year project is more impactful than many short, fragmented experiences.

2. Is research absolutely necessary for matching into residency?

Research is not mandatory for every specialty, but it is increasingly common and often beneficial:

- Highly competitive specialties (e.g., dermatology, plastic surgery, orthopedics, ENT, radiation oncology, neurosurgery) typically expect significant research and multiple scholarly products.

- Moderately competitive specialties (e.g., internal medicine, pediatrics, emergency medicine, anesthesiology) value research, especially if you’re aiming for academic programs.

- Less research-intensive specialties may still view research favorably as evidence of initiative and critical thinking.

If you do not enjoy research, you can still build a strong application by emphasizing clinical excellence, leadership, teaching, and community involvement, but at least one solid research or QI experience is advantageous for most applicants.

3. What if my research is in a field unrelated to my chosen specialty?

That is completely acceptable. Programs understand that interests evolve. Any well-executed research experience can showcase:

- Your ability to work in teams

- Persistence in long-term projects

- Data literacy and evidence-based thinking

When applying, draw connections between the skills you developed and your target specialty. For example, qualitative research in medical education can still demonstrate communication and systems-thinking valuable in any field.

4. I’m overwhelmed by coursework and clinical responsibilities. How can I realistically balance research?

Balancing research with medical school life and exams is challenging but achievable with planning:

- Be honest with mentors about your time (e.g., “5 hours/week during clinical year except on call weeks”).

- Choose projects with flexible timelines (e.g., chart review, survey-based, or QI work) during busy rotations.

- Use lighter rotations or elective time to intensify your research efforts.

- Block off dedicated weekly time on your calendar for research, even if it’s only 1–2 hours.

If at any point you feel overcommitted, communicate early with your mentor to adjust your role rather than disappearing or missing deadlines.

5. What if my project doesn’t lead to a publication—does it still help my resume?

Yes. Not every project results in a published paper, and programs know this. You can still:

- List the research experience with a clear description of your contributions

- Highlight any internal presentations, research days, or quality improvement outcomes

- Emphasize skills gained (data analysis, literature review, collaboration, IRB experience)

If a publication is unlikely, ask your mentor if there are:

- Smaller follow-up analyses you could complete

- Opportunities to turn your work into a poster, educational handout, or internal report

What matters most is your engagement, reliability, and thoughtful reflection on what you learned.

Engaging in research during medical school is one of the most effective forms of resume building and career development. By understanding the different types of research, strategically seeking opportunities, and presenting your work clearly on your CV, you can transform research from a checkbox activity into a meaningful, career-shaping experience that enhances your medical education and prepares you for a successful residency match and beyond.