Understanding the Fellowship Landscape as a Non‑US Citizen IMG

Preparing for fellowship as a non-US citizen IMG is not just about being a good clinician. It is about understanding a complex intersection of training requirements, immigration rules, institutional preferences, and timing. When you start early and plan intentionally, you dramatically increase your chances of matching into a strong program.

As a foreign national medical graduate, you face three additional layers of planning beyond what US graduates usually think about:

- Visa and immigration planning

- Timing your exams, milestones, and research

- Targeting programs that realistically sponsor or accept your status

This article walks you through fellowship preparation step-by-step, from early residency to application season, with a focus on what is unique for a non-US citizen IMG. We will also highlight practical “to‑do” lists and timeline checkpoints.

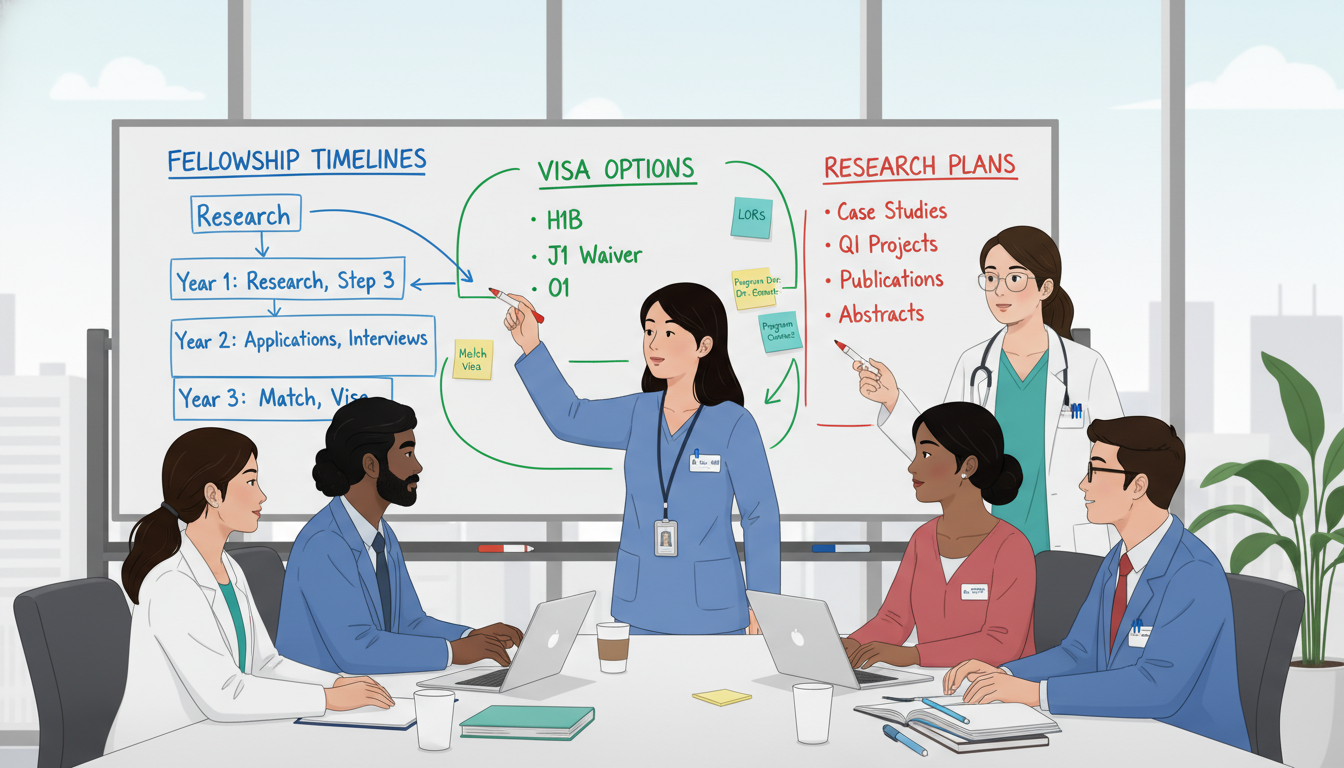

Mapping Your Fellowship Application Timeline

Understanding the fellowship application timeline is critical to avoid last-minute stress and missed opportunities. Below is a general framework for internal medicine subspecialties (Cardiology, GI, Pulm/CC, Heme/Onc, etc.) using ERAS and NRMP. Other specialties (e.g., anesthesia, radiology, surgery subspecialties) follow similar principles but may vary in dates and match systems.

Global Overview

- Residency PGY‑1: Explore interests, build foundations, start networking.

- Residency PGY‑2: Solidify specialty choice, intensify research, identify mentors, start exam planning if needed (e.g., USMLE Step 3 if not done).

- Residency PGY‑2 late – PGY‑3 early: Application year – letters, personal statement, ERAS, interview season.

- Post‑match: Visa planning, contract review, on-boarding.

Month‑by‑Month Approximate Timeline (Internal Medicine Example)

PGY‑1 (Year 1 of Residency)

July–December

- Learn how fellowship works in your field: talk to fellows, attend fellowship Q&A sessions, read society websites (ACC for cardiology, ASCO for oncology, etc.).

- Track your board scores, evaluations, and procedure logs carefully.

- Decide if you might need to take USMLE Step 3 early (important for some visa pathways and competitiveness).

January–June

- Start one or two small research projects (case report, QI project) to get your name on presentations or abstracts.

- Build relationships with potential future letter writers—attendings in your desired subspecialty.

- For highly competitive fellowships (cards, GI, heme/onc), start reading core literature and guidelines.

PGY‑2 (Year 2 of Residency)

July–December

- Clarify your target fellowship (e.g., “Academic Hematology/Oncology with interest in malignant hematology.”)

- Aim to submit at least one abstract to a national meeting (e.g., AHA, CHEST, ASH, ATS, ACG).

- If not done, schedule USMLE Step 3 early enough that the score will be available on applications; step 3 is especially important for H‑1B possibilities.

- Identify 3–4 strong potential mentors and letter writers.

January–March (Application preparation peak)

- Draft your CV and keep it continuously updated.

- Start writing your personal statement; revise repeatedly with input from mentors.

- Prepare a list of programs to apply to, filtering for those that:

- Accept non-US citizen IMG applicants

- Sponsor J‑1 and/or H‑1B if relevant

- Update your program list with real information (e.g., call coordinators or check websites).

April–June

- ERAS opens; begin entering your information and experiences.

- Confirm letters of recommendation (LoRs) – politely remind letter writers, provide CV, personal statement draft, and a summary of your work together.

- Finalize your application materials by the time programs start downloading applications (usually July).

PGY‑3 (Year 3 of Residency) – Application and Interview Season

July–August

- Submit ERAS application during the earliest reasonable window.

- Respond promptly to any supplemental questions or application requests from programs.

- Practice mock interviews with attendings or faculty.

September–November

- Interview season for many specialties.

- Keep clinical performance strong; PDs may be asked informally about your current work.

- Send thank‑you emails to interviewers and periodic interest updates to top programs.

December–February

- Rank lists are submitted (if using NRMP or specialty-specific match).

- Continue research and clinical work; don’t let performance drop.

- Begin thinking about visa strategy for fellowship (J‑1 vs H‑1B vs O‑1), especially if you are changing status.

March–June (Post‑match)

- If matched: work through credentialing, state licensing, and visa paperwork.

- If unmatched: decide whether to re‑apply, do a research year, or pursue a different path.

Understanding the fellowship application timeline early in residency helps you structure your milestones, especially research and exam timing. For a non-US citizen IMG, a late Step 3 or a missing publication can be the difference between an interview and a silent rejection.

Strategic CV Building: Clinical, Academic, and Leadership Pillars

Your fellowship application is ultimately a story told through your CV, personal statement, letters, and interviews. Programs want to see a coherent trajectory that shows you are ready for subspecialty training and likely to succeed in US academic or community environments.

1. Clinical Excellence: The Non‑Negotiable Foundation

Regardless of your background as a non-US citizen IMG, your first priority is to be an outstanding resident.

Focus areas:

- Strong evaluations: Aim for consistent “exceeds expectations” or equivalent in core rotations, especially in your target subspecialty.

- Procedural competence (when relevant): Document logs (central lines, bronchoscopies, endoscopies, etc.) and reflect on progress.

- Professionalism and teamwork: Program directors worry about visas and paperwork; they will only go the extra mile if you are clearly someone worth the effort.

Actionable tips:

- Ask for mid‑rotation feedback and implement suggestions quickly.

- Volunteer for complex cases in your subspecialty; this shows enthusiasm and builds your clinical narrative.

- Learn the US practice style—closed-loop communication, concise sign‑outs, evidence-based presentations.

2. Research and Scholarly Activity: Building Credibility

For many non-US citizen IMGs, research is the key differentiator that answers the question: “Why should a fellowship invest in this candidate who needs visa sponsorship?”

You do not need a PhD or 20 publications. You need evidence of curiosity, productivity, and follow‑through.

Tiered goals:

- Minimum: 1–2 case reports or case series + 1 QI project.

- Competitive (for popular subspecialties): A mix of:

- Abstracts at regional/national conferences

- At least 1–2 peer‑reviewed publications (even as middle author)

- Participation in ongoing clinical or outcomes research projects

Where to start:

- Join or start a quality improvement project on your ward (e.g., sepsis bundle compliance, glycemic control).

- Approach subspecialty faculty with a specific ask, e.g.,

“I am interested in heart failure and would love to help with data collection or chart review on any projects your group is working on.” - Attend journal club and volunteer to critically appraise articles.

Pitfalls to avoid:

- Taking on too many projects and finishing none.

- Projects with no clear endpoint or mentorship.

- Predatory journals and paid publications that may harm credibility.

3. Teaching, Leadership, and Service: Showing You Are a Future Faculty Member

Fellowship programs look for people who can:

- Teach residents and medical students

- Represent the program professionally

- Potentially join faculty down the road

Concrete roles to seek:

- Chief resident (if timing allows for a post‑residency gap year)

- Resident teaching award or formal teaching roles (e.g., simulation facilitator, OSCE examiner)

- Committee membership: GME committee, QI committee, DEI initiatives

- Organizing journal clubs, board review sessions, or resident conferences

For non-US citizen IMGs, leadership roles show that you are integrated into the US system and trusted by local faculty, which can counter implicit bias about overseas training.

4. Tailoring Your CV for Fellowship

Your CV should highlight:

- Your fellowship-relevant identity (“Future interventional cardiologist with outcomes research focus in structural heart disease” rather than “generic internal medicine resident”).

- A clear structure:

- Education and Training

- Certification and Licensure

- Clinical Experience

- Research and Publications

- Presentations and Posters

- Leadership and Teaching

- Awards and Honors

- Professional Memberships

For every activity, quantify impact when possible (e.g., “Reduced door‑to‑needle time for stroke by 18% over 12 months.”).

Navigating Visa, Sponsorship, and Eligibility Realities

This is where preparing for fellowship as a non-US citizen IMG becomes uniquely complex.

Common Visa Pathways in Fellowship

J‑1 Exchange Visitor Visa

- Most common for fellowship.

- Sponsored by ECFMG, not by the program directly (though the program must support it).

- Requires a two‑year home-country physical presence afterward unless you obtain a waiver.

Pros:

- Widely accepted by fellowship programs.

- Often simpler administratively for institutions.

Cons:

- Post‑fellowship options may be limited without a J‑1 waiver or change of status.

- Less flexibility for moonlighting in many cases.

H‑1B Specialty Occupation Visa

- Employer-sponsored work visa.

- Some fellowships (not all) are willing to sponsor H‑1B.

Key points:

- Typically requires passing USMLE Step 3 before sponsorship.

- Subject to cap-exempt vs. cap-subject considerations depending on sponsoring institution.

- Provides more flexibility for subsequent employment and green card processing.

O‑1 (Individuals with Extraordinary Ability)

- Less common but relevant for highly accomplished researchers.

- Requires a strong portfolio of publications, citations, awards, and international recognition.

How to Research Program Visa Policies

- Check each program’s website:

- Look specifically for “Eligibility & Visa Status” or “International Medical Graduates” sections.

- Email or call program coordinators with a concise question such as:

- “Could you please confirm whether your fellowship program sponsors J‑1 and/or H‑1B visas for foreign national medical graduates?”

- Use this information to stratify your application list:

- Tier 1: Programs that explicitly sponsor your needed visa type.

- Tier 2: Programs that sponsor J‑1 only, but not H‑1B.

- Tier 3: Programs with unclear or restrictive policies.

Combining Fellowship Plans With Long‑Term Immigration Strategy

Ask yourself early: “Where do I realistically want to be 5–10 years from now?”

- If you plan to return to your home country, J‑1 may be perfectly acceptable or even ideal.

- If you hope to stay in the US long-term, consider:

- Whether you will be comfortable seeking a J‑1 waiver job after fellowship.

- The feasibility of transitioning from J‑1 to H‑1B via waiver positions.

- Whether your profile might support an O‑1 or NIW (National Interest Waiver) later.

When deciding how to get fellowship opportunities that align with your immigration goals, combine:

- Short-term competitiveness (what will help me match now?)

- Long-term viability (will this visa path block or delay my goals later?)

Never make immigration decisions in isolation—discuss them with:

- Your institution’s GME office or visa/immigration desk

- Experienced attendings who were once non-US citizen IMGs

- When possible, an immigration attorney familiar with physician visas

Application Components: How to Make Each Piece Work for You

Understanding how to get fellowship interviews and offers as a foreign national medical graduate means optimizing each application component strategically.

Personal Statement: Tell a Focused, Credible Story

Goals of your personal statement:

- Explain why this subspecialty, not just “I like cardiology.”

- Show how your past experiences (including international training) led to your current focus.

- Demonstrate understanding of the US training environment.

- Convey that you are reliable, curious, and a good colleague.

Structure suggestion:

- Hook: A specific clinical or research experience that shaped your interest.

- Trajectory: How your path from medical school (including being a non-US citizen IMG) to residency has prepared you.

- Current identity: What you bring now—skills, research interests, teaching experiences.

- Future goals: Academic vs. community, clinical niche, research focus.

- Fit: The kind of fellowship environment you are seeking (without naming specific programs in the generic statement).

Avoid:

- Generic, cliché stories that could apply to anyone.

- Overemphasis on hardship without tying it to strengths and resilience.

- Bringing up visa issues directly; that is handled elsewhere.

Letters of Recommendation: Your Most Powerful Asset

For non-US citizen IMGs, strong US-based letters often outweigh everything else.

Aim for:

- 3–4 letters, at least 2–3 from US subspecialists in your target field.

- At least one letter from your program director or core residency leadership.

Choose letter writers who can:

- Comment on your clinical excellence.

- Describe your work ethic and teamwork.

- Highlight your research or scholarly contributions if relevant.

- Provide concrete examples, not just adjectives.

Tactics:

- Ask early: “Would you be comfortable writing a strong letter of recommendation on my behalf for fellowship?”

- Provide:

- Your CV

- Personal statement draft

- A brief summary of key cases, projects, or interactions you had with that attending

Do not:

- Use letters from your home country unless they are exceptionally strong and relevant, and even then only as a supplemental letter, not a core one.

- Ask for letters from attendings who barely know you.

ERAS Application and Program Signaling (if applicable)

Fill ERAS thoughtfully:

- Use bullet points with active verbs and quantifiable impact.

- Classify research and presentations accurately.

- Clearly mark international vs. US experiences without hiding them.

Program signaling (where available):

- Use signals strategically for:

- Programs that sponsor your visa type.

- Programs with strong alignment to your research or niche interests.

- Places where you have some connection or regional preference.

Interview Preparation: Addressing IMG and Visa Issues Smoothly

During interviews, you will often face questions related to:

- Your status as an international medical graduate

- Transition from non‑US system to US training

- Long‑term goals and visa implications (occasionally and indirectly)

Prepare concise, confident responses:

- On being an IMG:

- “My training in [Country] exposed me to [specific strengths], and my US residency has helped me adapt those skills to this healthcare system. I now feel very comfortable practicing within US guidelines and multidisciplinary teams.”

- On long‑term goals:

- “My long‑term goal is to work in [academic/community] practice in the US with a focus on [niche area]. I understand the visa and waiver landscape and am prepared to be flexible within that framework.”

Practice:

- Mock interviews with faculty, especially those who are previous non‑US citizen IMGs.

- Common clinical and ethical scenarios in your subspecialty.

- “Tell me about yourself” and “Why this specialty?” questions.

Coping With Extra Challenges and Building Support Systems

As a non-US citizen IMG preparing for fellowship, you are often doing more work than your peers just to have the same shot:

- Adapting to a new healthcare system

- Navigating visa uncertainty

- Sometimes dealing with accent bias or assumptions about your training

Build a Mentorship Network

You need more than one mentor:

- Career mentor: Helps you choose specialty, plan long-term path.

- Research mentor: Guides your scholarly output.

- Peer mentor: Someone 1–2 years ahead of you (e.g., current fellow).

- Cultural/transition mentor: Another IMG who understands the non‑academic challenges.

Where to find them:

- Your residency program’s faculty mentoring structure.

- Alumni networks, particularly those who are non-US citizen IMGs now in fellowships.

- National societies’ mentorship programs (AHA, ATS, ASCO, etc.).

Managing Stress, Burnout, and Setbacks

Common challenges:

- Failing to match on first try

- Visa changes or delays

- Feeling isolated, especially if far from family

Practical coping strategies:

- Have a Plan B before application season:

- Research year

- Chief year

- Hospitalist role with continued research

- Take scheduled breaks. Burnout will compromise performance and applications.

- Use institutional resources:

- Counseling and wellness programs

- GME support services

- Join communities of other non-US citizen IMGs (online and in-person).

If You Don’t Match the First Time

Being unmatched as a foreign national medical graduate does not end your journey.

Steps:

Get honest feedback from mentors and program leadership:

- Was it visa restrictions?

- CV strength?

- Interview performance?

- Overly competitive target list?

Decide on a gap strategy:

- Research fellowship/academic position in your specialty of interest.

- Hospitalist job with continued research and leadership involvement.

- Chief residency if offered.

Strengthen weaknesses:

- Publish ongoing projects.

- Improve US-based references.

- Consider additional certifications (e.g., ultrasound, specific courses).

Re‑apply with a clear narrative:

- “In the past year I have deepened my experience in [field], completed X publications, and confirmed my commitment to [subspecialty].”

FAQs: Fellowship Preparation for Non‑US Citizen IMGs

1. When should I start preparing for fellowship as a non-US citizen IMG?

You should start thinking about fellowship in PGY‑1, especially if you are aiming for competitive fields. This does not mean committing on day one, but:

- By the end of PGY‑1, you should have:

- Some idea of preferred subspecialties.

- At least one research or QI project started.

- By early PGY‑2, you should:

- Firm up your target fellowship.

- Engage in more focused research and mentorship.

- Plan for USMLE Step 3 if an H‑1B is a possibility.

Starting early gives you time to align your clinical, research, and visa strategies with the fellowship application timeline.

2. Is it harder for non-US citizen IMGs to get fellowship in competitive specialties?

Yes, it can be harder, largely due to:

- Visa limitations (some programs only take US citizens or permanent residents).

- Perceived risk or administrative burden from the program’s perspective.

- Intense competition from US graduates and permanent residents.

However, non-US citizen IMGs match every year into cardiology, GI, heme/onc, pulm/CC, and other competitive fields. The key is:

- Building a strong, targeted CV (research, letters, clinical excellence).

- Applying widely, prioritizing programs that historically support foreign national medical graduates.

- Presenting a coherent career story and demonstrating added value (e.g., language skills, unique research expertise).

3. Should I prioritize J‑1 or H‑1B visa for fellowship?

It depends on your long‑term goals and your profile:

- J‑1:

- More commonly accepted for fellowship.

- Good option if you are open to returning to your home country or taking a J‑1 waiver job afterward.

- H‑1B:

- Better if you want more flexibility to stay in the US long-term.

- Requires Step 3 and a program willing to sponsor.

- Fewer fellowships are open to H‑1B, which can limit your immediate options.

Many non-US citizen IMGs end up on J‑1 for fellowship and then pursue J‑1 waiver jobs or change status later. Discuss your situation with mentors and, when possible, an immigration attorney before making final decisions.

4. Do I need a lot of publications to match into fellowship as an IMG?

Quantity matters less than quality and relevance. For some subspecialties (cards, heme/onc, pulm/CC), having at least a few tangible outputs is very helpful:

- Abstracts at national meetings.

- One or more peer‑reviewed publications.

- A visible role in ongoing projects.

If you have no research at all, it can be a disadvantage, especially for academic programs. But one well-executed, meaningful project with a clear clinical question can be more compelling than five low‑impact, rushed papers. Aim for consistent scholarly engagement rather than chasing numbers.

As a non-US citizen IMG, preparing for fellowship demands extra planning and resilience, but it is absolutely achievable. Start early, align your clinical and scholarly work with your goals, understand the visa and program landscape, and surround yourself with mentors who know both the medical and immigration terrain. Each step you take—even small ones—compounds over time into a strong, compelling application.