82% of US MD seniors who took Step 1 in 2022 reported using First Aid as a primary resource—yet Step score distributions haven’t magically shifted upward in a decade.

So if “everyone uses First Aid” and “First Aid is the Bible,” why haven’t scores skyrocketed? Because First Aid is a reference manual, not divine revelation. And treating it like scripture is one of the quiet ways students cap their own ceiling.

Let’s strip the mythology off this book and look at what the data actually supports.

The First Aid Myth vs. Score Reality

There’s a script most M2s have heard word-for-word:

“Just memorize First Aid cover to cover and you’ll crush Step.”

I’ve heard attendings repeat this like it’s 1998. Meanwhile, the testing landscape changed and the book did not keep up in the way students imagine.

Look at the macro-level numbers. Using aggregated NBME/NRMP data and score reports over the last decade, the Step 1 mean hovered roughly in the mid‑230s until the pass/fail switch. During those years, First Aid adoption approached near-universal usage.

If First Aid “alone” were enough, the logical outcome would be a right-shift of the entire score distribution as more people followed the One True Path.

That never happened.

Instead, what we saw (and what many school curriculum committees quietly admitted in their internal reviews) was this pattern:

- Students who did only content review (First Aid, Pathoma, maybe Boards & Beyond) but little to no questions plateaued at “safe pass / low 220s” territory in the numeric era.

- Students who leaned heavily on Qbanks + NBMEs and used First Aid as a lookup / summary climbed into the high‑230s, 240s, and above.

The consistent differentiator wasn’t who could quote page numbers from First Aid. It was who could think through novel questions under time pressure.

First Aid doesn’t train that. It was never designed to.

What First Aid Actually Is (And Is Not)

Call it what it is: First Aid is a high-yield bullet-point index of Step‑relevant facts. It’s essentially a densely packed outline of “stuff you should have seen somewhere.”

That has value. But it also has sharp limits.

It is not:

- A concept-teaching textbook

- A question bank

- A clinical reasoning curriculum

- A complete representation of what’s on Step

When you read through real USMLE test-taker debriefs and correlate with NBMEs, a pattern shows up: a lot of frustration about questions that integrated physiology, pharmacology, and pathology in ways that weren’t just “one-line from First Aid.”

For example, students repeatedly described stems like:

- A complex endocrine vignette that requires understanding feedback loops and receptor dynamics, not just memorizing “drug X → side effect Y.”

- Immune pathways where you have to reason through what happens if you knock out a signaling molecule, not just identify which cytokine is “hot T‑bone stEAk.”

You can absolutely find the component facts in First Aid. But Step doesn’t ask “component facts” anymore. It asks: can you put those facts together in a new way?

A static outline is poor at training you to synthesize. It’s even worse at training test-taking behavior: timing, triage, dealing with uncertainty, prioritizing partial knowledge.

Yet students cling to it because an outline feels controllable. You can highlight it, annotate it, check off pages. Question banks, in contrast, are humbling and messy.

So people over-invest in the thing that feels safe. Not the thing that actually moves their score.

Content Coverage: Where First Aid Misses the Mark

Let’s be specific. When students compare First Aid to the content actually tested on NBMEs and the real exam, there are three recurrent problems.

1. Integration across disciplines

On real exams, you don’t get “pure pharm question” followed by “pure micro question.” You get combinations:

- A pharm question embedded in a path vignette with a physiology twist.

- A micro question that’s really about public health counseling.

- A genetics question that’s actually testing ethics and risk communication.

First Aid’s structure—separate micro, pharm, path, etc.—encourages siloed learning. Students memorize bugs, then drugs, then diseases. The exam punishes siloed learning.

You see this when a student can instantly rattle off that digoxin inhibits Na⁺/K⁺ ATPase, increasing intracellular Ca²⁺, but then completely falls apart on a question that asks them to predict the effect of renal failure plus amphotericin B on digoxin toxicity. The ingredients are in the book. The connection is not.

2. Conceptual depth

The book is intentionally shallow. That’s its pitch: high‑yield only. The problem is that “high‑yield” for 2024 test design isn’t just “names and lists.” It’s mechanisms, causal reasoning, and pattern recognition.

Take acid-base. First Aid gives you the formulas, the patterns, maybe a chart. Fine. But NBME-style questions want you to reason:

- What happens to serum bicarb and chloride after a specific type of diarrhea?

- How does compensation change if the underlying issue is mixed respiratory and metabolic?

If you never did proper concept work with a good physiology resource or questions, your “memorize the box” approach implodes.

3. Clinical nuance

First Aid gives the clean version. Real patients—and real test questions—are dirty.

- First Aid: classic triad of disease X.

- Step: older patient with two comorbidities, on three meds, with an atypical presentation that only partially fits that triad.

If your brain has been trained to look for “perfect textbook pattern = diagnosis,” you underperform on vignettes that deliberately violate the perfect pattern. The modern exam does this constantly.

Qbank Data: The Elephant in the Room

Let’s talk about the resource that actually predicts performance: question banks and NBME practice exams.

Qbank companies love publishing internal “correlation” graphs between percentage correct and Step score. Ignore their marketing spin and look at the broad reality: performance on high-quality questions approximates performance on the real test more closely than anything you do with First Aid.

A student who sits at:

- 65–70% on UWorld + consistent NBME practice

- Uses First Aid only as quick reference / for memory anchors

routinely outperforms the student who:

- “Finishes” First Aid twice

- Does scattered questions without review or reflection

The mechanisms are obvious:

- Questions force active recall.

- They reveal your misconceptions.

- They train timing and triage.

- They create context for facts, which boosts retention.

First Aid does none of this by itself.

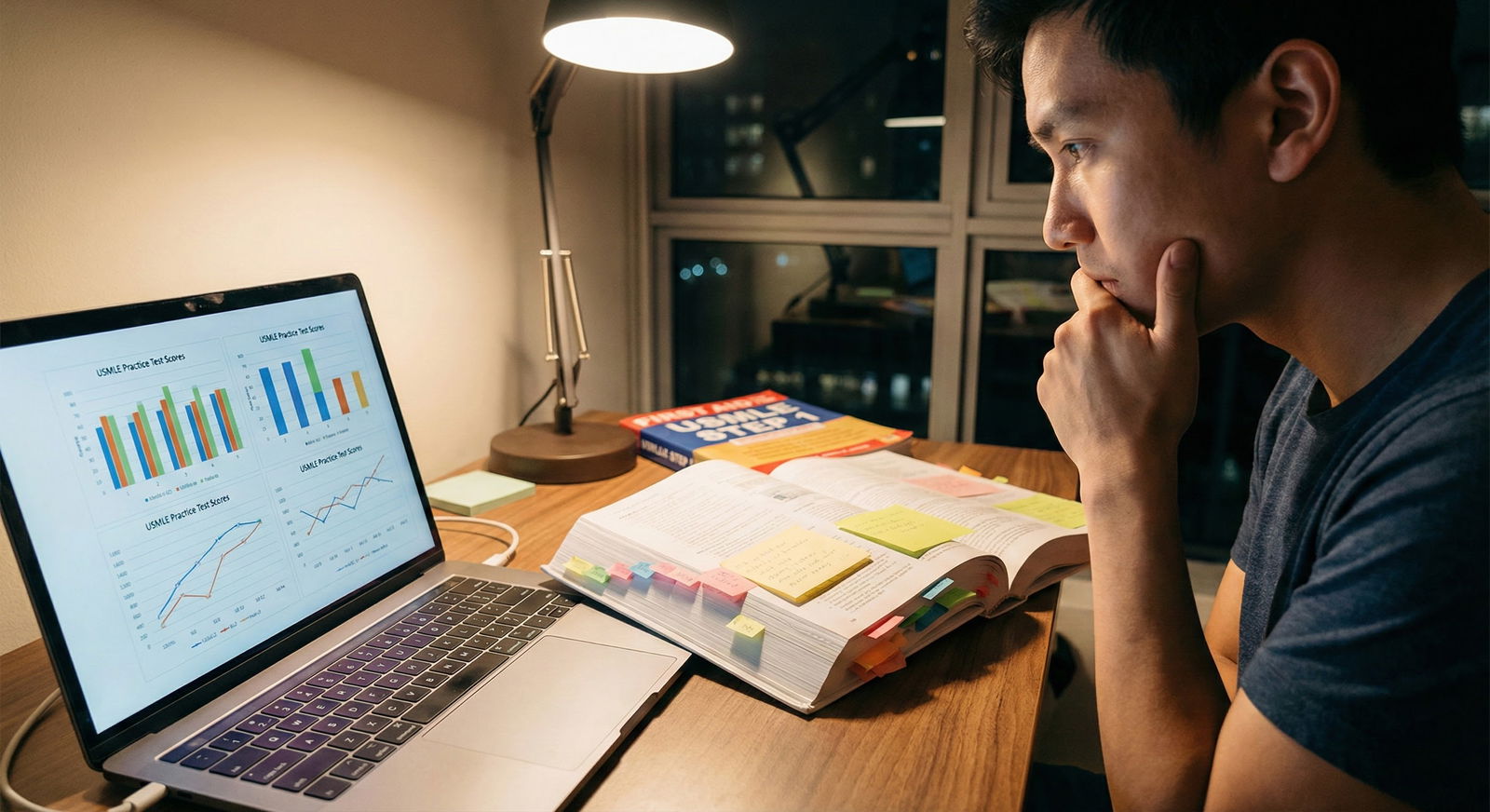

Here is what actually tends to separate “I passed” from “I crushed it” in real data from school learning analytics and student self-reports:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Qbanks | 40 |

| NBME Practice | 25 |

| Video/Conceptual Resources | 20 |

| First Aid Use | 10 |

| Random Extra Books | 5 |

These numbers aren’t exact, but they reflect how program directors, learning specialists, and plenty of high scorers intuitively rank what actually mattered. First Aid is a helper. Not the main driver.

The Illusion of Mastery: Why “Cover to Cover” Is Overrated

I’ve watched students proudly say, “I finished First Aid twice.” They’ll flip through pages covered in four colors of highlighting. Margins packed with tiny scribbles from every video they ever watched.

Then they sit down for an NBME and are shocked by a barely-pass score.

What happened?

Two problems.

Problem 1: Recognition vs. recall

Reading First Aid (even “actively”) mainly trains recognition. You see “Strep pyogenes → bacitracin sensitive” and think, yes, I know that. Feels good. But the exam doesn’t give you a two-column matching exercise. It gives you:

- A 32-year-old…

- With 4 days of symptoms…

- On this medication…

- With these lab values…

And asks for a mechanism, next step, or associated complication. Now you need recall and application. Very different skill.

Problem 2: Coverage ≠ proficiency

Seeing every page does not mean you can use the information quickly and flexibly.

This is why smart students burn hundreds of hours on “completing” First Aid and then discover their retrieval speed is glacial. On timed exams, slow recall might as well be no recall.

The commonly repeated advice “I read First Aid 4 times” is survivor bias plus nostalgia. Most of the people saying this also:

- Did enormous volumes of questions

- Used Pathoma/Boards & Beyond/SKetchy aggressively

- Went to schools that hammered them with NBME-style exams

They misattribute their score to the visible behavior (the book everyone sees) instead of the invisible grind (question-based learning, concept building, repetition under constraints).

Where First Aid Does Help (Used Correctly)

Now, I’m not saying burn it. That’d be stupid. The book has a clear role—just not the holy one people assign to it.

First Aid works well as:

- A scaffold: a way to organize and anchor details you learn more deeply elsewhere.

- A checklist: “Have I at least seen all the major bugs/drugs/diseases once?”

- A memory booster: mnemonics, quick associations, compact tables you revisit for spaced repetition.

- A reference: you miss a Qbank item on some obscure vasculitis, you look it up in First Aid for a concise summary.

Students who use it this way tend to have annotations that point back to practice questions and deeper resources, not pages bloated with everything under the sun.

In other words: First Aid becomes a map, not the territory.

Here’s the structural difference between treating First Aid as “Bible” versus “reference”:

| Approach | Typical Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Bible (primary text) | Good factual base, poor flexibility |

| Reference (supporting) | Better application, higher ceiling |

The Modern Exam and the “One Book” Fantasy

People clinging to a single-book strategy are usually working off stories from pre‑2010 Step 1 or from schools with extremely exam-aligned curricula.

But modern USMLE design intentionally resists one‑book coverage. The test-makers know you’re using commercial materials. They see the same resources you do. They design around them.

They emphasize:

- Novel clinical vignettes

- Integration with ethics, biostats, and communication

- Mechanism-based reasoning over orphan factoids

No single outline book, no matter how well edited, can keep up in real time with how vignettes are written and tweaked.

I’ve seen students walk out of Step 1 or Step 2 and say the same thing: “I recognized a lot of topics, but the way they were asked felt different from anything I’d memorized.”

Exactly. That’s the point.

A More Honest Study Strategy

If you’re in medical school right now, here’s the uncomfortable truth: the backbone of strong exam performance is doing hard questions, early and often, and learning from them deliberately.

First Aid plays a secondary role:

- After you miss a question on renal tubular acidosis, you use First Aid to solidify the classification and key features.

- After a block where you repeatedly botch murmur questions, you return to the cardiac section and tie your question experience to the summary tables.

- When you watch a pharm video series, you use First Aid tables as your condensed “final draft” of what to memorize.

What you don’t do—if you care about efficiency and actual performance—is treat page-count as progress.

To visualize how your time should actually look during dedicated vs what many students do:

| Category | Qbanks/NBMEs | Concept Resources | First Aid Review | Misc/Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effective Plan | 55 | 25 | 15 | 5 |

| First-Aid-Only Plan | 30 | 15 | 45 | 10 |

The “First-Aid-Only” bar is how a lot of anxious M2s actually live. It feels safer to “finish the book” than to confront your NBME score every week. But the data points the other way.

The Psychological Trap: Why This Myth Won’t Die

If the evidence against “First Aid as Bible” is this clear on the ground, why does the myth persist?

Two big reasons.

First, simplicity is seductive. “Just do X” is comforting. One book, clear finish line, easily shared advice for upperclassmen to pass down, no nuance required. Nobody wants to say, “You need an integrated approach, heavy question practice, and brutal honesty about your weak systems.”

Second, post hoc ego protection. Many people did, in fact, spend hundreds of hours with First Aid. They also did many other things. When they succeed, it’s easier to credit the thing they can point to physically than the ugly, humbling hours in question banks where they felt stupid. Memory is biased that way.

There’s also survivorship bias: the students who did First Aid‑heavy studying and then failed or barely passed don’t become loud online gurus. They disappear into silence or remediation. You don’t hear their version of “I memorized it and still got burned.”

I’ve heard that story. Many times. It doesn’t trend on Reddit.

A Quick Reality Check Framework

If you want an honest gauge of whether your First Aid usage is healthy or delusional, ask yourself three questions:

Can I consistently hit my target score range on timed NBME-style exams?

If no, “but I’ve read First Aid twice” is irrelevant.When I miss questions, do I understand why at a conceptual level?

If your post-hoc analysis is just “I didn’t memorize that fact,” you’re missing the bigger failure: weak reasoning.Could I pass if First Aid magically vanished tomorrow?

If the answer is no, you’ve built your house on an outline instead of on understanding and practice.

Students who eventually do very well can answer yes to at least the last question. They’ll be annoyed, but they won’t be helpless.

Step 2 and Beyond: The Myth Breaks Completely

If you somehow squeeze by Step 1 on brute-force First Aid memorization, that strategy collapses on Step 2 and the shelf exams.

Here, clinical vignettes dominate. Guidelines matter. Management decisions and diagnostic algorithms are front and center. There is no single equivalent of First Aid that can be hallucinated into a “Bible” without serious consequences.

Clerkship exams expose this rapidly:

- The student who only “studies from the outline book” but doesn’t grind questions gets eaten alive on medicine and surgery shelves.

- The student who uses UWorld, NBME forms, and targeted references (Uptodate, AMBOSS, etc.) outperforms, even with less “total reading time.”

USMLE Step 2 CK is even more unforgiving of shallow rote learning than Step 1. The sooner you unhook your brain from the “one book” fantasy, the better off you are for everything downstream: residency, boards, real practice.

So Where Does This Leave You?

Three takeaways, stripped of mythology:

First Aid is a useful outline, not a curriculum.

It’s good for organization and memory cues, but it doesn’t teach you to think the way modern exams demand.Qbanks and NBMEs drive performance, not page counts.

The most consistent predictor of real exam scores is how you perform on high-quality practice questions—not how many times you “finished” First Aid.Understanding and application beat memorization every single time.

The more you force yourself into hard, timed, integrated questions, and then repair your weak concepts, the less you’ll need to cling to any single “Bible” at all.

Use First Aid. Annotate it. Refer to it. Just stop worshipping it.