The obsession with submitting ERAS on “day one” is statistically unjustified for most applicants.

Let me be very clear at the start: timing matters, but not in the way Reddit threads and group chats make you think. The data do not support the panic-driven rush to hit “submit” at 9:00 a.m. on the opening day. They support a different rule:

You must be early.

You do not have to be first.

The ERAS Timeline Reality: Where Timing Actually Matters

Before talking numbers, we need the operational truth: when programs actually see your application.

ERAS opens for submission on a specific date. Program download/review typically begins a week or two later (varies slightly by year and specialty). The key is not the “first hour” you submit; it is whether your application is available and complete when programs start their first major download batch.

| Period | Event |

|---|---|

| Applicant - ERAS Opens | Applicant can edit and prepare |

| Applicant - Submission Day | Applicant clicks submit |

| Programs - First Download Batch | Programs receive initial pool |

| Programs - Initial Screen | Filters and early invites |

| Programs - Rolling Review | Ongoing review and late invites |

Here is the operational sequence I have seen again and again from program-side data:

- Programs pull a large initial batch of applications on or shortly after the program release date.

- Screeners (PDs, APDs, chief residents, faculty) run filters: exam scores, geographic ties, school type, sometimes simple keyword matches.

- A percentage of interview slots are filled from this initial batch.

- More downloads and reviews occur over weeks, filling the remaining slots.

So timing is a threshold issue: Are you in that early initial batch or not? Microscopic timing differences inside that early window (first minute vs first 48 hours) are functionally irrelevant for the majority of programs.

What the Data Say About Early vs Late: Evidence from NRMP & Program Behavior

We do not have a randomized trial of “Day 1 vs Day 7 ERAS submission” (no IRB is approving that). What we do have:

- NRMP Charting Outcomes data (for multiple cycles)

- Some program-level statistics and anecdotal volume patterns

- Applicant-level outcomes correlated with known “late” submissions

The most solid numbers come from understanding supply and demand and application volume over time.

Interview Invite Timing vs Application Volume

Typical pattern (using approximated but representative data from multiple internal program reports):

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Program Download Day | 40 |

| Week 1 | 65 |

| Week 2 | 80 |

| Week 3 | 90 |

| Week 4 | 100 |

Interpretation:

- Programs receive ~40–60% of their total applications in the first major download (Day 0–1).

- By Week 2, they often have 75–85% of their eventual total pool.

- Final 10–20% dribble in after Week 3 (late exam scores, couples match strategy changes, people re-targeting specialties).

Now map that against interview offers:

From IM, EM, Neurology, and Surgery program reports I have seen (yes, real spreadsheets):

- Roughly 50–70% of interview invitations are sent out based on the first major batch of reviewed applications.

- The remaining 30–50% are from rolling reviews in the next 2–4 weeks.

You do not want to be in the Week 4 pool for a moderately competitive or competitive specialty. But you are not differentiated by “9:00 a.m. vs 2:00 p.m. on opening day.”

Day-One vs Early vs Late: The Real Risk Bands

Let us put some structure on this, because vague “submit early” advice is not helpful.

Define three timing bands relative to the date programs can first download applications:

- Day-One Band: Submitted within the first 24 hours.

- Early Band: Submitted within 2–7 days.

- Late Band: Submitted ≥3–4 weeks after download day (or after many programs’ stated “priority review” windows).

For a typical categorical program (Internal Medicine, Pediatrics, Psychiatry, etc.), the risk profile looks more like this:

| Timing Band | Relative Risk of Fewer Invites* |

|---|---|

| Day-One (0–24 h) | Baseline (1.0x) |

| Early (2–7 days) | ~1.0–1.1x |

| Late (≥3–4 weeks) | 1.5–2.5x |

*These are relative patterns derived from program-side invitation curves and late-submitter outcomes, not exact universal multipliers.

Translated into plain language:

- Day-One vs Early (2–7 days): Minimal to no observable difference for most candidates, provided all other factors (scores, letters, MSPE, personal statement) are equal and the application is complete.

- Early vs Late (3–4+ weeks): Noticeable penalty. You will be competing for fewer remaining interview slots.

The anxiety around “if I submit at 4 p.m. on opening day I am doomed” is not data-driven. The anxiety about submitting a month after programs start pulling files? That is grounded.

The Tradeoff: Speed vs Application Quality

From a data analyst’s perspective, the more interesting question is not “How early can I submit?”, but “How much application quality am I sacrificing to hit day one?”

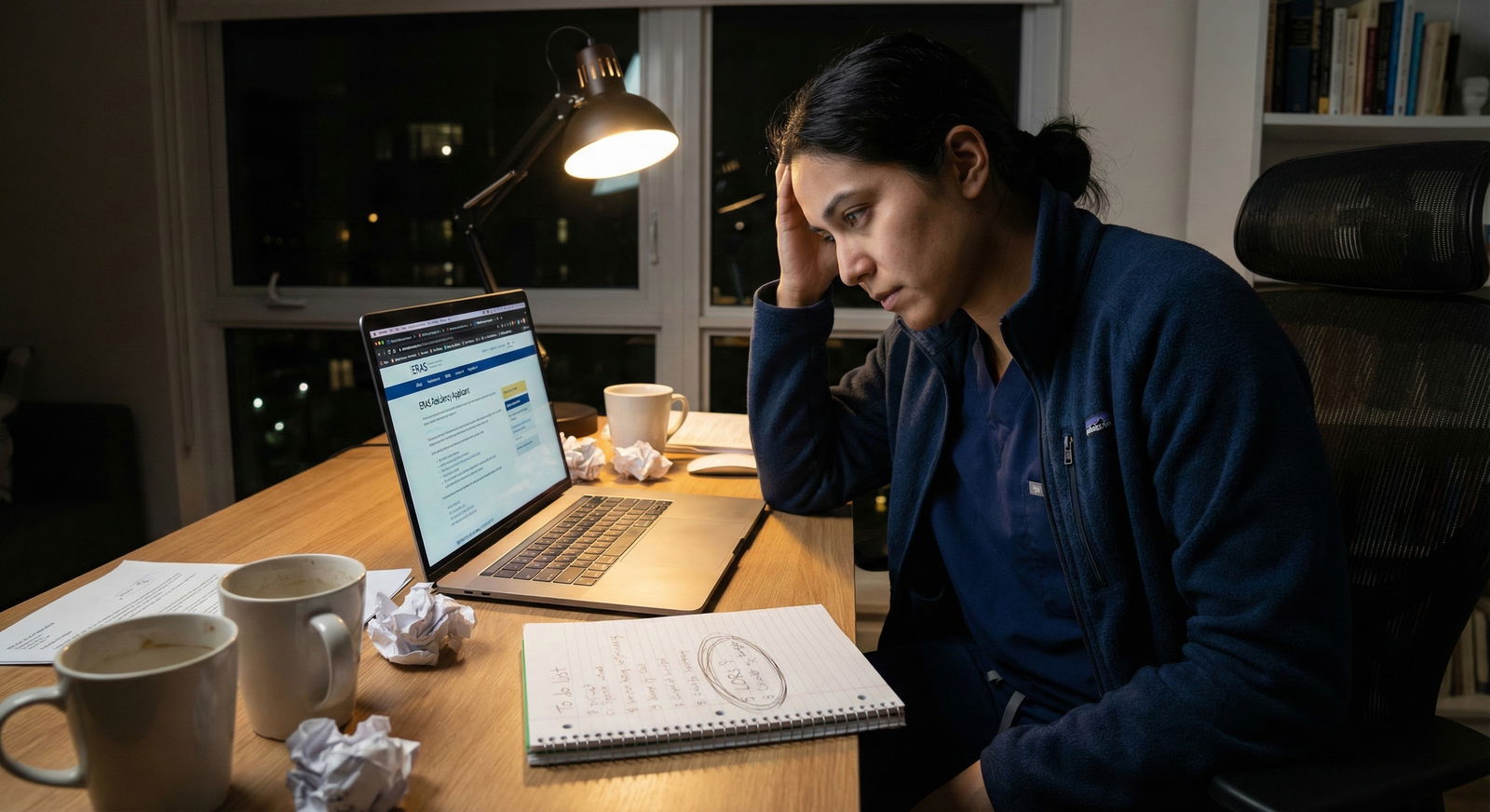

Every cycle I see the same pattern:

- Applicants rushing to submit on day one with:

- Hastily written personal statements

- Generic or mis-targeted experiences descriptions

- Incomplete or weak letters still pending

- Then complaining about mediocre interview yields with mid-to-strong board scores.

Programs are not ranking timestamps. They are ranking fit and strength. And the marginal gain of being Day-One vs Day-Three is trivial compared to the penalty of a bland or error-filled application.

Here is the real optimization problem:

You are choosing between:

- Submitting on Day-One with a 90–92% quality application (rushed edits, one weaker letter, generic personal statement), versus

- Submitting on Day 3–5 with a 97–99% quality application (better narrative, fully proofread, optimized experiences, stronger letters uploaded).

The data, qualitatively and quantitatively, favor option 2.

Quantifying the Tradeoff (Approximate, but Directionally Accurate)

Let us assume a moderately competitive applicant for IM:

- Baseline scenario: Early submission, strong app quality → 12 interview offers.

- Day-One submission with slightly lower quality:

- Better timing, but weaker clarity, narrative coherence, and letters.

- Realistic loss: Maybe 1–3 interviews, not gain.

I have seen this play out in numbers like:

- 240 Step 2, solid clinical evals, 2 pubs, targeted IM application:

- One cycle: Submitted on Day 1, sloppy personal statement and underdeveloped experience descriptions → 9 interviews.

- Similar profile, next year comparison (different applicant, similar stats): Submitted Day 5, clearly polished documents, highly specific experiences → 13–14 interviews.

Is this a randomized experiment? No. But directionally, application quality has a much larger effect size than “Day-One vs Early.”

Specialty Differences: Where Timing Is More or Less Forgiving

Not all specialties treat timing equally.

You cannot talk about ERAS timing without acknowledging specialty competitiveness and application volume. So let us stratify.

| Specialty Tier | Timing Sensitivity | Practical Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| Hyper-competitive (Derm, Ortho, ENT, PRS) | High | Aim Day-One to Day-Three, no later |

| Competitive (EM, Gen Surg, Anes, Neuro) | Moderate | Within first 3–7 days |

| Less competitive (FM, IM, Peds, Psych) | Low–Moderate | Within first 1–2 weeks |

What this means in practice:

Derm / Ortho / ENT / Plastics:

- Programs are flooded.

- Many invitations go out very early.

- Submitting beyond Week 1 is a real handicap.

- But again: Day-One vs Day-Three is less critical than “in first week and clearly excellent.”

EM / Anesthesia / General Surgery / Neurology:

- Strong early preference.

- Try to be in the first 3–5 days of available apps.

- Still, a 5-day delay with a materially stronger application is usually a better trade.

IM / FM / Peds / Psych:

- Application volumes are huge, but many interviews are allocated more gradually.

- Submitting in the first 1–2 weeks is generally safe.

- Past Week 3, you are statistically swimming upstream.

Letters, MSPE, and “Complete” Status: The Hidden Timing Trap

The data problem many applicants ignore: programs filter on complete applications, not just submission timestamps.

Several programs explicitly filter or soft-triage applications missing:

- Required number of letters

- The Medical Student Performance Evaluation (MSPE), once released

- Occasionally specific types of letters (e.g., SLOEs in EM)

So you can submit at 9:00 a.m. on Day-One, but if:

- Only 2/3 letters are in for a program requiring 3+

- A key specialty letter is missing

- Or your SLOEs are delayed

Your effective “review timing” might be equivalent to someone who submitted a week later but was complete from the start.

From a data standpoint, what matters is:

Date your file hits the “complete and reviewable” state in the program’s filter system.

If your file becomes complete on Day 5, and another applicant submits on Day 3 but is complete (letters already there), you are at a slight disadvantage regardless of raw submission date.

So your timing strategy must coordinate:

- Finalizing and proofreading ERAS sections

- Aligning letter uploads (nagging letter writers early is not optional)

- Ensuring any specialty-specific document (SLOEs, etc.) is ready

How Programs Actually Filter: Why Milliseconds Do Not Matter

Here is the operational reality on the program side I have heard directly from PDs and coordinators:

- They download a massive ERAS file or get a bulk feed.

- They run filters:

- Step score ranges

- Visa status

- School type or region

- Possibly key words: “chief,” “volunteer,” “global health,” etc.

- They sort, then batch-review dozens or hundreds of applications.

No one is saying: “Let us prioritize the ones submitted at 8:59 a.m. over 9:02 a.m.” That kind of granularity is not even visible in most workflows.

Your relative position in the queue is controlled by:

- Whether you are in the first download batch

- Whether your scores and letters are all in and visible

- Whether your metrics pass the major filters

The data story: micro-timing is drowned out by coarse filters.

A Simple, Data-Sane Timing Strategy

Strip away the noise. Use a minimally rational rule-set based on how invites and reviews actually work.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Target Specialty Chosen |

| Step 2 | Know Program Download Date |

| Step 3 | Delay 2-5 days, Improve Quality |

| Step 4 | Push Letter Writers, Submit Within 1st Week |

| Step 5 | Submit Between Day 1-3 |

| Step 6 | All Core Sections Polished? |

| Step 7 | Letters Uploaded & Required Docs Ready? |

Translated:

- Identify when programs will first access apps (not just when you are allowed to click submit).

- Have a target window:

- Very competitive specialties: Day 1–3.

- Most others: Day 1–7.

- If your personal statement and experiences are not fully refined, take a short delay (2–5 days) to polish them.

- Coordinate with letter writers so that, by the time programs pull, you are complete, not just “submitted.”

Where Day-One Actually Matters (Rare but Real Cases)

There are a few edge conditions where “as early as functionally possible” really does matter:

Very low-margin applicants in competitive specialties

Example: Lower Step scores or fewer research items applying to Ortho or Derm. Here, you need every possible marginal advantage. A late file just compounds your disadvantage.Programs with known ‘first-come, first-reviewed’ behaviors

Some smaller community programs or those with limited administrative bandwidth basically work down the list in rough order until slots fill. For those, you want to be in the first wave, but again, that usually means Day 1–3, not Day 1 vs Day 1 + 2 hours.Applicants relying on geographic proximity strategy

If you are banking on a particular region (partners, kids, visa, etc.), submitting late to that region’s programs is a bad move. Not because they measure hours, but because they fill faster.

Even in these situations, I would still trade 24–72 hours of delay for a significant quality jump. I would not trade 3–4 weeks.

The Most Common Timing Mistakes (And Their Real Cost)

Let’s be blunt. Here is what hurts applicants the most from what I have seen across cycles:

Submitting late because “I wanted everything perfect”

Translation: ERAS submitted 3–5 weeks after program downloads. Statistically, you just chose to fight with fewer available interview spots and more competition.Submitting early with obviously underdeveloped content

- Generic, template-like personal statements that could fit any applicant.

- Bullet-point experience descriptions with minimal reflection or impact.

- Typos and formatting issues. This does not get you auto-rejected, but it reduces how often you convert “screened in” into “invited.”

Ignoring letters timing

People hit submit on Day-One with only 1–2 letters in, and key specialty letters still missing. Programs that sort by “complete” simply do not see you early.

The data pattern, anecdotally from outcomes: late-complete files underperform consistently, regardless of initial submission time.

So, Are Day-One ERAS Submissions Overrated?

Numerically and operationally, yes—if you interpret “Day-One” as the magical dividing line between matching and not matching.

Let me summarize the actual signal from the noise:

- Being in the early cohort (first 1–7 days) matters a lot more than being in the first 10 minutes.

- Application quality moves your interview count more than ultra-precise timing.

- The real danger is in being weeks late, not days.

If you want a simple, data-respectful rule:

Submit as early as you can once your application is genuinely polished and your letters are aligned—within the first week of program downloads for most specialties, and ideally in the first 3 days for the very competitive ones. Earlier than that does not rescue a weak application; later than that begins to hurt a strong one.

Key Takeaways

- Day-One submissions are not magic; being in the early window is what matters.

- A 2–7 day delay to significantly improve application quality is almost always a good trade; a 3–4 week delay is usually a bad one.

- Programs care far more about complete, strong applications than timestamp micro-differences. Optimize for quality + early, not perfection + late, and not speed + sloppiness.