The fastest way to look clueless on rounds is to use a great resource in the wrong way.

Review books are not the problem. How you use them—where, when, and how visibly—is what gets judged. And yes, you are being judged.

Faculty will never put this in a syllabus. But there’s a very real hidden curriculum around using Pocket Medicine, Step-Up, First Aid, On Call, even UpToDate on your phone. You’ve probably already felt it: that uneasy “am I allowed to look this up right now?” moment outside a patient’s room.

Let me tell you what actually happens behind the scenes.

What Attendings Really Think About Review Books

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: most attendings used these same review books as students. Many of them still have dog-eared copies in their offices. They know they’re useful. They’re not mad that you use them.

They’re mad when you look like you’re relying on them instead of thinking.

On a medicine service one July, I heard an attending tell the senior after rounds, about a third-year: “She had Pocket Medicine open the whole time. I don’t know if she knows anything that’s not on that page.”

That’s the core fear: that you’re reading instead of reasoning.

Attendings divide students into two buckets:

- The ones who use resources to sharpen their thinking

- The ones who hide behind resources to avoid thinking

Same book. Very different perception.

Most of this judgment happens in seconds, based on micro-behaviors: when you pull out the book, what your face looks like when you’re reading, whether you speak before or after you look something up.

You will never get feedback on this directly. You’ll just see words like “independent,” “prepared,” or “needs to work on clinical reasoning” on your evals, and wonder what that really meant.

The Basic Rule: Think First, Then Check

On rounds, the hierarchy is simple: brain → prior knowledge → team → resources.

If you flip that order, you look weak.

Here’s what strong looks like:

Attending: “What’s your initial antibiotic choice for this CAP patient with no comorbidities?”

Good student: “I’d start ceftriaxone plus azithromycin. If she were stable enough as an outpatient, high-dose amoxicillin plus azithro would be reasonable. I want to double-check local resistance after rounds, but that’s my starting point.”

Then later, while the team is writing orders or moving between floors, you flip open your pocket book to verify doses and durations.

Weak looks like this:

Attending: “Antibiotic choice?”

Student: Stares. Reaches for Pocket Medicine. Eyes drop to the page. Silence.

That’s the unspoken rule: you’re expected to commit before you check.

I’ve sat in workrooms where an attending turned to the resident after an interaction like that and said, “She doesn’t even try to reason it out. Goes straight to the book.” And yes, that colors their final evaluation, even if they never say it to your face.

The Visibility Problem: Same Content, Different Optics

A lot of this is optics. The content in your pocket book isn’t the issue. It’s whether you’re telegraphing “I’m unprepared” or “I’m thorough.”

Let me spell out how it actually plays out.

You pull out Pocket Medicine on rounds. Here’s how different people read that:

- The attending: “Is this student reviewing or replacing their knowledge?”

- The senior: “Do I trust this person to handle scut without me triple-checking everything?”

- The intern: “Is this person going to slow us down because they’re glued to a book?”

You want your behavior to answer those questions in your favor.

There are three concrete domains where review-book behavior gets silently judged:

- Timing

- Body language

- Integration into discussion

If you get those right, you can have a review book in your pocket every single day and still be seen as sharp, prepared, and safe.

If you get them wrong, that same book becomes a visual label that says: “I don’t know what I’m doing.”

Timing: When You Can and Cannot Use Review Books

The worst time to open a review book is when someone is looking directly at you.

Absolutely the wrong times

These are non-negotiable. I’ve watched students tank their reputations in one week ignoring these.

- While the attending is asking you a question

- While you’re presenting a patient

- While you’re standing at the bedside with the patient listening

- During teaching moments where the attending is clearly “pimping” to assess baseline knowledge

The hidden rule: if the current focus is your brain, your book stays closed.

I remember an OB/GYN attending who gave a mid-rotation feedback talk. She never mentioned exam scores, never mentioned grades. But she did say this: “If I see you looking something up while I’m asking you about it, I assume you didn’t prepare.” That’s the quiet standard.

Safe, smart times

There are windows to use review books without penalty. In fact, you look better for it if you do it quietly and purposefully.

- While you’re waiting for labs or transport between wards

- After you’ve presented, and the team has moved on to another patient

- In the team room right after rounds to lock in what you just learned

- The night before, to prep for the next day’s likely topics

On one busy medicine service, a resident pointed out a star student to me: “He always circles back after rounds; I’ll see him with Pocket Medicine open, cross-checking what we talked about. That’s the student I’ll go out of my way to help.” Same book. Different timing. Different impression.

Simple rule: use review books off stage, then bring the knowledge on stage.

Body Language: How to Look Like You’re Studying, Not Hiding

This is the part nobody spells out, but everyone reacts to.

Two students, same hallway, both with a book.

Student A: Back against the wall, book inches from their face, eyes down, oblivious to the team’s movement.

Student B: Book held low, one eye on the team, actively tracking where they’re going, tucking the book away as soon as the attending starts speaking.

Guess which one gets called “engaged” on their eval.

Faculty read your posture and micro-expressions more than you think. Certain behaviors send the wrong message:

- Turning your body away from the group to read

- Frowning intensely at a page while someone is teaching

- Needing multiple extra seconds to “come back” from the book when addressed

Contrast that with this line I heard from a pediatrics attending praising a student: “She jotted something quick in her notebook, probably a reminder to look it up later, but she stayed present for the teaching.”

You want your body language to say: “I’m here, I’m tracking, and I’ll deepen this later.”

That’s why a small notebook often plays better than an obvious, branded review book in your hand. Jot the topic. Look it up later. You still get the knowledge without signaling “I’m lost right now.”

The Ranking of Resources: What’s Socially Acceptable

Let me give you the unofficial hierarchy of on-rounds resources as many attendings see it:

| Resource Type | Typical Faculty Perception |

|---|---|

| Handwritten pocket notebook | Highly positive |

| Printed hospital guideline | Positive |

| Pocket Medicine / Sanford Guide | Neutral to positive (used well) |

| Phone with UpToDate open | Neutral to negative (context) |

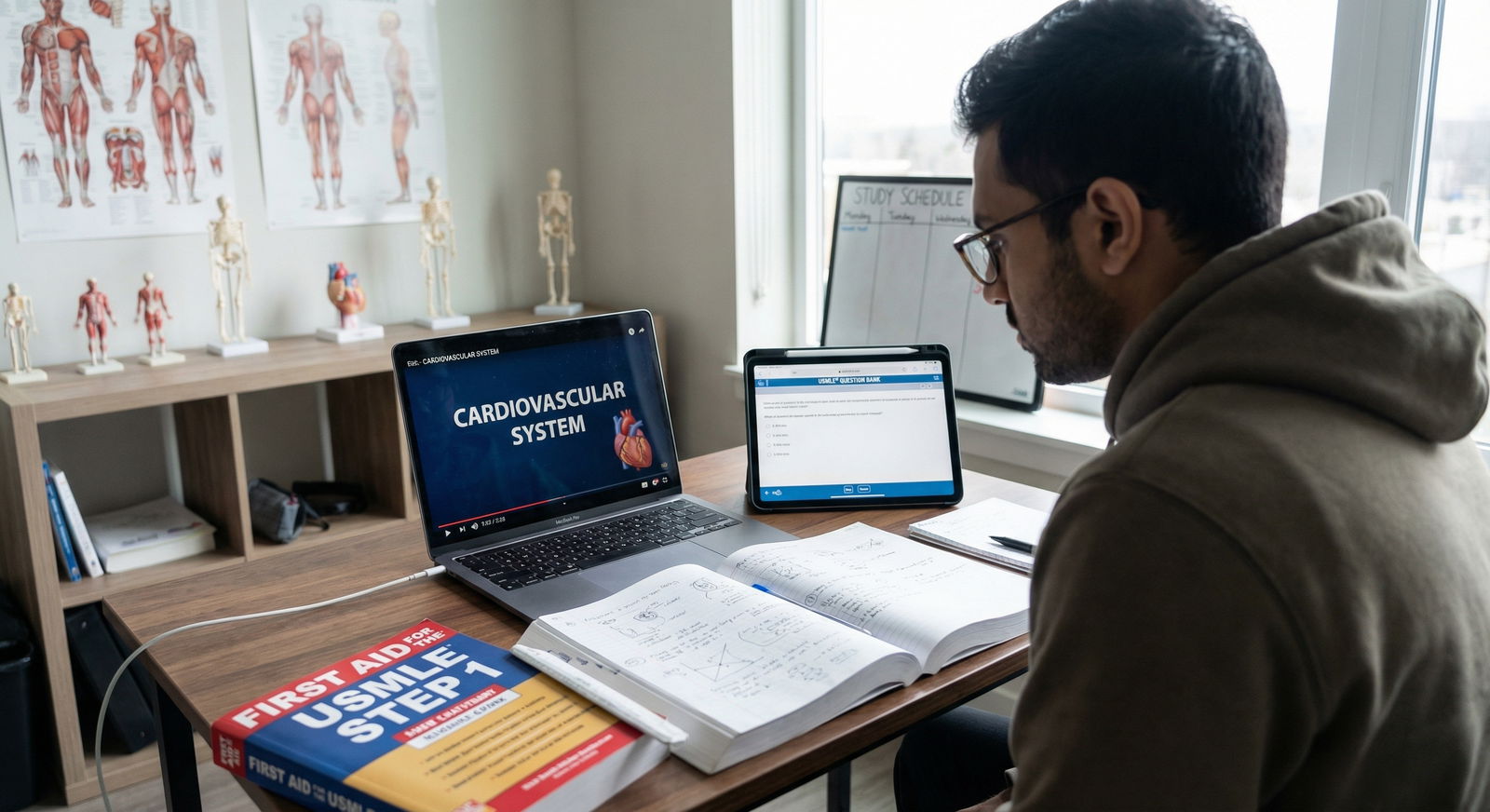

| First Aid / Step-style review book | Negative on rounds |

No one will admit this on a policy level. But I’ve listened to enough attending workroom conversations to know this is real.

A handwritten notebook suggests you’re integrating what’s taught. Hospital guidelines suggest you’re aligning with local standards. Pocket references, used briefly and then pocketed, are fine.

The big Step books? Those are exam resources, not clinical tools. Pulling out First Aid on a gen surg case? That screams “I care more about Step than this patient.” Fair or not, that’s how it hits.

UpToDate on your phone lives in a gray zone. A few attendings love it and will say, “Let’s look that up.” For others, phone out = distracted, texting, Instagram. Unless your department culture is explicitly pro-phone-learning, you’re safer with paper references in front of attendings.

Use UpToDate all you want in the workroom. But on rounds, if you must, say out loud: “I’m going to pull up UpToDate to check the dosing” so it reads as intentional, not sneaky.

How Strong Students Actually Use Review Books

The best students I’ve seen treat review books like a scalpel, not a blanket.

They’re not flipping randomly. They’re targeting.

Here’s what they do that most of your classmates don’t:

They preview. On a night float rotation, a medical student told me: “I skim Pocket Medicine’s syncope and chest pain sections before every shift. So when it comes up, I’ve already seen the structure once.” Attending feedback on that student? “Very organized and systematic thinker.”

They pattern-match. After seeing a few cases of pancreatitis, the good student goes back to a review book and compares: “What did I actually see vs what’s written?” That’s how you convert disorganized patient experiences into Step-style frameworks without looking lost in front of the team.

They annotate. The book is not pristine. Margins filled. Asterisks next to key tables. Brief notes like “Dr. X said they prefer Y here.” When an attending glimpses that, they read it as investment, not cramming.

And they time-shift. They don’t try to fix gaps in real time while under the spotlight. They capture topics and cure them that night. That way, tomorrow they look mysteriously “on top of it,” as if they just know things.

There’s no magic. Just disciplined use of the tool outside of high-visibility moments.

The Risk of Looking “Step-Brained”

On every core rotation there’s at least one student who gets labeled “Step-brained.” That’s not a compliment.

That’s the student who, when the team is wrestling with whether to hold anticoagulation for a procedure, says, “For Step, they love to ask about…” while the actual patient is an afterthought.

You can smell this mindset from twenty feet away. Attendings hate it. They all took the exams. None of them want to feel like they are props in your test-prep world.

Your review book choice and how you quote it will either reinforce or avoid that label.

If you say, during rounds, “First Aid says…” you’ve outed yourself. Wrong reference for that context. There is a reason most clerkship directors quietly roll their eyes at students carrying big Step review books around the wards.

A better move is framing: “From what I’ve read in Pocket Medicine and UpToDate, this is usually managed with X unless Y. In this patient, I’d lean toward…”

Same underlying prep. Entirely different frame. One sounds like “I studied boards.” The other sounds like “I’m practicing medicine and used resources to prepare.”

How Program Directors Interpret This Later

You think this stuff ends with clerkship evals. It doesn’t.

When you apply to residency, the comments from your third-year rotations follow you. Program directors read them, often quickly but with a very fine-tuned radar for certain words.

The hidden curriculum link is this: how you used resources on rounds shows up months later as coded language.

Comments like:

- “Independent learner”

- “Quick to look things up and follow through”

- “Prepared for rounds”

Often trace back to students who did their resource work pre- and post-rounds.

On the flip side:

- “Requires close supervision”

- “Struggles to apply knowledge at the bedside”

- “Needs to develop clinical reasoning skills”

You’d be surprised how often those started with repeated in-the-moment resource dependence. The student who could never answer without a book. The one always scrolling on their phone mid-rounds.

No one writes “Uses Pocket Medicine badly.” They write “Needs to improve X,” and program directors know what X often means.

This is why the hidden curriculum matters. You think you’re just using a book. They think they’re watching your future as a resident under pressure.

The Workroom Is Different: How Far You Can Go There

Now, let’s be fair. The team room is a very different arena from hallway or bedside rounds.

In the workroom:

- You should have resources open. Books, UpToDate, guidelines.

- It’s acceptable to say, “Let me check Pocket Medicine to confirm the dosing.”

- Nobody expects you to have every number memorized.

But there are still lines.

If every single question from the intern—“What labs does this need?” “What’s the follow-up imaging?”—leads to you flipping frantically through a review book, they’ll peg you as slow and inefficient.

That’s where targeted prep pays off. If you’re on cards, you should not be searching “CHF labs” for the first time on Day 10. You had all week to make that a pattern in your head, with the review book as scaffolding.

Use the workroom to build algorithms in your brain. Not just to copy answers.

You’ll notice the strong students start with: “I think we need CBC, BMP, Mg, and a CXR; I’m just going to quickly verify if we should add PFTs based on guidelines.” Then they open a resource.

The weak student silently stares at a book for 90 seconds and then recites a list without any context or prioritization.

Same tools. Different posture. Different evaluation.

How to Prep with Review Books Before Rounds

If you want the honest, slightly brutal truth: 80% of how “smart” you look on rounds was decided the night before.

On a good rotation, you’re not guessing what’s coming. You know your census. You know your service (GI? Cards? Heme/Onc?). You know your patients.

Here’s how the smart ones use review books outside the spotlight:

They do micro-prep. 15–20 minutes per common problem on their service, cross-referencing review books with one higher-yield source (UpToDate, a guideline, or a concise protocol). They’re not trying to memorize; they’re building familiarity with the structure.

They anchor to patients. If you saw COPD exacerbation today, that night you skim the COPD section of your review book specifically asking, “What did I miss? What would I do differently tomorrow?” Experience first. Book second. That sticks.

They predict teaching. On an ID service, you know someone’s going to ask about SIRS vs sepsis criteria, source control, or duration of therapy. If you’ve looked up just those few topics the night before, you’ll look “quick” on rounds. It’s not IQ. It’s quiet preparation.

Review books are lethal in this role because they’re compact and structured. But again, the key is off-stage use.

Bring your upgraded brain to rounds. Leave the heavy lifting of learning for the times when no one’s grading your every micro-move.

What to Do Tomorrow Morning

There’s no reason to overcomplicate this. Here’s the simple, pragmatic reset you can start tomorrow:

Use a small notebook on rounds. Jot down topics to review rather than burying your nose in a book every time you feel uncertain.

Keep Pocket Medicine or a similar review book in your coat—but treat it like a reference for after you’ve already given your best answer.

Stop bringing giant Step books onto the wards. They belong on your desk, not beside a patient.

And above all, commit out loud before you check. “Here’s what I’d do, and I’ll verify the details right after rounds.” That single sentence changes how people see your entire learning process.

You’re in that strange middle ground now—still in school, but starting to be judged as if you’re almost a doctor. The tools haven’t changed that much from your preclinical years. The expectations around when and how you use them absolutely have.

Mastering that hidden curriculum is part of the real exam you’re taking every day. The one that decides who gets the strong letters, the quiet advocacy, the whispered, “You should really take this student in your program.”

Get this piece right, and review books become one of your sharpest advantages instead of a silent liability.

With that foundation in place, you’re ready for the next layer of unspoken rules: how attendings really judge your questions, your notes, and your “interest in the specialty.” But that’s a conversation for another day.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| On-Rounds Learning | 25 |

| Workroom Study | 30 |

| Post-Call Review | 25 |

| Pre-Rounds Prep | 20 |

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | See Patients |

| Step 2 | Present on Rounds |

| Step 3 | Note Topics in Pocket Notebook |

| Step 4 | Reinforce Knowledge |

| Step 5 | Post-Rounds Review with Books |

| Step 6 | Apply on Next Days Rounds |

| Step 7 | Knowledge Gaps? |