Is Cramming Effective for USMLE Step 1? Rethinking Study Methods and Medical Learning

Preparing for the USMLE Step 1 is one of the most intense periods of medical school. Between lectures, small groups, clinical responsibilities, and personal life, it’s easy to feel behind and tempted to rely on last-minute marathons of studying. Many students wonder: Is cramming a viable strategy for Step 1, or is it a trap?

This article breaks down the science and practicality of cramming within the specific context of USMLE Step 1 preparation. You’ll learn when cramming helps, when it hurts, and which evidence-based Study Methods actually improve performance, retention, and long-term clinical reasoning.

The Nature of Cramming in Medical Education

Cramming typically means trying to learn a large volume of information in a very short time right before an exam. In undergraduate settings, it may have gotten you decent grades. In medical school and for the USMLE Step 1, though, the stakes and demands are different.

Step 1 doesn’t just test memorized facts. It evaluates your ability to integrate physiology, pathology, pharmacology, and biochemistry into complex clinical vignettes. This changes how effective cramming can be.

Why Students Cram

Cramming for Step 1 often emerges from:

- Time pressure and overload – heavy pre-clinical curricula, multiple tests, and looming exam dates

- Illusion of productivity – long hours of passive reading feel like “hard work,” even if retention is poor

- Anxiety and perfectionism – waiting until you “feel ready” to begin practice questions or focused review

- Procrastination and planning gaps – underestimating how long it takes to cover and revisit material

Recognizing why you lean toward cramming is the first step in designing a more sustainable and effective Step 1 strategy.

Cramming for Step 1: Pros, Cons, and Realistic Expectations

Cramming is not entirely useless—but it’s often misunderstood. Instead of asking “Is cramming good or bad?” it’s more helpful to ask, “What kind of learning does cramming produce, and is that what Step 1 rewards?”

Potential Short-Term Benefits of Cramming

- Boosted Short-Term Recall

If you review a drug mechanism or a list of enzyme deficiencies the night before a small quiz, you may recall it the next day. Cramming can temporarily flood your working memory with high-yield facts.

For Step 1, this might give a small edge with:

- Isolated fact-heavy questions (e.g., specific side effects, rare eponyms)

- Recently reviewed algorithms (e.g., vaccination schedules)

But Step 1 is not primarily a trivia exam, so this benefit is limited.

- Hyper-Focused Study Sessions

The pressure of an upcoming deadline can increase:

- Focus and concentration

- Willingness to block distractions

- Sense of urgency and motivation

Some students leverage this heightened focus to quickly close a few knowledge gaps near the end of their dedicated period—for example, doing a rapid, high-yield microbiology pass in the last week.

- Targeted, Last-Minute Review

When used intentionally, cramming-like sessions can help:

- Refresh weak topics you already learned but haven’t seen in a while

- Quickly review common formulas, equations, or mnemonics

- Skim summary tables or “rapid review” sections in resources like First Aid

In this narrow role—last-minute reinforcement—cramming can be useful.

Serious Drawbacks of Cramming for Step 1

- Superficial, “Surface” Learning

Cramming tends to create:

- Rapid, shallow familiarity instead of deep understanding

- Weak conceptual frameworks (e.g., memorizing side effects without understanding underlying pharmacology)

- Poor integration across disciplines (e.g., linking pathology to physiology and pharmacology)

Step 1 increasingly rewards conceptual understanding and clinical reasoning. Surface learning is fragile under exam pressure and complex vignettes.

- Poor Long-Term Retention

Cognitive psychology research consistently shows:

- Massed practice (cramming) → quick gains, fast forgetting

- Spaced practice (distributed learning) → slower gains, durable retention

For Step 1, this matters because:

- You’ll need the same foundational knowledge again for Step 2 CK and clinical rotations

- Concepts like acid–base balance, cardiac physiology, and immunology are “reused” across many organ systems and exam questions

Cramming may help you recognize a fact today but won’t help you use that concept six months later on the wards.

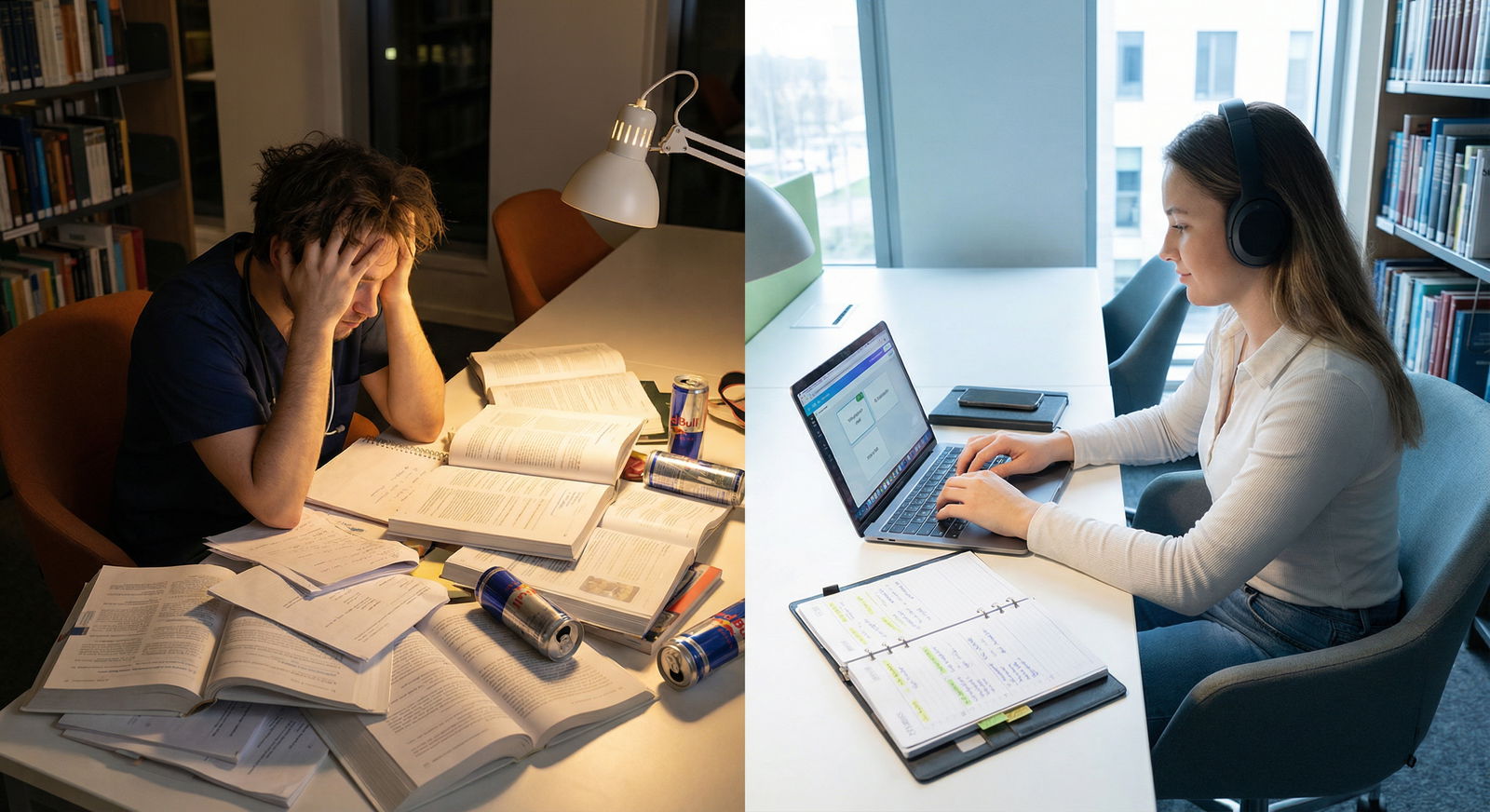

- High Stress, Burnout, and Reduced Performance

Cramming often coincides with:

- Irregular sleep or all-nighters

- Poor nutrition and less exercise

- Heightened anxiety and cognitive fatigue

Physiologically, sleep deprivation and chronic stress impair:

- Attention and working memory

- Complex reasoning and decision-making

- Emotional regulation and test-taking composure

That’s the opposite of what you want for a long, cognitively demanding exam like USMLE Step 1.

- False Confidence and Misleading Feedback

Cramming can create the illusion that:

- “I just reviewed this, so I must really know it”

- High performance on freshly reviewed questions equals true mastery

But when you see a similar concept days or weeks later:

- You may not recognize it in a different context

- Performance drops, leading to frustration and confusion

This disconnect can distort your self-assessment and make it hard to gauge real readiness.

Evidence-Based Study Methods That Work Better Than Cramming

To prepare effectively for USMLE Step 1, shift from passive review and last-minute memorization to Active Learning strategies grounded in cognitive science. These methods don’t just feel productive—they have strong evidence to support better memory and performance.

1. Spaced Repetition: The Antidote to Forgetting

What it is: Reviewing information at increasing intervals over time (e.g., 1 day, 3 days, 1 week, 2 weeks, etc.).

Why it works:

- It leverages the brain’s “forgetting curve” to strengthen memory each time recall becomes slightly harder.

- Repeated retrieval consolidates information into long-term memory, making it more resilient to stress and time.

Practical implementation for Step 1:

- Use spaced repetition platforms like Anki with premade high-yield decks or your own custom cards.

- Create cards for:

- Pathology mechanisms and classic presentations

- Pharmacology: mechanisms, side effects, contraindications

- Microbiology: organisms, virulence factors, treatments

- Commit to daily reviews, even during busy weeks—consistency matters more than intensity.

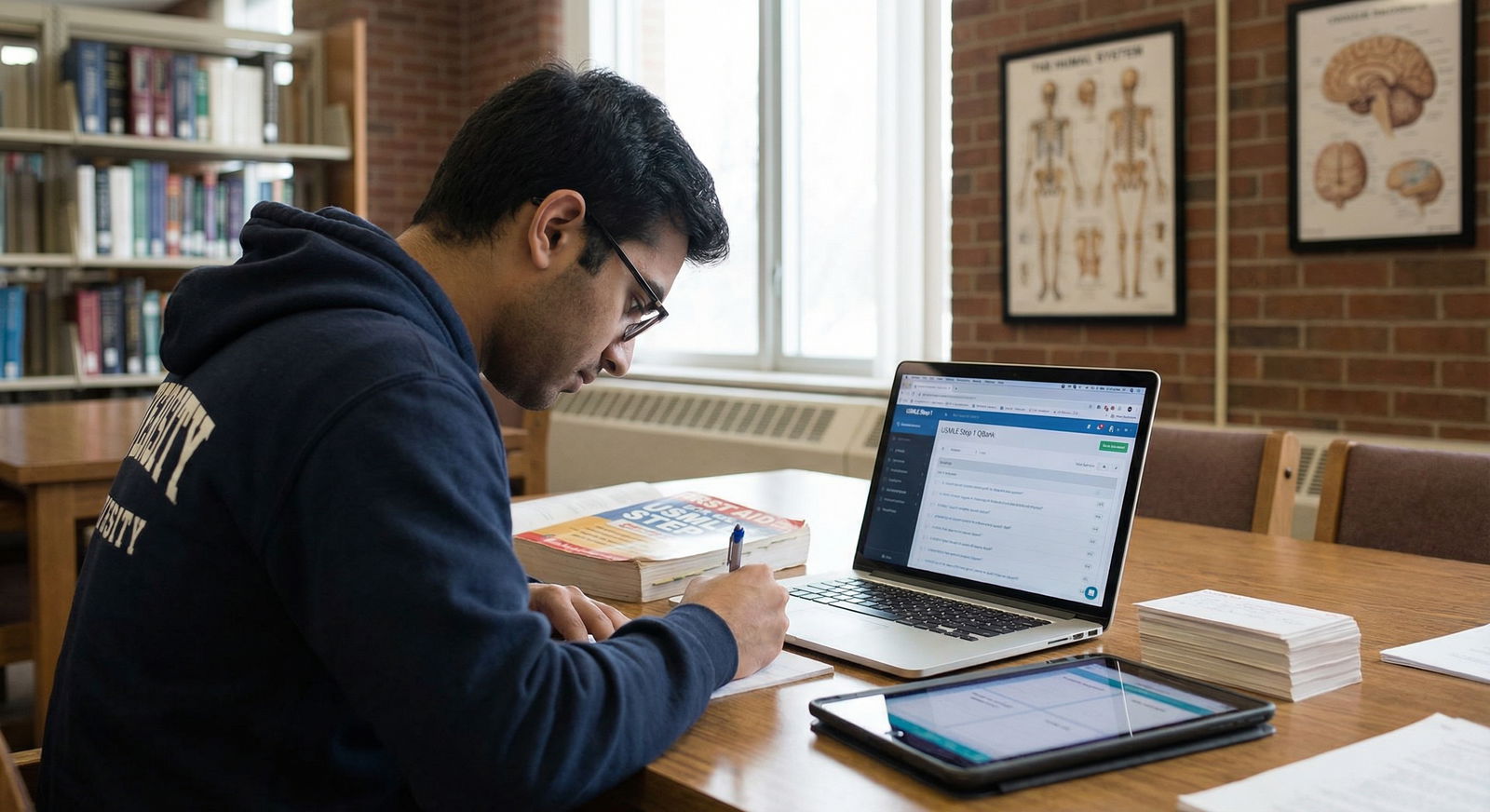

2. Practice Testing and Question Banks

What it is: Actively retrieving information by answering questions rather than passively rereading notes.

Why it works:

- Self-testing strengthens recall and helps you apply information in realistic exam-like contexts.

- It exposes weaknesses and blind spots you might not notice from notes or lectures.

- It improves exam-taking skills: timing, pattern recognition, and stamina.

How to use Q-banks for Step 1:

- Start early; don’t wait until “after I finish content review”

- Use UWorld, NBME practice exams, and other reputable question banks

- Aim for:

- Mixed blocks (interleaving disciplines) once you’re past the basics

- Timed sessions to simulate real exam pressure

- Careful review of explanations—often more valuable than the question itself

Tip: Treat every question as a learning opportunity. Even if you get it right, ask:

- Did I get it right for the right reason?

- Could I explain this to someone else?

- What underlying concept is being tested?

3. Interleaved Practice: Mixing Topics for Stronger Learning

What it is: Studying multiple subjects or systems in one session instead of doing long blocks on a single topic (blocked practice).

Why it works:

- Interleaving forces your brain to discriminate between similar concepts (e.g., different anemias, different types of shock).

- It more closely resembles how Step 1 mixes questions from all systems and disciplines.

Practical ways to interleave:

- Do question blocks that combine pathology, pharm, and physiology.

- Rotate systems daily: e.g., morning cardio, afternoon renal, evening biochem.

- Within a single system, mix different types of tasks: flashcards, questions, brief notes.

4. Building a Structured, Realistic Study Schedule

Cramming often reflects poor planning, not lack of motivation. A structured schedule converts vague intentions into a concrete roadmap.

Key elements of an effective Step 1 study plan:

Long-Term Timeline

- Map your study from early MS2 (or earlier) through your dedicated period.

- Build in time for:

- Initial content exposure

- Multiple passes and spaced review

- Practice exams and score tracking

- Buffer days for illness, fatigue, or unforeseen events

Weekly and Daily Goals

- Break large tasks into smaller, specific goals:

- “Finish 40 UWorld questions + review”

- “Review yesterday’s Anki + add 20 new cards”

- “Read endocrine chapters in First Aid and annotate key tables”

- Treat your schedule as a guide, not a prison—adjust based on performance and energy.

- Break large tasks into smaller, specific goals:

Balanced Study Modalities

- Combine:

- Flashcards (spaced repetition)

- Question banks (active application)

- Concise review resources (text or video)

- Avoid overloading on one method (e.g., only watching videos, only doing Anki).

- Combine:

Personalizing Your Learning: Finding What Works Best for You

Not all Study Methods work equally well for every learner. Understanding your own tendencies can help you avoid unnecessary cramming and design more efficient routines.

Identifying Your Learning Preferences (Without Overemphasizing “Learning Styles”)

The concept of rigid “learning styles” (visual, auditory, etc.) is often overstated, but preferences still matter. You can adapt evidence-based tactics to your natural inclinations.

Examples:

- If you prefer visual organization:

- Use mind maps, concept diagrams, and color-coded pathology trees.

- Summarize pathways (e.g., complement system, coagulation cascade) visually.

- If you learn through explaining:

- Teach a peer or “teach an imaginary student” out loud.

- Join or form small, focused study groups for difficult systems.

- If you need structure:

- Use digital planners or apps to schedule daily tasks.

- Set alarms for start/stop times and review blocks.

Avoiding Common Pitfalls That Lead to Cramming

- Passive reading instead of active engagement

- Replace “reading First Aid cover to cover” with “using First Aid as a reference while doing questions.”

- Over-resourcing

- Limit yourself to a primary set of resources (e.g., First Aid, Pathoma, Boards and Beyond, UWorld, Anki) rather than constantly adding more.

- Perfectionism and fear of questions

- Start practice questions early even if you feel underprepared. They teach you; they’re not just for assessment.

Consistent Review and Health: Foundations of Sustainable Step 1 Prep

“Study harder” is not always the answer. For USMLE Step 1, studying smarter and sustainably is far more effective than heroics in the final weeks.

The Role of Regular Review

Instead of panicked, last-minute review:

- Schedule daily and weekly review sessions for:

- High-yield flashcards

- Missed questions and notes from explanations

- “Rapid review” concepts at the end of each system

Examples of consistent review habits:

- 1–2 hours each morning for Anki or other spaced-repetition flashcards

- Short 10–15 minute review blocks between longer study sessions

- Weekly “cumulative review” of topics covered in the past 2–3 weeks

Over time, this approach reduces the need for emergency cramming because you’re constantly reinforcing older content.

Sleep, Health, and Cognitive Performance

Cramming often sacrifices sleep and self-care, but these are non-negotiable for high-level cognition.

Sleep and Step 1 performance:

- Sleep consolidates memory—especially the kind of integrated knowledge Step 1 demands.

- Pulling all-nighters or chronically sleeping poorly:

- Impairs executive function and concentration

- Increases anxiety and emotional reactivity

- Reduces accuracy on complex, multi-step questions

Practical health strategies during Step 1 prep:

- Aim for 7–8 hours of sleep most nights, especially in the 1–2 weeks before the exam.

- Incorporate brief movement:

- 10–20 minute walks

- Simple bodyweight exercises or stretching between blocks

- Maintain stable nutrition and hydration to avoid energy crashes.

- Use short mindfulness or breathing exercises to reset when stress spikes.

When (and How) Cramming Can Be Acceptable for Step 1

While cramming should not be your primary strategy, it can have a limited, strategic role.

Situations Where Limited Cramming Can Help

Final 24–72 Hours Before the Exam

- Brief, focused review of:

- High-yield rapid review lists

- Formulas and equations (renal clearance, anion gap, statistics)

- Common bugs–drug pairs and classic associations

- Brief, focused review of:

Reinforcing Memorization-Heavy Topics

- If your spaced repetition and content review are mostly in place, a short “cram pass” of:

- Microbiology organisms and treatments

- Biochemistry rate-limiting enzymes

- Pharmacology summary tables

- If your spaced repetition and content review are mostly in place, a short “cram pass” of:

Very Small Quizzes or Block Exams

- For in-course medical school exams worth a small portion of your grade, limited cramming might be tolerable. But keep in mind: these topics will likely return on Step 1 and in clinical practice, so deeper learning is still wise.

Structuring “Smart Cramming”

If you choose to cram near exam day, do so intentionally:

- Focus on high-yield, frequently tested material—not obscure details.

- Use active recall even while cramming:

- Rapid-fire self-quizzing

- Closed-book recall followed by quick checks

- Avoid sacrificing sleep the night before the exam. A well-rested brain outperforms an exhausted one with a few extra isolated facts.

The Real Goal: Balance, Not Extremes

Rather than pendulum swings between prolonged procrastination and frantic cramming, aim for:

- Consistent daily work

- Strategic review bursts

- Occasional short, intense sessions only when needed and not at the cost of your health

This “steady upward trajectory” is far more effective for both Step 1 and your long-term development as a clinician.

FAQs: Cramming and Effective Study Methods for USMLE Step 1

1. Is it realistically possible to “cram” for USMLE Step 1 and still pass?

It is possible for some students to pass with heavy reliance on cramming, especially those with a strong baseline from coursework. However, this approach is risky and generally not optimal. Step 1 draws on integrated, conceptual understanding built over months or years. Cramming may help you recall some last-minute facts, but it will not reliably support complex reasoning across an 8-hour exam or long-term retention for clinical practice.

A safer strategy is to build a strong foundation using spaced repetition and question banks, then use limited “cram-style” review only in the final days for quick refreshers.

2. How can I prevent myself from falling into cramming during my dedicated Step 1 period?

To avoid defaulting to cramming:

- Start question banks and spaced repetition early, not after finishing “all content.”

- Create a realistic, written study plan with daily and weekly goals.

- Regularly take practice NBMEs to gauge progress and adjust, rather than panicking at the last minute.

- Use accountability: study partners, mentors, or advisors who can help you stick to structured routines.

If you notice yourself slipping into last-minute all-nighters or chaotic topic jumps, pause and reset your plan rather than pushing harder in a disorganized way.

3. What are the most effective active learning strategies specifically for Step 1?

For USMLE Step 1, high-yield Active Learning strategies include:

- Spaced repetition flashcards (Anki or similar) for facts and associations

- Question banks (UWorld, NBME-style questions) for application and pattern recognition

- Teaching others or speaking concepts out loud to consolidate understanding

- Interleaved study sessions that mix subjects and question types

The combination of these methods—used consistently over time—is more powerful than any single resource or last-minute cramming effort.

4. How important is mental health and self-care during Step 1 preparation?

Mental health and self-care are crucial. Chronic stress, burnout, and sleep deprivation harm:

- Memory and concentration

- Decision-making under pressure

- Emotional resilience during a long exam

Integrate:

- Regular sleep (7–8 hours)

- Short daily physical activity

- Scheduled breaks and rest days

- Mindfulness, counseling, or peer support if you’re struggling

A clear, rested mind is a performance enhancer that no amount of cramming can replace.

5. Which core resources should I prioritize to avoid overwhelmed, scattered studying?

While resource preferences vary, many successful students focus on a core set and resist constant switching. Commonly used backbone resources include:

- UWorld (primary question bank)

- First Aid for the USMLE Step 1 (concise reference and framework)

- Anki (for spaced repetition)

- Pathoma and/or video series like Boards and Beyond for conceptual understanding

Choosing a limited, complementary set of resources and using them deeply is far more effective—and less likely to lead to crisis cramming—than constantly adding new materials.

By replacing cramming with structured, evidence-based Study Methods—spaced repetition, active recall, interleaved practice, and consistent review—you build not only a stronger performance on USMLE Step 1, but also the durable medical knowledge and reasoning you’ll rely on throughout residency and beyond.