What do you actually say when they ask, “Tell me about a challenge you’ve faced,” and your real challenge is trauma, illness, or burnout?

You’re not alone in that dilemma. A lot of applicants have serious stuff in their history—death of a parent, depression, eating disorders, abusive relationships, immigration trauma, financial collapse, major medical diagnoses. And they’re torn between two bad options:

- Overshare and feel exposed (or worry they’ll silently red-flag you).

- Keep it all surface-level and sound fake, robotic, or “too perfect.”

Let’s fix that.

I’ll walk you, step by step, through how to talk about real hardship in residency interviews without turning the room into a therapy session, losing control of your emotions, or raising unnecessary concerns about your reliability or stability.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Family Illness/Death | 40 |

| Mental Health | 30 |

| Financial/Work | 35 |

| Immigration/Displacement | 20 |

| Personal Illness | 25 |

| Abusive Environment | 15 |

First: Decide if this hardship belongs in the room at all

Not every hardship needs to be shared. Some absolutely should not be.

Ask yourself three questions:

- Did this hardship meaningfully shape who I am as a future physician or how I show up clinically?

- Can I talk about it without breaking down, going numb, or dissociating?

- Will a reasonable program director hear this and think, “That explains growth,” rather than, “Is this going to be a future problem?”

If you cannot honestly answer yes to all three, it probably doesn’t belong in your interview.

Some examples.

Good candidates for interview-appropriate hardships:

- You worked two jobs in undergrad to support family and it shaped your work ethic and empathy for low-income patients.

- You failed a course or had a leave of absence and actually rebuilt your study systems, got help, and performed consistently better.

- You had a serious medical issue that’s now well-controlled and it changed how you understand chronic illness and the health system.

- You struggled with anxiety, got treatment, and now have stable functioning and a realistic sense of limits.

Risky or usually-bad topics to lead with:

- Ongoing, unresolved legal situations.

- Fresh, raw trauma where you still cry when you mention it.

- Detailed descriptions of abuse, violence, self-harm, or suicidal behavior.

- Uncontrolled substance use, current addiction, or chaotic behavior you haven’t clearly and convincingly addressed.

You’re not obligated to confess your whole life to strangers to be “authentic.” Authenticity is telling the truth at an appropriate depth, not sharing your entire chart.

If your gut already says, “I’m not ready to talk about this without losing it,” listen to that.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Consider Hardship |

| Step 2 | Do not use in interview |

| Step 3 | Maybe skip or use lightly |

| Step 4 | Use in a controlled, structured way |

| Step 5 | Shaped you as a physician? |

| Step 6 | Can you discuss without distress? |

| Step 7 | Stable/resolved enough? |

| Step 8 | Explains growth or change? |

Second: Pick the right level of detail

The biggest mistake people make is confusing “honesty” with “full disclosure.”

- A basic understanding of what happened.

- Reassurance about your current functioning and reliability.

- Evidence that you learned, adapted, or grew.

Programs do not need:

- Graphic detail.

- Every family member’s psychiatric diagnosis.

- Every relapse, every fight, every meltdown.

- A play-by-play of your worst weeks.

Think in three layers of detail:

- Headline level: “My father passed away unexpectedly during M3.”

- Context level: “I flew home frequently and took on some caregiving and financial responsibilities, which affected my academic performance that semester.”

- Unnecessary depth (don’t go here): “He died by suicide; I found him; there were police and court issues…” — that’s for your therapist, not your PD.

When in doubt: stay at headline + light context. If they ask for more, add a bit. But always keep it clinical, brief, and controlled.

Example before/after:

Too much:

My ex was emotionally abusive and very controlling. I developed severe depression, had panic attacks before exams, and at one point I wasn’t even sure I wanted to live. I isolated a lot and stopped going to class.

Controlled:

During my second year, I was in a very unhealthy relationship that significantly affected my mental health and concentration. I underperformed academically that year and needed to re-evaluate my support systems and coping strategies.

See the difference? Same truth. Less exposure. Less risk of the room going quiet and awkward for 30 seconds.

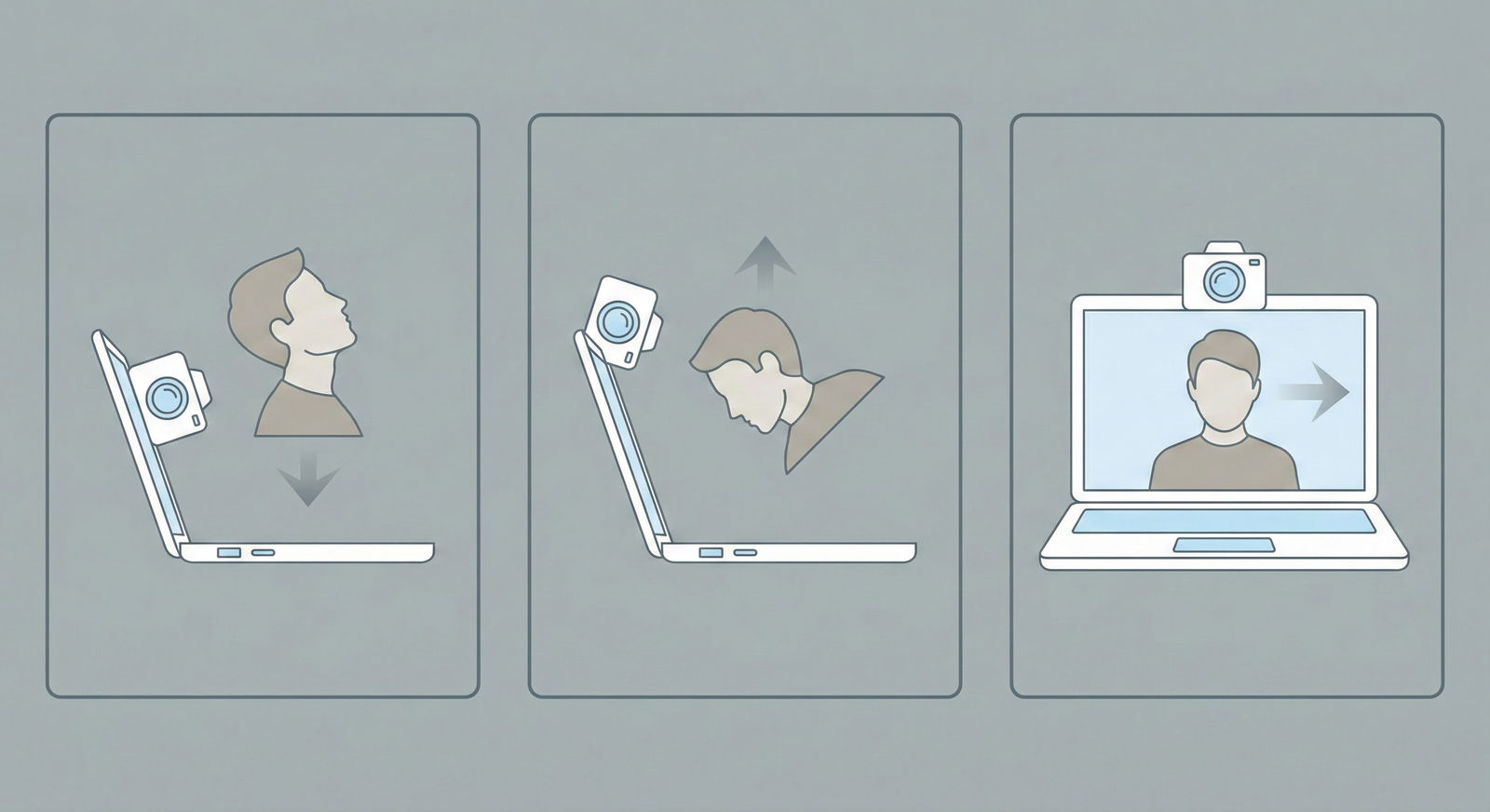

Third: Use a rigid structure so you don’t ramble or overshare

If you go in “planning to just be honest,” you’ll overshare. Because nerves + silence + slightly empathetic nods from interviewers = talking too much.

Use this 4-part spine. Always.

- One-line headline – What happened, in neutral language.

- Impact – Briefly, what was at risk or what was hard.

- Response – What you did to handle it (actions, not feelings).

- Growth/Now – What you learned and what your current functioning looks like.

Example: parental illness during clerkships

Headline:

“During my third-year clerkships, my mother was diagnosed with metastatic cancer.”Impact:

“I was flying home on weekends, helping coordinate her appointments, and it affected my focus and my shelf exam performance, especially early in the year.”Response:

“I met with our dean, adjusted my schedule to cluster certain rotations, worked with a therapist to manage anxiety, and developed a very structured weekly study plan so I could still perform clinically while being present for my family.”Growth/Now:

“That period forced me to learn realistic time management, to ask for help early, and to set boundaries with myself. My evaluations improved steadily, I passed all my clerkships, and in the last year I’ve maintained stable performance while still being involved in my family’s care.”

That’s honest. Human. Also composed, functional, and reassuring.

Your goal: by the end, the interviewer is thinking, “They’ve been through something hard and came out more resilient, not more fragile.”

Fourth: Choose your words like a clinician, not a confessional writer

Language matters. Certain phrases make programs nervous, even if you’re technically fine now.

Better: controlled, clinical, past-focused wording.

Problematic: ongoing, chaotic, unresolved wording.

Let’s do some translations.

| Risky Phrase | Safer Alternative |

|---|---|

| “I had a mental breakdown.” | “I experienced a significant episode of depression/anxiety.” |

| “I was suicidal.” | “I had serious thoughts of self-harm and received urgent psychiatric treatment.” |

| “I flamed out and couldn’t handle anything.” | “My coping mechanisms were overwhelmed and my functioning declined.” |

| “My substance use got out of control.” | “I developed unhealthy coping with alcohol and entered treatment, and I’ve maintained sobriety since [date].” |

| “My family is extremely toxic and dysfunctional.” | “I come from a very challenging family environment with limited support.” |

You’re not lying. You’re taking raw content and translating it into professional language—exactly what you’ll have to do when you present complicated social histories on rounds.

If you are talking about mental health or substance use, you must include:

- Clear indication that it’s past or well-controlled.

- Evidence of treatment (therapy, medication, program).

- A time frame that shows stability (e.g., “For the last two years…”).

- Concrete proof of reliable functioning since (boards, rotations, research, consistent work record).

If you can’t show that stability yet, be very cautious about centering that hardship in your interview narrative.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Brief Context | 20 |

| Impact | 20 |

| Concrete Actions | 30 |

| Current Stability/Growth | 30 |

Fifth: Match depth to the type of question

Not every “challenge” question deserves your deepest trauma. In fact, most don’t.

Common traps:

Q: “Tell me about a time you had a conflict on a team.”

A: Launching into your parents’ divorce and how you became the family mediator.

Wrong scale.Q: “What’s the biggest challenge you’ve overcome?”

A: Story about failing a quiz in undergrad.

Too trivial. They know you’re hiding something real.

Rough guidelines:

Use smaller-scale hardships for:

- Team conflict.

- Difficult feedback.

- Time you made a mistake.

- Handling stress on a particular rotation.

Use larger-scale hardships for:

- Biggest challenge you’ve faced.

- Tell me about a formative experience.

- Your personal statement-related follow-ups.

- Explanation of red flags (LOA, failed step, failed course).

If you’ve got a major hardship that also explains a “red flag” (failed Step, LOA, course remediation), that’s often the right place to use it—but in a tightly structured way.

Example: explaining a failed Step 1 attempt linked to depression

You do not say:

I was deeply depressed, barely able to get out of bed, and my life was falling apart.

You say:

“During my initial Step 1 preparation, I was dealing with untreated depression that significantly affected my concentration and energy. I underestimated how impaired I was and sat for the exam before I was ready, and I failed. After that, I took a formal leave, started regular therapy and medication management, and worked with student affairs to create a realistic study schedule. I returned, passed on the second attempt with a solid score, and since then I’ve completed all clinical rotations on time with strong evaluations. That experience taught me to recognize when I’m not okay and to address it proactively rather than just trying to push through.”

Same truth. Different level of control.

Sixth: Control your emotions ahead of time (so you don’t crack on game day)

If you can’t get through your hardship story without tearing up, long pause, or voice shaking, you are not ready to tell that version.

Interviewers are human. Some will be incredibly kind. Others will be quietly thinking, “How’s this person going to handle a bad night in the ICU?”

Here’s what to do before interview day:

Write out your hardship story using the 4-part structure. Then cut it down by 30%. That’s closer to what you’ll actually have time for.

Say it out loud to yourself — in the car, in your room, whatever. Notice the parts where your throat tightens. Edit those lines to be more neutral. Example:

- Too raw: “It was the worst period of my life.”

- Swap: “It was an extremely challenging period.”

Practice with one or two trusted people (classmate, advisor, therapist). Ask them:

- Did anything feel too personal or graphic?

- Would this make you worry about my stability?

- Where did I ramble?

Set a time limit: Most answers should be 60–90 seconds. Practice with a timer. If you’re over 2 minutes, you’re oversharing or overexplaining.

If you still choke up every single time, scale the story back. Use a lighter version or a different challenge. Your mental health matters more than impressing a PD with your vulnerability.

Seventh: Know your hard boundaries in the room

You’re allowed to have lines you won’t cross. Program directors don’t own your trauma history.

Sometimes, you’ll get an interviewer who likes to “dig.” You answer at a reasonable level, and they push:

- “Can you tell me more about what exactly happened?”

- “What do you mean by ‘unhealthy relationship’?”

- “How severe was your depression?”

You don’t have to go further than you’re comfortable. You just have to maintain professionalism while holding the line.

Scripts you can steal:

- “I’m happy to share at a high level, but I’d prefer not to go into more detail than I’ve already described. The key impact on my training was…”

- “The specifics are quite personal, so I’ll keep it general, but the important takeaway for my development as a resident is…”

- “I appreciate the question. The most relevant part for residency is that I’m now stable, in care as appropriate, and have maintained consistent performance for the last [X] years.”

You redirect back to functioning, growth, and relevance.

If someone is truly out of line (rare but not impossible), you can be firmer:

- “I’m not comfortable going into more detail about that aspect of my history, but I’m glad to answer questions about how I function now as a trainee.”

That’s not being difficult. That’s setting normal professional boundaries.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| What Happened | 15 |

| Impact on You/Training | 20 |

| What You Did | 25 |

| What You Learned/Now | 30 |

Eighth: If your hardship is ongoing, you must be extra careful

Some of you are still in the middle of it:

- Parent currently terminally ill.

- Ongoing custody/immigration/legal battles.

- Chronic mental health condition that’s real work to manage.

- Financial strain that’s not going anywhere.

You don’t have to pretend everything is perfect. But you do have to show:

- You can still function consistently.

- You have systems and supports in place.

- You’ve thought realistically about residency demands.

Example: ongoing chronic illness

Bad:

“I’m still struggling a lot with my autoimmune disease. Some days I can barely get out of bed, but I push through.”

Better:

“I was diagnosed with an autoimmune condition during M2, which required significant treatment adjustments. With my rheumatologist, we’ve found a regimen that has kept me stable for the last 18 months. I have occasional flares, but they’re predictable enough that I’ve been able to complete all clinical rotations without absences and meet my responsibilities reliably. This experience has made me extremely intentional about sleep, time management, and early communication if something starts to slip.”

Programs aren’t looking for perfect health. They’re looking for predictability and self-awareness.

If you’re not sure how your situation will be perceived, talk to a dean or mentor who has actually sat on selection committees. They will be blunter with you than the internet.

Ninth: Don’t let your hardship become your entire personality in the interview

Having a big story can become a trap. Once you see how compelling it is, you start using it everywhere:

- Why this specialty? Insert hardship.

- Tell me about a time you failed. Insert hardship.

- What are your strengths? Somehow, still hardship.

By the end, you’ve branded yourself as “the grief applicant” or “the addiction applicant” instead of a multifaceted human who also loves cardiology, teaches med students, and codes on the side.

Use the hardship where it’s naturally relevant:

- Biggest challenge.

- Red flag explanations.

- Questions about resilience, growth, or adversity.

And then, deliberately answer some questions with zero reference to your painful history:

- Talk about a clinical mistake and what you changed.

- Describe a communication challenge with a nurse or attending.

- Share a research setback and how you adapted.

You want the committee to walk away thinking:

- “They’ve been through some serious things.”

- “They’re more mature and grounded because of it.”

- “Also, they’re clearly a good team fit, clinically solid, and actually excited about this specialty.”

If they only remember your tragedy, that’s a problem.

Tenth: Quick reality check on what programs actually think

Here’s the unvarnished truth from what I’ve seen and heard behind closed doors:

Programs generally react well when:

- The hardship clearly explains a dip in your record or a pivot.

- You speak about it calmly, concisely, and without drama.

- You emphasize treatment, support, and long-term stability.

- Your recent performance backs up your story.

Programs get uneasy when:

- The story is raw, chaotic, or overshared.

- You emphasize suffering more than actions.

- You have no clear support systems or ongoing care.

- You seem overly attached to the identity of “overcomer of hardship” and under-attached to “future reliable colleague.”

Your job is to reduce uncertainty. Not to win a trauma Olympics.

If you remember nothing else, keep these three points:

- Structure is your shield: Headline → Impact → What you did → Growth/Now. Use it every time. It keeps you from rambling and oversharing.

- Professional language + clear stability: Be honest, but translate your story into clinical, past-focused terms and show concrete, recent evidence that you function reliably.

- Your hardship is a chapter, not the book: Use it where it fits, then let the rest of the interview show who you are as a future resident, colleague, and physician—not just what you survived.