The biggest myth about letters of recommendation is that great students automatically get great letters. They do not. Great planners do.

You are not trying to “find someone who writes good letters.” You are trying to turn a rushed, distracted attending into a specific, detailed advocate for you. That is a different skill. And it is absolutely learnable.

Here is the playbook: three intentional meetings, each with a clear objective, that convert a generic “happy to help” attending into the person who writes the letter that gets committees to stop skimming and actually read.

The Core Idea: You Are Managing a Mini-Project

Let me be blunt. Most attendings:

- Write letters at 10 p.m. after clinic.

- Reuse old templates.

- Forget half the things you did.

- Default to “hardworking, pleasant, team player” because they cannot recall specifics.

They are not malicious. They are overloaded.

Your job is to run this like a project:

Meeting 1 – Positioning

Turn yourself from “random student on my team” into “student I will invest in.”Meeting 2 – Evidence collection

Make it effortless for the attending to remember concrete examples.Meeting 3 – Letter trigger

Ask for the letter in a way that almost forces specificity and makes it easy to say yes.

You are not manipulating. You are removing friction for someone who is already inclined to help you, and you are giving them the raw material to write an honest, strong letter.

Let’s break the three meetings down.

Meeting 1: Position Yourself as “Letter-Worthy”

Timing: Within the first 3–5 days of working with the attending (earlier is better).

Goal: Put “I may write this student a letter” in the attending’s head while they can still observe you.

This is where most students blow it. They wait until the last week or, worse, months later by email. At that point the attending has no reason to have paid close attention to you.

Step 1: Set up a short, formal check-in

Ask something like:

“Dr. Smith, could I have 10 minutes sometime this week for feedback on how I am doing and how I can improve? I am trying to grow a lot on this rotation.”

Busy attendings understand “short, specific time block.” Do not say “whenever you have time.” Offer options:

“I am free after rounds at 11:30 or at 4:30 before sign-out. Whatever works best for you.”

Step 2: Use a simple agenda

In that meeting, you want to:

- Signal long-term goals.

- Get actual feedback.

- Plant the seed about letters without asking yet.

Script this roughly:

Open with purpose

“Thanks for making time. I want to make the most of this rotation. I am aiming for [field, if you know it] and I know strong clinical skills and letters from attendings who really worked with me are key. I wanted your feedback early so I can actually improve while I am here.”

That line tells them two things:

- You care about performance, not just grades.

- Letters are already on your mind.

Ask targeted questions

Not: “How am I doing?”

Instead:- “On rounds, what is one thing I could do this week to present more like an intern?”

- “On the wards, where do you see the biggest gap between me and a strong sub-intern level student?”

- “If I want to be in the top group of students you have worked with, what would that actually look like day-to-day?”

This forces them to picture “top student” vs “average student.” You want to be slotted into that mental category.

Respond like someone who will implement

If they say: “Your presentations are thorough but a bit disorganized.”

You answer:

“That makes sense. I will focus on tighter assessment and plan sections and try to prioritize the top problems first. Would it be okay if I check in with you next week to see if you notice improvement?”

Now they know you will circle back. Which sets up Meeting 2.

Soft letter seed

Close with something like:

“Down the line I will be asking a small number of attendings who saw me closely for letters for [med school / residency / post-bacc]. If I can reach the level you just described, I am hoping you might be someone I could approach. For now, I really appreciate your feedback and I will work on those specific points.”

You did not ask for a letter now. You just told them you will earn that ask. That difference matters.

Between Meeting 1 and 2: Earn the Right To Ask

Now you actually have to perform.

Focus ruthlessly on the items they flagged:

- If they mentioned presentations → practice with a co-student or resident before rounds.

- If they mentioned knowledge gaps → read UpToDate or a good review resource on the exact conditions you are seeing.

- If they mentioned ownership → be the person who knows the patient’s overnight events before being asked, pages the consults, follows up on labs without prompting.

You want them to say in Meeting 2: “Yes, I see a clear improvement.”

Because improvement is gold in letters. Committees love sentences like:

“Over the course of the rotation, I saw her go from hesitant to leading patient care discussions confidently, particularly on complex cases such as…”

That line only exists if you engineered it.

Meeting 2: Feed Them Specific, Memorable Material

Timing: 7–10 days after Meeting 1, while you are still on service with them.

Goal: Demonstrate growth, capture concrete stories, and gently preview the letter content.

Set it up similar to Meeting 1:

“Dr. Smith, could I grab another short feedback check-in? I tried to implement what you suggested about [presentations/ownership/etc.] and would value your perspective on whether you see improvement.”

Structure of the conversation

Quick recap of their prior advice

“Last time you mentioned I should tighten my assessment and better prioritize problems. I have been trying to structure my notes and presentations with a clearer top three issues and shorter bullet plans. Have you noticed a difference, or is there something I am still missing?”

This reminds them:

- They gave you advice.

- You listened.

- You changed behavior.

Let them comment on improvement

If they say, “Yes, much better,” push once more for specifics:

“That is helpful. Could you think of a moment this week where you saw me doing it better or closer to intern level?”

You are fishing for stories. Stories are what make letters pop.

Example: “Your presentation on the new CHF admission yesterday was very clear, and you identified the need for early cardiology involvement on your own.”

That is exactly the type of thing that ends up in a strong letter.

Steer toward key letter themes

Committees care about a few consistent buckets:

- Clinical reasoning

- Work ethic / reliability

- Communication with patients and team

- Teachability / receptiveness to feedback

- Professionalism

You can probe lightly:

- “From your vantage point, are there specific strengths you have noticed—for instance in my clinical reasoning or communication with patients—that I should continue to develop?”

- “Are there any concerns or weaknesses you would want me to work on before starting residency / med school?”

If they list strengths, mentally bookmark the phrases. If they list concerns, that is your chance to address them now, not have them silently appear in a tepid letter.

Set up the letter ask indirectly

At the end:

“I really appreciate your honesty. Feedback like this is exactly what I need. Toward the end of the rotation I am planning to ask a small number of attendings who supervised me closely for recommendation letters. Given you have now seen both my starting point and my progress, your perspective would be especially valuable for schools. I will circle back near the end if that is alright.”

You are not actually asking yet. But by now, they are expecting it. That is the point.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| First Days | 1 |

| Week 2 | 2 |

| Last Week | 3 |

Meeting 3: Convert Goodwill into a Detailed Letter

Timing: Last week of working with them, ideally when they have just seen you handle something well (case, presentation, procedure).

Goal: Get a clear yes for a strong letter and provide the exact scaffolding for a detailed, specific narrative.

Step 1: Ask the right yes/no question

Wrong version (common student mistake):

“Could you write me a letter of recommendation?”

Busy, conflict-averse attendings will almost always say yes, even if it is going to be mediocre.

Better version:

“Dr. Smith, based on what you have seen of my performance and growth on this rotation, would you feel comfortable writing me a strong, detailed letter of recommendation for [purpose: medical school / residency / post-bacc]?”

The extra words “strong, detailed” give them an exit if they cannot honestly say yes. If they hesitate, you just dodged a bland letter. That is a win.

If they say yes, then you move to logistics.

Step 2: Make it impossible for them to write a generic letter

After the yes:

“Thank you, that means a lot to me. To make your life easier, I can send you a concise packet with:

- My CV

- A short paragraph on my career goals

- A 1-page summary of specific cases and examples from this rotation that might be helpful to include

Would that be useful, and is there anything else you would like me to include?”

Most will say yes. Because they are tired.

Now you owe them something actually usable.

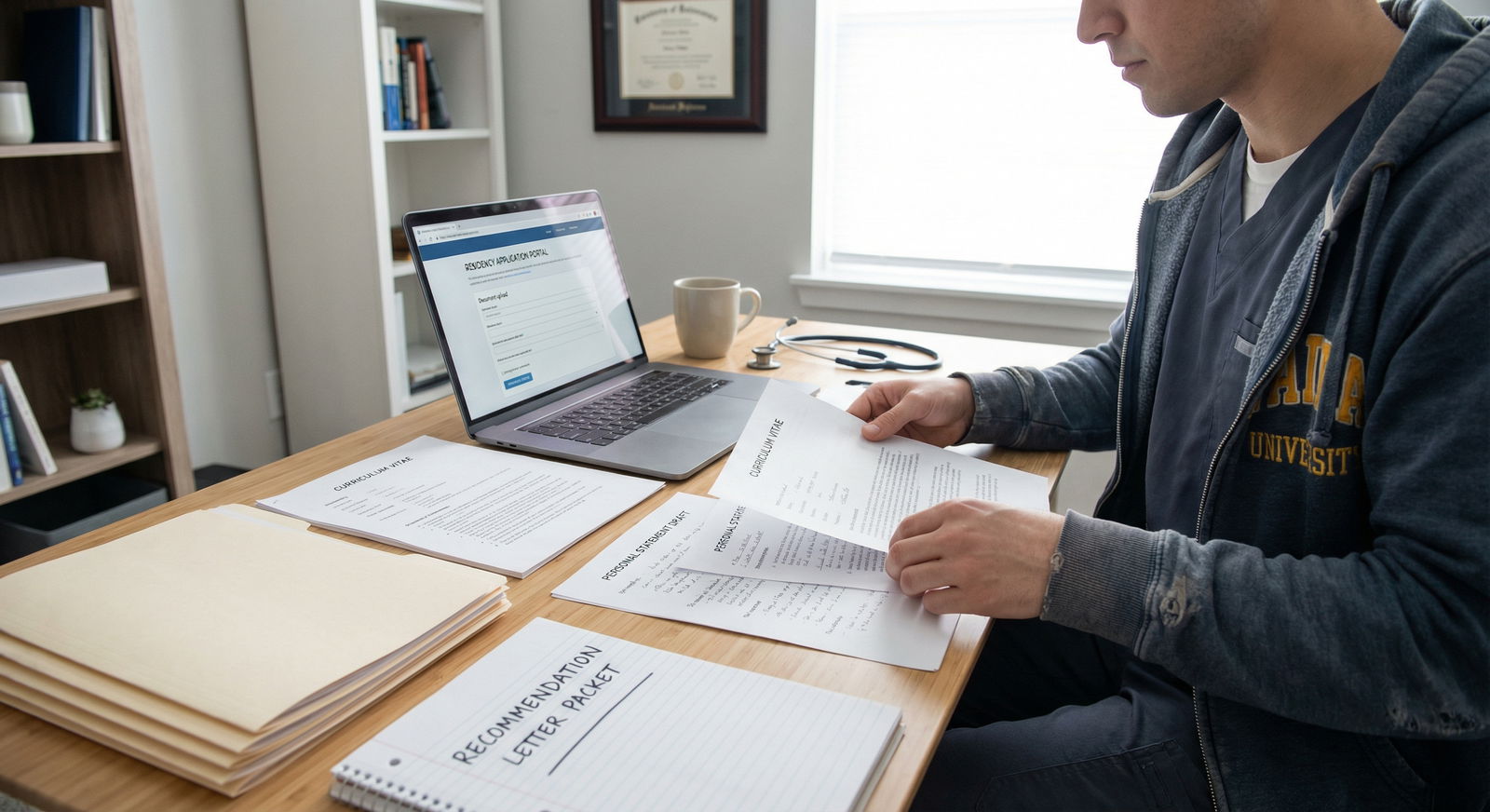

The “Letter Writer Packet” – Your Secret Weapon

This is where you turn “strong” into “specific, credible, and memorable.”

Your packet should be:

- 1–2 pages max, plus CV.

- Skimmable.

- Full of concrete, verifiable examples that match how they saw you work.

Core components

Header with your info

- Full name

- Contact info

- Application target (e.g., “Applying to U.S. MD programs, 2025 cycle”)

- Intended specialty or area of interest (if known)

3–4 bullet “themes” with supporting examples

Format it like this (and keep it tight):

1. Clinical reasoning and ownership

- “On 11/10, I presented Ms. R., a new CHF admission, including a differential for acute decompensation and proposed early cardiology involvement, which we implemented.”

- “Frequently volunteered to follow up on labs and imaging before rounds and update the team.”

2. Communication and professionalism

- “Led multiple family updates on patients with complex plans (e.g., Mr. T. in room 412 with new metastatic cancer diagnosis) with you or the resident present.”

- “Received unsolicited positive feedback from nurses about responsiveness to pages and clarity of orders.”

3. Teachability and improvement

- “After feedback to tighten presentations, redesigned my note and oral presentation, which you commented had improved by the second week.”

- “Actively sought mid-rotation feedback and implemented suggestions regarding prioritization of problem lists.”

You are not putting words in their mouth. You are reminding them what they saw, and offering the phrases and details they can adapt.

Short paragraph on goals

Example:

“I am applying to medical school with the long-term goal of working in internal medicine with a focus on underserved populations. I hope letters from attendings like you will highlight my clinical reasoning, work ethic, and capacity to grow quickly when given feedback.”

That gives them framing for the tone.

CV

Keep it clean and relevant. Do not make them dig through 6 pages of high school activities.

How This Looks in Real Life: From Vague to Sharp

Let me show you the difference you are engineering.

Generic attending letter (what you get without this system):

“I had the pleasure of working with Alex on our inpatient service for four weeks. Alex was punctual, hardworking, and well liked by peers and staff. He was eager to learn and took good care of patients. I believe he will make a fine medical student and I recommend him for your program.”

Nobody on an admissions committee remembers this. It could be about anyone.

Letter after your three meetings + packet (what you are aiming for):

“I worked closely with Alex for four weeks on our inpatient internal medicine service, where I directly observed his clinical reasoning, growth, and professionalism. Early in the rotation, Alex’s presentations were thorough but lacked prioritization. After we discussed this in a feedback meeting during his first week, I saw him rapidly reorganize his approach. By the second week, he was delivering concise, intern-level presentations, such as his discussion of a new CHF admission on 11/10 where he independently identified the need for early cardiology involvement.

Alex consistently demonstrated ownership of his patients. He routinely arrived early to review overnight events, often updated families himself (with appropriate supervision), and followed through on lab and imaging results without prompting. Nurses specifically commented to me on his responsiveness and clarity of communication. One example that stands out is a patient with a new diagnosis of metastatic cancer; Alex led a difficult goals-of-care conversation with the family with poise and empathy that exceeded the typical medical student level.

Perhaps most impressive was Alex’s teachability. He proactively sought mid-rotation feedback, implemented suggestions, and then followed up to ensure he had improved. This pattern of self-directed growth is a trait I associate with our best residents. I can recommend him to you without reservation.”

That is night-and-day. And 80% of the detail comes straight out of the structure you provided.

Handling Common Variations and Problems

What if the attending is truly too busy for three sit-down meetings?

You adapt the same structure with micro-conversations plus email.

Meeting 1 “lite”: 3–5 minutes after rounds.

“Dr. Smith, quick question—if I wanted to perform at the level of your strongest students on this rotation, what is one or two things I should focus on this week?”

Then send a thank you + recap email that evening:

“Thank you for the feedback today about tightening my presentations and anticipating overnight events. I will focus on those this week and circle back next week to see if you notice improvement.”

Meeting 2 “lite”: Another 3–5 minute corridor moment.

“I tried to implement your suggestions about [X]. Have you noticed any improvement, or is there something else I should adjust?”

Then another email summarizing and noting specific examples they mentioned.

Meeting 3 “full”: You still want to ask for the letter live if possible, even if the prior two were micro-check-ins.

If live is impossible, a well-constructed email can work, but do not skip the earlier steps.

What if they say “I do not know you well enough”?

Believe them. Do not push.

You can respond:

“I appreciate your honesty. I only want letters from people who can comment in depth. Are there other faculty you think observed my work more closely whom you would recommend I approach?”

Then salvage the relationship by still sending a brief thank-you email at the end of the rotation.

What if you are premed and only shadowing?

Shadowing alone is weak for letters because there is almost no clinical responsibility. You must add substance:

- Ask to help with small but real tasks (literature searches, patient education handouts, small QI project).

- Schedule at least one explicit feedback meeting where you discuss what you are learning and how you have contributed.

- Your packet should emphasize your initiative, reliability, and insight rather than direct patient care.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Start Rotation |

| Step 2 | Meeting 1: Positioning |

| Step 3 | Perform and Implement Feedback |

| Step 4 | Meeting 2: Evidence and Growth |

| Step 5 | Final Week |

| Step 6 | Meeting 3: Ask for Strong Letter |

| Step 7 | Send Letter Packet |

| Step 8 | Attending Writes Detailed Letter |

Quick Comparison: Passive vs. Three-Meeting Approach

| Aspect | Passive Approach | Three-Meeting Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Timing of letter request | [Last day / by email later](https://residencyadvisor.com/resources/letters-of-recommendation/lastminute-mentor-shopping-why-it-sabotages-your-med-school-letters) | Planned, last week in person |

| Feedback during rotation | Rarely obtained | [Structured at least twice](https://residencyadvisor.com/resources/letters-of-recommendation/structured-mentor-meetings-agendas-that-lead-to-powerful-recommendations) |

| Attending’s memory of you | Fuzzy, generic | Anchored to clear examples |

| Letter specificity | Low | High |

| Risk of weak letter | High and unknown | Lower and mostly visible |

Final Steps: Do Not Skip the Follow-Through

Two last pieces students ignore.

Clear deadlines and systems

When the attending agrees:

“The earliest school deadline is October 1. Would it be helpful if I send a reminder two weeks before that?”

Then actually send the reminder. Calendars exist for a reason.

Thank-you and updates

Once the letter is in:

- Send a sincere thank-you note or email.

- Later, send a short update: “I was accepted to X and will be starting there this fall. Your letter played a real role in this.”

That is how you build mentors for life, not single-use letter writers.

FAQs

1. How many meetings is realistic on a 2-week rotation?

Compress them. Do Meeting 1 in the first 1–2 days, Meeting 2 around day 6–7, and Meeting 3 near the end. Your “meetings” might be 5-minute stand-ups instead of formal sit-downs, but the structure stays identical: early expectations, mid-rotation feedback + examples, final week ask + packet.

2. Should I ask more than one attending for letters from the same rotation?

Yes, if you worked with multiple attendings who truly saw your work. Different voices add credibility. Just avoid asking someone who only interacted with you for a day or two. Aim for 2–3 strong letters total for med school; you do not need every attending you meet to write one.

3. What if I already finished the rotation and did none of this?

You are working uphill, but it is not hopeless. Pick the attending who saw you the most. Send a concise email:

- Remind them who you are and when you rotated.

- Mention a specific patient/case to jog their memory.

- Ask if they can write a strong, detailed letter.

- Attach a very similar packet (themes + examples), even if it is based on your own recollection.

Just understand: this retrofit version will almost never be as strong as if you had done the three-meeting approach in real time.

4. Is it pushy to give them a “summary of my strengths and cases”?

No, if you frame it correctly and keep it factual. You are not writing your own letter; you are providing raw material. As long as you:

- Use neutral language (“I did X” rather than “I am outstanding at X”).

- Present real, verifiable examples.

- Make it optional (“if helpful, I can provide…”).

Most attendings will be relieved you did the heavy lifting.

Key takeaways:

- Do not “hope” for good letters. Engineer them with three planned interactions.

- Use those meetings to create a narrative arc: baseline → feedback → growth → ask.

- Make it brutally easy for the attending to write a specific letter by giving them accurate, concrete examples in a tight packet.