The way faculty talk about First Aid, UWorld, and Anki in front of you is not how they talk about it when you're not in the room.

You get the sanitized line: “Use multiple resources,” “Focus on understanding, not memorization.” Behind closed doors? They’re brutally clear about what actually works, what backfires, and which behaviors scream “this student doesn’t get it.”

Let me pull that curtain back for you.

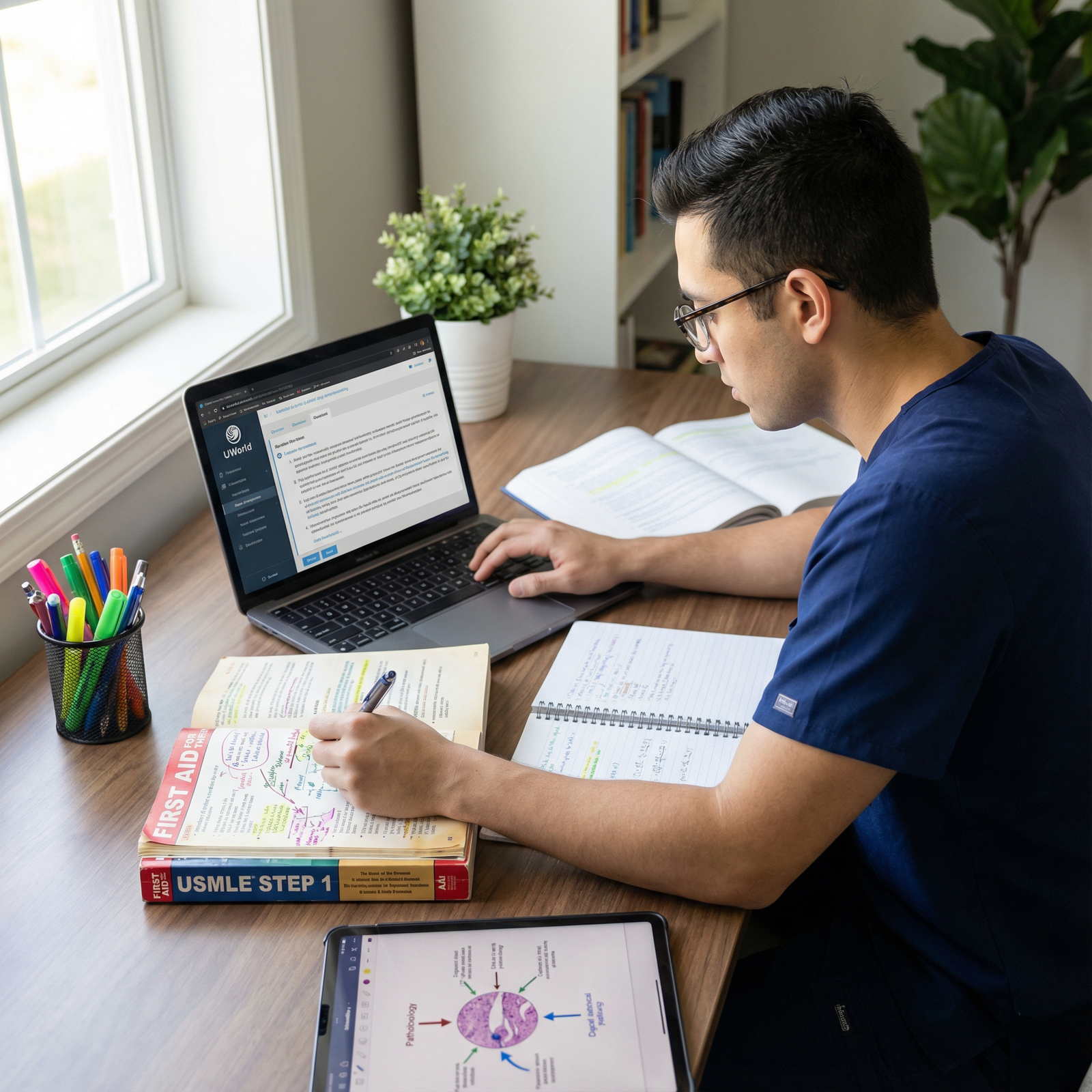

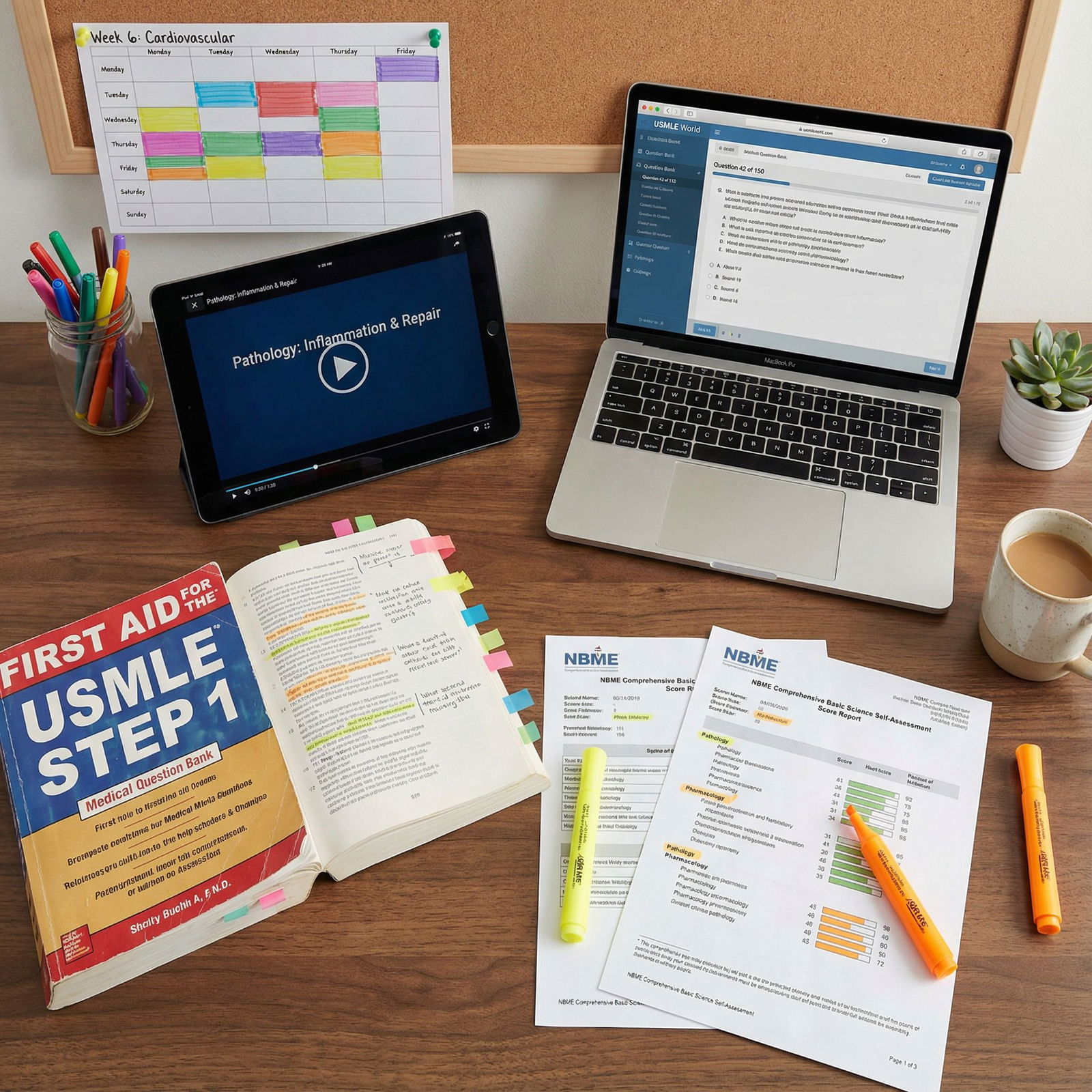

What They Really Think About First Aid

I’ve sat in those exam prep meetings where preclinical course directors, clerkship directors, and a couple of salty senior faculty review Step performance and try to “fix” the curriculum. First Aid always comes up. The public message is: “First Aid is a good high-yield review book but should not replace the curriculum.”

Behind doors, the commentary is sharper.

Here’s the unfiltered version of what many faculty actually say.

“First Aid is a map, not the territory.”

Neuro faculty hate—truly hate—when students only know the First Aid version of neurology. I’ve heard, verbatim: “I can tell which students live in First Aid. They know buzzwords. They don’t know medicine.” When someone on rounds spits out “subacute combined degeneration” but can’t explain why B12 deficiency hits dorsal columns and corticospinal tracts, the attending knows exactly what happened: wall-to-wall FA memorization with zero depth.They know you need it. They used their own version.

Older faculty used BRS, “blueprints,” Goljan, Kaplan books. First Aid is just the current avatar of that same idea: a compressed, exam-targeted outline. Most of them quietly accept that you need a synthesis resource. The better ones will even tell each other: “We should probably align our emphasis with what’s in First Aid, or at least not contradict it.” They will not say that into a microphone at orientation. But they adjust slide decks based on what they see in First Aid more than you realize.They watch for the “First Aid-only” student pattern.

When a student bombs an in-house exam and then claims, “But I went through First Aid twice,” the course director rolls their eyes and tells the committee: “Classic. They tried to shortcut the course using Step material.” Those students get labeled as “board-focused, low engagement,” and that reputation follows them into clerkships if you’re not careful.They actually check it when building exams.

Here’s the part no one tells you: some faculty literally keep a copy of First Aid (physical or PDF) open when writing questions—not to copy from it, but to make sure they’re not testing some obscure pet topic that isn’t anywhere in standard board prep material. Especially newer faculty who are terrified of being “that person” whose questions students complain about.

I’ve watched an attending say: “If it’s not in First Aid or a major review book, it probably shouldn’t be on our exam at the level we’re testing it.”

- They know First Aid is dangerous for early M1s.

When M1s show up with First Aid at the beginning of anatomy, most faculty see that as a red flag. Chair of anatomy, to me once: “They’re trying to memorize bullet points before they even understand the body. It always backfires.” The internal consensus? First Aid before you’ve had a real pass through the material turns you into a parrot, not a thinker. And parrots crash hard on conceptual questions.

So what’s the “whisper-level” advice on using First Aid?

Use it late and targeted. You earn the right to truly use First Aid once you already understand the story from lecture, path, and phys. Faculty who know how Step works quietly advise their mentees:

- First Aid is for consolidation, not discovery.

- It’s your index of what must not be missed, not your only textbook.

- If you cannot explain a bullet point out loud in your own words, you haven’t learned it—no matter how many color-coded highlights you’ve added.

UWorld: The Resource They Trust More Than You Think

Among seasoned faculty, there’s a very clear hierarchy: students who grind UWorld properly vs students who “save it” or dabble casually. They will never formally announce this, but in private, it’s almost a running joke.

I sat in one meeting where the associate dean literally said: “Show me a student who finished UWorld thoughtfully and I’ll show you a student who almost never scares me clinically.”

Let me break down the backroom take on UWorld.

Faculty quietly use UWorld as a barometer of seriousness.

When a struggling student meets with a learning specialist or director and says, “I didn’t really use UWorld. I was saving it,” the faculty conclusion is immediate: this student doesn’t understand how these exams work. They won’t say that out loud, but the trust level drops. You look like someone who’d go into the OR without checking the patient’s allergy list.Some attendings steal from UWorld to shape how they teach.

I’ve watched IM and surgery attendings flip through UWorld stems on their phone in the workroom and say: “See? This is exactly how they integrate renal + cardio + pharm. That’s how we should pimp.” They recognize that UWorld’s question writers are often better at weaving clinical reasoning than many lecture slides.

They’re not afraid of UWorld. They’re jealous of how efficient it is.

- They know you shouldn’t be getting high 50s forever.

Program directors who still keep an eye on Step data have a mental scale. They’re not memorizing your exact percentages, but they know the rough relationships.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| <50% | 205 |

| 50-59% | 215 |

| 60-69% | 225 |

| 70-79% | 240 |

| 80%+ | 250 |

They talk like this:

- “Most kids in the low 50s on UWorld with full pass-throughs end up low 220s.”

- “The ones sitting solidly in the mid-60s usually clear comfortably.”

If you’re living in 40–50% territory deep into your dedicated period, the ones who know boards will quietly panic for you even if they keep a calm face.

- They hate when you treat UWorld like a trivia machine.

What irritates them is not that you use UWorld—it’s how you use it. When a student rattles off that they’ve “done 5,000 questions” but can’t walk through a case logically, the whispers get harsh.

I’ve heard: “He’s memorized stems. He hasn’t learned medicine.”

What impresses them is when you can take a wrong question and reconstruct the whole pathophysiological chain, articulate the distractors, and then tie it to a real patient you saw. That’s the student they enjoy teaching.

- They know some of their own exams are worse than UWorld.

This one they never admit publicly. But over coffee: “Honestly, UWorld’s explanation is better than our entire lecture on that topic.” I’ve heard that exact sentence. More than once.

So, how do the insiders really think you should use it?

Start earlier than the official line says.

Not M1 day one, but you should not be opening your first block of serious UWorld questions two weeks before Step. The unspoken faculty expectation for a solid Step taker is: one full thoughtful pass, then targeted second-pass or another reputable Qbank.Do not “save” it.

That saving mentality? Faculty interpret it as magical thinking. A dean once said: “They think untouched UWorld questions are going to rescue them in the eleventh hour. It’s fantasy.”

UWorld is your training ground, not your secret weapon.

Anki: The Dirty Little Secret of Top Scorers

Here’s the real split: most older faculty do not get Anki at all. But the younger attendings, the senior residents, the chief residents? They know exactly what’s happening, and they watch you closely around it.

There are three parallel narratives about Anki in faculty rooms.

- The old guard: “These kids are flashcard addicts.”

A senior pathologist said to me: “They click cards for hours and then can’t describe a disease from beginning to end.” He’s not entirely wrong. They’ve seen students chained to their reviews to the point that they show up to small group already mentally fried from “doing cards since 5 a.m.”

To them, Anki looks like compulsive, joyless memorization.

The mid-career realists: “Spaced repetition works, but they overdo it.”

These are the clerkship directors who’ve read the literature on spaced repetition and see improved Step scores in the “Anki kids,” but also notice those same students sometimes flounder at the bedside. They might say in meetings: “We like the outcomes, but we’re worried they’re memorizing instead of reasoning.”The younger faculty/residents: “Anki is the game-changer—if you’re not a slave to it.”

The PGY-3 who crushed Step 1 and 2? They used Anki. Aggressively. But they also suspended their deck the night before call. They missed days when life demanded it. They adjusted. Those people are now the ones whispering to students in hallways:

“Stop chasing a 0-review pile. You’re not getting a medal for Anki streaks.”

I’ve literally heard a chief resident say to a struggling MS3: “You look burned out. Turn Anki off for three days. The cards will be there when you come back. Your hippocampus, maybe not.”

Where do faculty draw the line mentally?

- If you’re constantly glancing at your phone to “just clear a few more cards,” attendings notice. They see it as distraction, not discipline.

- If you can smoothly answer, “What’s the mechanism of this drug?” or “What are the side effects?” with clean, crisp recall—they know something is working in your background. They may not even know the word Anki, but they know flashcards are doing that work.

The unofficial, whispered advice from the people who both crushed boards and survived residency:

Use Anki as your memory scaffold, not your entire life.

New M1s and early M2s make three big Anki mistakes that faculty silently judge:

- Building monstrously detailed cards out of lecture slides that will never be tested.

- Refusing to delete or suspend useless cards because “my streak.”

- Treating missed reviews as a moral failure instead of a signal to trim the deck.

Faculty don’t care how many cards you do. They care if you remember what matters and can apply it to real humans without crumbling.

How Faculty Connect These Three Resources in Their Heads

Here’s the part you rarely see: how faculty mentally combine First Aid, UWorld, and Anki when they think about you as a learner.

In a curriculum redesign session I sat through, a younger faculty member drew a triangle on the board and labeled it exactly like this:

- One corner: “CONTENT MAP (First Aid-level)”

- Second corner: “REASONING + CLINICAL APPLICATION (UWorld-style cases)”

- Third corner: “RECALL ENGINE (spaced repetition / Anki)”

Then she said: “Every strong board score I’ve seen is someone who hit all three.”

That’s basically the hidden consensus:

- First Aid: defines the scope of what any sane student should know.

- UWorld: defines the style of thinking the exam demands.

- Anki: maintains the density of facts in your head without constant relearning.

What they whisper, but do not put in official handouts, sounds like this:

- “Our top 10% Step takers almost all used some combination of FA + UWorld + spaced repetition, whether or not they call it Anki.”

- “The kids who swear they’re ‘doing fine without questions’ scare me the most.”

- “The ones who brag about never using First Aid usually either already know it from somewhere else or are kidding themselves.”

They don’t care which add-ons you use—Boards & Beyond, Pathoma, Sketchy, whatever. Those are style choices. But if you’re skipping any one of those three structural pillars, they quietly lower their expectations for your boards and sometimes for your clinical performance.

What Impresses Faculty (And What Makes Them Roll Their Eyes)

Let me be very concrete, because this is what you actually need.

Faculty are quietly impressed when:

You use First Aid to organize your understanding, not hide from it. On rounds: “So this fits with what we learned about nephrotic vs nephritic in First Aid, but in this patient, the key was the selective albumin loss, which made me think minimal change.” That tells them you integrated board knowledge with real life.

You talk about UWorld in terms of lessons, not numbers. “I missed a bunch of SIADH questions until I realized I was ignoring urine osms and sodium—now I’m always checking those.” That sounds like growth, not grind.

You treat Anki as supporting infrastructure. “I keep cards for mechanisms, side effects, and classic presentations but I don’t bother with trivia. If I keep missing a card and it’s low-yield, I just suspend it.” To an insider, that’s the sound of someone who will still be sane in residency.

They quietly roll their eyes when:

You say, “I’m on my third pass of First Aid” but cannot explain a basic concept without reciting bullet points. That screams cosmetic studying.

You proudly admit, “I haven’t really done UWorld, I’m saving it for dedicated.” To them, that’s like saving your first intubation attempt for a crashing patient.

You spend every free second on Anki during rotations, to the point that your notes suck and your patient presentations are weak. Residents will tear you apart behind closed doors for that—they see it as self-absorbed and clinically tone-deaf.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Student uses FA, UWorld, Anki |

| Step 2 | Integrated understanding |

| Step 3 | Overfocused on one tool |

| Step 4 | Strong boards + solid clinical skills |

| Step 5 | High anxiety, patchy performance |

| Step 6 | Balanced? |

The Quiet Patterns They See Every Year

After a few cohorts, faculty stop looking at individual students and start seeing patterns. Here are three archetypes they talk about off the record.

1. The “Outline Zombie”

Lives in First Aid and Anki. Avoids questions because “I’m not ready yet.” Gets good at definitions, terrible at decisions. Boards: barely average, despite spending 60+ hours a week “studying.” On rotations, they know every cause of elevated LFTs but cannot prioritize what to actually order or do.

Faculty comment: “Works hard, poor test strategy, zero clinical instincts early on.”

2. The “Question Grinder Without a Spine”

Crushes 80 questions a day. Barely reviews them. Panics about percentages constantly. Hates content review because it “feels slow.” Trusts UWorld more than any teacher, more than any textbook, more than their own thought process.

Boards: often decent, sometimes surprisingly mediocre. Clinically, they can parrot UWorld stems but get lost when the patient does not fit the mold.

Faculty comment: “Knows a lot of fragments. Needs guided reflection to put it together.”

3. The “Quiet Killer”

This is who program directors fall in love with.

They use First Aid, but you almost never see it open in public—it’s their private checklist. They do UWorld early, even if they get destroyed at first, and they review each question like it mattered. They use Anki or some spaced repetition system, but they’re totally willing to miss a day if they’re post-call, or if a real patient needs extra time.

Boards: strong. Maybe not always 260+, but reliably above expectations. On wards, they connect dots. They ask questions that show synthesis, not panic.

Faculty comment: “This one’s going to be fine. In any specialty.”

| Category | First Aid / Content | UWorld / Questions | Anki / Spaced Repetition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preclinical | 40 | 30 | 30 |

| Dedicated Period | 30 | 50 | 20 |

| Clerkships | 15 | 35 | 10 |

How To Align With What Faculty Actually Respect

You’re not trying to impress them for fun. You’re trying to not sabotage yourself by following the wrong signals.

If you want to align with what they quietly respect:

Use First Aid as your synthesis anchor, not your daily bible in M1. Bring it in hard once you’ve had at least one pass through the content, especially late M2 and dedicated.

Treat UWorld as non-negotiable core training, not a luxury add-on. Start chunking it in during organ systems. Live in the explanations. Don’t fear low percentages at the beginning; fear shallow review.

Let Anki be your memory maintenance, not your personality. If your card count starts to choke out your life, your sleep, and your ability to engage with real people, you have crossed the line where it helps.

The phrase I’ve heard from good faculty more than once is: “I want them to use tools. I don’t want the tools to use them.”

Years from now, you won’t brag about how many cards you reviewed or how many passes of First Aid you completed. You’ll remember the patients whose care you actually improved because you understood what was happening. These resources are bridges to that point—not destinations.

FAQ

1. Do faculty actually care which specific resources I use, or just my performance?

Publicly, they’ll say they care only about your performance. Privately, many do care how you got there, because your study habits predict how you’ll behave as a resident. Someone who achieves a good Step score by thoughtful questions, spaced repetition, and integrated studying feels safer to them than someone who brute-forced 16 hours a day of memorization. That said, they’re not tracking whether you use Boards & Beyond vs Sketchy—they’re noticing whether you use some combination of structured content, questions, and recall.

2. Is it a problem to start First Aid or UWorld in M1?

It’s not inherently a problem, but this is where faculty shake their heads a lot. First Aid in early M1 is usually noise—you do not have the framework to make those bullet points meaningful. UWorld in very early M1 will crush your confidence unless you treat it as exposure, not as a score. Most insiders would tell you: build foundations with your courses first, then layer in FA and questions by system once you have some grounding.

3. What do attendings think if I’m doing Anki on my phone during downtime on rotations?

They notice. Constantly being on your phone looks bad unless the culture on that team is explicitly lax and you’ve built trust already. If you’re always “just clearing cards” while others are reviewing labs, imaging, or reading about their patients, residents will absolutely talk about it when you’re not there. The safe rule: patient chart > primary literature/UpToDate > teaching > then Anki. Never reverse that order.

4. How do I know if I’m over-relying on one of these tools?

Look at your weaknesses. If you know tons of facts but bomb multi-step questions, you’re leaning too hard on Anki/First Aid and skimping on UWorld-style reasoning. If you crush UWorld but forget basic mechanisms a week later, your recall system is weak. If you’ve read First Aid three times but can’t connect organ systems, you’re using it like a script, not a map. When faculty see that mismatch—strong in one dimension, glaringly weak in another—they instantly suspect a lopsided resource strategy.