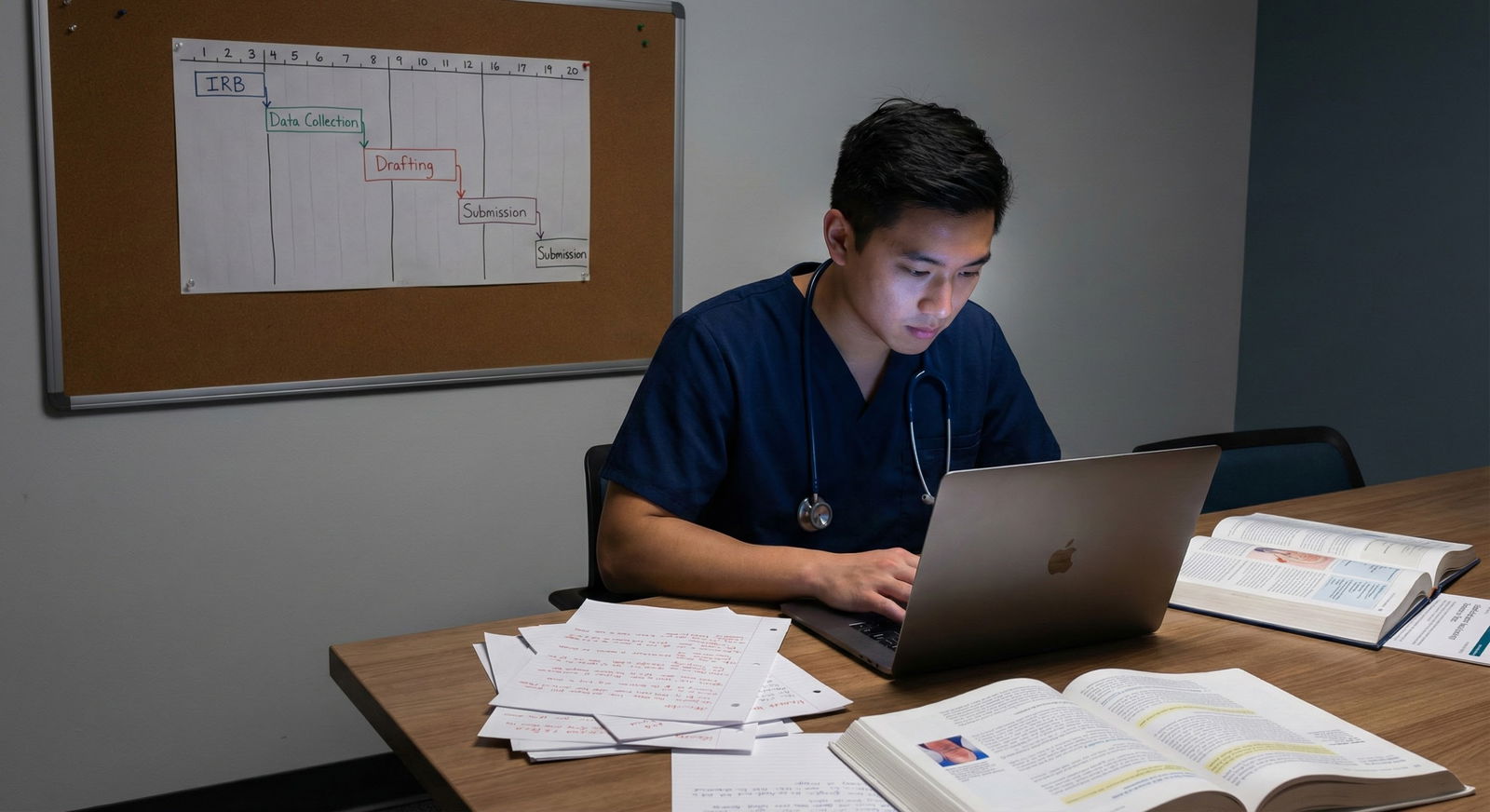

materials during a gap year Resident physician reviewing [teaching portfolio](https://residencyadvisor.com/resources/gap-year-residency/how-to-create-a-g](https://cdn.residencyadvisor.com/images/nbp/resident-physician-reflecting-during-a-non-clinica-8249.png)

Most residents waste their gap year padding their CV; the smart ones use it to quietly become the “teaching person” for their future specialty.

You want to match. You also want a career where you are not just a cog writing notes and clicking boxes. The leverage point that applicants underestimate? A focused, well-documented teaching portfolio aimed directly at the specialty they want.

Let me break this down specifically.

You are in a gap year before residency. Maybe you are doing research, a prelim year that did not roll into categorical, a chief year, or a structured teaching fellowship. Or you are “just working” and reapplying. You can drift through the year doing random tutoring and a few lectures. Or you can engineer a specialty-focused teaching portfolio that makes program directors, clerkship directors, and education committees immediately think: “We can build an educator out of this person.”

I am going to assume you want the second outcome.

1. Get Very Clear On What “Specialty-Focused” Actually Means

“Likes teaching” is cheap. “Demonstrably improves learners in [X specialty]” is currency.

Specialty-focused teaching means three things:

- Your audience is aligned with your target specialty

- Your content is domain-relevant

- Your format and documentation support future academic involvement in that specialty

Let’s make this concrete.

If you want:

- Internal Medicine: Think morning-report style case conferences, EKG sessions, “approach to hyponatremia” workshops, sub-I prep for IM rotations, board-review style questions for M3s.

- Emergency Medicine: Simulation cases (chest pain, sepsis, trauma), airway skills workshops with checklists, “EKG in 10 minutes” series, ultrasound intro sessions.

- Surgery: Anatomy and OR-prep sessions for MS3s, suture lab teaching, pre-op/post-op decision-making workshops, skills checklists, case-based “What would you do next?” boards.

- Pediatrics: Development milestones teaching, vaccine counseling OSCEs, common outpatient complaints workshops, family communication role-plays.

- Psychiatry: Interview-skills workshops, mental status exam teaching, OSCE design for suicidal ideation encounters, psychopharm basic sessions.

Now, match that with the trainee level:

- Pre-clinical students: Conceptual frameworks, diagnostic reasoning, and board-style integration.

- Clinical students: Pattern recognition, plans, notes, sign-outs, common pitfalls on rotations.

- Intern-level: Call-night decision-making, cross-cover triage, “when to wake the attending,” order sets, admit notes.

Your gap-year teaching should clearly answer:

“In this specialty, for this learner group, here is exactly how I have helped people learn and perform better.”

If you cannot answer that in one sentence, you are still in the “random teaching” zone.

2. Understand What a Real Teaching Portfolio Looks Like

A teaching portfolio is not “I did some tutoring and gave two lectures.” That is what people put into ERAS activity descriptions. A portfolio is structured, curated, and reproducible.

At minimum, you want:

- Teaching activities list

Dates, setting, audience, topic, your role, and approximate contact hours. - Sample materials

Slides, handouts, cases, checklists, OSCE station write-ups, question banks, facilitator guides. - Feedback and evaluations

Learner evaluations, peer or faculty observation forms, emails/comments, pre/post data if you have it. - Reflection and growth

A short narrative on what you taught, what did not work, what you changed. This is what sells you as an educator, not a content parrot. - Evidence of impact

Improvement data, course modifications you initiated, adoption by a clerkship/course director, invitations to repeat sessions.

You will not upload the entire portfolio to ERAS. But you will:

- Reference it in your personal statement and experiences

- Offer to send or discuss it in interviews

- Use concrete examples from it in “tell me about a time you taught…” questions

- Leverage it when programs ask about “career goals in medical education”

Think of the portfolio as your internal source document. ERAS and interviews are your distilled highlight reel.

3. Choose a Gap-Year Structure That Maximizes Teaching

You do not need a formal “teaching fellowship,” though that helps. You need access to learners and some control over what you do.

Common setups I have seen work:

Medical Education Fellowship / Chief Resident Year

Gold standard. You get assigned teaching responsibilities, often with faculty mentors. Maximize this by:- Negotiating for sessions specifically in your specialty (IM morning report, EM sim, etc.)

- Asking to join curriculum committees for that specialty

- Designing at least one new session or series, not just inheriting content

Research Gap Year within Your Specialty Department

Many people squander this by sitting at a desk. Better approach:- Volunteer to give recurring teaching for the clerkship tied to that department

- Offer to run board review for the department’s medical student group

- Ask the clerkship director: “What teaching gaps exist for the students on your service, and can I build something to fill one of them?”

Hospitalist / Prelim / Non-categorical Clinical Year

You have less formal academic protection, but more real patients. Strategies:- Run brief 10–15 minute “chalk talks” with students each call shift

- Co-precept with attendings: volunteer to hear student presentations first, then present together

- Ask to be the “student liaison” or to help coordinate teaching schedules

Non-clinical / Industry / Out-of-Hospital Roles

You will have to create your own teaching pipeline:- Volunteer for structured skills labs or pre-clinical small groups at nearby med schools

- Do high-quality, curriculum-style online teaching (but not just random YouTube videos)

- Work with student interest groups in your specialty to run recurring sessions

Your question for every opportunity: “How can I turn this into documented, structured, specialty-relevant teaching?”

4. Design Teaching Activities That Translate Directly into Portfolio Strength

You want activities that:

- Are repeatable (not one-offs)

- Create materials you can save

- Generate feedback

- Are obviously tied to your target specialty

Here is a simple framework that works across specialties:

A. Anchor Series: Your Flagship Teaching Project

During the gap year, build one primary, recurring teaching project. Something you can name in one line.

Examples:

- “Weekly EM Case Conference for M3s rotating in the ED”

- “Sub-I Prep Bootcamp Series for IM-bound 4th years”

- “Surgical Anatomy and OR Skills Lab for MS2s”

- “Psych Interview Skills OSCE Prep for MS3 clerkship students”

Core elements:

- 4–8 sessions over several months

- Each session 45–90 minutes

- Learning objectives clearly written and shared

- A consistent assessment or reflection component

- Anonymous learner feedback each time

You keep:

- The session schedule and descriptions

- Slides, cases, and facilitator notes

- Collected feedback (aggregate, de-identified)

- Any changes you made mid-series based on feedback (this is gold for interviews)

Now you have not “taught a couple of things.” You have led an identifiable curriculum element.

B. Short, High-Yield Recurrent Sessions

On top of the flagship project, layer smaller but frequent contributions:

- 10-minute chalk talks during rounds on classic specialty topics

- Question-of-the-day sessions (e.g., “one EKG at noon” in EM or IM)

- Skills stations in larger workshops (suturing, joint injections, airway, etc.)

Each one gets logged:

- Date, topic, learners, setting

- Quick note on any feedback or improvement

Alone, these are minor. Collectively, they show sustained involvement and growth as a teacher.

5. Document Everything Like an Education Fellow, Not a Random Tutor

This is where most people fail. They teach, but leave no paper trail.

Here is the system I tell people to use:

A. Create a Portfolio Folder Structure on Day 1

Something like:

/Teaching Portfolio – [Your Name]01_CV_&_Summary02_Teaching_Activities_Log03_MaterialsSlidesHandouts_ChecklistsCases_OSCEs

04_Feedback_&_Evaluations05_Project_Descriptions06_Reflection_&_Growth

Maintain a single spreadsheet in 02_Teaching_Activities_Log with:

- Date

- Title of session

- Setting (clerkship, interest group, sim center, online, etc.)

- Specialty alignment (IM, EM, Surgery, etc.)

- Audience level (MS1, MS3, interns)

- Duration

- Format (lecture, small group, simulation, skills lab)

- Evidence collected (evals, pre/post, informal comments)

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Flagship Series | 40 |

| Small Group Sessions | 25 |

| Simulation/Skills Labs | 20 |

| Ad-hoc Chalk Talks | 15 |

By the end of the year, you want that log to show a clear pattern: a large proportion of your teaching lies within your target specialty context.

B. Build Short Project Descriptions as You Go

For each major teaching project (especially your flagship), create a 1–2 page description:

- Background / need (“Students often struggled with X on this rotation…”)

- Goals and objectives

- Session structure and schedule

- Your role (designer vs facilitator vs both)

- Evaluation approach (feedback forms, pre/post questions, etc.)

- Outcomes and planned next steps

This is exactly the type of document that makes education committees take you seriously when you say “I want to do MedEd in [specialty].”

6. Collect and Use Evaluations Intelligently (Without Being Annoying)

This part separates the hobby teacher from the future clerkship director.

You want systematic feedback, not just “students told me they liked it.”

Good options:

- Simple electronic forms (Google Forms, Qualtrics)

- Existing institutional evaluation tools (if your school has them)

- Brief pre/post knowledge or confidence questions built into the session

Aim for:

- 3–5 Likert items about clarity, relevance, engagement, and confidence

- 1–2 free-text prompts (“What was most helpful?” “What could be improved?”)

Then actually:

- Summarize the data in a one-page document per course/series

- Capture 2–3 representative anonymous quotes

- Document at least one specific change you made based on the feedback

Small example:

- Feedback: “Would be helpful to see more examples of real notes.”

- Response: For the next cohort, you add de-identified actual notes to your “approach to chest pain” session and walk through improvements.

- Documentation: This becomes a talking point in interviews about being responsive to learner needs.

7. Make It Explicitly About Your Specialty, Not Just Generic Teaching

Too many people say: “I like teaching and I want to be involved in medical education,” full stop. That sentence has no teeth.

You want to sound like this:

“Given my interest in Emergency Medicine, I have focused my teaching around acute care decision-making for M3s and M4s, including designing a weekly ED case conference that runs during their clerkship.”

Or:

“I am pursuing Internal Medicine with a specific interest in resident education in clinical reasoning. During my gap year I built a structured case-based series for students on our IM floors, with pre/post reasoning assessments.”

Translate your portfolio into that type of language.

To do that, ensure:

- The topics are clearly in your field

- The contexts (ED, wards, OR, psych clinic, etc.) match your specialty

- You can describe how the teaching aligns with actual workflows in that specialty

If you are applying to OB/GYN and your main teaching project is “general physical exam skills for MS1s,” it is better than nothing, but it is not specialty-focused. You either tweak it for prenatal visits, pelvic exams, and prenatal counseling, or you add an OB/GYN-specific project.

8. Translate the Portfolio into ERAS and Your Personal Brand

You will not attach a 50-page PDF to ERAS. But you will mine it for specifics.

A. ERAS Experiences Entries

For your top 1–3 teaching experiences, write entries that:

- Name the scope (“Designed and led an 8-session EM case conference series…”)

- State the audience and size

- Mention evaluation and results (“Mean learner-reported confidence in… increased from 2.6 to 4.1 out of 5…”)

- Tie to the specialty (“Focused on core EM topics including chest pain, abdominal pain, sepsis, and trauma.”)

Avoid vague nonsense like “helped medical students learn clinical skills.”

B. Personal Statement

You do NOT write a generic “I like teaching” paragraph. You:

- Link your clinical motivations in the specialty to your teaching experience

- Give one specific teaching vignette: a session, a learner, or a problem you helped solve

- Show reflection: what you learned about how people learn in your specialty’s environment

Example for EM:

“On our ED clerkship, students repeatedly arrived terrified of managing undifferentiated chest pain. During my gap year, I partnered with our clerkship director to design a recurring case conference, walking them through triage to disposition. Watching their presentations shift from disorganized symptom lists to focused ED problem representation convinced me that my long-term place in Emergency Medicine must include formal roles in medical education.”

C. Interviews

Your portfolio is an answer bank for classic questions:

- “Tell me about a time you taught learners…”

- “What role do you see teaching playing in your career?”

- “Have you ever created curriculum or assessment materials?”

- “How have you handled feedback from learners?”

If you have done the work I am describing, you will not hand-wave. You will say:

- “I designed X. Here is what I saw. Here is the data. Here is how I changed it. Here is what I want to build at your program.”

That is what programs want to hear when they see “interested in medical education” on your application.

9. Build Visible Alignment with Education Leaders in Your Target Specialty

A portfolio sitting in your Google Drive is fine. A portfolio that faculty in your target specialty actually know about is better.

Concrete tactics:

Identify education mentors in the department

Clerkship director, associate program director for education, simulation director, etc.

Ask for a brief meeting with a clear ask: “I would like to focus my gap-year teaching around [specialty] and build something that is actually useful to your learners. Where are the pain points?”Present your work in departmental venues

Department education meetings, resident conference, clerkship orientation.

Even a brief 10-minute “here is the new student series we piloted” talk gets your name associated with “education person” in that department.Co-author education abstracts or papers

You do not need an NEJM trial. A MedEdPORTAL submission, a poster at a specialty education conference, or a local education day abstract is plenty.

Again, anchored in your specialty.Stay in their inbox as a solution, not a burden

Send one concise email mid-year: “Here is a one-page summary of how the student series is going. Any feedback? Would you like me to adjust topics based on what interns have been struggling with recently?”

That is how you become part of their long-term mental map of future educators.

10. Use Online and Asynchronous Teaching Carefully (Quality > Volume)

Everyone wants to start a YouTube channel now. Most of it is undifferentiated noise.

If you go asynchronous, treat it like curriculum, not content dumping.

Better options:

- A structured question bank focused on your specialty, with explanations and references

- Short, case-based blog posts with a reproducible format (vignette → reasoning → key takeaway)

- OSCE checklists, one-pagers, or algorithms for your specialty that your own institution actually uses

You do NOT want to be the person whose “teaching” is 80 low-effort Instagram slides with no evaluation, no structure, and no obvious alignment with your target specialty.

Online components become strong if:

- They are integrated into a live/structured course you run

- You can show metrics (usage, completion rates, feedback)

- Faculty at your institution endorse or use them

Otherwise, keep them as supporting, not central, pieces of your portfolio.

11. Reality Check: Common Mistakes That Wreck Otherwise Good Portfolios

I have watched a painful number of people get this halfway right and then sabotage themselves.

Big mistakes:

Generic, scattered teaching

Tutoring Step 1, random anatomy review, a single MMI workshop, a one-off health fair talk… nothing ties to the specialty. It reads as “I like being helpful,” not “I am building a career in [X].”No documentation

Three months of great teaching and nothing on paper. No log, no slides, no feedback. When you reach ERAS season, it collapses into one vague bullet.No mentor or departmental visibility

You build something quietly in the corner, then expect programs to care. They do not. If your own specialty department barely knows you did this, external programs will not be impressed either.Overstating impact

“Radically improved student performance” with zero data looks bad. Be honest. “Pilot series with positive learner feedback and moderate improvement in pre/post confidence scores” is completely fine.Forgetting that clinical performance still matters more

You will not teach your way out of being a liability clinically. The portfolio is an amplifier, not a shield. Your gap year must not be 100% teaching and 0% maintaining clinical competence (if you are in a clinical role).

12. Snapshot: What a Strong Specialty-Focused Gap-Year Teaching Portfolio Looks Like

Here is how this all might look, distilled.

| Component | Example Content |

|---|---|

| Flagship Project | 8-session ED Case Conference Series for M3 Clerks |

| Additional Teaching | Weekly EKG mini-talks, 4 ED sim sessions |

| Materials | Slide decks, 12 cases, simulation scripts, checklists |

| Evaluations | 60 learner evals, pre/post surveys, summary report |

| Visibility & Output | Presented at ED education meeting, abstract to CORD |

For an IM applicant, or Surgery, or Psych, you substitute appropriately. The structure stays identical.

FAQ (Exactly 5 Questions)

1. Do I need a formal “teaching title” (like Chief Resident or Teaching Fellow) for this to matter?

No. Titles help open doors to learners, but programs care far more about what you actually did and can describe. I have seen unmatched applicants without any formal title build stronger, more focused teaching portfolios than some chiefs who coasted on the position. If you lack a title, compensate with specificity, documentation, and alignment with your target specialty.

2. How many hours of teaching do I need in my gap year to make this convincing?

There is no magic number, but as a rough floor, I start taking it seriously when I see something like: one flagship project (4–8 sessions), plus ongoing smaller teaching adding up to at least 30–40 contact hours over the year. Some will do much more. What matters is not the raw hour count but the coherence: does it look like a deliberate, specialty-focused effort instead of scattered volunteering?

3. What if my home institution does not have strong infrastructure for medical education?

Then you build small and local first, and you get creative. Partner with student interest groups, contact the nearest med school even if it is not your alma mater, use simulation centers if available, or do highly structured online teaching tied to a clear curriculum. Even a tightly run 4-session specialty-specific workshop, properly documented and evaluated, is more valuable than a year of aimless “helping out.”

4. How do I avoid annoying students or faculty by constantly asking for evaluations?

You do it sparingly and predictably. For recurring series, collect evaluations at the end of each cohort, not every single session. Use brief forms that take 2 minutes to complete. Coordinate with clerkship or course directors so your evaluations align with what they already use. And be transparent: tell learners you are trying to improve the sessions and that their feedback actually changes what you do next time.

5. Will a strong teaching portfolio compensate for a weaker Step score or prior failure to match?

It will not magically erase big red flags, but it can change the story you are telling. Instead of looking like someone drifting in a gap year, you become someone clearly building toward an academic career in that specialty. That impresses many program directors, especially at institutions that value education. Combined with evidence of improved board performance and solid clinical letters, a focused teaching portfolio can be one of the differentiators that finally gets you in the door.

If you remember nothing else:

First, anchor your gap year teaching inside your target specialty and learner level. Second, treat every teaching activity as curriculum—planned, documented, evaluated, and refined. Third, make sure education leaders in that specialty know who you are and what you built. That is how a “gap year” turns into the year you quietly became an educator your future program actually wants.