Most residents waste conferences collecting tote bags instead of mentors. That is a strategic error.

If you are in a gap year before residency and serious about the Match, conferences are not “optional extras.” They are your single best density of future letter writers, phone-call-makers, and behind-the-scenes advocates you will ever stand in a room with.

Let me break this down specifically: you are not going to a conference to “network.” You are going to engineer 3–5 long-term mentorship relationships that will still matter when you are an attending.

1. Get Ruthlessly Clear On Your Targets Before You Book Anything

You cannot “conference network” effectively if your goals are mush. Vague intent leads to vague conversations and zero follow‑through.

You need three concrete decisions up front:

- What you want from the next 1–3 years

- What you want from the next 10 years

- Where conferences can realistically move the needle

Decide your near-term and long-term plays

Near-term (gap year + match cycle) goals might include:

- Get on a multi-center project that will still be producing abstracts during residency interview season

- Secure at least one strong, specialty-relevant letter writer who knows you beyond your CV

- Become “the known student” to a small cluster of attendings at 3–5 target programs

Long-term (5–10 years) goals might be:

- Break into a highly network-driven subspecialty (interventional cardiology, peds heme/onc, MICU, etc.)

- Position yourself for a specific fellowship at a well-known institution

- Build a career niche (quality improvement, medical education, informatics, global health) with a recognizable mentor in that space

Those answers determine which conference matters.

Choose the right conferences, not the fanciest

The mistake I see repeatedly: students blow their entire travel budget on the biggest-name national meeting, stand in a ballroom with 12,000 people, and expect magic.

You want conferences where:

- Your gap year status is an asset, not an afterthought

- Faculty actually attend posters and small-group sessions

- Trainees can realistically get facetime with leaders (not just watch them on a stage)

For a gap year before residency, priority order usually looks like this:

- Specialty national meeting (e.g., ATS, AHA, ASCO, APA, RSNA)

- Subspecialty/smaller focused meetings (e.g., CHEST, Pediatric Academic Societies, SGIM, SCCM)

- Regional/state society meetings connected to your target programs

- Niche meetings relevant to your “hook” (e.g., AAMC GEA for med ed, AMIA for informatics, SGIM QI tracks)

If you are undecided between conferences, use this framework:

| Priority | Factor | Target Level |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Programs you care about | 5–10 present |

| 2 | Access to faculty | Small/medium size |

| 3 | Student/trainee programming | Explicitly present |

| 4 | Poster/discussion density | High in your area |

| 5 | Travel cost/logistics | Reasonable |

If a meeting has no visible trainee programming, minimal poster time, and celebrity plenaries only, it is not your primary networking conference.

Treat this like an exam: pre‑conference study

You would not walk into Step 2 CK cold. Do not walk into a conference cold either.

Before you go, build three lists:

Must-meet (5–8 names):

- Program directors at top 3–5 target programs

- People publishing repeatedly in your sub-niche

- Anyone your current mentor says, “If you can get in front of Dr. X, do it”

Nice-to-meet (10–20 names):

- Associate PDs, fellowship directors

- Mid-career faculty known for working with trainees

- Senior fellows whose work overlaps with yours

Safety contacts (10–20 names):

- Faculty or fellows at places where you could credibly match, even if not your “dream”

- Alumni from your medical school now in residency/fellowship

- Residents who consistently present / moderate sessions at your target programs

You are not “hoping to meet someone.” You are hunting a specific list.

2. Engineer Mentorship Before You Ever Step On the Plane

If you only start introducing yourself once you arrive, you are late. Pre‑conference contact is your unfair advantage.

How to write pre‑conference emails that get answered

Faculty are busy. They will ignore lazy, generic outreach. But gap-year trainees with focused asks and evidence of real engagement do get replies.

The structure that works:

Subject line options:

- “Prospective [specialty] applicant – would value 10 min at [ConferenceName]”

- “Following your work on [specific topic] – quick intro at [ConferenceName]?”

- “[Med student / gap year trainee] with abstract in [session name] – mentorship question”

Email body (tight, 5–7 sentences):

- One line: who you are (gap year status, med school, specialty interest)

- One line: how you know them (specific paper, talk, or role – not “I saw your name on Google Scholar”)

- Two lines: your current work + 1–2 year goal (e.g., matching in pulm/crit with focus on ARDS outcomes)

- One line: specific ask for 10–15 minutes at the conference

- Offer 2–3 time/location possibilities (poster hall during X, after Y session, early morning coffee)

- One-line close: gratitude + flexibility

Do not attach your CV on the first email. That smells like work for them. If they reply, you can send it when they ask or just bring a concise one-page version printed.

Use your current mentors as force multipliers

The highest-yield email you never send is the one your mentor sends for you.

Ask clearly:

“Dr. Patel, I saw Dr. X (Cleveland Clinic) and Dr. Y (UCSF) will be at ATS. Would you be willing to send a quick connecting email? I am trying to explore ARDS clinical research opportunities during my gap year and would value their perspective.”

Mentors who are even mildly invested in you will often do this. Their 3‑line email dramatically raises the chance that Dr. X actually shows up at the poster session you mentioned.

Map your conference days like a surgical schedule

Do not treat the program app as a random menu. Build an actual schedule:

- Anchor events: your own presentation(s), your mentor’s sessions, program director panels

- Targeted sessions: where your must-meet people will predictably be (they are often speaking, moderating, or listed as discussants)

- Open blocks: 30–45 minute windows marked for “hallway conversations” and “poster wandering”

This is where people fail: they pack every time slot with talks, then they “don’t have time” to talk to the person they flew across the country to meet.

You are not there primarily for didactics. You can read the slides later. You are there for human beings.

3. How To Actually Talk To People Without Sounding Like A Robot

Networking advice online is mostly written by people who have never begged for a letter in their lives. Let’s fix that.

Your script for approaching a faculty member cold

Scenario 1: After a talk

- Wait until the immediate crowd clears a bit

- Step up, name badge visible, no phone in hand

“Dr. Lee, I am Alex Kim, a gap year trainee from [Institution]. I have been reading your work on [specific topic]—your paper on [very short reference] actually shaped a project I am doing now. I am planning to apply into [specialty] and would value one quick question if you have a minute.”

Then ask a focused question that signals you know your stuff:

- “If you were starting in this field right now with a gap year, where would you plug in to get meaningful research experience?”

- “For someone aiming at a clinician-educator path in [specialty], who are the best people to learn from at early stages?”

Do not pitch yourself in detail yet. Your goal here is to make a good impression and open the door to a longer conversation later in the conference (or after).

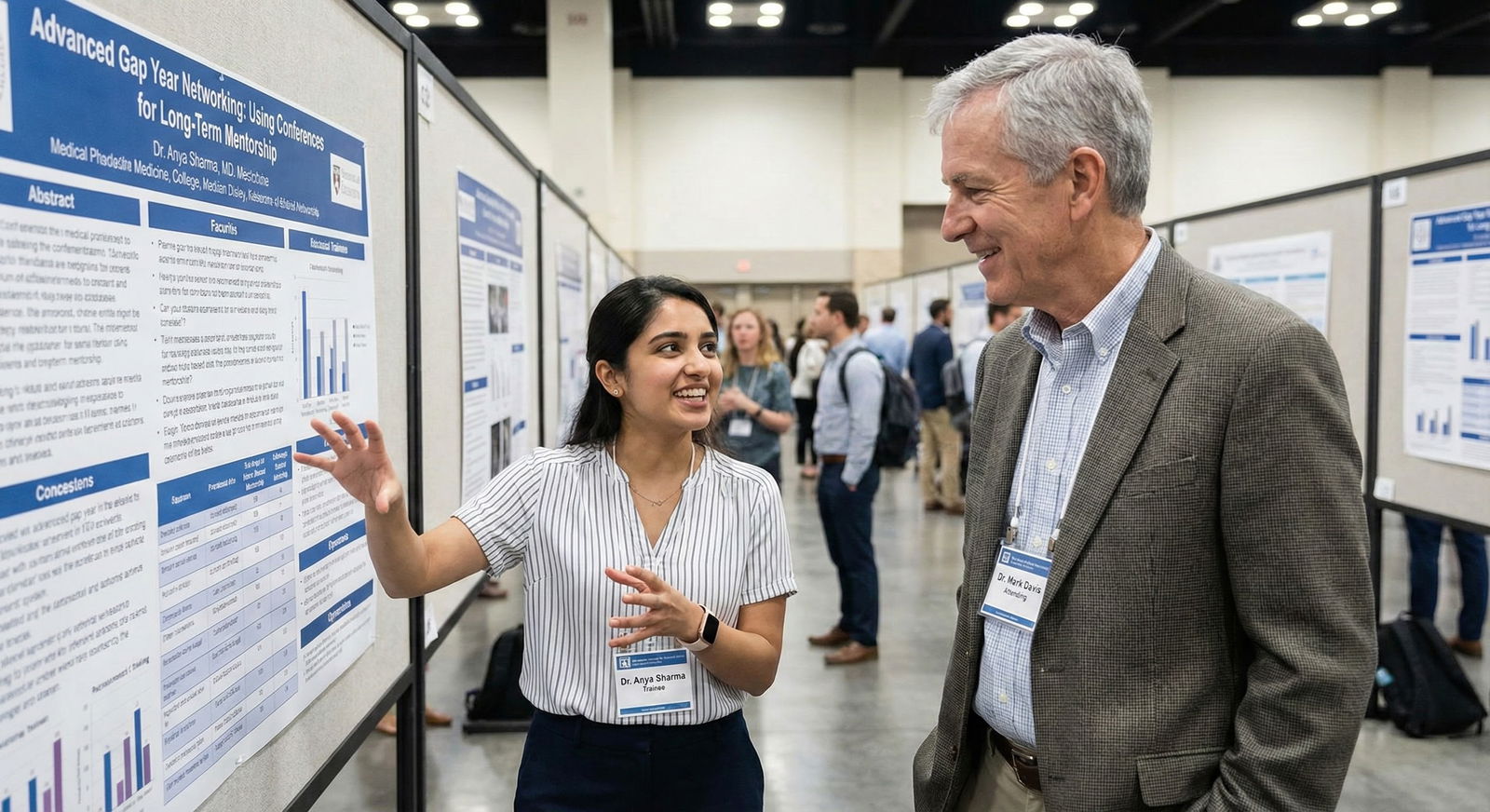

Scenario 2: Poster sessions

Poster sessions are where the real networking happens, because everyone is standing around feeling slightly awkward.

You see Dr. X (your must-meet) alone, skimming posters. You walk up.

“Hi Dr. X, I am [Name], in a research year at [Institution]. I have been following your group’s work on [something concrete]. Do you have a minute to hear about a related question I am working through?”

Then you tie your work to theirs in 1–2 sentences, max. This is not your thesis defense. It is a hook.

What to say about your gap year without sounding defensive

Residents and attendings will ask: “So you are in a gap year—what are you doing now?”

If you answer with a vague “some research” or “taking time to figure things out,” you are wasting ammunition.

Use a 3‑part structure:

- What you are doing

- Why you chose it strategically

- Where you want it to lead

Example:

“I am in a dedicated research year in pulmonary/critical care at [Institution], working with Dr. Patel on ARDS outcomes using our ICU database. I wanted a year to build real research skills and get deeper into this field before applying. The goal is to match into a residency where I can keep doing outcomes research with strong critical care mentorship.”

That answer sounds intentional. Purposeful. Like someone a mentor might invest in.

Avoid the two most common conversational mistakes

Mistake 1: The CV monologue

The student talks uninterrupted for 4 minutes about their projects, leadership roles, and why they love the specialty. The faculty glazes over, nods politely, escapes.

Your rule: never talk about yourself for more than 20–30 seconds without handing the conversational ball back.

Mistake 2: The dead‑end compliment

“You are such an inspiration. I really enjoyed your talk.” Then silence.

You have given them nothing to work with. Always follow a compliment with either:

- A question about their path or current work

- A brief connection to your own specific interests

4. From Nice Conversation To Actual Mentorship

This is where most trainees fall apart. They have five decent chats, collect business cards, add people on LinkedIn, then… nothing.

A conversation is not mentorship. Mentorship is built through repeated, structured, mutually respectful contact that actually goes somewhere.

Identify who is worth pursuing

At the conference, pay attention to three things:

- Who actually seems to like working with trainees?

- Who asks you questions about your goals, not just about your current project?

- Who hints at concrete next steps? (“We have a registry you might be interested in,” “We are always looking for motivated students”)

Out of 15 people you talk to, maybe 3–5 will fall in this bucket. Those are the ones you follow up aggressively (but professionally) with.

The 48‑hour follow‑up rule

Within 48 hours of the interaction (ideally while you are still at the conference or on the plane home), send a short follow‑up email.

Do not wait a week. By then, they have forgotten your face.

Template:

- Subject: “Great to meet at [Conference] – [very short reminder of context]”

- 1 line: Thank them for their time, mention the specific context (“after your ICU outcomes session,” “during the poster walk‑through”)

- 2–3 lines: Reflect back one specific piece of advice or point they made and how you plan to act on it

- 1–2 lines: Make a small, concrete ask if appropriate:

- “Would you be open to a brief Zoom in the next few weeks so I can ask a bit more about how you approached X early in your career?”

- “If your group ever has need for remote data help / literature synthesis, I would be eager to contribute during my gap year”

Attach your CV this time, with a sentence: “I am attaching a one‑page CV for context, in case helpful.”

Convert “nice senior person” into “actual mentor”

Mentorship has stages. At a minimum, you want them to move through:

- Recognize your name and face

- Know your short- and medium-term goals

- See you execute on at least one thing you said you would do

- Have a stake in your trajectory (because they have invested time or attached their name to a project with you)

Practically, this means:

- Schedule a 20–30 minute Zoom within 4–6 weeks of the conference. Prepare 3–4 specific questions, not “tell me your life story.”

- Ask explicitly for advice on concrete decisions: “I have offers to continue work at [current institution] versus join a multi-center project at [other site]. How would you think about that tradeoff?”

- Offer to help with something realistic: data cleaning, lit review, quality project. Do not overpromise; nothing poisons mentorship faster than flakiness.

Over time, your email cadence might be:

- Brief update every 2–3 months (progress, questions, specific thanks)

- Occasional asks that are worth their time (informational intro to another faculty, feedback on a personal statement paragraph, opinion on program tiers)

5. Using Conferences To Build A Long-Term Mentorship Network

One mentor is unstable. People move. They burn out. They change roles. You want a small lattice of mentors, each filling a specific function.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Career Strategy | 25 |

| Research | 35 |

| Program-Specific | 20 |

| Peer/Near-Peer | 20 |

Know your mentor “types”

You should be consciously looking for:

- Strategy mentor: usually senior or mid-career, big-picture advice on specialty, fellowships, and how the game is actually played

- Research mentor: the person who gives you real authorship opportunities and teaches you method, not just grunt work

- Program-specific mentor: someone embedded in your dream program who can vouch for you or at least decode what that program really values

- Near-peer mentor: senior resident or fellow 3–5 years ahead of you who remembers what it feels like to be in your position

Conferences are uniquely good at finding the last two.

Residents and fellows: the undervalued network

Students fixate on big-name attendings and ignore the PGY-4 who actually runs the project they want to join. That is backwards.

At most big meetings, the people:

- Standing at posters for the full hour

- Moderating trainee sessions

- Sitting at the back of early morning workshops taking notes

are residents and fellows. These are your future chief residents, junior attendings, and fellowship faculty. They often have more time and more enthusiasm to mentor.

When you meet a resident/fellow who clicks with you:

- Ask directly what kind of work they do with students

- Ask what their own mentors value in a trainee

- Ask which programs seem to actually follow through on “supporting trainee research”

They can shortcut you months of guesswork.

Build a simple tracking system or you will lose people

Do not rely on your memory or a pile of business cards.

Use something simple:

- A spreadsheet with columns: Name, Role, Institution, Specialty/Subspecialty, How we met, Current connection level (1–5), Next action, Last contact date

- Or a note app with one note per person, tagged by specialty and program

After the conference, sit down for 30 minutes and enter everyone who seemed remotely valuable. Then prioritize:

- Level 5: Likely to become true mentor – schedule Zoom

- Level 3–4: Good connection – send thoughtful follow-up, maybe touch base quarterly

- Level 1–2: Low immediate value – connect on LinkedIn, keep minimal contact

It sounds clinical. It is. This is career-critical relationship management, not a casual social circle.

6. What This Looks Like Across An Actual Gap Year

Let me stitch this together into a realistic sequence. Assume you are taking a gap year between M3 and M4, planning to apply IM with interest in pulmonary/critical care.

| Period | Event |

|---|---|

| Pre-Year - Choose specialty focus | 1 month |

| Pre-Year - Select 1-2 key conferences | 2 weeks |

| Early Gap Year - Pre-conference outreach | 1 month |

| Early Gap Year - Attend main specialty meeting | 1 week |

| Early Gap Year - 48-hour follow-up & Zoom scheduling | 2 weeks |

| Mid Gap Year - Ongoing project work with mentors | 4-6 months |

| Mid Gap Year - Attend regional/subspecialty meeting | 1 week |

| Late Gap Year - Solidify letters & advocacy | 2 months |

| Late Gap Year - Prepare applications with mentor input | 1-2 months |

Concretely:

Months 1–2:

- Decide on ATS as main national meeting and CHEST or regional pulmonary meeting as secondary

- Work with current mentor to identify 8–10 target faculty and 10–15 target fellows/residents

- Send 8–12 pre‑conference emails, secure 3–5 “sure” meetings and 3–4 “maybe” meetings

Conference week:

- Attend 1–2 PD panels, introduce yourself briefly after

- Hit your pre-arranged coffees and “meet at my poster” interactions

- Make opportunistic contacts at posters and trainee mixers

- Each night, jot 3–5 bullet points about who you met and what they said

Within 48 hours post‑conference:

- Send personalized follow‑ups to 10–15 people

- For your top 3–5, propose Zoom calls within 3–6 weeks

- Update your tracking sheet with “next action” for each

Months 3–8:

- Start or join 1–2 projects with new mentors (even if remote data work)

- Email quarterly updates

- Ask strategic questions: “How would program X view a gap year at [place] vs [place]?”

- Attend a smaller regional meeting to reinforce connections (“Good to see you again in person” matters)

Months 9–12 (application season):

- Ask 2–3 of these conference-borne mentors for letters, with plenty of lead time

- Have at least one mentor review your personal statement and program list

- When interview invites roll in, ask the program-specific mentor: “What should I know before interviewing at your institution?”

You have effectively turned a single week at a conference into a year-long mentorship web.

7. Advanced Tactics People Rarely Talk About

You want the edge? Here are the things I see high‑performers do that almost nobody else does.

Co-present with your mentor if at all possible

Even a small co-authored poster, with your mentor physically there, changes the dynamic. They can introduce you:

“Let me introduce you to Alex, who did most of the legwork on this project and is applying into IM next cycle.”

That single sentence, in front of another faculty member, is soft advocacy that no cold email can touch.

If you do not have your own abstract, ask your mentor early: “If your group is bringing multiple projects, is there one where an extra presenter would be helpful? I’d be glad to share the load.”

Sometimes you get added late. Fine. Present anyway. You are buying credibility.

Volunteer for visible trainee roles

A lot of societies quietly recruit trainees to:

- Moderate poster sessions

- Take notes for guideline groups

- Serve on early-career committees

Those roles are networking steroids. Suddenly you are not just “some student.” You are “the trainee on the early-career committee,” which faculty recognize as a screen for basic competence.

Ask the society reps (usually at the membership or trainee booth): “Are there trainee committees or volunteer roles for next year? I would like to get involved early in my career.”

Use social media strategically, not obsessively

Live‑tweeting every session is pointless. But 3–5 high-value posts can:

- Signal your engagement in the field

- Provide a natural excuse to tag or DM a faculty member later (“I really appreciated your point about X in the session on Y”)

- Slightly increase your “name recognition” when people see your badge

Rule: do not tweet anything you would not be comfortable with your future PD reading out loud in a room.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Conference | 10 |

| 1 Month | 8 |

| 3 Months | 6 |

| 6 Months | 5 |

| 12 Months | 4 |

8. Common Failure Modes And How To Avoid Them

Let me be blunt. These are the patterns that derail otherwise smart trainees.

The Ghoster

- Has great conversations, then never follows up.

- Faculty assume lack of seriousness. Relationship dies.

The Ask-Too-Much-Too-Soon

- First email after a 5‑minute chat: “Will you write me a strong letter?”

- This is social malpractice. You have given them nothing to base it on.

The Flaky Collaborator

- Begs for a project, then misses deadlines, disappears for weeks.

- Word travels. This kills opportunities in ways you do not see.

The Conference Tourist

- Attends every big plenary, sits in the back on their phone, rarely speaks to anyone.

- Leaves saying “I did not really meet anyone helpful.” Of course you did not.

Avoid these and you are already in the top quartile of conference networkers.

FAQ (Exactly 4 Questions)

1. I have social anxiety / I am introverted. Can conference networking still work for me?

Yes, but you need structure. Focus on one‑on‑one or small-group interactions rather than big mixers. Pre-schedule 3–5 brief meetings via email so you are not cold‑approaching everyone. Use posters and after‑session questions as your main entry points—they give you built-in topics to discuss, which lowers the conversational load. You do not need to “work the room.” You need a handful of good conversations with the right people.

2. What if I email people before the conference and nobody replies?

That happens. Faculty inboxes are disasters. If you sent 10 good emails and get zero replies, you likely aimed too high (all national superstars) or wrote too generic notes. At the conference, still approach them briefly after talks or at posters, referencing the email: “I sent you a quick note last week, but I know things get busy.” Then follow up again after an in‑person chat. In practice, one or two solid interactions set up at the meeting can compensate for a cold email strikeout.

3. How long do I need to work with someone before asking for a letter of recommendation?

I would not ask after a single project or 4–6 weeks unless the relationship has been unusually intensive. You want at least 3–6 months of intermittent interaction—regular updates, some actual work product, and evidence you take feedback well. When you ask, be direct: “Do you feel you know me and my work well enough to write a strong, detailed letter for my residency applications?” That gives them an easy out if they cannot, which is better than a lukewarm letter.

4. Is it worth spending money on conferences during a gap year when finances are tight?

It can be, but only if you treat it as an investment and act accordingly. One strategically used national or major regional meeting that leads to a real mentor, a letter, and a project is worth far more than three aimless trips where you just “attend sessions.” Apply for every trainee travel grant, share rooms, and choose one primary conference to go “all in” on. If you cannot afford travel at all, prioritize virtual attendance but double down on pre‑meeting emails and post‑session Zooms to mimic the networking you would have done in person.

Three key points before you close this tab:

- Conferences are not about content; they are about people. You are going to acquire mentors, not tote bags.

- Effective mentorship from conferences is designed, not accidental: pre‑conference outreach, targeted in‑person contact, and disciplined follow‑up.

- A single well‑handled conference in your gap year can reshape your residency trajectory; most people waste that chance. Do not be one of them.