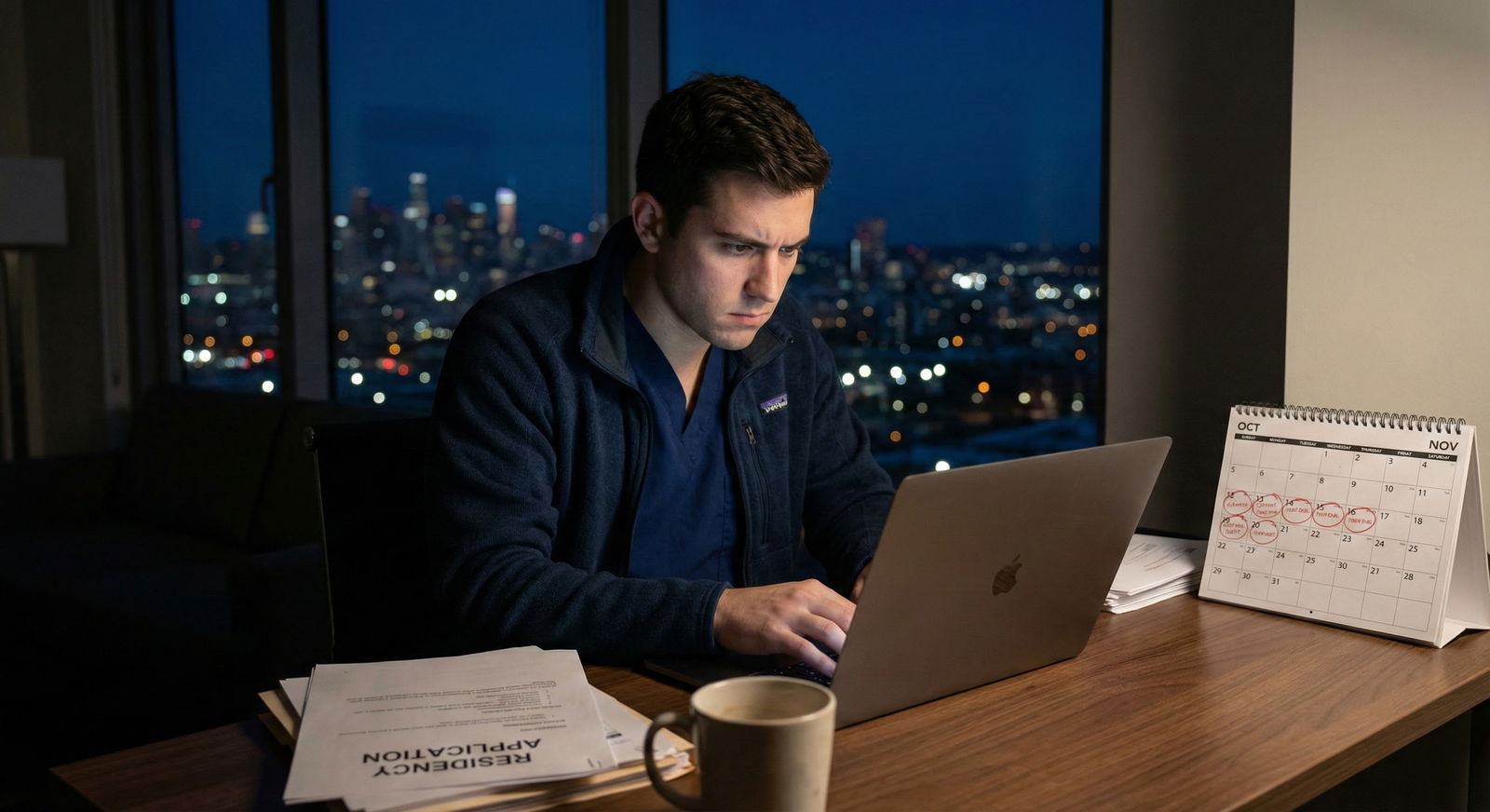

It’s August. Your ERAS account is open in one browser tab. In the other, you’ve got the half-finished research project / startup / global health thing that was supposed to “change your application.”

Your mentor says, “If you can get that manuscript submitted, it’ll really help.”

Your co-resident friend says, “Just apply. PDs care way less than you think.”

You’re stuck on the question:

Do I delay my application to finish this gap year project, or apply now with what I have?

Here’s the straight answer:

Most people overestimate how much one more project will change their chances and underestimate the cost of delaying a whole application cycle. But there are situations where waiting is absolutely the right move.

Let’s walk through when to wait, when to apply, and how to decide in under an hour instead of spiraling for three months.

Step 1: What Are You Actually Trying to Fix?

You don’t delay an application “just because.” You delay to fix something specific and material.

Break your situation into four buckets:

| Component | Level of Control Now | Can Improve in 6–12 Months? |

|---|---|---|

| Exams (USMLE/COMLEX) | Low (scores are set) | Only if you haven't taken Step 2 yet |

| Clinical Performance (clerkship grades, MSPE) | Fixed | No |

| Experiences (research, leadership, projects) | Medium | Yes |

| Narrative (personal statement, letters, story) | High | Yes |

The key question:

Is the project you’re considering delaying for fixing a fatal weakness, or just polishing an already viable application?

If you don’t have at least one clearly problematic area, delaying is usually a bad trade.

Typical “fixable” problems where a delay might matter:

- You haven’t taken Step 2 yet and need a strong score to offset a weak Step 1 or COMLEX Level 1.

- You have almost no specialty-relevant experience for a competitive field (e.g., applying ortho with zero ortho research/rotations).

- You’re switching specialties and have nothing yet that shows commitment to the new field.

- You completely lack letters from the specialty you’re applying into, and your planned project solves that.

If your main issue is “my CV isn’t as shiny as other people’s,” that’s not a strong reason to lose a whole year.

Step 2: How Much Will This Gap Year Project Actually Move the Needle?

Let me be blunt:

Finishing a gap year project rarely transforms an otherwise weak application into a strong one. It usually moves you from “solid” to “a bit stronger.”

Programs don’t rank:

- “Completed RCT with first-author NEJM paper”

vs. - “Not quite finished case report”

They rank:

- Scores

- Performance on rotations

- Letters

- Interview performance

- Overall story and professionalism

So, ask three hard questions about your project:

What will it realistically be by application time?

- Already accepted paper?

- Submitted?

- “Manuscript in progress?”

- “Ongoing project?”

Who is attached to it?

- Well-known name in your specialty who will write you a strong letter?

- Or a nice but unknown attending at a community site?

Does it fix a specific problem or just add bulk?

- Problem-fixing: Your only psych letter, your only US clinical experience, or your only derm research for derm.

- Bulk: Your fourth basic science poster that no one will read.

For context:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| USMLE/COMLEX | 9 |

| Clinical performance | 8 |

| Letters | 8 |

| Specialty fit/experiences | 7 |

| Research output alone | 3 |

Research or a project by itself is rarely what saves an application—unless we’re talking about hyper-competitive specialties where everyone is already maxed on scores and grades.

Step 3: When You Should Delay a Cycle

Here are situations where I’d seriously tell someone: “Yes, you should probably wait.”

1. You Haven’t Taken Step 2 (and You Need It to Rescue Step 1)

If:

- You have a low Step 1 (or just “Pass”) AND

- You’re getting consistent practice scores that suggest Step 2 will be clearly stronger

Then delaying to get a strong Step 2 on your application can be a game changer, especially for:

- IM, EM, Gen Surg, Neuro, etc.

- Coming back from a fail attempt

- Applying as an IMG needing to prove test strength

Here, the “project” isn’t the gap year activity itself. It’s the score.

2. You’re Switching Specialties Without Any Proof

Example: you did two years of research in neurosurgery, but now you want IM. Right now you have:

- No IM letters

- No IM sub-I

- No IM-focused personal statement

- No IM-related activities

If your gap-year project is:

- An IM-based clinical year

- Hospitalist research with a known IM attending

- Or anything that gives you strong IM letters and a coherent story

Then yes, delaying can absolutely rescue your credibility.

3. You Currently Have Zero or One Weak Letter in Your Target Specialty

Derm without derm letters. Ortho without ortho letters. Psych without psych letters. That’s suicide in some fields.

If your gap-year project guarantees:

- Daily contact with a specialty faculty member

- Real responsibility and observed work

- And they’ve already hinted they’d write you a strong letter

Then delaying so that letter is ready and authentic? Reasonable.

4. You’re an IMG or Non-Traditional Applicant Without US Clinical Experience

If you’re planning to use a gap-year research or clinical job to:

- Get US letters

- Get US systems exposure

- Show that you can function in a US hospital

That’s materially important. For many IMGs, this is the difference between no interviews and some interviews.

Step 4: When You Should Not Delay

Now the more common scenario: someone wants to delay for reasons that sound good but are actually weak.

I’d tell you not to delay if:

Your scores and core metrics are already in range for your target specialty.

Example: Step 2 in the 230s–240s aiming for IM or 220s+ aiming for FM/psych/peds, decent clinical performance, at least one relevant letter. Don’t lose a year to add one more bullet point.Your gap year project is speculative.

“We might submit this to JAMA.”

Translation: could be nowhere near done by application season.Your motivation is mostly fear or comparison.

“Everyone on Reddit has 12 publications.”

Half of those posts are fake or cherry-picked. Residency PDs aren’t reading your PubMed page like a Step score.You already have some research/activities and they’re fine.

Going from 2 posters + 1 paper to 4 posters + 2 papers doesn’t move you from “rejected” to “star.” It moves you from “fine” to “slightly more impressive.”You don’t have a clear plan for the extra year.

“I’ll kind of work on research and maybe moonlight and travel.”

Programs aren’t impressed by vague “time off.” A gap year needs a clean, defensible story.

Step 5: A Simple Decision Framework

Use this like a quick diagnostic algorithm.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Thinking of delaying application |

| Step 2 | Apply this cycle |

| Step 3 | Leaning: Apply now |

| Step 4 | Leaning: Reasonable to delay |

| Step 5 | Do you have a clear, fixable weakness? |

| Step 6 | Will project directly fix it by application time? |

| Step 7 | Is the project guaranteed or highly likely to complete? |

| Step 8 | Is the specialty competitive or your situation high-risk? |

“Clear, fixable weakness” means things like:

- No specialty letters

- No US clinical experience (for IMGs)

- No proof of commitment to a very competitive field

- Very low score that can be realistically rescued by Step 2

If you walk that flowchart honestly, you’ll usually end up with the right answer in 5 minutes.

Step 6: Hidden Costs of Delaying a Year (That People Forget)

People talk a lot about “strengthening the application.” They don’t talk enough about opportunity cost.

Here’s what you pay when you delay:

- One year of attending salary, pushed back. For many specialties, that’s $200–400k. Compounded over a career, that’s not small.

- Risk that the match landscape gets worse. New schools. More grads. Changing visa rules. You don’t control any of that.

- Risk of burnout / loss of momentum. I’ve watched people drift during gap years, then end up with a weaker story, not a stronger one.

- Emotional toll. Watching your classmates match while you sit on the sidelines again isn’t nothing. It hits harder than you think.

Are there times when that cost is worth it? Yes. If you’re currently a long shot for your desired specialty, or you’re fixing a true red flag, buying another year can be smart.

But “I’d like one more poster” rarely beats the cost of a lost year.

Step 7: How to Handle an “Incomplete” Project If You Apply Now

Let’s say you follow the logic and decide not to delay. What do you do with the half-baked project?

A few tactical points:

List it honestly.

Use “ongoing,” “in progress,” “submitted,” “provisional acceptance,” etc. Don’t lie or fluff.Leverage the experience, not just the outcome.

Programs care that you learned how to work on a team, handle data, think about patient care, or see a project through. Frame it that way in your descriptions and interviews.Use updates only if they’re real upgrades.

If mid-season your project gets accepted at a real journal or major conference, some programs (especially smaller ones) do pay attention to applicant updates. But don’t spam low-impact updates.Make sure it still feeds your story.

Even unfinished, a project that clearly aligns with your specialty interest still helps you sound coherent on interview day.

Step 8: If You Do Decide to Delay – Make the Year Bulletproof

If you’ve thought it through and delaying is the right move, don’t half-commit. A “soft” gap year looks terrible.

Your year should:

- Have a primary identity: “research fellow in cardiology,” “hospital-based clinical fellow in psych,” “full-time quality improvement coordinator in EM.”

- Generate specific outcomes: at least one strong letter, concrete contributions you can talk about, maybe a paper or abstract, but definitely tangible work.

- Include continued clinical exposure if possible: moonlighting, per-diem work, scribing, clinical research with direct patient contact. Keeps you sharp and credible.

And you should be able to explain it in one clean sentence next year:

“I took a structured research year in cardiology to deepen my clinical research skills and ended up working on three outcomes studies and co-authoring a paper, plus I got to work closely with my current letter writer.”

If your sentence is:

“I just needed some time and did some stuff and traveled a bit and…,” that’s not a good look.

Quick Reality Check by Specialty

Not all fields treat “extra projects” the same way.

| Specialty Type | Extra Project Impact | Delay More Often Worth It? |

|---|---|---|

| Hyper-competitive (Derm, Ortho, Plastics, ENT) | Moderate–High | Sometimes |

| Competitive (Gen Surg, EM, Neuro, Rad, Anes) | Moderate | Case-by-case |

| Less competitive (FM, Psych, Peds, Path) | Low–Moderate | Rarely |

If you’re aiming for derm with a 230 Step 2 and no derm research, yeah, a derm research year might be your ticket.

If you’re aiming for FM with decent scores and some clinical experience, delaying for one more QI project is almost never the smart move.

FAQs

1. Will a first-author paper from my gap year significantly boost my chances?

It depends where you’re starting from. If you already have:

- Reasonable scores

- At least one solid letter in your specialty

- Some basic scholarly activity

Then one more paper—even first-author—moves you a bit, not a lot. It can help more in research-heavy fields (academic IM, some surgical subspecialties, radiation oncology) and highly competitive specialties where everyone has research. But it rarely converts a low-probability application into a high-probability one on its own.

2. I’m an IMG with average scores. Should I delay to get US research or observerships?

For IMGs, this is one of the most legitimate reasons to wait a year. US clinical experience and US letters are heavily weighted. A structured research or clinical year in the US with strong letters often matters more than another test point or extra home-country project. If your current application has no US exposure at all, delaying to fix that can absolutely be worth it.

3. My project will only be “in progress” by application time. Is that still valuable?

Yes, but modestly. Programs understand that projects take time. An “ongoing” or “submitted” project still shows initiative and specialty interest. The catch: it’s not usually powerful enough to justify delaying a full cycle just so you can list it. If it’s your main reason to delay, I’d lean toward applying now unless it’s tightly tied to a crucial letter or a specialty switch.

4. What if I apply now and don’t match—will that hurt me next year?

Being a reapplicant is a minor negative, but not a death sentence. The bigger issue is how you use the year between cycles. If you:

- Reflect clearly on what went wrong

- Add targeted improvements (better Step 2, more clinical exposure, stronger letters)

- Present a focused, upgraded application

You can absolutely match on the second try. In fact, in some cases, it’s smarter to take your shot now and, if needed, use next year as your “fixing year” with more concrete data about where the application fell short.

5. How do I get honest feedback about whether I should delay?

Don’t crowdsource this purely from Reddit or classmates. Do three things:

- Sit down with a specialty advisor or PD-level person who actually reads applications in your field.

- Bring your full CV, score report, and a realistic description of your gap year project and timeline.

- Ask them directly: “If I applied with this profile this year, what tier of programs would likely interview me? Would this specific project, completed, move me to a different tier?”

If the answer is, “You’d already be fine at most mid-tier programs,” you probably shouldn’t delay. If the answer is, “Right now you’re very unlikely to match in this specialty, but this year could change that,” then waiting is on the table.

Bottom line:

- Delay a cycle only if your gap year project will clearly fix a concrete weakness—scores, letters, specialty proof, or US experience—not just add another line to an already decent CV.

- The cost of losing a year is real: money, momentum, and mental health. Don’t trade that away for marginal gains.

- If you do delay, make the year unmistakably purposeful, with a clean story and tangible outcomes—not a vague “time off to work on stuff.”