Why Your Research Profile Matters as an IMG in Psychiatry

For an international medical graduate, psychiatry residency in the US is increasingly competitive. Programs want evidence that you understand the US academic culture, can think critically about evidence, and will contribute to scholarly work during residency. A strong research profile can:

- Offset older year of graduation or limited US clinical experience

- Demonstrate commitment to psychiatry (vs. appearing “specialty undecided”)

- Show that you can work in teams, meet deadlines, and complete projects

- Strengthen your psych match application at research-oriented programs

In psychiatry, research is not just for academic careers. Even community programs value applicants who can interpret literature, use evidence-based treatments, and contribute to quality improvement (QI). For an IMG residency guide tailored to psychiatry, understanding how to build a practical, realistic research portfolio is essential.

This article focuses on how an international medical graduate can strategically build a research profile to support a psychiatry residency application—whether you are still in medical school, in a gap year, or already graduated.

Understanding Research Expectations in Psychiatry Residency

Programs vary widely in how much they emphasize research, but almost all value some scholarly activity. Understanding what programs look for helps you plan efficiently.

What “Counts” as Research for Residency?

In the context of psychiatry residency, “research” is broader than many IMGs initially think. It includes:

Original research

- Clinical trials

- Observational or chart review studies

- Survey-based studies (e.g., attitudes toward mental health, burnout)

- Qualitative research (interviews, focus groups)

Quality improvement (QI) and patient safety projects

- Reducing inpatient seclusion/restraint use

- Improving follow-up rates after discharge from psychiatric units

- Increasing screening for depression or suicide risk in primary care

Scholarly writing

- Case reports and case series (e.g., rare side effects of antipsychotics)

- Narrative or systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- Book chapters or guideline contributions

Educational research / scholarly education projects

- Curriculum development projects (e.g., teaching motivational interviewing)

- Evaluating an educational intervention for medical students

Conference presentations & posters

- Local, regional, national, or international psychiatric conferences

Programs do not require you to have done everything on this list. But a combination—especially if clearly psychiatry-focused—builds a strong, coherent research story.

How Many Publications Are “Enough”?

Applicants often ask, “how many publications needed to match psychiatry?” There is no universal number. However, patterns from successful IMG applicants and NRMP data suggest:

Competitive academic psychiatry programs often see:

- 3–6+ scholarly items (including posters, abstracts, and papers)

- At least 1–2 items clearly related to psychiatry or mental health

Well-rounded community programs often see:

- 1–3 scholarly items (case report, QI project, or poster) are usually sufficient if the rest of the application is strong

More important than the raw count is whether your work is:

- Relevant to psychiatry or behavioral health

- Completed to at least a finished poster, abstract, or paper

- Understandable (you can explain your role, methods, and results)

If you are starting from zero, aim to build a coherent portfolio with at least one substantial project plus a few smaller ones, rather than chasing a random high number of low-quality publications.

Choosing the Right Psychiatry Research Opportunities as an IMG

Different IMGs have very different starting points. Your strategy depends on your current situation.

Scenario 1: You Are Still in Medical School (Home Country)

You have a powerful advantage: access to patients, data, and university infrastructure.

Priorities:

Identify a mentor with a psychiatry connection

- A psychiatry faculty member, a neurologist with mental health interest, or a public health researcher working on addiction, suicide, trauma, etc.

- Ask directly: “I am interested in a psychiatry residency in the US. Could I assist with any ongoing mental health or neuroscience-related research?”

Start with feasible, “finishable” projects

- Retrospective chart review on depression admissions, psychotropics in the elderly, etc.

- A short survey of medical students’ or residents’ attitudes toward mental illness

- Case reports of interesting psychiatric or neuropsychiatric presentations

Try to link your medical school thesis/dissertation to psychiatry if possible

- Topics like substance use, suicide prevention, child development, dementia, psychosomatic disorders, or mental health services research all read as “psychiatry-related” to US programs.

Aim for at least one conference presentation before graduation

- Local or national conferences in your country still count.

- Document them properly on your CV and ERAS as presentations/abstracts.

Scenario 2: You Are an IMG Graduate in Your Home Country (No US Visa Yet)

You may have limited access to formal research infrastructure, but you still have options.

Options to pursue:

Remote collaboration with faculty from your home institution

- Propose a retrospective study based on existing records if you can access de-identified data.

- Offer to help with data cleaning, literature review, or manuscript drafting.

Online, remote research roles

- Many US- or EU-based researchers work with international collaborators for systematic reviews or meta-analyses.

- Look for psychiatry, psychology, or neuroscience projects via LinkedIn, ResearchGate, or through alumni networks.

Case reports and reviews

- If you are seeing patients clinically, you can write up unusual psychiatric presentations or psychotropic side effects.

- Narrative reviews on mental health issues prevalent in your region (e.g., stigma, post-conflict PTSD, addiction patterns) can be valuable if you collaborate with an experienced author.

Open data projects

- Use publicly available datasets (e.g., WHO mental health survey data, national health surveys) to do secondary analyses under remote supervision.

Scenario 3: You Are in the US on a Visitor or Research Visa

This is often the most powerful position for building a strong research portfolio for the psych match.

Priorities:

Secure a structured research position

- Psychiatry departments at academic centers often have unpaid/volunteer research assistant positions that can lead to authorship.

- Search university psychiatry department websites for “research assistant,” “volunteer research,” “clinical research coordinator,” or “postdoctoral fellow” (for those with PhDs).

Align with psychiatry or closely related fields

- Addiction medicine, behavioral neurology, sleep medicine, psychosomatic medicine, child and adolescent psychiatry, geriatric psychiatry, and consultation-liaison psychiatry all align well.

Clarify your role and timeline

- Ask potential supervisors:

- “What kinds of projects can I realistically finish in 6–12 months?”

- “What is the path to authorship or conference presentations?”

- Ask potential supervisors:

Leverage US research for letters of recommendation (LoRs)

- A US psychiatry research mentor who knows you well can write a very impactful LoR, particularly emphasizing your analytical thinking, reliability, and teamwork.

Building a Step‑by‑Step Research Plan for IMGs Targeting Psychiatry

To avoid feeling overwhelmed, think in terms of phases. Below is a practical roadmap.

Phase 1: Foundation – Learn the Basics of Research

If you are new to research, start with skills:

Take structured courses (free or low-cost)

- Coursera / edX: courses on “Clinical Research Methods,” “Statistics with R,” or “Epidemiology.”

- NIH or CITI: research ethics and Good Clinical Practice (GCP).

- Try to obtain certificates you can list in ERAS under educational experiences.

Read psychiatry journals regularly

- Start with: American Journal of Psychiatry, JAMA Psychiatry, British Journal of Psychiatry, and specialty areas like addiction or child psychiatry depending on your interest.

- Aim for one article per week; take notes on: research question, design, main outcomes, limitations.

Learn reference management tools

- Zotero, Mendeley, or EndNote Basic—important for literature reviews and manuscripts.

Get familiar with common study designs in psychiatry

- Case-control, cohort, RCT, cross-sectional surveys, qualitative methods (interviews, focus groups).

Phase 2: Low‑Barrier Wins – Start Small but Finish

You do not need to start with randomized trials. Early wins build momentum and confidence.

Good starter projects for an IMG in psychiatry:

Case report + literature review

- Example: A rare extrapyramidal reaction to an atypical antipsychotic, or an unusual presentation of OCD.

- Steps:

- Obtain patient consent and de-identify information.

- Search the literature and summarize what is known.

- Co-author the write-up with a faculty supervisor.

- Target journals: lower-impact psychiatry journals or case report journals.

Simple retrospective chart review

- Example: Describing antipsychotic prescribing patterns on your inpatient unit.

- Steps:

- Define a narrow question and minimal dataset.

- Obtain ethics approval (IRB/ethics committee).

- Use Excel/SPSS for simple descriptive stats.

- Present findings as a poster at a local or regional meeting.

Short survey study

- Example: Prevalence of burnout among psychiatry residents or mental health attitudes among medical students.

- Use free tools (Qualtrics, Google Forms) if allowed by your institution.

- Start with small samples but aim for clear, interpretable results.

The goal in this phase: Produce 1–2 complete outputs (e.g., case report + conference poster) to prove to yourself and future mentors that you can complete projects.

Phase 3: Focus and Depth – Align Research With Psychiatry Themes

Once you have early wins, deepen your focus in psychiatry-related domains. Choose a few thematic areas that align with both your interests and residency programs:

- Common, high-impact psychiatry topics

- Depression, anxiety, psychosis, bipolar disorder

- Suicide prevention and risk assessment

- Substance use disorders and addiction medicine

- Trauma, PTSD, refugees and immigrant mental health

- Geriatric psychiatry: dementia, delirium

- Child & adolescent psychiatry: ADHD, autism, school-based interventions

- Cultural psychiatry and stigma

Choosing a theme helps create a coherent narrative across your research, personal statement, and interview answers.

Example of a coherent narrative:

- Research: Survey on depression stigma among medical students; case report on late-life depression; review article on suicide risk in the elderly.

- Personal Statement: Emphasis on improving recognition and treatment of depression in under-resourced populations.

- Interview Answers: Consistent discussion of how your research shaped your understanding of mood disorders and suicide risk.

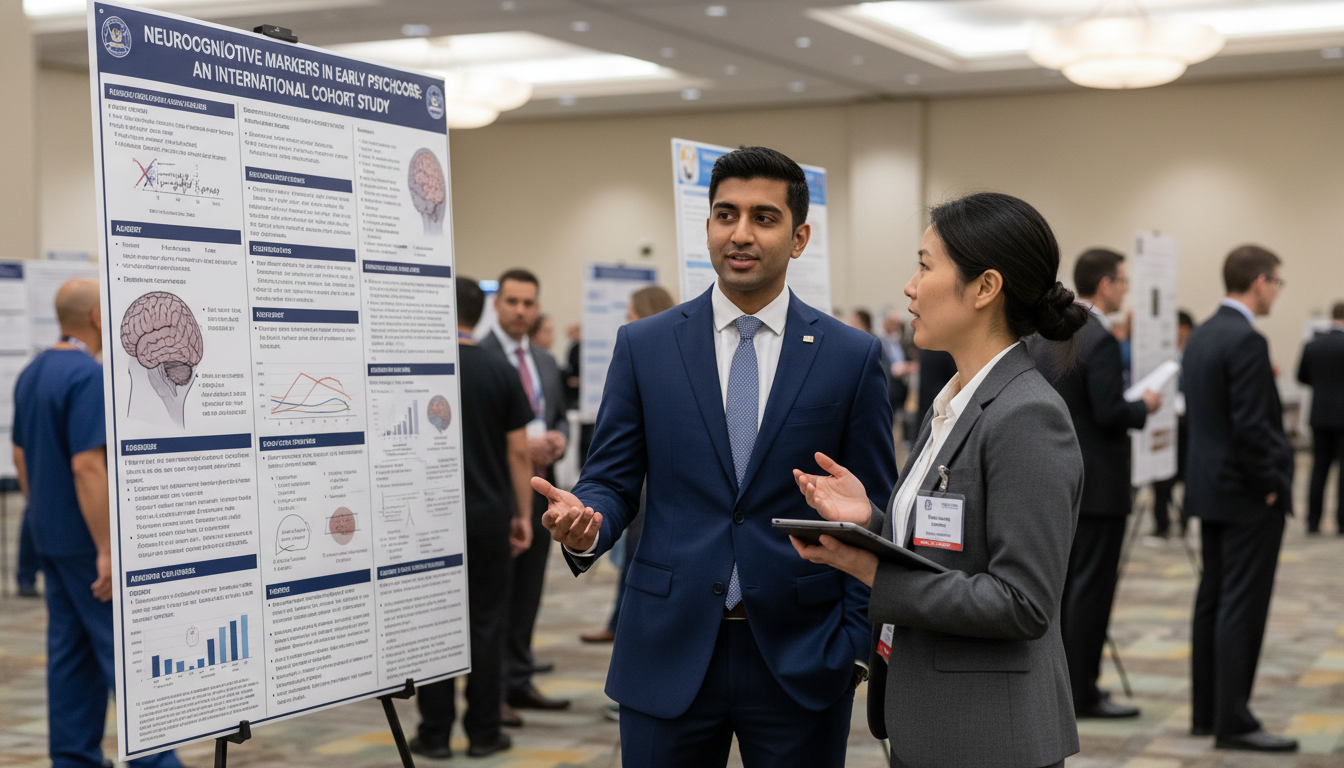

Phase 4: Visibility – Turn Work Into Tangible Outputs

Residency programs cannot see your “ongoing” projects unless they lead to visible outputs. Strategically convert your efforts into:

Publications for the match

- Original articles (even in smaller journals) carry weight.

- Case reports and narrative reviews are achievable starter publications.

- Systematic reviews/meta-analyses are impressive but methodologically demanding; do them under strong supervision.

Posters and oral presentations

- Present at:

- National psychiatry meetings (e.g., APA, AACAP, specialty societies)

- Regional or state psychiatric society meetings

- Hospital or departmental research days

- Even if the conference is in your home country, list it clearly (with location and date).

- Present at:

Online profile

- Create a Google Scholar or ResearchGate profile with your publications.

- Keep an updated LinkedIn with a clear “aspiring psychiatry resident” headline and brief description of your research.

Maximizing Impact: How to Present Your Research in the Psych Match

Having research is not enough; how you present it in your application and interviews is critical.

Curating Your CV and ERAS Application

Group psychiatry-related items together

- Emphasize mental health, neurosciences, addiction, child/adolescent topics.

- Put most psychiatry-relevant work higher in the list if possible.

Be clear about your role

- Use action verbs: “Designed survey,” “Performed data analysis,” “Drafted introduction and discussion,” “Coordinated data collection.”

- Programs want to know you were more than “name on a paper.”

Include all legitimate scholarly activities

- Publications (accepted, in press, or published)

- Submitted manuscripts (clearly labeled as “submitted”)

- Abstracts and conference posters

- Theses or dissertations (if research-based and relevant)

- Significant QI projects with defined outcomes (e.g., reduced readmissions, improved screening rates)

Avoid exaggerating or listing unverified “in progress” work as if already accepted.

Discussing Research in Personal Statements

Your personal statement is not a research paper, but it’s a good place to:

- Highlight one or two key projects that shaped why you chose psychiatry.

- Explain how research changed your clinical perspective, e.g.:

- “Working on a study of suicide attempts among adolescents showed me the importance of early intervention and accessible community resources.”

- Show humility and growth—describe challenges, what you learned from negative or null results, or from a rejected manuscript.

Avoid dense statistical jargon. Focus on what the research taught you about patients, psychiatry, and your professional identity.

Talking About Research in Interviews

Program directors and faculty want to know that you:

- Understand your study’s research question, methods, results, and limitations

- Had a real, substantive role in the project

- Can connect your research to real-world psychiatric practice

Prepare concise, structured answers:

“Tell me about your research”

- Prepare a 2–3 minute narrative about your most important project:

- Background & question

- Methods (in simple terms)

- Key results

- What you learned

- How it influenced your interest in psychiatry

- Prepare a 2–3 minute narrative about your most important project:

“What was your role?”

- Be specific: data collection, literature review, writing sections, statistical analysis (specify level).

“What were the limitations?”

- Show maturity: small sample size, single-center design, recall bias, lack of control group, etc.

“Do you plan to continue research in residency?”

- Answer affirmatively, aligning with program focus:

- “I hope to continue working in mood disorders and suicide prevention, possibly through quality improvement projects in the clinic or inpatient unit.”

- Answer affirmatively, aligning with program focus:

Ethical and Strategic Considerations for IMGs in Psychiatry Research

Avoiding Predatory Journals and Questionable Practices

As pressure increases, some IMGs are tempted by “quick publication” offers. This can damage your reputation.

Red flags for predatory or low-credibility publishing:

- Emails inviting you to publish in unfamiliar journals with excessive publication fees

- Promise of “guaranteed acceptance in 7 days”

- Journal is not indexed in PubMed, Scopus, or Web of Science, and has very little verifiable editorial board information

Programs increasingly recognize these journals. Instead, aim for:

- Specialty psychiatry or general medical journals with standard review processes

- Reputable open-access journals indexed in major databases

- Faculty guidance before submission

Authorship Ethics

Authorship should reflect real contribution to:

- Concept/design

- Data acquisition or analysis

- Manuscript drafting or critical revision

- Final approval and accountability

Do not:

- Pay for “gift authorship”

- Add your name to papers you did not work on

- List “accepted” papers without actual documentation

If asked in an interview and you cannot explain the paper or your role, it raises red flags.

Balancing Time: Research vs. Other Application Components

For the IMG residency guide mindset, remember: research strengthens your profile but does not replace the basics.

You still need:

- Competitive USMLE scores (or OET/other as relevant to your pathway)

- US clinical experience (USCE), especially in psychiatry (observerships, externships, clerkships)

- Strong letters of recommendation, preferably from US psychiatrists

- A well-written personal statement and polished ERAS application

If your time is limited (e.g., 1 year), a realistic allocation might be:

- 40–50%: USCE and clinical performance

- 20–30%: Research and publications for match

- 10–20%: Exam preparation (if still needed)

- Remaining: Networking, personal statement, and logistics

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. I have zero research experience. Is it still possible to match into psychiatry as an IMG?

Yes, it is possible, especially at community-focused programs, but research can significantly strengthen your profile. If you have no research, try to complete at least one small, psychiatry-related project (e.g., a case report or QI project) before applying. Even minimal but well-explained experience demonstrates initiative, curiosity, and evidence-based thinking.

2. How many publications do I need as an IMG for psychiatry?

There is no strict cutoff. Many successful IMG applicants have 1–3 meaningful items (case reports, posters, small studies). Highly academic programs may favor those with 3–6+ psychiatry-related outputs, but quality and relevance matter more than sheer number. Focus on completing a few well-executed projects rather than accumulating many superficial ones.

3. Does research outside psychiatry (e.g., internal medicine) still help my psych match?

Yes, non-psychiatry research can still help, especially if it demonstrates core skills: data analysis, teamwork, perseverance, writing. However, try to develop at least some mental health–related work (e.g., depression in chronic illness, delirium, adherence, quality of life) so that your profile clearly aligns with psychiatry. During interviews, connect what you learned in non-psychiatric research to psychiatric practice.

4. I worked as a research assistant but have no publications yet. Is that useful?

Yes. Experience as a research assistant still counts, provided you describe your concrete responsibilities and skills gained. On your CV and in ERAS, list:

- Project titles and supervisors

- Your specific tasks (data collection, patient interviews, chart reviews, database management, etc.)

- Any abstracts, posters, or manuscripts in progress

In interviews, explain what you learned about study design, ethics, teamwork, and patient care. Programs know that not every project leads to quick publications, especially large longitudinal studies.

By understanding program expectations, choosing feasible psychiatry-focused projects, and presenting your work effectively, you can build a compelling research profile as an international medical graduate. Thoughtful, ethical, well-explained research—whether small or large—can significantly enhance your chances in the psychiatry residency match and lay the foundation for a career that integrates both clinical care and scholarly inquiry.