Most candidates walk into residency interviews with scattered memories; the strong ones walk in with a story arsenal.

You are not winging this if you care about where you match. You are building a structured bank of 15 reusable, high‑yield stories that can answer almost any question they throw at you.

Let me break this down specifically.

Why “15 Stories” Is The Sweet Spot

You do not need 80 stories. You need about 15 well‑built ones that are:

- Versatile (can answer multiple question types)

- Detailed (specific actions, not vague “I learned a lot”)

- Polished but not robotic (you sound prepared, not scripted)

Here is the logic. Interview questions fall into predictable buckets:

- Teamwork / conflict

- Leadership

- Failure / mistake

- Ethical dilemma

- Difficult patient / family

- Dealing with stress / burnout

- Feedback and growth

- Time management / prioritization

- Diversity / working with different backgrounds

- Handoff / communication error / safety

- Advocacy / going above and beyond

- Systems issue / QI / process improvement

- Personal challenge / resilience

- Teaching / mentoring

- Career motivation / why this specialty

If you intentionally build stories to cover each of these buckets, you can remix them on the fly to handle 90% of questions.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Teamwork/Conflict | 12 |

| Leadership | 10 |

| Failure/Mistake | 9 |

| Ethics | 6 |

| Difficult Patient/Family | 11 |

| Stress/Burnout | 8 |

| Feedback/Growth | 9 |

| Time Management | 7 |

| Diversity | 6 |

| Safety/Communication | 10 |

| Advocacy/QI | 8 |

| Resilience | 9 |

| Teaching | 7 |

| Motivation | 6 |

| Other | 5 |

Notice: each story can cover multiple categories. One ICU night shift story might hit teamwork, time management, and stress management all at once.

Step 1: Map Your 15 Story “Slots”

First, you need the framework. Then you fill it.

The Actual 15‑Story Blueprint

Use this as your template. You will tailor, but do not skip categories unless you genuinely lack experience there.

- A high‑impact teamwork story

- A real conflict with a peer or nurse that ended constructively

- A leadership story with concrete outcomes

- A meaningful failure/mistake and what changed afterward

- An ethical dilemma (capacity, disclosure, resource allocation, etc.)

- A difficult patient or family interaction that you improved

- A time you were overwhelmed and how you handled stress/burnout

- A time you received hard feedback and changed behavior

- A time you had to prioritize multiple sick patients / competing demands

- A story involving diversity, bias, or working across differences

- A communication breakdown or near‑miss safety event and how you responded

- A time you advocated for a patient or fixed a systems problem (QI flavor)

- A non‑clinical resilience story (personal setback, immigration, finances, illness)

- A teaching/mentoring story (junior, peer, patient teaching)

- A story that explains “why this specialty” in a lived, not theoretical, way

Print that list. Literally. This is your scaffolding.

A quick sanity check: if your current experiences are 90% research and one outpatient rotation, you have a problem. Not because research is bad, but because your stories will feel one‑dimensional. This exercise exposes that early, when you can still mine other rotations or life experiences.

Step 2: Pull Raw Material From Your Actual Life

You are not inventing stories. You are excavating them.

Where to Look Clinically

Go rotation by rotation:

- Internal Medicine: multi‑problem patients, social complexity, discharges gone sideways, overnight cross‑coverage, code strokes, goals‑of‑care talks.

- Surgery: OR communication, time pressure, pre‑op vs post‑op coordination, consent issues, angry families, handoffs.

- Pediatrics: guardians vs patient wishes, child protection issues, vaccine refusal, school/social work coordination.

- OB/GYN, Psych, EM, FM: capacity questions, domestic violence, substance use, patients leaving AMA, resource limitations at night.

For each rotation, ask yourself three questions:

- When did something go wrong or almost go wrong?

- When did I feel proud of how I handled something hard?

- When did I walk away thinking, “I will not forget this case”?

Those are your raw stories.

Non‑Clinical Gold You Are Probably Underusing

Some of your strongest residency interview stories will be non‑clinical. Programs want to know if you can handle life, not just medicine.

Think about:

- Long‑term commitments: coaching, tutoring, EMS, military, caregiving.

- Real adversity: immigration, major illness, financial pressure, being first‑gen, supporting family while in school.

- Work experience: restaurant, retail, manual labor, startup, teaching.

- Competitive or team activities: athletics, music, debate, research teams.

Non‑clinical stories are often perfect for:

- Resilience

- Time management

- Conflict

- Leadership

- Diversity / working across cultures

| Story Type | Best Source Examples |

|---|---|

| Teamwork/Conflict | Wards, OR, coaching, group projects |

| Leadership | Student orgs, QI projects, coaching, lab |

| Failure/Mistake | Rotations, exams, research errors |

| Resilience | Personal hardship, illness, immigration |

| Teaching/Mentoring | TA roles, tutoring, peer teaching, patients |

If all 15 stories are hospital‑based, you will sound like a robot who only lives on the wards. That is not impressive. It is one‑dimensional.

Step 3: Force Every Story Into a Clean Structure (But Not Cookie‑Cutter)

Unstructured stories are what derail otherwise strong candidates. They ramble, they drown in medical detail, and they never actually answer the question.

Use a modified STAR format: Context – Challenge – Action – Result – Reflection. Short labels. High discipline.

The 5‑Component Story Spine

For each story, you should be able to hit:

Context – 1–2 sentences

Where were you? What was your role? What was the setting?Challenge – 1–3 sentences

What was the specific problem, tension, or decision? Make it concrete.Action – 3–6 sentences

What did you do? Stepwise. Focus on decisions, communication, and reasoning.Result – 1–3 sentences

What changed because of your actions? Clinical, relational, or systems outcome.Reflection – 2–4 sentences

What did you learn, and how did it change what you do now?

Example: Teamwork Story Skeleton

Context:

“I was a third‑year on my IM ward rotation at a large county hospital, covering a five‑patient list on morning rounds.”

Challenge:

“On one particularly busy morning, we admitted a patient with decompensated heart failure at the same time another patient became hypotensive post‑paracentesis. The resident was tied up in a rapid response, and the intern looked overwhelmed trying to juggle both.”

Action:

“I quickly reviewed both charts and prioritized the hypotensive patient. I notified the nurse that I was concerned this might be bleeding, helped get a stat CBC and bedside ultrasound, and called the cross‑cover resident with a focused update. While labs were pending, I coordinated with another student to gather admission info on the new heart failure patient so the intern would not lose that data. I made sure we documented events in real time, and I checked back with the nurse to reassess vitals after each intervention.”

Result:

“The resident was able to step in with a clear picture of what had happened, the patient stabilized with fluids and blood products, and we avoided an ICU transfer. The intern later said that having the admission pre‑organized and the data clearly summarized prevented them from missing key information.”

Reflection:

“That day taught me that teamwork is about proactive communication and stepping into gaps without waiting to be asked. Now, whenever I see the team getting stretched, I ask what piece I can own and try to anticipate information people will need before they ask for it.”

Notice: you can use that same story for teamwork, prioritization, communication, “working under pressure,” “time you went above your role,” and “how do you handle a busy service?”

Step 4: Make Stories Reusable Across Multiple Question Types

This is where people either get efficient or drown. You want multi‑use stories.

Build “Tags” for Every Story

For each of your 15 stories, assign 3–5 “tags” that describe which question types it can answer.

Example story tags:

Teamwork on night float with cross‑cover calls

Tags: teamwork, prioritization, stress, communication, leadership (micro)Patient refusing dialysis

Tags: ethics, difficult patient, communication, cultural sensitivity, systems issuesFailing an exam and remediating

Tags: failure, feedback, resilience, time management, self‑improvement

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| 1 Tag | 1 |

| 2 Tags | 3 |

| 3 Tags | 6 |

| 4+ Tags | 5 |

You want most stories in the 3–4+ tag range. If a story only covers one specific niche, it is low value unless that niche is absolutely critical.

Concrete Example of Reuse

Take this scenario: you were part of a QI project reducing CT scans for minor head trauma.

You can use it to answer:

“Tell me about a time you led a project.”

Focus: your role organizing meetings, data collection, convincing skeptics.“Tell me about a time you faced resistance.”

Focus: senior attendings questioning guidelines, how you built buy‑in.“Tell me about a time you improved a system for patients.”

Focus: reduction in wait times, cost, unnecessary radiation.“Give an example of working with people from different backgrounds.”

Focus: radiology, ED nurses, admin leadership all with different priorities.

Same raw story. Four very different question framings.

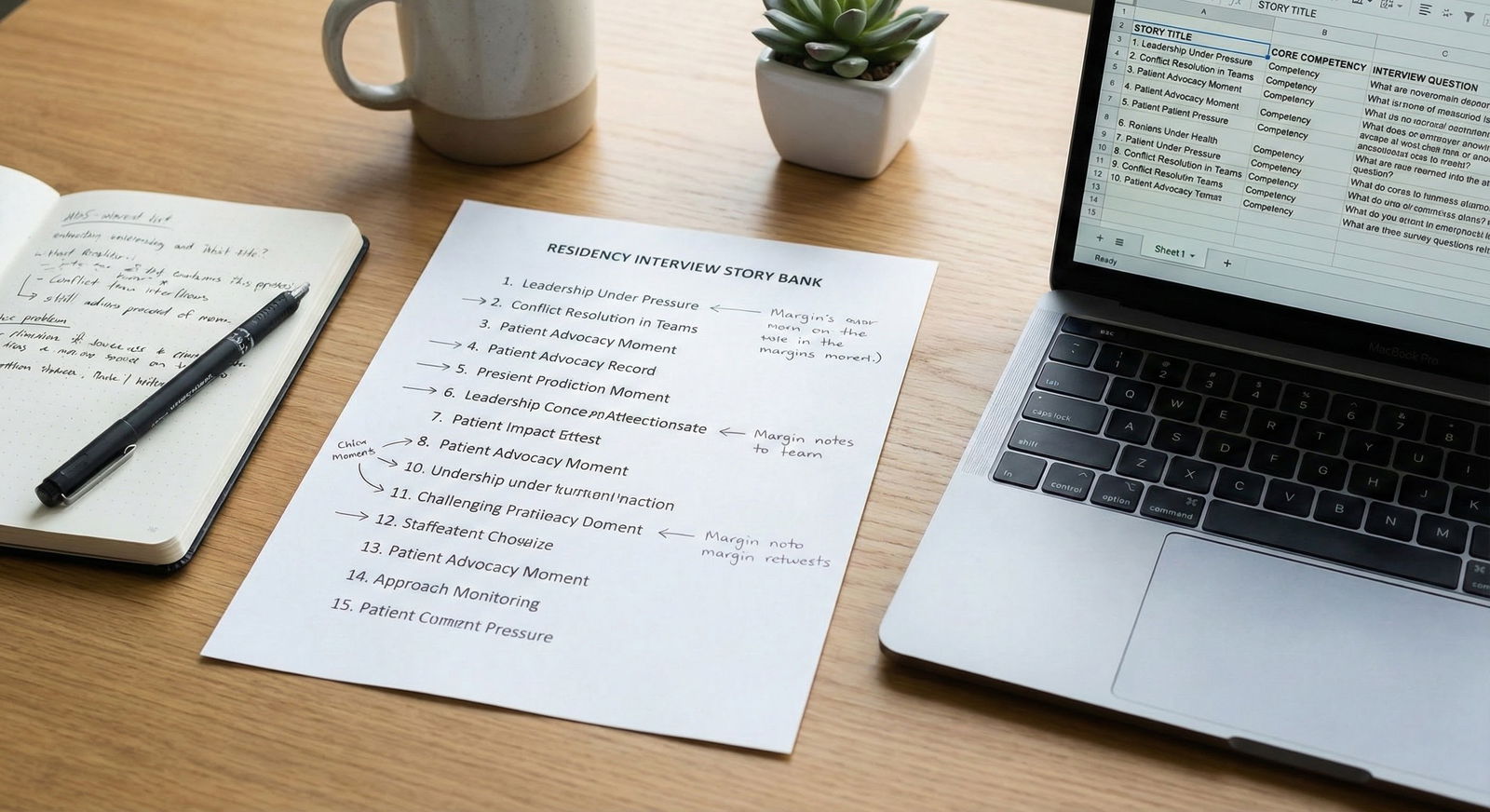

Step 5: Actually Document This Like A Serious Person

If it is not written down, it does not exist under stress. Your brain will fail you at 6 a.m. pre‑interview.

Use a Simple Story Bank Spreadsheet

Create a spreadsheet with columns like this:

| Column | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Story # / Name | Quick reference label |

| Type / Category | Primary bucket (e.g., Teamwork, Failure) |

| 3–5 Tags | Other question types it can answer |

| One-Line Hook | 1-sentence summary |

| Context | 1–2 sentences |

| Challenge | 1–3 sentences |

| Action | 3–6 bullet points or sentences |

| Result | 1–3 sentences |

| Reflection | 2–4 sentences |

| Clinical/Nonclinical | Helps balance your set |

Anywhere you cannot map a question to at least one story, you have a gap. Either:

- You genuinely lack that experience → you need a non‑clinical substitute or a future example from an upcoming rotation.

- You have the experience but never encoded it as a story → add it as story #16 and see if one of your weaker ones can be retired.

Step 8: Avoid The Common Story Mistakes That Sink Otherwise Good Applicants

Here is where people get careless.

Mistake 1: The “Group Project” Story Where You Do Nothing

If your story could be told without you in it, it is useless. Interviewers are evaluating your behavior, not the existence of a nice team.

Fix:

In every story, be crystal clear:

- What exactly did you decide?

- What exactly did you say?

- What exactly did you notice or initiate?

If you find yourself saying “we” in every sentence, rewrite it.

Mistake 2: The Fake Failure

“I care too much.” “I work too hard.” That sort of nonsense. Attendings have heard it a thousand times.

A real failure might be:

- You misunderstood a task and dropped the ball.

- You overcommitted to multiple projects and under‑delivered.

- You handled a conflict poorly at first (avoid name‑calling but be honest about your misstep).

The key is clear ownership and specific change. If the “lesson learned” is a Hallmark card, you did not go deep enough.

Mistake 3: Blaming Others Overtly

You can acknowledge systemic problems and difficult supervisors. But if every story is “my attending was unreasonable” or “nurses were not cooperative,” you look like the problem.

Reframe:

- Describe constraints and miscommunications.

- Own your part, even if small.

- Focus on how you improved communication or advocated more effectively.

Mistake 4: Ethical Stories With No Ethical Reasoning

Ethical questions are not solved by “I just followed the attending.” That is not an answer.

You need to show:

- You understood the conflict (autonomy vs beneficence, confidentiality vs safety, justice/resource allocation, etc.)

- You sought input appropriately (supervisor, ethics consult, social work).

- You would handle similar cases with a structured approach.

If you cannot name the actual tension, the story is not doing its job.

Step 9: Integrate Your Stories With “Why This Program” And “Why This Specialty”

A lot of people treat these as separate domains. They are not.

Your best “why this specialty” answer is usually a story, not a philosophy. For example:

- A continuity clinic patient that made outpatient care meaningful.

- A trauma patient in EM that crystallized why you like acute, undifferentiated problems.

- A psych case that changed how you see chronic mental illness.

Your best “why this program” answer weaves:

- Specific program features (X clinic, Y patient population, Z curriculum)

- With your lived experiences (your stories) that show you will actually use those features.

Example:

- Story: You ran a student clinic for uninsured patients with language barriers.

- Program link: Program has a robust refugee clinic and interpreter services.

- Bridge: “I have seen how language and documentation status block access to care. At my student‑run clinic, I… [brief story]. Your refugee clinic and the longitudinal community health track stand out because I can continue that work at a more sophisticated level.”

Again, a story, repurposed.

Step 10: Rehearse Under Realistic Conditions, Not Just In Your Head

You can read your spreadsheet all day. It will not translate into live performance unless you stress it.

Three Levels of Practice

Solo practice with recording

- Answer 5 random questions pulled from a list.

- Do not pause to plan. Just go.

- Listen back. Check: did you actually answer the question? Did you pick an appropriate story?

Peer or mentor mock interview

- Send them a broad list of potential questions, not your stories.

- Have them pick randomly and mix in unexpected follow‑ups:

- “What would you do differently now?”

- “How did your team see you after that?”

- “Give me another example of handling conflict.”

- This forces you to reuse stories creatively without sounding repetitive.

Timed, back‑to‑back cases

- 20–25 minutes.

- Rapid‑fire: they ask, you answer short‑form (45–60 seconds).

- The point is to build speed in selecting an appropriate story quickly.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Story Brainstorming | 4 |

| Structuring & Writing | 4 |

| Solo Practice | 3 |

| Mock Interviews | 3 |

You are looking for two things: your default “go‑to” stories, and the ones you keep avoiding. You will inevitably have 4–5 “anchors” that come up a lot; that is fine. Just make sure the others are sharp enough to use when needed.

Step 11: Handle Curveball Questions With Story Fragments

Some questions are weird. “If you were a fruit, what kind would you be?” Or, “Tell me something not on your application.”

Your story bank still helps. You are just using fragments instead of the full spine.

For “something not on your application”:

- Grab a non‑clinical resilience or personal interest story from your bank and shorten it.

- Focus less on the challenge and more on what it reveals about your personality, values, or habits.

For “what is your biggest weakness”:

- Pull from your failure/feedback stories.

- Use the same structure, compressed.

- Do not pick a weakness that is core to residency (e.g., “I am bad at time management” with no strong remediation).

For “teach me something in 2 minutes”:

- Use your teaching story as a template.

- You already know how to break down a concept; pick something from your hobby, research, or medicine that is accessible.

You are not improvising from zero. You are recombining pieces you have already thought through.

Step 12: Update The Bank As Interview Season Progresses

Your first few interviews will reveal which stories land and which ones feel flat. Treat this as data, not shame.

After each interview day, jot down:

- Questions you did not expect.

- Moments where you wished you had picked a different story.

- Stories that clearly resonated (interviewer wrote notes, asked follow‑ups, looked engaged).

Refine:

- Tighten or retire weak stories.

- Add a new one if a gap keeps showing up.

- Adjust which story you use for which type of question as you see what feels natural.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Interview |

| Step 2 | Debrief Notes |

| Step 3 | Identify Weak or Strong Stories |

| Step 4 | Revise or Replace Stories |

| Step 5 | Update Tags & Spreadsheet |

By mid‑season, your stories should feel almost automatic. Not because you memorized lines, but because you have used these cases to think hard about who you are as a future resident.

The Bottom Line

Three things if you remember nothing else:

- Fifteen well‑structured, multi‑tag stories will cover almost every residency interview question you are actually going to get.

- Every story must show your decisions, actions, and growth—if the team could have told it without you, fix it.

- Write the stories down, tag them, rehearse them under time and stress, and keep iterating as interviews go on.

Do this properly and you will not walk into interviews hoping your memory saves you. You will walk in with a bank. A bank you have already stress‑tested, refined, and learned from.