Group and panel residency interviews do not reward the “smartest” applicant. They reward the most prepared applicant.

If you walk into these formats thinking, “I’ll just be myself and see how it goes,” you have already lost ground to the person who has drilled their stories, practiced turn‑taking, and mapped out how to stand out without steamrolling others.

Let me walk you through a structured way to get ready, so you are not the shell‑shocked person walking out saying, “That was chaos…I have no idea how I did.”

1. Understand Exactly What Group and Panel Interviews Are Testing

Stop thinking of these as “just another interview.” Programs use group and panel formats to test things that 1‑on‑1 interviews do not expose well.

What a group interview is really measuring

Group = multiple applicants together with one or more interviewers. You might be:

- Solving a case or ethical scenario as a group

- Working on a hypothetical QI project

- Doing “get to know you” questions in a circle

- Debating a policy topic

They are evaluating:

- How you interact with peers

- Whether you listen or just wait to talk

- If you can lead without being domineering

- Emotional intelligence under social pressure

- Whether you make the room better or worse

What a panel interview is really measuring

Panel = multiple interviewers (faculty, PD, chief, resident, sometimes coordinator) and you.

They are evaluating:

- Consistency of your story under cross‑examination

- Poise when questions come rapid‑fire from different angles

- How you respond to conflicting personalities (the skeptical attending, the friendly resident, the silent PD)

- Your ability to track a conversation and adapt quickly

Stop asking, “What if they ask me X?” The better question:

“What are they trying to learn about me in this format, and how do I show it on purpose?”

2. Do Targeted Research That Actually Matters for These Formats

Most applicants either over‑research (hours on the website, nothing retained) or under‑research (skim the homepage in the Uber). Neither approach works for group or panel interviews.

You want lean, usable intel that you can deploy during discussion.

Build a 1‑page “Program Battle Card”

For each program, create a single sheet you can glance at before the interview. No novels. Just ammunition.

Include:

2–3 signature features

- e.g., “Strong county hospital exposure,” “Global health track,” “4+1 schedule,” “Night float system”

2 recent changes or initiatives

- New ED expansion

- New fellowship or track

- Curriculum overhaul

3–4 names with roles and 1 fact each

- PD: Dr. Smith – interest in medical education, published on resident wellness

- Associate PD: Dr. Lee – ED operations, QI tone-setter

- Chief: Dr. Patel – runs simulation curriculum

2–3 concrete reasons you fit this program

- “I thrive in high‑volume county settings”

- “Strong interest in QI aligns with their ED flow project”

This sheet is what you mine for:

- Group discussion references (“In a program like this with strong county experience…”)

- Panel questions for specific people (“Dr. Lee, I read about your QI project on throughput…”)

Research specifically for group scenarios

Programs that use group exercises often lean on:

- Ethics / professionalism dilemmas

- Systems‑based practice (how you’d improve a process)

- Teamwork in resource‑limited settings

Read:

- 3–4 brief ethics cases (AMA ethics, NEJM “Case Records” style)

- 1–2 high‑quality blog posts on common residency ethical scenarios:

- Impaired colleague

- Borderline unsafe attending

- Patient demanding inappropriate treatment

- Resource allocation

This does not make you a bioethicist. It just keeps you from freezing when you get a scenario that starts with: “You are a senior resident on nights…”

3. Build a Story Bank Optimized for Group and Panel Settings

If you show up to a panel or group relying on whatever story pops into your head, you will ramble. Or repeat yourself. Or worse, tell a story that sounds impressive but lands wrong with faculty.

You need a story bank: 8–10 short, flexible stories that you can adapt to different questions.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Identify Core Competencies |

| Step 2 | Select 8-10 Key Experiences |

| Step 3 | Write 3-4 Bullet Outline Each |

| Step 4 | Map Stories to Competencies |

| Step 5 | Practice Out Loud |

| Step 6 | Adapt for Group vs Panel |

Step 1: Identify the 6–7 competencies programs care about

For nearly every specialty, versions of these:

- Teamwork

- Leadership

- Communication / conflict management

- Resilience / handling failure

- Ethical judgment / professionalism

- Adaptability / learning from feedback

- Initiative / ownership

Step 2: Pick stories that do double duty

You want stories that can morph depending on question wording. Examples:

Difficult team dynamic on a rotation

- Teamwork, conflict management, professionalism

Patient safety near‑miss or adverse event

- Ethical judgment, communication, ownership

Big setback (bad eval, exam score dip, personal issue)

- Resilience, growth, insight

Leadership action (student group, QI project, curriculum)

- Leadership, initiative, systems thinking

Cross‑cultural or complex patient interaction

- Communication, empathy, adaptability

Time you gave or received brutally honest feedback

- Humility, growth mindset

Step 3: Script the skeleton, not the monologue

For each story, write:

- 1 sentence: context

- 2–3 bullets: what you did

- 1–2 bullets: outcome + what you learned

Aim for 60–90 seconds per story as your default. In group settings, be ready to compress to 30–45 seconds.

Then practice telling them:

- Full length (90 seconds)

- Compressed (45 seconds)

- “Headline only” (20 seconds) for rapid‑fire or follow‑ups

This flexibility is gold in both group and panel formats.

4. Master Group Interview Dynamics: How to Stand Out Without Being “That Person”

Most people screw this up. They either dominate (and annoy everyone) or vanish (and get forgotten). Both hurt you.

Here is the operating principle:

Your goal is to make the group look good while clearly contributing value.

What success looks like in a group interview

You:

- Speak multiple times in a way that moves the conversation forward

- Reference others’ ideas by name

- Add structure when things get messy

- Show calm, concise thinking

- Avoid arguing, grandstanding, or “performing medicine”

Programs are not trying to identify who can out‑debate everyone. They want to see who they would want in their 2 a.m. sign‑out room.

Concrete tactics during group discussions

- Volunteer to frame, not to dominate

You can score early points by saying something like:

“I’m happy to start us off with a possible approach, and then we can build on it together.”

Then you:

- Lay out a simple structure (Option A, Option B, factors to weigh)

- Stop. Invite others in: “What are others thinking?”

You look like a leader. Not a steamroller.

- Use names and build explicitly

Keep a mental tally of 2–3 other names. Use:

- “I agree with what Sarah said about patient safety, and I would add…”

- “Mark brought up a good point about resource limitations…”

This is subtle but powerful. It signals you are team‑oriented and paying attention.

- Advance the discussion, do not repeat it

If your comment starts with, “I basically agree with…” and then you repeat exactly what they said, you have wasted time.

Instead:

- Add a new dimension (patient’s social context, system implications, team well‑being)

- Or synthesize: “It seems like we are all circling around two main options…”

- Manage airtime strategically

If you notice:

- You have spoken 3 times and others only once → pull back slightly, invite others.

- You have not spoken yet and 5 minutes have passed → you need to jump in now.

Use entry phrases:

- “One thing we have not touched on yet is…”

- “To build on what has been said so far…”

If you tend to talk too much, rehearse 30–45 second contributions. Literally time them.

- Handle disagreement like a professional, not a debater

If you disagree:

- “I see the value in that approach, especially for X. My concern would be Y, so I might consider…”

Not:

- “I actually think that is wrong because…”

You can be decisive without being dismissive.

5. Dominate Panel Interviews Without Getting Rattled

Panels feel like an oral exam crossed with a firing squad. It is easy to get flustered.

The fix is predictable practice with the hard parts: shifting eye contact, managing multi‑part questions, and staying composed when someone is clearly testing you.

Basic panel mechanics you must drill

- Eye contact rule

- When asked a question: look at the person asking while they are speaking

- When answering:

- Start with the questioner

- Then sweep the rest of the panel periodically

- End your answer back on the questioner or the PD

- Answer length control

Panels have limited time. Your safe default:

- Behavioral questions (“Tell me about a time…”) → 60–90 seconds

- Opinion/fit questions (“Why this program?”) → 60 seconds

- Clarifications or follow‑ups → 20–40 seconds

If someone seems impatient, shorten further. You can literally say:

“I want to be mindful of time, so I will keep this brief.”

That line alone can rescue you from a ramble.

- Handle multi‑part questions like a professional

Panel questions often sound like:

“Tell me about a time you had a conflict on a team, what you did, what you learned, and how you would handle it differently now.”

Do not wing it. Train yourself to:

- Grab a pen. Jot down 3 key words on your pad: “Conflict – actions – learn/diff”

- As you answer, signpost:

- “First, the situation…”

- “What I did at the time was…”

- “What I learned, and what I would do differently now is…”

You will look organized and less anxious.

Dealing with panel personalities

You will repeatedly see these archetypes:

- The silent PD – says little, watches everything. You still periodically include them in your gaze, and include program‑level comments that speak to their role.

- The skeptical attending – asks the hard questions, challenges your answers. Stay calm, concrete, not defensive.

- The friendly resident – tries to put you at ease, may toss you “softball” questions. Do not blow these. They often carry hidden weight.

- The distracted faculty – scrolling on a laptop, checking notes. Do not personalize it; they still may be listening.

Your job is not to charm each one individually. It is to show consistency: same person, same story, same tone across all of them.

6. Build a Focused Practice Plan (2–3 Weeks Out)

If you have interviews coming, your calendar needs scheduled reps, not vague intentions like, “I’ll practice some answers this weekend.”

Here is a concrete 2‑week minimalist plan. Adjust timing if you have longer.

| Day Range | Focus Area |

|---|---|

| 1–2 | Story bank + program battle cards |

| 3–4 | Solo practice (panel style) |

| 5–6 | Mock group discussion |

| 7–9 | Mixed panel + behavioral drills |

| 10–11 | Second mock group + refine tactics |

| 12–14 | Light review + confidence reps |

Days 1–2: Build your foundations

- Finalize 8–10 story bank entries

- Create 1‑page battle card for each upcoming program

- Identify 3 “why this program” angles for each interview

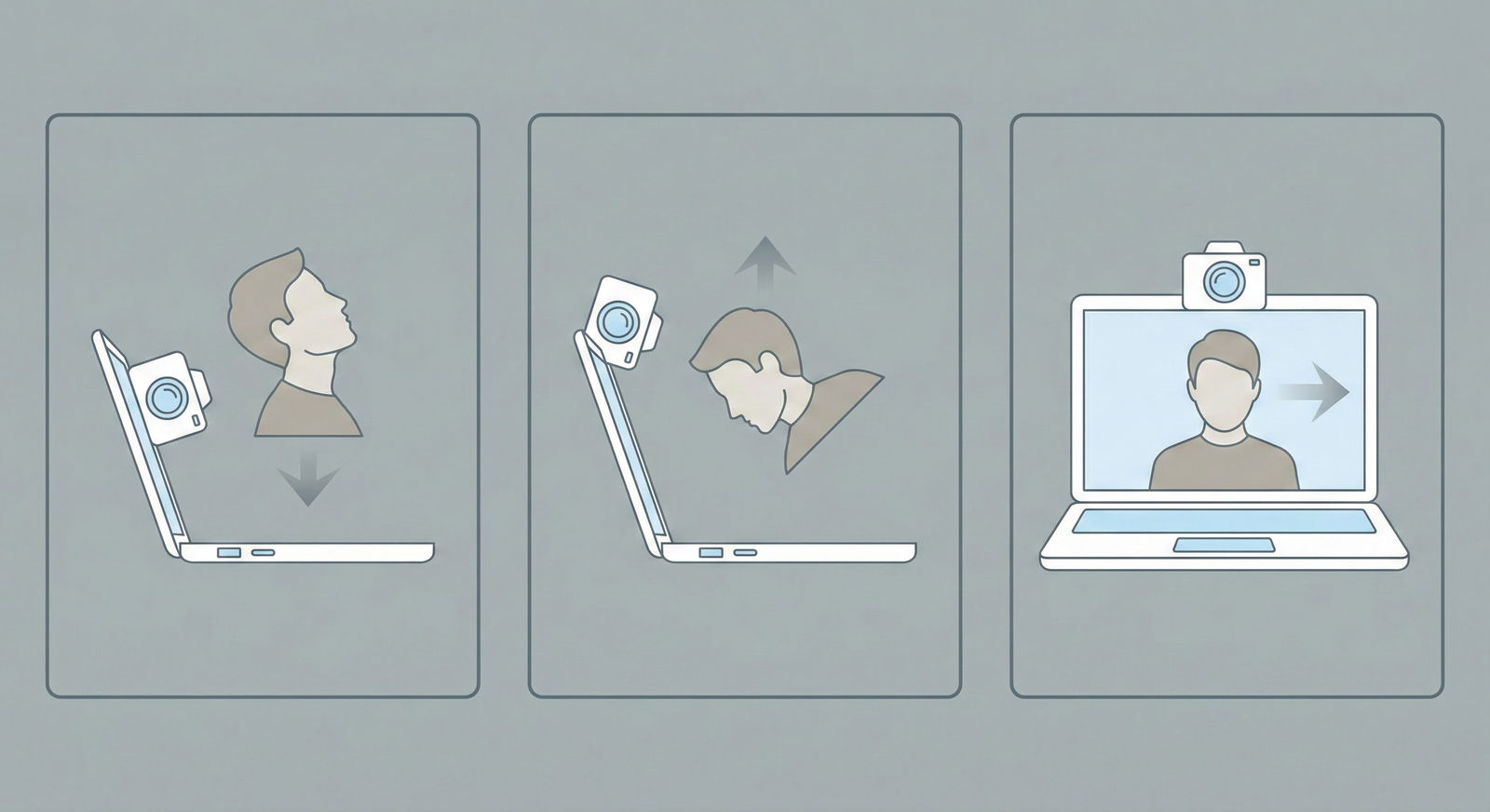

Days 3–4: Solo panel drills

- Record yourself (phone is fine) answering:

- “Tell me about yourself.”

- “Why this specialty?”

- “Why our program?”

- 3–4 behavioral questions

Watch yourself once with sound, once muted:

- With sound: listen for rambling, hedging, filler (“like,” “um,” “you know”)

- Muted: check posture, facial tension, weird hand movements

Fix 1–2 issues at a time. Do not try to be perfect.

Days 5–6: First mock group

You need other humans. If you cannot get real people, you can still simulate, but aim for:

- 3–6 friends applying to any specialty

- Assign a facilitator (maybe someone’s partner, a resident you know, or just rotate roles)

- Use 1–2 sample prompts:

- “You are senior residents on nights and…”

- “Your program has high resident burnout. Design an intervention…”

Record the session if possible.

Afterwards:

- Each person says: “One thing you did that helped the group, one thing that hurt.”

- Make one behavioral change goal for next time:

- “Speak up earlier.”

- “Cut answers by 15 seconds.”

- “Reference others’ ideas more.”

Days 7–9: Mixed drills

Alternate days:

- Panel practice with a friend or mentor acting as 2–3 panel roles

- Solo video practice focusing on:

- Multi‑part questions

- Ethics/“worst mistake” questions

- “Tell me about a time you had a conflict” style prompts

Days 10–11: Second mock group with tactics

Run another group session. This time, go in with explicit tactics:

- “I will speak in the first 2–3 minutes.”

- “I will use at least 3 people’s names.”

- “No answer longer than 45 seconds unless we are stuck.”

Then ask the group to call you out if you violate your own rules.

Days 12–14: Taper and sharpen

Do not cram new content now. Focus on:

- Reviewing program sheets briefly

- Light story refreshers

- 1–2 short mock panels

- Sleep, hydration, exercise

You want to walk into interview day warmed up, not mentally exhausted.

7. Use Simulation Tools Intelligently

You will be tempted to binge generic YouTube videos or do 20 sloppy mock interviews. That is noise. A few targeted simulations beat a pile of unfocused practice.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Solo Drills | 30 |

| Panel Mocks | 25 |

| Group Mocks | 25 |

| Program Research | 20 |

High‑yield practice formats

- Small‑group peer sessions

- Rotate roles: applicant, interviewer, observer

- Observers watch only one thing per round: concision, clarity, eye contact, or group dynamics

- Resident‑run prep sessions

If your school has residents offering mock interviews, take them. Tell them specifically:

- “I want you to be a harsh panel attending.”

- “Give me rapid‑fire questions for 10 minutes and then blunt feedback.”

You do not need them to be nice. You need them to be real.

- Time‑boxed drills

15 minutes:

- Set a timer

- Answer as many behavioral questions as you can, 60–90 seconds each

- No stopping, no rewriting

- This builds stamina and quick mental organizing

8. On the Day: Execution Protocol

If you have done the work, the day of the interview is not about magic. It is about not sabotaging yourself.

Pre‑interview routine (same every time)

2–3 hours before:

- Light meal with protein and complex carbs

- 10–15 minutes reviewing program battle card

- 5–10 minutes reviewing story bank bullets

- 3–5 minutes of out‑loud warm‑up:

- “Tell me about yourself” twice

- One behavioral story

- One “why this program”

Yes, out loud. Not in your head.

During group sessions

Remember your job:

- Be the person they want at 3 a.m. on a bad trauma night

- Calm, collegial, mentally sharp

Specific in‑the‑moment checks:

- Are you talking too much? Look around; if three others look like they want to speak, yield.

- Have you spoken at all? Force yourself in with, “I can add a brief thought to that…”

- Are you acknowledging others? Use names.

During panel interviews

- Sit slightly forward, feet grounded, hands loosely together

- If you blank on a question:

- “That is a thoughtful question. May I take a brief second to think?”

- Take 3–5 seconds. Breathe. Then answer.

If you truly do not know:

- “I do not have direct experience with that specific situation, but here is how I would approach it if it arose…”

That beats panicked word salad every time.

After each session

Do micro‑debriefs:

- One thing you did well

- One thing to fix in the next room (shorter answers, more structure, stronger “why us,” etc.)

Do not spiral over a single awkward answer. Faculty forget individual missteps more quickly than you think. They remember overall impression.

9. Common Mistakes That Quietly Kill Strong Applicants

I have watched very capable applicants sink themselves in group and panel formats with the same handful of errors.

Avoid these:

- Answering every question as if it is a personal branding pitch

Sometimes they just want to know how you think about duty hours. You do not need to tie it back to “ever since I was a child…”

- Turning group exercises into “Who knows the most medicine?”

You are not there to flex obscure guidelines. Focus on reasoning, communication, and patient‑centered thinking.

- Over‑sharing personal hardship without reflection

If you talk about trauma, mental health, or big life events, fine. But anchor it in:

- What you learned

- How you function now

- Concrete supports in place

- Talking badly about other programs, schools, or colleagues

Panel members will nod politely and silently downgrade you.

- Repeating the same story three different ways

Panel interviewers compare notes. If every answer is the same 2 patient encounters, you look shallow.

- Confusing “confidence” with “performance”

You do not need to act like a TED talk speaker. You need to be clear, grounded, and respectful. That is it.

FAQ

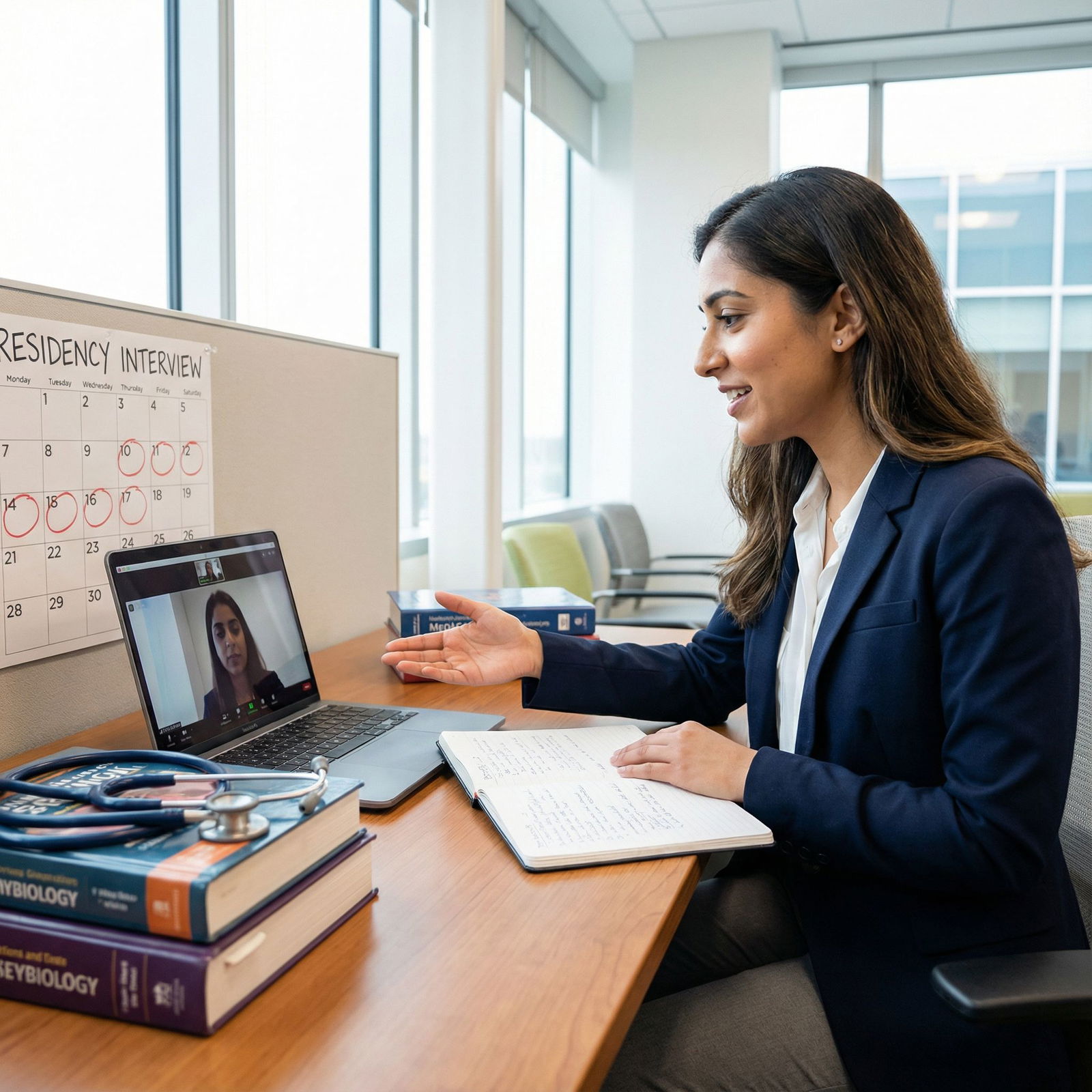

1. How different should my approach be for virtual vs in‑person group and panel interviews?

Core strategy is the same, but execution shifts slightly. For virtual, over‑index on clarity and timing: unmute quickly, avoid talking over others, and keep answers a touch shorter to account for lag. Use your name occasionally (“This is Alex, I agree with…”) because visual cues are weaker. For panel, look into the camera when answering to simulate eye contact, then glance at faces on screen between sentences. Test your setup (lighting, framing, sound) with a mock session; bad audio and dark video make you look less engaged even if your content is excellent.

2. What if I freeze in a group or panel interview despite practice?

You build a contingency plan now, not when you are panicking. If you freeze in a group, buy time with structure: “I see a few key issues here: patient safety, communication with the team, and system resources. Maybe we can start with safety…” You have contributed without needing a fully formed opinion yet. In a panel, use a reset phrase: “I want to answer this clearly; may I take a brief second?” Then silently count to three, pick one of your story bank entries or principles (patient safety, honesty, team communication), and build from there. Even a somewhat basic but organized answer beats a frantic, disjointed one.