The way most people use a research gap year before residency is wasteful.

They treat it like “time to do research” instead of “12 months to build a manuscript pipeline that actually produces submissions before ERAS locks.” Those are not the same thing. One gets you a few abstract lines and a weak “in progress” section. The other can change how program directors read your application.

Let me walk you through the second one.

The Real Constraint: ERAS, Not the Calendar

Your “12‑month” manuscript pipeline is not a true 12 months.

If you are applying in the regular cycle:

- ERAS opens: early June

- Programs can start reviewing: late September

- Rank lists / interviews depend heavily on what is visible by September

So if your gap year is, say, June to next May, your effective timeline for things that matter to your application is:

- From: Month 1 of gap year

- To: Month 4–5 for accepted abstracts

- To: Month 8–9 for submitted manuscripts

- With publications often appearing after you have already applied

That means the game is:

- Stack submissions and acceptances before September.

- Have a credible pipeline of “submitted” / “under review” work by ERAS.

- Have at least a few things accepted online‑ahead‑of‑print or in press.

You are not promising to cure cancer in 12 months. You are building a visible, believable publishing machine.

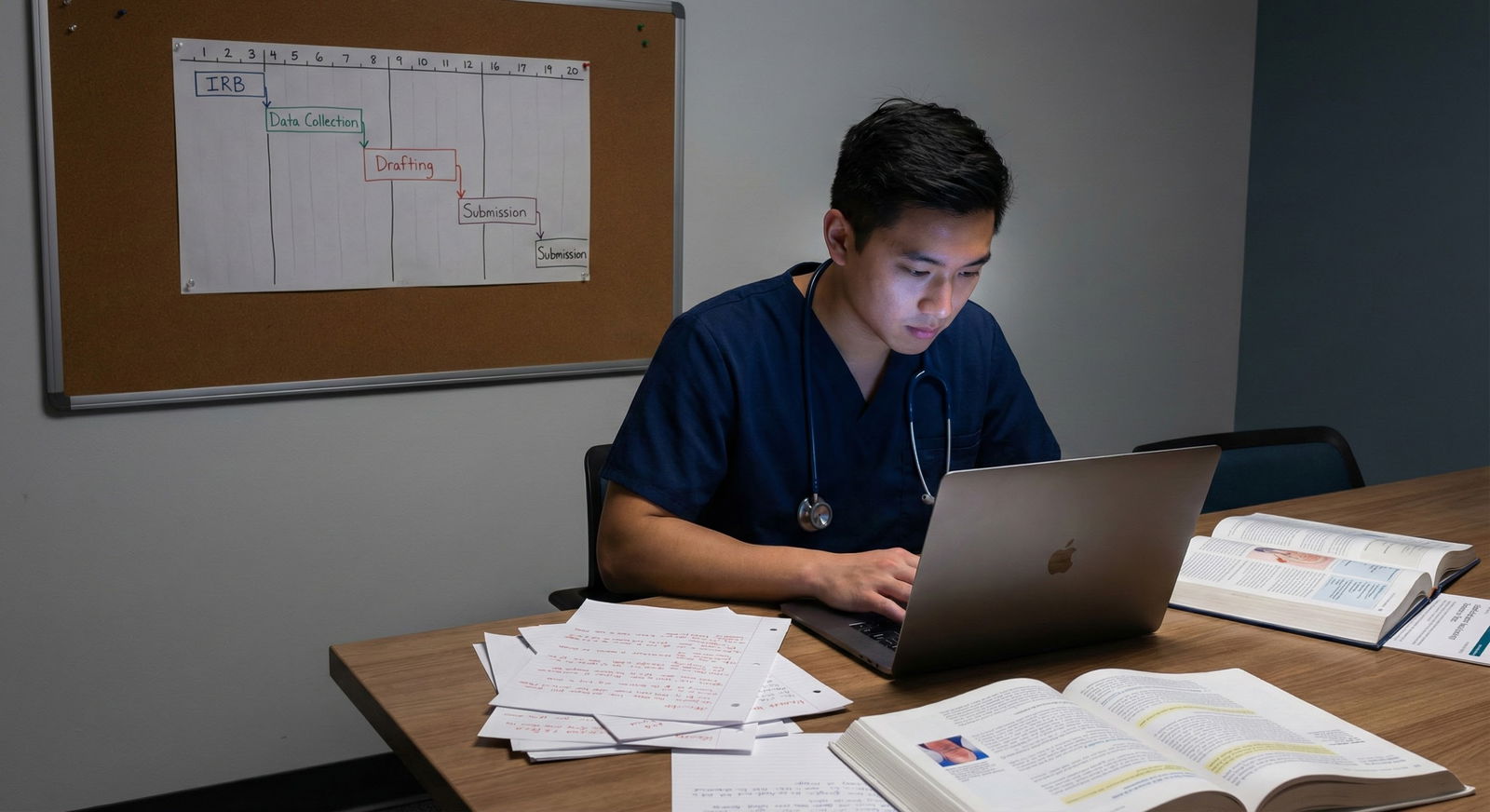

The 12‑Month Map: IRB to Submission

Here is the basic high‑yield pipeline if you are starting the gap year with little or no ongoing work.

| Task | Details |

|---|---|

| Setup: Join Research Group & Topics | a1, 2025-06, 4w |

| Setup: IRB Prep & Submission | a2, 2025-06, 6w |

| Data Projects: Retrospective Project 1 Data | b1, 2025-07, 8w |

| Data Projects: Retrospective Project 2 Data | b2, 2025-09, 8w |

| Writing: Manuscript 1 Draft & Rev | c1, 2025-09, 8w |

| Writing: Manuscript 2 Draft & Rev | c2, 2025-11, 8w |

| Writing: Case Reports / Briefs | c3, 2025-07, 10w |

| Submission: Manuscript 1 Submission | d1, 2025-11, 2w |

| Submission: Manuscript 2 Submission | d2, 2026-01, 2w |

| Application: Abstracts & Posters | e1, 2025-08, 10w |

| Application: Prepare ERAS CV | e2, 2026-02, 4w |

Notice something: IRB runs in parallel with smaller projects. You never sit idle “waiting for IRB.”

Step 1: Choose the Right Projects for a Gap Year

You do not have time for a prospective RCT from scratch. If your mentor suggests this as your primary gap‑year project, they are not thinking about your match.

You want projects that:

- Are feasible within 3–6 months from first dataset to first submission.

- Can be run in parallel.

- Are in the field you want to match into (or at least adjacent).

- Have predictable IRB paths.

The usual gap‑year workhorses:

- Retrospective chart reviews (classic, high yield).

- Database studies (institutional or national).

- Case series and single‑case reports.

- Secondary analyses of existing datasets in the lab.

- Narrative or systematic reviews / meta‑analyses (if you have guidance).

What you avoid as your primary deliverable:

- Complex prospective trials.

- Basic science with experiments that rely on multiple other people’s schedules and equipment.

- Anything that needs rare event accrual over long time periods.

You can still participate in those as a secondary trainee, but your core manuscript pipeline must be built on projects you can personally push to submission on a calendar, not on vibes.

Step 2: Lock Down Mentors and Authorship Early

This is where people get burned. They “help with a project” all year and discover in July that their name is somewhere in the middle and the paper is moving at attending‑speed (glacial).

You need:

- One primary research mentor who actually publishes.

- A clear understanding of:

- Which projects you are first author on.

- Which you are middle author on.

- Decision authority: who can say “we are submitting this draft by X date.”

Have this conversation explicitly:

“I have a one‑year gap before residency and need at least two first‑author submissions before ERAS. What projects can I own end‑to‑end if I put in the work?”

If they hesitate or stay vague, look for another group, or split your time. Harsh, but accurate.

You should aim, for a single serious gap year, for something like this mix:

| Output Type | Target Number | Authorship Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Full manuscripts | 2–3 | 1–2 first author |

| Case reports/briefs | 2–4 | 1–3 first author |

| Abstracts/posters | 3–6 | Mixed |

| Reviews/meta-analyses | 0–1 | Variable |

You will not hit all of that perfectly, but this is what a well‑run gap year can reasonably generate.

Step 3: IRB – Do Not Let It Eat 3 Months

IRB delays are the excuse of people who did not plan. Yes, some IRBs are slow. But most of the time the bottleneck is your team.

For a retrospective chart review or database study:

Define a tight, clear question.

“All patients with sepsis” is weak and unfocused.

“Predictors of ICU transfer among ED patients with suspected sepsis and normal lactate” is better.Write a protocol that matches what your IRB sees all the time.

Ask your mentor or admin for a successful previous template from the same department and adapt it ruthlessly. Do not reinvent their format.Pre‑decide:

- Inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Primary and secondary outcomes

- Sample size target and time window

- Data variables and how they are defined (e.g., hypotension by SBP < 90 or requiring vasopressors)

Submit a clean, internally consistent application with:

- No obvious missing sections

- Clear data security plan

- Realistic risk/benefit language

Your goal: IRB submitted within the first 4–6 weeks of the gap year. Not “we are talking about the project” for 3 months.

While IRB is in review:

- Work on case reports (often exempt or not human subjects).

- Start a narrative review in the same topic area to strengthen your background knowledge.

- Learn the statistical tools you will need (R, Stata, SPSS, or at least how to talk to a statistician intelligently).

Step 4: Parallel Tracks – Big Manuscripts and Small Wins

You cannot just have “the big project.” Manuscripts take time, senior authors get busy, reviewers delay.

You need multiple tracks running:

- Major retrospective project #1 – your flagship.

- Secondary retrospective/database project – maybe as second author.

- 2–3 case reports or a small case series.

- One review article (preferably invited, but fine if trainee‑initiated under good mentorship).

A rough 12‑month pipeline with overlapping work:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Major Retrospective Projects | 40 |

| Secondary Projects | 20 |

| Case Reports | 15 |

| Reviews/Meta-analyses | 10 |

| Admin/IRB/Meetings | 15 |

The trick is sequencing:

- Case reports move fastest: identify, collect, write, submit. Cycle time can be 4–8 weeks.

- Reviews sit in the middle: 2–3 months if well scoped.

- Retrospective projects: 4–6 months from IRB approval to submission if you push.

You want early small wins (case report accepted, abstract accepted) by Month 3–5. That morale boost matters, and it populates your ERAS “Accepted” line.

Step 5: Data – Extraction, Cleaning, and Not Drowning in Excel

This is where trainees either become indispensable or become dead weight.

For retrospective clinical projects:

Build a real data dictionary before you pull data.

Variable name, definition, how it is stored, coding scheme (e.g., 0/1, text), units, timepoint. Write it down.Decide on your data capture tool:

- REDCap (ideal)

- Institutional data warehouse outputs into CSV

- Excel/Google Sheets (acceptable but dangerous if sloppy)

Extract in layers:

- First pull: broad, possibly messy, overinclusive.

- Cleaning: remove duplicates, verify key identifiers, check for obviously impossible values.

- Apply inclusion/exclusion criteria systematically.

Document every decision.

“Excluded 27 patients with missing outcome data” is fine if you can reproduce it and explain it.

You do not have to be a biostatistician, but you must be the person who knows the dataset better than anyone else in the project.

And you must avoid the fatal error: starting analysis before the data is clean and final. Re-running stats three times because your dataset keeps changing wastes months.

Step 6: Writing for Speed: Templates, Not Art

You are not writing a novel. You are building reproducible text.

The fastest trainees I have worked with follow a strict order:

Tables and figures first.

They clarify your story. Table 1 (baseline characteristics), Table 2 (main outcomes), key figure if appropriate.Results section second.

Describe exactly what the tables show. No interpretation, just numbers. Use parallel structure so you are not reinventing phrasing every time.Methods third.

Heavily templated from the protocol and IRB. Same sequence:- Study design

- Setting

- Participants

- Variables

- Data sources/measurement

- Bias

- Study size

- Statistical methods

Introduction and Discussion last.

After you know exactly what your results are and how strong/weak they look.

You should also have your own reusable “manuscript skeleton” documents by Month 2:

- Standard phrases for retrospective design.

- Standard phrases for limitations (single center, retrospective, etc.).

- Standard conflict of interest, author contributions, and funding language.

If you write each paper from a blank page, you will not hit 2–3 submissions in a year. Use your own templates, edit them ruthlessly, and adapt to journal style.

Step 7: Journal Strategy – Where You Submit Matters for Timing

Sending your flagship paper to the highest IF journal on Earth and waiting six months for a rejection is a bad gap‑year move. That game is for people with multi‑year timelines.

You choose journals based on:

- Match to your topic and study design.

- Reasonable turnaround time (you can often see this on journal websites or by asking people in your group).

- Acceptance rate that is not fantasy‑level low.

A pragmatic sequencing approach:

Aim at a solid, field‑relevant journal as first choice.

Not JAMA. Not NEJM. Something respectable for your specialty.If rejected without review or after first review: pivot fast.

Adjust format and references and submit to the next journal within 1–2 weeks, not 2 months.For case reports, consider:

- Dedicated case report journals (fast, but lower prestige).

- Specialty journals that still publish case reports or brief communications.

You are optimizing for:

- Submissions logged on ERAS (clear evidence of productivity).

- At least a few acceptances in journals that people have heard of, not predatory outlets.

Keep a living document with:

- Journal name

- Scope

- Word limits

- Formatting quirks

- Typical timeline

This way you are never spending two weeks just figuring out where to send something.

Step 8: Aligning With the ERAS Calendar

Let us anchor this to a real timeline. Say your gap year runs June to next May and you are applying in the next ERAS cycle.

Key milestones that actually matter to applications:

June–July (Months 1–2):

- Join a research group.

- Lock 2–3 main projects with authorship roles defined.

- Submit at least one IRB.

- Start 1–2 case reports.

August–October (Months 3–5):

- IRB approvals coming in.

- Data extraction started.

- One case report submitted.

- Abstracts submitted to relevant conferences (important for ERAS entries).

November–January (Months 6–8):

- First major manuscript drafted and in internal revision.

- Second retrospective project well into data collection.

- Another 1–2 case reports/briefs written.

February–April (Months 9–11):

- First major manuscript submitted to a journal.

- Second major manuscript near submission.

- At least 3–5 total submissions (full papers + case reports).

May–June (Months 12+):

- Preparing ERAS: update CV with “accepted,” “in press,” and “submitted” statuses.

- Email mentors for strong letters emphasizing your research productivity and independence.

By the time programs see your ERAS:

- You want several lines that say “Published” or “Accepted.”

- You want several more that say “Submitted” or “Under Review.”

- Your experiences section should have a coherent narrative: you led specific projects, not just “assisted with research.”

Step 9: Making the Work Legible to Program Directors

Raw numbers of pubs are not enough. They want to know:

- Does this person finish things?

- Are they the kind of trainee who takes ownership?

- Do they understand the field they claim to love?

You make your gap‑year pipeline legible in three places:

ERAS Publications section

- First‑author work is gold.

- Have correct citations. No “submitted” listed as “accepted.” That gets noticed.

- Group things in the same topic so it looks like focus, not random noise.

Experiences section

Instead of: “Research assistant – helped with data collection.”

Better: “Led retrospective cohort study on X; drafted manuscript; coordinated revisions with co‑authors; submitted to [Journal].”Personal statement / interviews

Talk like someone who knows their project at a deep level:- Specific numbers.

- Specific challenges you solved.

- Concrete next steps or spin‑off questions.

The subtext you want to send: “If you give me a year or two in your residency, I will produce similar output for your program.”

Step 10: Common Failure Patterns (And How to Avoid Them)

I see the same mistakes over and over:

Overcommitting to 8–10 projects.

Result: no single first‑author manuscript finished. Your name is lost in the middle of 2–3 big multi‑author efforts.

Fix: Prioritize 2–3 projects where you are first or second author. Say “no” to some “cool ideas.”Waiting for mentors to move.

Drafts sit in inboxes for weeks. You do nothing.

Fix: Polite but persistent follow‑up. Offer concrete help. “I can incorporate the reviewer comments and send you a clean version to approve.”Getting lost in perfectionism.

People tweak intros for weeks, scared to submit.

Fix: Hit journal guidelines, ensure scientific honesty, then submit. Peer review exists for a reason.Ignoring stats until the end.

You pull tons of data then discover your analysis plan is flawed or underpowered.

Fix: Talk to a statistician early. Even a 30‑minute consult can save you months.Working in isolation.

No other gap‑year students to calibrate with, no writing group, no feedback.

Fix: Build a small peer circle. Share timelines, hold each other accountable.

Putting It All Together: A Sample 12‑Month Manuscript Portfolio

If you execute this with discipline, a realistic output by the time ERAS goes live might look like:

- 1–2 first‑author retrospective manuscripts:

- Status: 1 submitted, 1 under internal revision or just submitted.

- 1 second‑author manuscript:

- Status: submitted or in revision after first review.

- 2–3 case reports/briefs:

- Status: 1 accepted or in press, 1–2 submitted.

- 2–4 abstracts:

- Status: accepted or submitted to national/regional meetings.

- 1 narrative review:

- Status: accepted, in press, or submitted.

Not fantasy. I have seen multiple motivated gap‑year students hit or exceed this, especially in medicine, neurology, EM, anesthesia, and surgical subspecialties with strong research infrastructure.

And when you sit in interviews, you do not just say “I did research.” You say:

- “We analyzed 460 patients with X…”

- “Our main result was A; that has implications for B…”

- “I led the data extraction and wrote the first draft, and after two rounds of revision, we submitted to [Journal] in March.”

That sounds like someone ready for an academic residency. Because it is.

FAQ (Exactly 4 Questions)

1. What if my IRB takes 3–4 months and I lose half my gap year?

Then you over‑indexed on one project. You never rely on a single IRB‑dependent project. You should have parallel tracks that are IRB‑exempt or use existing, already‑approved data: case reports, a review article, helping with someone else’s ongoing retrospective project. If your main IRB is slow, you pivot time into the projects you can move now, instead of waiting passively.

2. Do “submitted” or “in progress” manuscripts actually help for residency applications?

Yes, when they are credible. Program directors are not stupid; they know the difference between padding and a coherent pipeline. A couple of well‑described, first‑author “submitted” manuscripts with clear roles and strong letters backing that story are far more persuasive than a long list of vague “in preparation” items. But you still want at least a few accepted or in‑press works to prove that you can close the loop.

3. How do I choose between doing a big prospective project vs. multiple smaller retrospective ones?

In a one‑year gap before residency, you almost always favor multiple smaller retrospective and secondary projects. A big prospective project can be worthwhile if you are joining a trial that is already enrolling and your role is well defined, but it should not be your only bet. For the match, finished work beats grand but incomplete efforts every time. Two solid retrospective papers and a few case reports will do more for your ERAS than an unfinished prospective trial.

4. How many hours per week should I realistically devote to this to hit 2–3 submissions?

If you treat the gap year like a full‑time job—40 to 50 hours per week—you can comfortably drive 2–3 manuscripts to submission plus side projects. If you are splitting time with moonlighting, tutoring, or clinical work, you need to be more ruthless with project selection and timelines. Below 20 focused research hours per week, hitting multiple first‑author submissions in a year becomes unlikely unless you join projects already well underway. The pipeline I described assumes you are treating research as your main job, not a hobby.

With a deliberate 12‑month pipeline, you stop “doing some research” and start behaving like junior faculty in training. That mindset shift alone changes how mentors invest in you and how programs read your application. Once you have that machine running, the next question is how to leverage those projects into strong, specific letters and a compelling academic narrative on ERAS. But that is a discussion for a different day.