How Many Hours Do Physicians Work? The Real Link Between Workload, Salary, and Burnout

The life of a physician is often portrayed as prestigious and financially rewarding, but the reality behind the scenes is more complex. Physician work hours are long, unpredictable, and emotionally demanding—and these factors directly shape both physician salary and long‑term well‑being.

For medical students, residents, and early‑career doctors planning their futures, it’s crucial to understand not just “How many hours do physicians work?” but also how those hours are structured, how they differ by medical specialties, and what they mean for income, burnout, and career satisfaction.

This expanded guide takes a deeper look at:

- Typical physician work hours across specialties and practice settings

- How schedules, call, and productivity expectations affect pay

- The nuanced relationship between workload, physician salary, and burnout

- Practical strategies to balance earnings with quality of life

- Key healthcare insights for choosing and shaping your career path

Understanding Physician Work Hours: Beyond a Simple Weekly Number

When people ask how many hours physicians work, they often expect a single number. In reality, “work hours” for physicians are multifaceted and extend far beyond direct patient care.

Average Weekly Hours: The Big Picture

Surveys such as the Medscape Physician Lifestyle and Compensation reports consistently show that physicians work around 50–55 hours per week on average in the United States. However, this average hides wide variation:

- Many outpatient physicians cluster around 40–50 hours of scheduled time, plus charting and admin.

- Hospital-based physicians, surgeons, and proceduralists frequently average 55–70 hours when accounting for call, nights, and weekends.

- During training (medical school and residency), hours are often longer and more irregular than in later attending practice.

Crucially, “work” for physicians includes:

- Direct patient care (clinic, hospital rounds, procedures)

- Documentation and charting in the EHR

- Inbox messages, prescription refills, and test result follow‑up

- Phone calls with patients, families, and consultants

- Administrative duties, meetings, and quality initiatives

- Teaching, research, and committee work in academic settings

A physician with “office hours” from 8–5 may still be completing notes, answering messages, or reviewing labs late into the evening.

Work Hours by Specialty: Which Fields Work the Longest?

Different medical specialties have distinct patterns of work hours and lifestyle. While exact numbers vary by survey and practice type, some typical ranges include:

Emergency Medicine

- Often 40–50 clinical hours per week on paper (e.g., 12–14 shifts/month)

- Shift work includes nights, weekends, and holidays

- Intensity is high, and circadian disruption is common

- Nonclinical tasks can push total workload closer to 50–60 hours

General Surgery & Surgical Subspecialties (e.g., orthopedics, neurosurgery, cardiothoracic)

- Frequently 60–80 hours per week, especially in busy practices

- Early-morning rounds, full OR days, postoperative care, and call

- Case length is unpredictable; a complex case can dramatically extend the day

Internal Medicine & Family Medicine

- Many outpatient clinicians work 45–60 hours per week

- Combination of clinic, inpatient rounding (for some), call, and paperwork

- Hospitalists typically work “block” schedules (e.g., 7 on/7 off) averaging 12‑hour days during on-weeks

Psychiatry

- Often 40–50 hours per week, with a mix of inpatient and outpatient work

- Fewer emergencies; call is often lighter than in surgical or acute care specialties

- Work is emotionally intense, though physically less demanding

Dermatology, Radiology, Pathology, and Some Lifestyle‑Oriented Subspecialties

- Frequently report 35–45 hours per week

- More predictable schedules, fewer nights and weekends

- Some radiologists, especially teleradiologists, may work evenings/nights but with more control over total hours

These ranges are not rigid. Within every specialty, you’ll find physicians who intentionally work part‑time, build niche practices, or negotiate more flexible schedules to manage burnout or personal priorities.

Key Factors That Shape Physician Work Hours

The Impact of On‑Call Responsibilities

On‑call duties are one of the biggest drivers of long physician work hours—and one of the most misunderstood aspects of physician schedules.

What does “on call” actually mean?

Being on call generally means you are responsible for:

- Managing emergencies or urgent consults

- Admitting new patients or taking cross‑coverage

- Fielding after‑hours calls from nurses, patients, or other providers

- Coming into the hospital at night or on weekends if needed

How call works varies significantly:

- In-house call: You remain in the hospital for a defined period (e.g., 24 hours). Common in surgery, OB/GYN, and some hospitalist roles.

- Home call: You are off-site but available by phone and able to return quickly if necessary. Common in many specialties, especially in community settings.

Call can add substantial effective hours to a physician’s week:

- A surgeon might have four or more 24‑hour call shifts per month, turning a 50‑hour week into 70+ when factoring in night work and post‑call fatigue.

- A primary care physician covering their own patients’ after‑hours calls may have interrupted evenings and weekends, even if actual call volume is modest.

As a result, two physicians with the same “contracted” schedule could have very different real‑world workloads depending on call expectations.

Geographic and Practice‑Setting Variability

Urban vs. Rural:

- Urban physicians often see higher patient volumes, especially in busy hospital systems or large group practices. This can translate into more clinic sessions, more admissions, and more complex cases.

- Rural physicians may have fewer daily patient encounters but broader scope of practice—and lighter specialist backup. They might take more frequent call, but daily schedules can be more flexible.

Academic vs. Community Practice:

- Academic physicians typically divide time among clinical work, teaching, research, and administration. Clinical hours may be fewer, but the “total work week” can still be heavy due to meetings, scholarly work, and mentoring responsibilities.

- Community physicians may spend a larger proportion of time on direct patient care and revenue‑generating activity, with shorter academic or administrative commitments.

Employed vs. Private Practice:

Hospital- or system-employed physicians often have:

- More standardized schedules

- Less direct control over productivity targets

- More predictable income but sometimes higher nonclinical burden (meetings, metrics, EHR requirements)

Private practice physicians may:

- Set more of their own hours

- Work longer early in their careers to build a patient base and income

- Gain more autonomy over time, sometimes reducing hours later in life

How Workload Influences Physician Salary and Income Potential

Physician salary is closely tied to workload—but the relationship is neither simple nor purely linear. Hours are only one part of how physicians are compensated.

Salary by Specialty and Hours: Not All Time Is Equal

According to recent compensation surveys (e.g., Medscape 2023), broad patterns remain consistent:

Primary care physicians (e.g., family medicine, general internal medicine):

- Average around $250,000–$300,000 per year, often working 45–60 hours/week

- Lower pay per hour compared to many procedural specialties

Specialists (e.g., cardiology, gastroenterology, orthopedics, radiology):

- Commonly earn $400,000+ per year

- Some high‑earning surgeons and proceduralists exceed $600,000–$800,000+ in busy practices

- Higher income often comes with longer and more intense work weeks

“Lifestyle” specialties (e.g., dermatology, some radiology roles):

- May earn $350,000–$450,000+ with 35–45 hours/week and relatively few nights/weekends

- Represent some of the most favorable income‑to‑hours ratios

A key takeaway: hours worked matter, but the type of work also matters. Procedural volume, payer mix, practice efficiency, and overhead costs all influence how much income different hours generate.

Compensation Models: Why Productivity Matters

Physician income is heavily shaped by the compensation structure in their employment contract. Common models include:

1. Fee‑for‑Service and RVU-Based Compensation

In these models, physicians are paid per service or based on relative value units (RVUs):

- More patients seen or procedures performed = more RVUs = higher compensation

- Encourages longer clinical hours, double‑booking, and high patient throughput

- Common in many specialties, particularly procedural fields and outpatient practices

Physicians in these systems may choose to:

- Work longer weeks or more clinic sessions to increase income

- Focus on more lucrative procedures or higher‑acuity care

- Optimize scheduling to minimize gaps and no‑shows

2. Salary with Productivity or Quality Bonuses

Many hospital‑employed physicians receive:

- A base salary

- Plus bonuses for:

- Meeting RVU targets

- Hitting quality or patient‑satisfaction metrics

- Taking additional call or leadership roles

Longer hours may increase bonus eligibility, but income is somewhat buffered from short‑term fluctuations in volume.

3. Pure Salary or Time-Based Models

More common in academics, certain government or VA systems, and some unionized settings:

- Compensation may be relatively fixed regardless of hours or RVUs

- Physicians may still work long hours due to:

- Academic expectations

- Coverage needs

- Institutional culture

In these roles, physicians may accept more modest physician salary growth in exchange for stability, benefits, and academic or mission‑driven work.

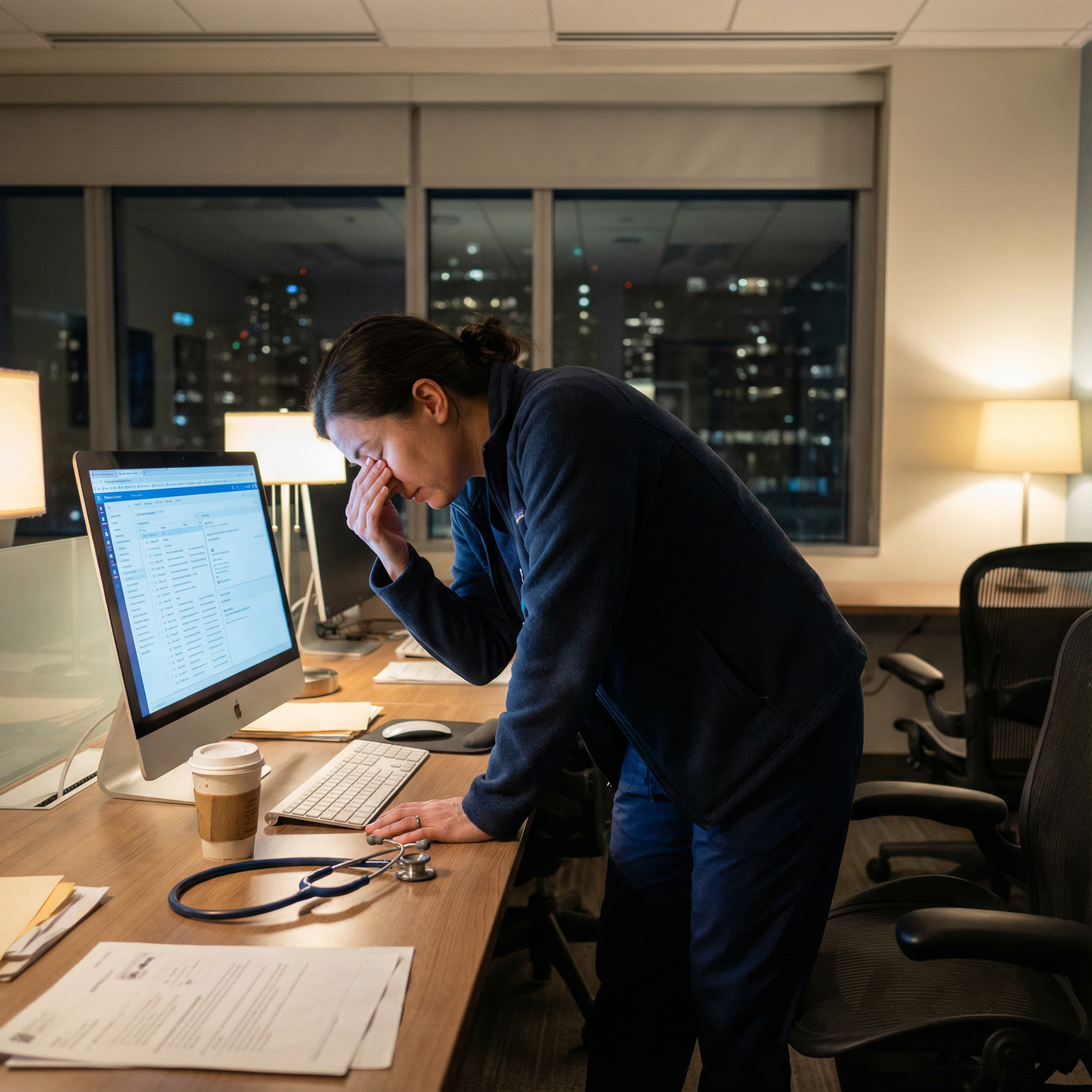

Burnout, Well‑Being, and the Hidden Costs of Long Work Hours

Physician burnout has become a central topic in healthcare insights and workforce planning. Long physician work hours are a major contributor—but not the sole cause.

How Burnout Develops

Burnout typically involves a combination of:

- Emotional exhaustion

- Depersonalization or cynicism toward patients

- Reduced sense of personal accomplishment

Drivers include:

- Excessive workload and long, irregular hours

- Administrative burden and EHR documentation

- Lack of autonomy and limited control over schedule

- Moral distress from systemic constraints (e.g., insurance barriers, resource limitations)

Certain specialties with intense work hours and high emotional stakes—such as emergency medicine, critical care, and some surgical fields—have historically reported higher burnout rates.

Financial and Career Consequences of Burnout

Burnout doesn’t just affect quality of life; it has clear financial implications:

Reduced clinical hours:

- Many physicians scale back on call, nights, or total FTE (e.g., from 1.0 to 0.8) to preserve mental health.

- This directly reduces income, even if hourly rates remain high.

Early retirement or career change:

- Burnout is a major driver of physicians leaving clinical practice, switching specialties, or moving into nonclinical roles (e.g., administration, industry, consulting).

- This can dramatically cut lifetime earning potential, even if it improves well‑being.

Decreased productivity:

- Burned‑out clinicians may see fewer patients, avoid complex cases, or decline leadership roles, all of which can lower compensation in productivity‑based models.

From a systems perspective, burnout increases turnover, recruitment costs, and malpractice risk, which ultimately affects the broader healthcare economy.

Strategies to Balance Workload, Salary, and Well‑Being

For residents and early‑career physicians, it’s critical to think intentionally about how physician work hours will fit into long‑term life goals.

1. Choose Specialty and Practice Type with Eyes Wide Open

When selecting a specialty, consider not just passion and prestige, but:

- Typical weekly hours and call burden

- Schedule predictability (e.g., shift work vs. office hours vs. OR days)

- Income‑to‑hours ratio and long‑term earning potential

- Flexibility options (part‑time, job‑sharing, telemedicine, locum tenens)

Example:

- An orthopedic surgeon may earn far more than a pediatrician but at the cost of longer and more physically demanding hours and heavier call.

- A dermatologist may accept a competitive but not top‑tier salary for more predictable hours, outpatient-only practice, and minimal emergencies.

2. Negotiate Smartly When Reviewing Job Offers

Physicians often focus on base salary and signing bonuses, but schedule terms can be equally important:

- Clarify expected weekly hours and what is considered “full time”

- Ask about:

- Average daily patient volume

- Number of clinic sessions per week

- Time allocated for documentation, meetings, and administrative tasks

- Call frequency, type (in‑house vs home), and compensation for extra call

- Explore part‑time or flexible options, even if you don’t plan to use them immediately

Negotiating additional support (scribes, nurse practitioners/physician associates, MA staffing, robust EHR templates) can reduce after‑hours charting and protect evenings and weekends.

3. Use Efficiency Tools to Protect Your Time

Improving efficiency can help you maintain or increase income without endless hours:

- Develop standardized note templates and order sets

- Batch tasks (e.g., lab review, inbox messages) at dedicated times

- Learn to say no to low‑value meetings or commitments that don’t align with your goals

- Use team-based care models effectively—delegate appropriately to nurses, MAs, and advanced practice clinicians

Over a career, even small gains in daily efficiency (e.g., 30–60 minutes saved) compound into hundreds of hours regained annually.

4. Prioritize Sustainable Workload Early

Early in their careers, many physicians feel pressure to maximize income to quickly pay down loans or “prove themselves” in a new group. While understandable, chronically overextending can backfire.

Consider:

- Setting a maximum sustainable weekly hour range (e.g., 50–55 hours) and designing your practice around it

- Paying aggressive amounts toward loans while still establishing boundaries to avoid burnout

- Planning periodic “reset” periods—vacations, academic time, or reduced call stretches

Ultimately, balancing physician work hours, physician salary, and personal life is not a one‑time decision but an ongoing process of adjustment.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is the average number of hours physicians work per week?

Most physicians work around 50–55 hours per week on average, though this varies substantially by specialty, practice setting, and career stage. Primary care and many outpatient specialists often work 45–60 hours, while surgeons, hospitalists, and some acute care specialists may regularly exceed 60 hours, especially when on call.

2. Do physicians who work more hours always earn higher salaries?

In general, more clinical hours and higher patient or procedure volumes are associated with higher physician salary, especially in fee‑for‑service or RVU‑based models. However:

- Some high-paying specialties (e.g., orthopedic surgery) have intensive hours and high compensation.

- Other specialties (e.g., dermatology, some radiology jobs) offer strong incomes with moderate hours.

- Productivity, payer mix, and practice efficiency can be as important as raw hours in determining earnings.

3. Which medical specialties have the most demanding work hours?

Specialties commonly associated with heavier time demands and intense schedules include:

- General surgery and many surgical subspecialties

- Obstetrics and gynecology (especially with obstetric call)

- Some interventional fields (e.g., interventional cardiology)

- Certain acute care roles like trauma surgery and critical care

Emergency medicine also involves demanding work, though total scheduled hours may be more capped; the challenge is often shift timing, night work, and psychological load rather than pure volume alone.

4. How does burnout affect a physician’s income and career?

Burnout can:

- Prompt physicians to reduce hours, decline extra call, or cut back on procedures—directly lowering income

- Lead to early retirement, leaving clinical practice, or changing careers, which significantly decreases lifetime earnings

- Reduce productivity, affect patient volumes, and limit willingness to take on leadership or administrative roles that might increase compensation

Addressing burnout early and proactively can help protect both long‑term health and financial stability.

5. What can medical students and residents do now to prepare for a sustainable career?

You can start laying the groundwork by:

- Observing physician work hours and lifestyles across specialties during rotations

- Asking attendings honest questions about call, documentation burden, and burnout

- Learning basic financial literacy (loan management, budgeting, contract fundamentals) so you don’t feel compelled to overwork indefinitely

- Practicing time management, boundary‑setting, and self‑care skills during training

- Prioritizing programs and jobs that respect work‑life balance and provide institutional support for physician well‑being

Understanding how physician work hours intersect with salary, burnout, and long‑term career satisfaction will help you make informed decisions—so you can build a medical career that is not only financially viable, but also personally sustainable and fulfilling.