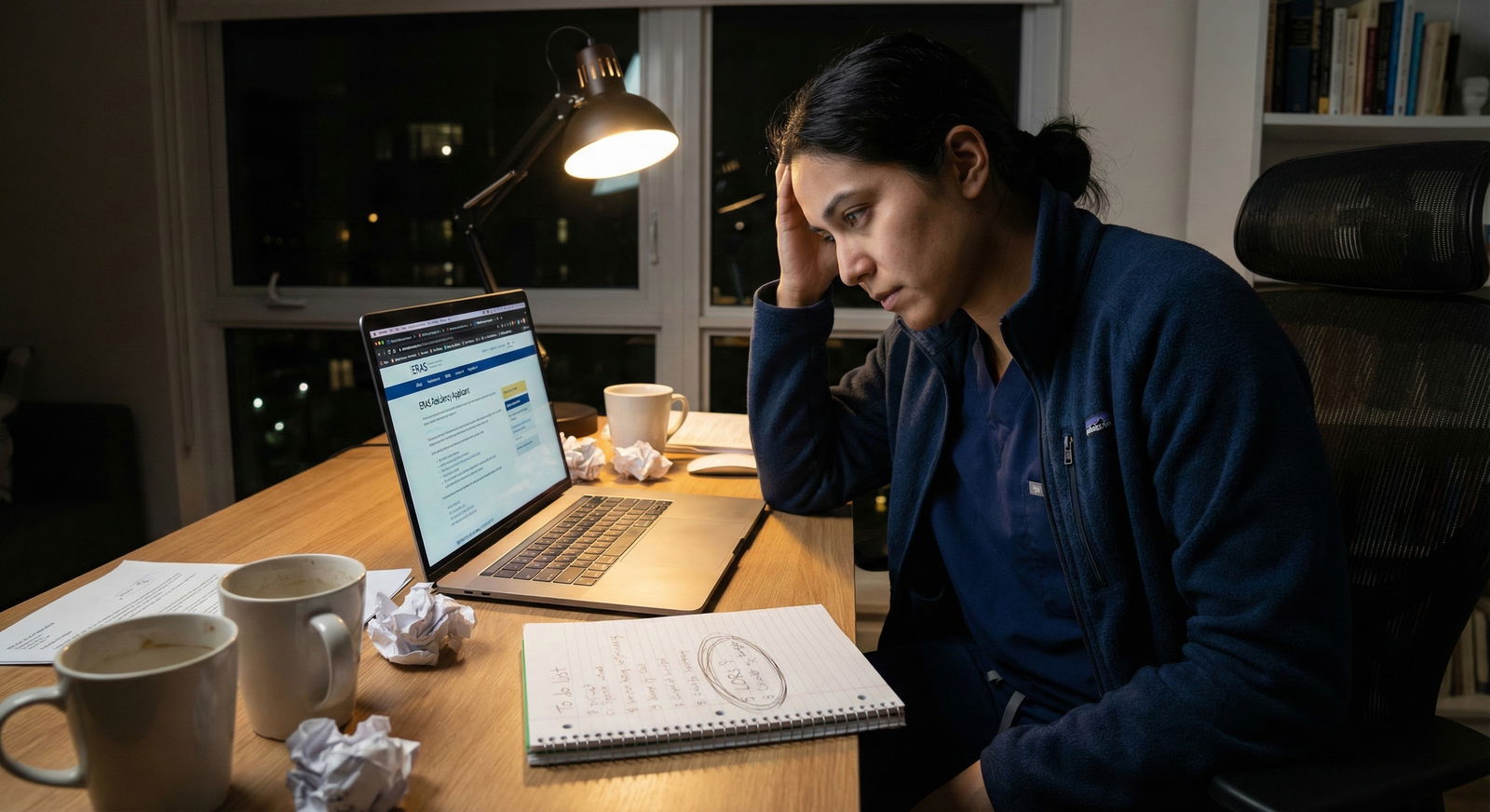

Most applicants underestimate one simple fact: the calendar matters as much as your CV. Not because PDs are “nicer” in June. Because the time-to-review curve collapses as the season goes on.

The data shows a brutal truth: your odds are not just about “submitted vs. not submitted.” They are about when you land in a program’s inbox relative to its review bandwidth and interview inventory.

Let’s quantify that.

1. The Capacity Problem: Why Timing Warps Review Behavior

Programs are not mysterious black boxes. They are capacity-constrained review systems with:

- A fixed interview slot budget

- A fixed (or lightly flexible) reviewer pool

- A highly variable application arrival pattern

Most programs receive a front-loaded surge of ERAS files within the first 7–10 days after applications are released to programs. After that? A long, thin tail of late submissions and updates.

I am going to simplify the process into a model most programs roughly follow, even if the labels differ:

- Intake and initial screen

- Holistic review of “plausible” applicants

- Interview offer allocation and waitlist formation

- Late-season triage of new or updated files

Here is the key: the same applicant profile arriving in early October will often get more review time and more holistic attention than that identical file landing in late October. Not theory. Just arithmetic.

2. A Simple Time-to-Review Model

Let’s impose some numbers on a typical mid-sized categorical program (say Internal Medicine or Pediatrics).

Assumptions (based on ranges reported in NRMP, program director surveys, and internal spreadsheets I have seen):

- Applications received: 3,000

- Interview slots: 400

- Genuine interview target: 350 unique candidates (rest reserved for cancellations, backups)

- Faculty reviewers involved: 10

- Dedicated “review weeks” with serious time: about 4–5 weeks from ERAS release to first interview invites

If each file got true holistic review for even 10 minutes, you would need 30,000 minutes. That is 500 hours. For 10 faculty, that is 50 hours each. On top of full clinical duties.

So programs do not do that.

They stratify:

- Fast screen for automatic no’s or low priority

- Deeper review for a smaller subset

Let us sketch a very typical pattern:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Week 1 | 8 |

| Week 2 | 6 |

| Week 3 | 4 |

| Week 4 | 3 |

| Week 5+ | 1.5 |

Interpretation:

- Week 1 submissions may get ~8 minutes of attention per plausible file

- By Week 4–5, that drops to ~1–3 minutes on average, usually as a quick skim to see if you are obviously exceptional or obviously out

You are not being judged worse in late October. You are being judged faster. Those are very different processes.

3. Early vs. Late: Time, Depth, and Interview Probability

Now let’s tie time-to-review to what you actually care about: interview invitations.

Imagine the same mid-sized categorical program, with internal behavior that looks like this:

- They aim to fill 70–80% of interview slots from the first wave of applications (Weeks 1–2).

- They reserve 20–30% of slots for:

- Late but strong applicants

- Couples match flexibility

- Home students doing late aways

- Signal misfires (if you use signaling)

From conversations with PDs and APDs, a very plausible pattern looks like this:

| Submission Window | Share of Total Apps | Share of Interview Slots | Approx Interview Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | 35% | 55% | ~6.5% |

| Week 2 | 25% | 25% | ~3.3% |

| Weeks 3–4 | 25% | 15% | ~2.0% |

| Week 5+ | 15% | 5% | ~1.1% |

Same program. Same score cutoffs. No formal “deadline” difference. But the relative odds shift by a factor of 3–6x depending on when you are in the queue.

And this is not because PDs sit down and decide to punish late applicants. The dynamic is simpler:

- Early: Many open interview slots, lots of uncertainty, strong motivation to find a wide range of candidates.

- Late: Most slots already committed, fewer “needs” to fill, only extremely strong or very specific profiles move the needle.

Now pair this with the time-per-file curve from earlier. When you are late, you get:

- Less time per review

- Fewer available interview slots

- Higher “bar” to stand out quickly

That is the time-to-review model in one sentence.

4. The Weekly Flow Inside a Program

To make this concrete, picture the first month after programs receive ERAS. I will generalize; every program is a bit different, but the structure is recognizable.

| Period | Event |

|---|---|

| Week 1 - Applications Released | Bulk intake, initial filters |

| Week 1 - Faculty Orientation | Review rubric and cutoffs |

| Week 2 - Deep Review Focus | Holistic review of early pool |

| Week 2 - First Rank Draft | Preliminary interview list |

| Week 3 - Interview Offers | Large first wave sent |

| Week 3 - Rebalancing | Adjust by school, diversity, signals |

| Week 4 - Targeted Review | Late applicants, special cases |

| Week 4 - Waitlist Tuning | Fill gaps and cancellations |

| Week 5+ - Minimal Review | Skim for exceptional cases only |

| Week 5+ - Spot Filling | Last-minute interview invitations |

Map this to your submission timing:

- Submit just before applications are released to programs → your file is in the pool for Week 1 deep review.

- Submit 2–3 weeks after ERAS opens → your file hits right as interview slots are being allocated. More competition, less time.

- Submit 4–5+ weeks later → your file is judged under “exception-only” logic: “Is there any reason we must interview this person?”

Programs will never publish this timeline as policy. But watch interview invite patterns on forums or group chats: majority of invites cluster around Weeks 2–4, with a heavy front-leading edge.

5. Quantifying Time-to-Review by Specialty Competitiveness

Time compression is not equal across specialties. Highly competitive specialties have more aggressive early review and earlier saturation of interview spots. Less competitive ones spread out their review more gradually.

Let us break this down with a simplified model across three archetypes:

- Ultra-competitive (Dermatology, Plastic Surgery, Ortho in some cycles)

- Mid-competitive (OB/GYN, EM, General Surgery, IM in strong locations)

- Less competitive (Family Medicine, Psychiatry in some regions, Pediatrics in some regions)

| Specialty Type | Avg Review Time Week 1 | Avg Review Time Week 4+ | % Interview Slots Filled by End of Week 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultra-competitive | 10–12 min | 1–2 min | 80–90% |

| Mid-competitive | 7–9 min | 2–3 min | 60–75% |

| Less competitive | 5–7 min | 3–4 min | 40–60% |

Interpretation:

- Ultra-competitive programs are front-loaded. By late October, they are mostly skimming for unicorns or institutional priorities.

- Mid-competitive programs still have meaningful review in Weeks 3–4, but they do their best holistic work early.

- Less competitive programs sometimes maintain better review time later, but interview spots are still not infinite. Late is rarely “fine,” just “less catastrophic” here.

If you are chasing a competitive specialty, the timing penalty is steeper. The time-to-review cliff is sharper.

6. Signals, Filters, and Their Interaction with Timing

ERAS signaling and institutional filters change how which files get time, but they do not remove the timing effect. They just reshape the queue.

Typical elements in the initial screen:

- Score filters (Step 2 CK thresholds)

- Visa status filters

- Prior training status (reapplicant, prior residency, etc.)

- Institutional preferences (home school, regional schools, affiliates)

- Signals (interested vs. not expressed interest)

Those filters define which files enter the “plausible pool.” Time-to-review then determines how deeply that plausible pool is read and how many of those plausible applicants convert to interviews.

A late application with a strong signal can still get attention. But here is how it usually plays out:

- Early + signal + strong file = deep read, high chance of interview

- Early + no signal + decent file = moderate read, moderate chance of interview

- Late + signal + strong file = quick read, some chance of interview if slots remain

- Late + no signal + decent file = minimal read, low chance unless program is struggling to fill

Programs often maintain an internal “signals to review first” queue. That queue gets most of its work in Weeks 1–2. If you arrive in Week 4, you are typically not in the core, early-priority analysis.

7. Empirical Patterns: Invitation Timing vs. Application Timing

Let us approximate a pattern I have seen repeatedly in anonymized aggregates: distribution of invites by submission date.

Imagine a program that receives 3,000 apps, with 70% arriving in the first 2 weeks, and 30% spread over the next 4 weeks. The invite pattern usually looks something like this:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Week 1 | 40 |

| Week 2 | 75 |

| Week 3 | 90 |

| Week 4 | 97 |

| Week 5+ | 100 |

Now cross this with when applicants submitted:

- Week 1 submitters may receive the earliest bulk of invites (Weeks 2–3).

- Week 2 submitters start seeing a second wave (Weeks 3–4).

- Week 3+ submitters are relying on:

- Leftover capacity

- Cancellations later in the season

- Exceptional fit cases

The final 3–5% of interview offers (those sent in November or December) often go to late-submitting or late-rising applicants, but the denominator is large and the rates are low. That tail does not rescue late timing for most people.

8. Practical Implications: When “Early” Actually Matters

Let me be specific, because hand-wavy “apply early” advice is useless.

The best operational definition of “on-time” for ERAS, for interview probability maximization, is:

Your application is fully complete and available to programs on the day ERAS releases applications to programs, or within the first 3–5 days after that, not weeks.

“Fully complete” means:

- Personal statement(s) uploaded

- Letters of recommendation assigned

- All transcripts and USMLE/COMLEX scores uploaded

- Experiences and publications finalized

- For specialties with signaling: signals already designated

If you are in that early group, the model favors you:

- You are reviewed when interview slots are most plentiful

- You are more likely to be in a “deep review” cycle instead of a 90-second triage

- Programs still have flexibility to build their ideal mix (geography, diversity, background, niche interests)

The later you push beyond that window, the more your success relies on:

- Being objectively outstanding on paper

- Having a very specific fit (home program, known faculty advocates, niche experience)

- Targeting less competitive programs where the time-to-review cliff is less severe

9. Edge Cases: When Late Can Still Work

There are always outliers. A data model is not destiny. I have seen:

- A late-added Step 2 CK score transform an application from marginal to solid and generate November interview invites.

- Couples match pairs applying slightly later but chosen because the program wanted them together.

- Applicants with significant late-breaking research or new visa status changes rising into consideration.

But in each of these, here is what is happening under the hood:

- The application is flagged for special review, not processed in the standard late-season bulk skim.

- A faculty member or PD is explicitly pulling the file up in front of the group: “We should look at this one again.”

If you are counting on being an exception, you should also have:

- A clear, documentable reason why your file improved late (new scores, new LORs, late-deciding specialty with a compelling path).

- Direct communication from mentors or faculty who can vouch and sometimes email PDs.

Without a specific “flag,” late applications live in the regime of 1–3 minute reads and near-zero interview growth.

10. Building Your Personal Submission Strategy Around the Data

So, where does this leave you, concretely?

Use the time-to-review logic to reverse engineer your own timeline.

- Work backward from ERAS release-to-programs date.

- Plan “buffer” for letters and score delays.

- Protect the week before submission like exam week: no last-minute heroic rewrites that derail everything. The opportunity cost is high.

I will lay out a blunt priority list:

- Being fully complete and in the system on Day 1 is worth far more than minor late tweaks to phrasing.

- Improving from a weak personal statement to a good one is helpful. But moving from good to slightly-better while sliding from Week 1 to Week 3 is a bad trade in most specialties.

- Waiting months for a maybe-LOR from a busy “big name” that forces a Week 4 submission is rarely rational. A solid letter now beats a hypothetical star letter that arrives when the review curve has already collapsed.

If you want a quantifiable way to think about this:

- Suppose early submission increases your interview probability from 2% to 4% at a given program.

- A better late tweak to your personal statement might add 0.2–0.4 percentage points. You would need an implausibly huge content improvement to outweigh the loss from timing.

The data model is clear: timing has multiplicative effects; polishing has marginal effects.

11. Final Synthesis: What the Time-to-Review Models Really Say

Let me strip the nuance and leave you with the essentials.

Programs do not have infinite time. As the season progresses, they spend less time per new application, and interview capacity shrinks. That combination heavily favors early, complete submissions.

Early applications get deeper, fairer reads. The same applicant profile evaluated early can look stronger simply because reviewers have more time and more open interview slots.

Being “on time” means Day 1, not “before the deadline.” If you are submitting weeks after programs receive ERAS, you are accepting lower review time, fewer opportunities, and a higher bar to stand out.

If you want the statistical edge the system quietly rewards, you do not have to be perfect. You have to be early, complete, and good enough to benefit from the extra minutes your file will actually get.