Introduction: Why Knowing What Not to Include Matters

Your personal statement is one of the few parts of your application where you control the narrative. Whether you are applying to medical school or residency, this essay allows you to move beyond numbers and bullet points, and show admissions committees who you are, what drives you, and how you think.

Most applicants focus on what they should write: which stories to tell, which achievements to highlight, and how to express their passion for medicine. But an equally important—and often overlooked—skill is knowing what not to include. Even strong candidates can undermine excellent applications with missteps in tone, content, or structure.

This guide serves as a practical admissions guide to the most common pitfalls to avoid in your personal statement, with application tips and concrete writing skills strategies to help you craft a clear, compelling, and professional narrative.

Understanding the Unique Role of the Personal Statement

Beyond Grades and Scores

Applications to medical school and residency are crowded with metrics: GPA, MCAT or USMLE scores, class rankings, research productivity, and evaluation forms. These quantitative markers are important, but they do not convey your character, values, or trajectory. That is the job of your personal statement.

A strong personal statement should:

- Explain why you are pursuing medicine or a specific specialty

- Show how your experiences have prepared you for this path

- Demonstrate reflection, maturity, and self-awareness

- Convey what you will contribute to a medical school class or residency program

What Selection Committees Look For

When admissions committees or program directors read your personal statement, they are asking:

- Does this applicant understand what medicine or this specialty involves?

- Is their motivation thoughtful, sustained, and realistic?

- Do they possess the interpersonal skills, resilience, and professionalism needed?

- Will they work well with patients, colleagues, and the broader healthcare team?

A well-written personal statement answers these questions indirectly through carefully chosen experiences and reflections. Understanding what to leave out helps you keep the focus on these core goals.

Ten Common Personal Statement Mistakes to Avoid

1. Excessive Self-Promotion Without Substance

You must advocate for yourself—but there is a difference between confident representation and empty boasting.

What to avoid:

- Statements like “I am the best candidate for your program”

- Repeatedly noting that you were “the top student,” “the most dedicated,” or “the hardest worker” without context

- Long lists of achievements better suited for your CV

Why it hurts your application:

Admissions committees already see your honors, awards, and publications elsewhere in your application. When you overstate your excellence, you risk coming across as arrogant, insecure, or lacking self-awareness.

Stronger approach:

- Show, don’t tell.

- Use specific examples that illustrate persistence, leadership, empathy, or problem-solving.

- Reflect briefly on what you learned and how it changed your behavior or outlook.

Example:

- Weak: “I am the hardest worker in my class and always get top grades.”

- Strong: “Balancing overnight shifts with exam preparation taught me to prioritize efficiently and seek help early. This shift in strategy not only improved my performance but also allowed me to support classmates who were struggling.”

Here, your work ethic is demonstrated through story and reflection instead of self-congratulation.

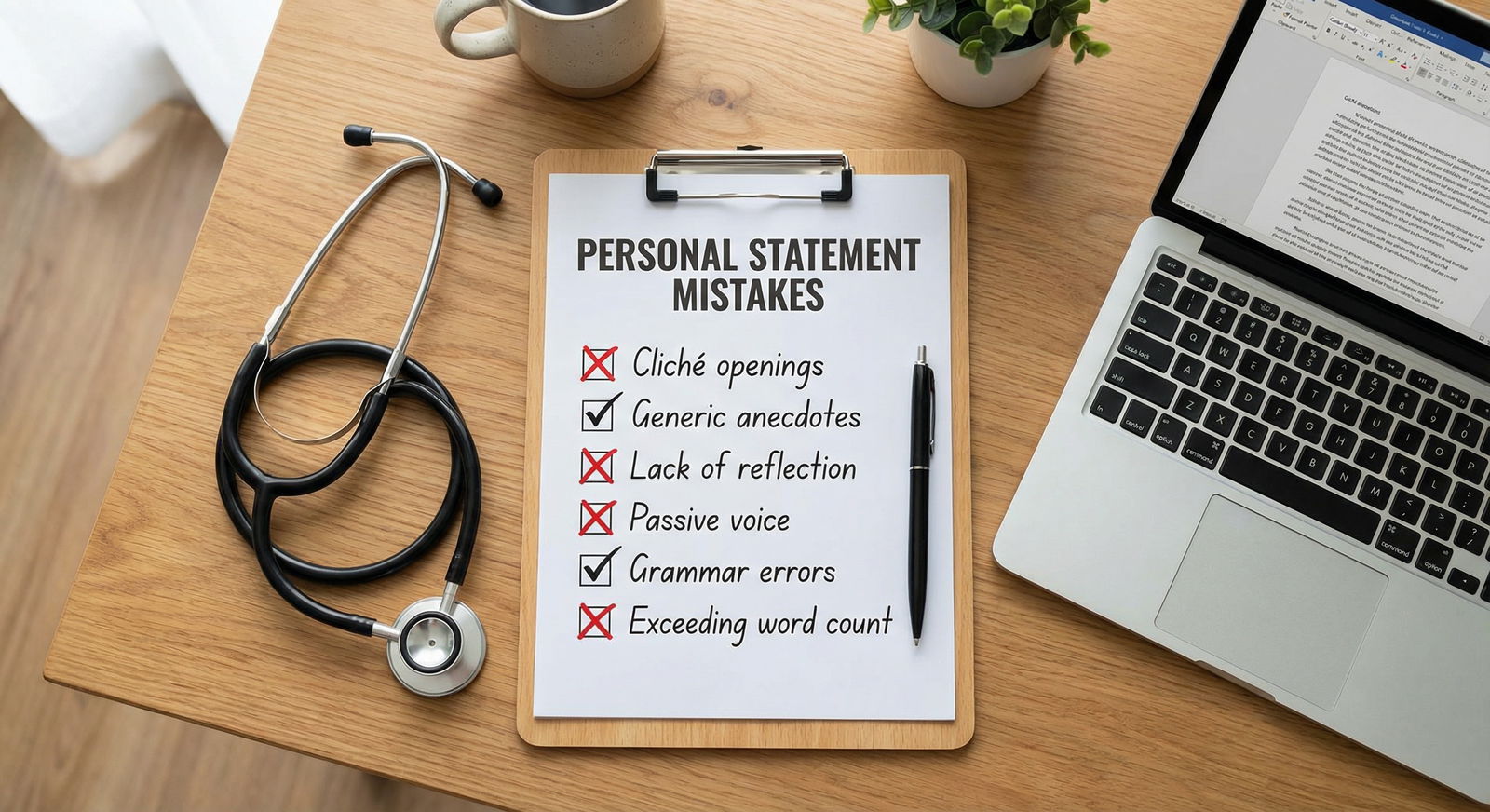

2. Clichés and Overused Phrases That Dilute Your Message

Certain phrases appear in thousands of personal statements each year, especially in medical school and residency applications.

Common clichés to avoid:

- “I have always wanted to be a doctor.”

- “My passion for medicine began when…” without any specific detail.

- “I just want to help people.”

- “This experience changed my life” without explaining how.

These lines signal generic writing and can make your personal statement blend into the crowd.

How to replace clichés with compelling writing:

- Anchor your motivation in specific, concrete experiences.

- Describe what you saw, felt, thought, and learned.

- Focus on your journey, not a template you think admissions wants.

Example transformation:

- Cliché: “I love helping people.”

- Stronger: “During home visits with a community health team, I noticed that many patients were more willing to discuss their concerns at their kitchen table than in the clinic. That experience shaped my belief that trust and context are as important as prescriptions in effective care.”

You are still communicating that you care about helping people, but in a way that is vivid, original, and believable.

3. Negative Experiences Without Demonstrated Growth

Stories of adversity, failure, or struggle can be powerful—if handled thoughtfully. Many applicants wisely choose to write about challenges such as academic setbacks, illness, financial hardship, or personal loss. The problem arises when these stories stop at the difficulty itself.

What to avoid:

- Describing a failure or conflict and ending the story there

- Blaming others (faculty, administration, peers) without taking ownership

- Overly detailed accounts of personal trauma that overshadow your professional identity

- Using the essay primarily to seek sympathy

What admissions committees are looking for:

- Evidence of resilience and coping strategies

- Insight into what you would do differently now

- Growth in maturity, communication, time management, or self-care

- The ability to discuss tough topics in a professional manner

Better framework for challenging experiences:

- Briefly describe the situation

- Acknowledge your role or reaction honestly

- Explain what you learned (skills, mindset shifts, boundaries)

- Show how you have applied those lessons since then

Example:

“After failing an important exam in my second year, I initially felt ashamed and tried to study harder using the same ineffective methods. Meeting with a learning specialist helped me realize I needed to change my approach entirely. I began using active recall, group review sessions, and scheduled breaks. This experience not only improved my academic performance, but also taught me to seek help early—an insight I now apply when managing complex clinical tasks on the wards.”

4. Irrelevant or Unconnected Information

Your personal statement is not a full autobiography. Every paragraph should support your central message: why you are pursuing medicine or a particular specialty, and why you are prepared to succeed.

Examples of irrelevant content:

- Long stories about hobbies without any clear connection to medicine or your growth

- Detailed travel narratives that never relate back to patient care, cultural competence, or teamwork

- Descriptions of high school activities unless they directly inform your current path

- Tangents about politics, religion, or controversial topics that do not directly relate to your role as a future physician

This does not mean you must only discuss clinical or academic experiences. Non-medical experiences can be powerful—if they are clearly linked to relevant skills or perspectives, such as communication, leadership, resilience, or empathy.

How to evaluate relevance:

Ask yourself for each example:

- Does this help the reader understand my motivation, values, or readiness?

- Does it show skills or insights that will make me a better physician?

- Can I clearly tie it back to medicine or my growth as a professional?

If the answer is no, consider cutting it or rewriting to build a clearer connection.

5. Poor Structure, Flow, and Organization

Even strong ideas can be lost in a poorly organized personal statement. Disjointed writing makes you seem less thoughtful and harder to follow—both red flags for a career that depends heavily on communication.

Common structural problems:

- Jumping randomly between time periods or topics

- Including too many unrelated anecdotes with no overarching theme

- Long paragraphs without clear topic sentences

- No introduction that frames your story, or no conclusion that ties it together

A simple structure that works well:

- Introduction: A focused opening that sets the tone and introduces your main theme or motivation.

- Body paragraphs:

- 2–4 key experiences (clinical, personal, research, leadership)

- Each with clear reflection on what you learned and how it shaped your path

- Logical transitions between ideas or time periods

- Conclusion:

- Reinforce your core message and goals

- Look forward to how you will contribute in medical school or residency

Practical writing skills tips:

- Outline before you write: bullet your key points and experiences.

- Use transitional phrases to connect paragraphs (e.g., “Building on this experience…” “Similarly, during…”).

- Read your essay aloud to catch awkward phrasing or abrupt shifts.

- Ask someone who does not know you well if your story feels coherent and easy to follow.

6. Making the Essay Only About You—Not About Patients or the Profession

The personal statement is, by definition, personal—but medicine is fundamentally about others. An essay that centers solely on your ambitions, accolades, or intellectual curiosity, without showing concern for patients or the healthcare team, can feel inward-looking.

What to avoid:

- Never mentioning patients, families, or colleagues

- Focusing entirely on prestige, competitiveness, or lifestyle factors

- Describing medicine only as an academic puzzle or scientific challenge

Stronger elements to include:

- How patient interactions influenced your understanding of the profession

- What you have learned from mentors, nurses, staff, and peers

- How you see your future role in the healthcare team

- Your commitment to patient-centered care, ethical decision-making, or health equity

Example:

Instead of:

“I am drawn to this specialty because it is intellectually challenging and offers complex diagnostic puzzles.”

Try:

“I am drawn to this specialty because it combines intricate diagnostic reasoning with the privilege of guiding patients through vulnerable moments, whether explaining a new diagnosis or discussing treatment options in the context of their values and circumstances.”

This reframing still acknowledges intellectual interest, but situates it within patient care.

7. Ignoring or Minimizing Application Weaknesses

If there are clear questions in your application—such as a term with poor grades, a leave of absence, a gap year, or a professionalism concern—failing to address them at all may raise more concerns than a brief, honest explanation.

What not to do:

- Devote the entire personal statement to explaining a low GPA or test score

- Offer lengthy justifications or blame others

- Use dramatic or highly emotional language about setbacks

More effective approach:

- Address the issue briefly and straightforwardly (often in 2–4 sentences).

- Provide just enough context to be understandable.

- Emphasize insight and improvement: what changed afterwards?

- Then move on to highlight your strengths and growth.

Example:

“During my second year, a family crisis contributed to a temporary decline in my academic performance. With support and improved time management strategies, I was able to return to my previous level of success, as reflected in my subsequent grades and clinical evaluations. This experience taught me to seek help early and reinforced the importance of maintaining healthy boundaries and coping mechanisms in a demanding field.”

If your application system or school provides a separate “adversity” or “additional information” section, consider using that space instead of devoting too much of your main personal statement to remediation.

8. Grammatical Errors and Weak Writing Mechanics

Even the most compelling story loses impact when marred by spelling mistakes, grammar errors, or sloppy formatting. Admissions committees may reasonably wonder: if you are careless with your own narrative, will you be equally careless with patient notes or prescriptions?

Key writing mechanics to watch:

- Spelling and punctuation

- Subject-verb agreement and tense consistency

- Overly long sentences that are difficult to follow

- Informal language, slang, or text-message style

- Repetition of the same word or phrase in close proximity

Practical application tips:

- Use spelling and grammar tools, but don’t rely on them exclusively.

- Set your essay aside for 24–48 hours, then reread with fresh eyes.

- Ask at least two people to review—ideally one who knows you (for content) and one with strong writing skills (for style).

- Read your essay aloud; you will often catch awkward phrasing and rhythm issues.

Strong writing does not mean using the most complex vocabulary. Clear, direct language almost always beats jargon or overly ornate phrases.

9. Generic Language and a Forgettable Tone

Admissions readers encounter hundreds or thousands of personal statements each cycle. Generic language makes it hard for them to remember you.

Signs your essay may be too generic:

- Your essay could plausibly be written by many other applicants.

- You use broad statements like “I am passionate about medicine,” “I love science,” or “I want to make a difference” without specifics.

- You rely on abstract adjectives (“empathetic,” “hardworking,” “dedicated”) instead of concrete examples.

Strategies to make your statement more distinctive:

- Focus on a few key experiences, described in specific detail.

- Include brief, vivid moments (a patient’s question, a mentor’s advice, a turning point).

- Let your natural voice come through—professional but authentic.

- Avoid trying to sound like what you assume “a perfect applicant” sounds like.

You are not trying to impress with drama; you are trying to leave the reader with a clear, grounded sense of who you are as a future physician.

10. Vague or Unspecified Goals and Aspirations

An effective admissions guide will always emphasize this: programs want to see that you have thought concretely about your future. You do not need to have every detail decided—many medical students and residents change paths—but you should be able to articulate where your current interests lie and what kind of physician you hope to be.

What to avoid:

- Ending with a generic sentence like “I look forward to becoming a doctor and helping people.”

- Statements that could apply to any specialty or any program.

- Overly rigid or unrealistic claims (e.g., “I will cure cancer” without context).

Better ways to express your goals:

- Identify specific areas of interest (e.g., primary care, surgical innovation, health disparities, medical education, global health).

- Connect your goals to past experiences that sparked them.

- Emphasize values (e.g., patient advocacy, interprofessional collaboration, community engagement).

Example:

Instead of:

“I want to help people and make a difference in the world.”

Try:

“I am particularly drawn to family medicine because it aligns with my commitment to longitudinal patient relationships and community-level impact. I hope to work in underserved settings, combining direct patient care with advocacy for better access to preventive services.”

This gives the reader a much clearer sense of your direction and how you think about your future role.

Turning Pitfalls into Strengths: Practical Writing Strategy

Avoiding these personal statement mistakes is only half the battle. To turn your essay into a compelling narrative:

- Start early. Give yourself weeks—not days—to draft, revise, and refine.

- Brainstorm widely, then narrow. List experiences and themes; then choose the few that best showcase your readiness and fit.

- Focus your theme. Decide what central message you want the reader to take away about you.

- Draft freely, edit ruthlessly. Your first draft may be too long and unfocused; revision is where clarity and power emerge.

- Seek targeted feedback. Ask mentors, advisors, or residents for content-level feedback; writing centers or peers for style and clarity.

- Customize when appropriate. For residency, you may adjust parts of your statement to better fit specific specialties or combined programs.

Thoughtful, disciplined writing is itself evidence of the professionalism and communication skills programs value.

FAQ: Common Questions About Medical Personal Statements

1. What should be the main focus of my personal statement?

Your personal statement should center on three core elements:

- Motivation: Why you are pursuing medicine (or a specific specialty).

- Preparation: How your experiences—clinical, academic, research, leadership, or personal—have prepared you.

- Projection: What kind of physician you hope to become and how you will contribute to a medical school or residency program.

Everything you include should support one or more of these areas. Avoid turning your essay into a full CV in paragraph form; instead, choose selected experiences that best illustrate your journey and growth.

2. How long should my personal statement be?

Length depends on the application system:

- Medical school (AMCAS): Up to 5,300 characters (including spaces).

- Most MD/DO secondary essays: Vary by school; always check instructions.

- Residency (ERAS): Typically, one page when pasted into the ERAS text box (roughly 3,500–4,000 characters is a common practical target).

Aim to use most of the allotted space without filling it with fluff. Concise, well-structured writing is more effective than reaching the character limit just for the sake of length.

3. Should I mention my GPA, MCAT, USMLE scores, or specific grades in the personal statement?

Generally, no. Numerical data already appears elsewhere in your application. The personal statement is for context and narrative, not repetition of statistics.

The exception: if you are briefly addressing an academic difficulty (e.g., a failed exam or term), you may reference it in general terms while emphasizing what you learned and how you improved. Keep this section short and focused on growth, not justification.

4. Is it appropriate to use humor in a medical personal statement?

Light, subtle humor can sometimes highlight your personality, but it is risky:

- Admissions committee members differ in their sense of humor.

- Jokes, sarcasm, or casual language can be misinterpreted.

- Humor about sensitive topics (patients, illness, mental health, culture, religion, politics) is especially inappropriate.

If you use humor at all, keep it minimal, professional, and never at anyone’s expense. A warm, human tone is safer and more effective than trying to be funny.

5. How many drafts should I write before finalizing my personal statement?

There is no magic number, but strong essays typically go through multiple rounds of revision:

- Brainstorm draft: Get ideas down without worrying about perfection.

- Structural draft: Organize into a clear beginning, middle, and end.

- Content refinement: Sharpen key stories and reflections; remove tangents.

- Style and clarity edits: Improve transitions, sentence flow, and word choice.

- Proofreading pass: Eliminate errors and polish formatting.

Most applicants benefit from at least 3–5 drafts. Build revision time into your application timeline so you are not rushing at the last minute.

By understanding what not to include in your personal statement—and why—you're already ahead of many applicants. Combine these application tips with honest self-reflection and careful writing, and you will create a personal statement that is clear, authentic, and memorable to admissions committees.