Most residency applicants are misreading their own research metrics—and it shows on their CVs and in their interviews.

Let me be blunt. Program directors are not scrolling through your Google Scholar profile doing bibliometrics. They glance at your CV for 20–30 seconds and form an impression. The way you present (or over‑present) h‑index, citation counts, and journal impact factor can help you or quietly hurt you.

You are not applying for a tenure‑track job. You are applying to be a resident. Different rules.

Let me break this down very specifically.

1. What These Metrics Actually Mean (In Real Life)

First, definitions. Then I will tell you what actually matters for residency.

H‑Index: The Most Overrated Number on Student CVs

H‑index is defined as: you have index h if h of your papers have at least h citations each.

So:

- h‑index 3 → at least 3 papers with ≥3 citations each

- h‑index 7 → at least 7 papers with ≥7 citations each

For a seasoned attending, that is one thing. For a medical student or PGY‑1? Honestly, it is close to noise.

Why it is mostly useless at the student level:

- Strongly biased by field (oncology vs radiology vs family medicine)

- Strongly biased by time in research (a PhD‑then‑MD will dwarf an MD‑only classmate)

- Punishes early‑stage authors regardless of quality

- Extremely sensitive to one or two older projects that happened to get traction

I have seen MS4s proudly list “H‑index: 2” in bold on their CV. On an application with two posters and one middle‑author retrospective. That reads as misunderstanding, not strength.

H‑index for students is descriptive at best:

- It tells me you have at least a few things out there that someone has cited.

- It does not differentiate a truly productive, engaged researcher from someone who landed on one large team paper.

Citations: What They Signal (And What They Don’t)

Total citation count is simply: how many times other papers have referenced your work.

High citations can mean:

- The work is relevant, high‑impact, or in a fast‑moving field.

- The paper is in a big consortium or multicenter trial.

- The paper addresses a standard method or dataset that everyone uses.

- Or: the paper is in a controversial area that gets argued over.

Low citations can mean:

- The topic is niche.

- The paper is new (under 1–2 years).

- The journal has limited reach.

- Or: the paper just did not land.

For residency evaluation, raw citation numbers are dangerous. A fourth author on a 600‑citation NEJM trial is not automatically more “research serious” than a first author on a 5‑citation education paper that was entirely their own idea.

Citations are context‑dependent. Without context, numbers mislead.

Impact Factor: The Most Abused Number on CVs

Journal Impact Factor (JIF) is:

- Average number of citations received in a given year by articles published in that journal in the previous two years.

So an impact factor of 10 means: on average, papers in that journal from the prior two years got 10 citations last year.

Problems:

- It is a journal‑level metric, not an article‑level metric. Your specific paper might be ignored in an “IF 30” journal or heavily cited in an “IF 1.5” journal.

- It varies wildly by field.

- It is gameable (editorial policies, review articles, etc.)

- The number is often misremembered or rounded up by applicants.

That said, PDs and faculty do have a rough mental tiering:

- “Big‑name general medical journals” (NEJM, JAMA, Lancet, BMJ)

- High‑tier specialty journals

- Solid mid‑tier specialty / subspecialty journals

- Low‑tier or questionable journals

Impact factor correlates somewhat with this tiering but is not the whole story.

2. How Program Directors Actually Look at Your Research

Stop imagining a committee arguing whether your h‑index of 3 vs 4 is competitive. That conversation does not happen.

Here is what actually happens when research is reviewed.

The 10‑Second Scan

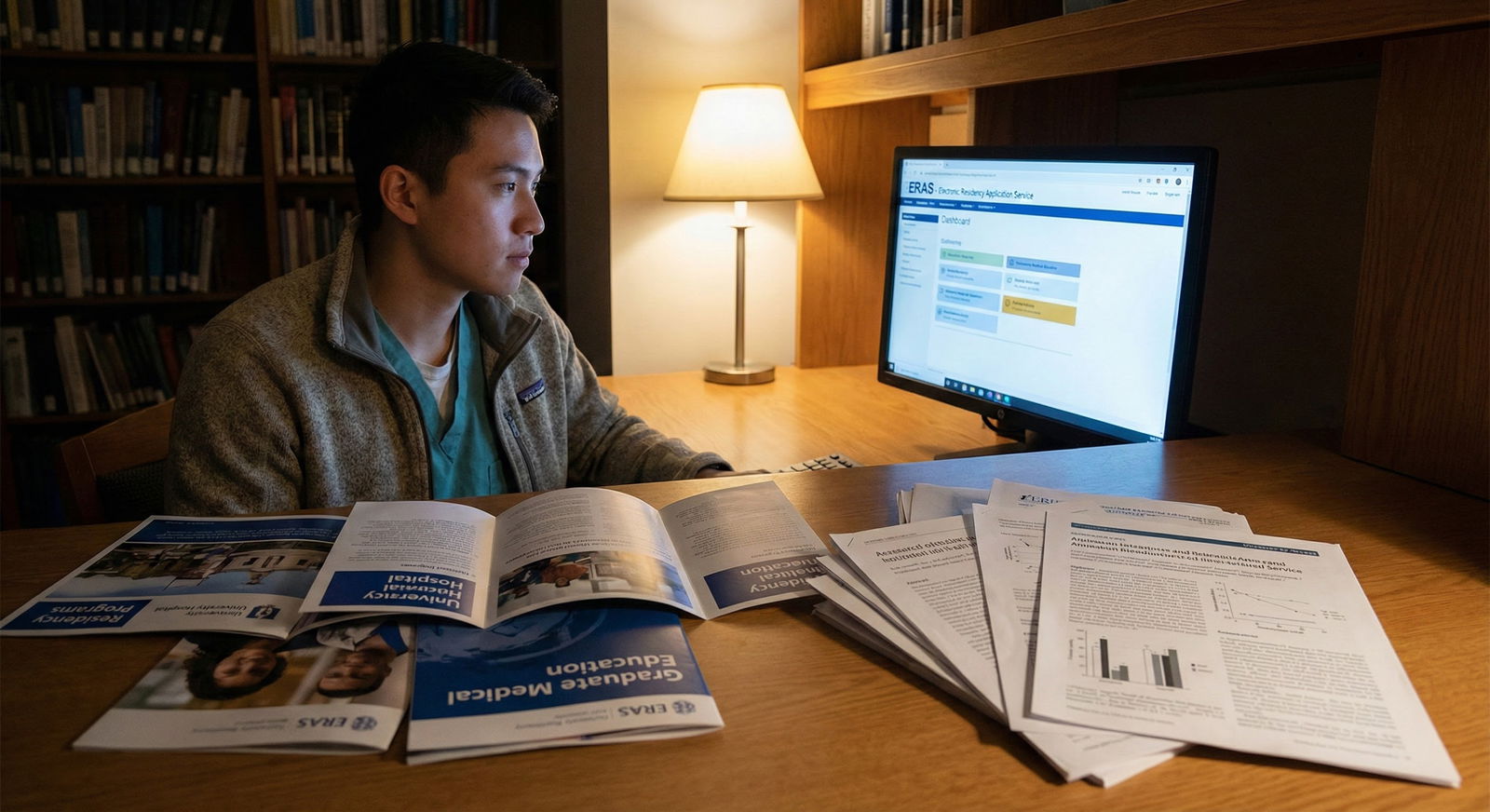

A PD (or faculty reviewer) opens your ERAS application. They skim:

- Number of PubMed‑indexed papers

- Number of abstracts/posters/oral presentations

- Any obvious first‑author or last‑author roles

- Any recognizable journals (either name‑brand or respected specialty)

- Evidence of consistency (research over several years, not just one summer)

They ask themselves a few quick questions:

- Did this person actually do research or just list their name on one team paper?

- Is their research connected to my specialty?

- Do they seem like someone who can complete projects?

They do not think: “Ah yes, an h‑index of 4, very impressive.”

What Matters More Than Metrics

Here are the signals that actually matter:

Authorship position

- First author = you did the heavy lifting: idea, data collection, writing.

- Middle author = fine, collaborative role, sometimes minor.

- Last author (for a student) is rare and often indicates significant leadership.

Type of work

- Original research (prospective or retrospective)

- Systematic reviews / meta‑analyses

- Narrative reviews / book chapters

- Case reports / series

- QI projects

Specialty relevance

- Applying to ortho: ortho, sports med, biomechanics, MSK imaging, etc.

- Applying to psych: psychiatry, neurology, behavioral science.

Productivity pattern

- Did you start early and consistently contribute over time?

- Or do you have a pile of 5 papers all from one three‑month summer?

What your letter writers say

- “This student independently drove a project to completion.”

- “They were responsible for data analysis and drafting the manuscript.”

Metrics are supporting characters. Not the lead.

3. When H‑Index, Citations, and Impact Factor Actually Help You

Now, to be fair, there are situations where these numbers can strengthen your story—if handled correctly.

Highly Research‑Heavy Fields and Tracks

In certain specialties and specific programs, research metrics carry more weight:

- Radiation oncology

- Dermatology

- Neurosurgery

- Plastic surgery

- ENT

- Physician‑scientist / research tracks in IM, pediatrics, neurology, etc.

In those contexts, metrics can be used as shorthand:

- H‑index in the high single digits or above for a student is notable.

- A first‑author paper with >50 citations before graduation stands out.

- Multiple publications in clearly high‑impact journals in the target specialty.

But even here, nuance matters:

- A derm applicant with 12 mid‑tier, relevant, first‑author papers and modest citations is often more attractive than someone with 1 middle‑author NEJM paper plus fluff.

Showing Long‑Term Research Identity

If your story is: “I am aiming for an academic research career,” metrics become a bit more relevant as supporting evidence.

For example:

- MD/PhD or post‑doc before med school

- A gap year (or more) fully devoted to research

- A research track application with explicit plans for K‑award type funding

Then it is acceptable to signal:

- “H‑index 9, 450+ citations, 3 first‑author publications in [field].”

Those numbers say: you are not brand new to research. You have been at it for a while.

Internal Comparisons in Big Research Groups

Inside a large research group (for LORs and internal selection), mentors might look at h‑index or citations to decide:

- Who gets priority for projects

- Whose CV to push hardest for a competitive spot

This is not usually visible to you, but it happens.

For your residency application, the takeaway is simpler: if you genuinely have unusually strong metrics for a student, you can mention them briefly and accurately. They should support, not replace, the narrative of what you actually did.

4. How to Present These Metrics on Your CV (Without Making Yourself Look Naive)

This is where most applicants go wrong. The problem is not the number itself. It is where and how you put it.

Rule 1: Do Not Lead With Metrics

The “Research” section of your CV should focus on:

- Projects

- Roles

- Outcomes (papers, posters, talks)

- Ongoing work

You do not want your first research line to be:

- “H‑index: 3, Citations: 27”

That looks try‑hard and uncalibrated.

Instead, build the foundation:

- List publications in standard format (PubMed style).

- Make authorship and journal clear.

- Highlight first‑author roles typographically if desired (bold your name).

If you really want to include metrics:

- They belong in a short “Research summary” subsection or at the very end of research, not front‑and‑center.

For example:

“Research summary: 7 peer‑reviewed publications (3 first‑author), 4 oral presentations, 5 posters.”

If your metrics are truly exceptional for your level: “Research summary: 9 peer‑reviewed publications (4 first‑author, h‑index 6, ~180 citations), 3 invited oral presentations.”

Short. Factual. Not overhyped.

Rule 2: Never Round Up or Guess Impact Factors

Do not list:

- “Journal of X (Impact Factor ≈ 7.5)”

- “Published in multiple high‑impact journals (IF > 5)”

This reads as padding. Faculty know the field; if the journal is truly high‑impact, they will recognize it. If they do not recognize it and you call it “high‑impact,” you lose points.

The cleanest approaches:

- Either do not list impact factors at all (my preference for 95% of applicants), or

- Only reference impact factor in a very narrow, clearly true context, such as:

“First‑author paper in a top‑quartile cardiology journal.”

You can use “top‑quartile” or “top‑tier” if that is verifiably true by Journal Citation Reports or Scimago rankings. Otherwise, skip it.

Rule 3: Avoid Citation Counts for Single Papers On the CV

Writing:

- “Smith J, Lee T, You A, et al. Some Title. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:123–130. (Citations: 87)”

on each line screams “I am trying too hard to impress you with numbers.” It also clutters the CV visually.

If citation numbers are unusually strong across multiple papers:

- Summarize them in a single line:

“Collectively, these works have been cited >350 times (Google Scholar, accessed June 2026).”

And then stop.

Rule 4: Be Very Clear About Your Role

No metric compensates for unclear authorship contribution. Programs care more about what you did than how many times the group was cited.

In interview prep, you should be able to say, for each major paper or project:

- What was the hypothesis or question?

- What was your specific role? (Study design, data collection, statistical analysis, drafting introduction/discussion, IRB submission, etc.)

- What did you learn?

- What changed your practice or your thinking?

An applicant with modest metrics but crystal‑clear descriptions of contribution will consistently outperform the applicant with strong metrics but vague “I helped” answers.

5. Smart Ways to Use Metrics in Personal Statements and Interviews

Numbers can help if they are used to support a clear narrative. They should not be the narrative.

In Your Personal Statement (If You Are Research‑Oriented)

Most applicants do not need to mention h‑index or citations in a personal statement. If you are explicitly pitching an academic trajectory, you might.

Bad version:

“I have an h‑index of 4 and 3 first‑author papers and over 100 citations, which show my commitment to research.”

Good version:

“Over the past five years, I have completed several projects in inflammatory bowel disease, including four first‑author manuscripts and a prospective cohort study that has now been cited over 80 times. More important than the numbers, these projects trained me to design feasible studies, work closely with statisticians, and respond constructively to peer review.”

See the difference? Numbers are context, not the main character.

In Interviews

Interviewers will often ask:

- “Tell me about your research.”

- “Which project are you most proud of?”

- “What did you do for this publication?” (pointing at your CV)

If someone brings up metrics, fine:

- “That paper has been cited a bit more than I expected, around 60 times so far, probably because it addressed a common clinical decision‑point in stroke care.”

Then pivot back to content:

- “But the main impact for me was learning how to handle messy retrospective data and reconcile conflicting chart entries.”

If you ever find yourself talking more about h‑index than about hypotheses, methods, and what you actually did, you are off track.

6. Field‑Specific Realities You Need To Respect

Not all specialties judge research metrics the same way. Pretending otherwise makes you look out of touch.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Radiation Oncology | 9 |

| Dermatology | 8 |

| Neurosurgery | 8 |

| Internal Medicine | 5 |

| Emergency Medicine | 3 |

| Family Medicine | 2 |

High‑Research, High‑Metrics Fields

Radiation oncology, derm, neurosurgery, plastics, ENT, some IM subspecialty tracks: here, more granular research evaluation happens.

In these fields:

- PDs and faculty are used to skimming PubMed.

- They may recognize specific landmark papers or big‑name labs.

- They know roughly which journals matter in their niche.

Metrics can:

- Help prevent your work from being underestimated (“No, this is not a small paper—it is one of the main references in this area.”)

- Signal that your work has had traction in the community.

But again, they look secondary to:

- Authorship

- Relevance to the field

- Sustained involvement

Clinically Heavy, Less Research‑Driven Fields

EM, FM, psych (outside of research tracks), community‑based IM or surgery programs:

- A few solid projects or a couple of publications are usually enough to “check the box.”

- What you learned from research, how you work on a team, and your clinical evaluations will crush your h‑index in importance.

If you spend half your ERAS application trying to convince an FM program that your impact factor is high enough, you are wasting space and potentially signaling poor judgment.

7. Common Mistakes and How To Fix Them

Let me run through the patterns I see over and over.

Mistake 1: Treating Metrics as the Centerpiece of Your Application

Symptom:

- “H‑index: 4” at the top of the CV, big bolded line.

- Personal statement with more numbers than ideas.

Fix:

- Reframe your research as narrative: problem → your role → outcome.

- Push metrics to a brief summary line, if you use them at all.

Mistake 2: Overstating Journal Prestige With Dubious Impact Factor Claims

Symptom:

- Listing inflated or outdated IFs.

- Calling a mid‑tier journal “high‑impact” to people who publish in it regularly and know its real standing.

Fix:

- Either omit impact factors or use conservative, accurate descriptors like “respected specialty journal” only when clearly true.

- Trust that faculty know their field’s journals.

Mistake 3: Cherry‑Picking Citations for a Single Paper To Look Impressive

Symptom:

- One big paper with 400 citations, everything else anemic, but application leans heavily on the big number.

Fix:

- Acknowledge the big paper, but spend equal or more time on projects where you had major responsibility, even if citations are lower.

- In interviews, emphasize your role over the number of times the work was cited.

Mistake 4: Ignoring Time‑Lag and Field Effects

Symptom:

- Comparing your 6‑month‑old paper’s 2 citations to someone else’s 10‑year‑old paper’s 200 citations as if they are equivalent.

Fix:

- If you mention citations, contextualize timing (“published 8 months ago, already being cited in several guidelines” or “recent publication, too early to assess citations”).

Mistake 5: No Internal Consistency

Symptom:

- Credential section says “10 publications,” research summary says “7 publications,” and Google Scholar shows 5.

Fix:

- Decide on a consistent definition (peer‑reviewed, PubMed‑indexed, etc.).

- Use one number and annotate if needed:

“7 peer‑reviewed, PubMed‑indexed articles; 3 additional under review or in press.”

8. Concrete Examples: How To Format This Correctly

Let me give you specific, copy‑able structures.

Example: Research Section for a Moderate‑Research Applicant

Research Summary

- 5 peer‑reviewed publications (2 first‑author)

- 3 oral presentations, 4 posters at national meetings

Publications

YourLastName A, Mentor B, Colleague C. Title. J Hosp Med. 2024;19(3):123‑130.

Role: First author; conceived study, collected data, performed initial analyses, drafted manuscript.YourLastName A, et al. Title. Acad Emerg Med. 2023;30(9):789‑796.

Role: Second author; contributed to data collection and revision of manuscript.

No metrics listed. Clean, focused on role and output.

Example: Research‑Track Applicant With Strong Metrics

Research Summary

- 11 peer‑reviewed publications (5 first‑author) in pulmonary and critical care medicine

- h‑index 7; ~260 citations (Google Scholar, June 2026)

- 4 national oral presentations, 2 invited talks

Publications

[list them as normal, no citation numbers per paper]

You let the summary carry the metric signal. You keep the rest uncluttered.

9. Quick Comparison: What Programs Care About vs What Students Obsess Over

| Aspect | Programs Actually Prioritize | Applicants Commonly Obsess Over |

|---|---|---|

| Authorship position | High (first‑author vs middle) | Medium |

| Specialty relevance | High | Low–Medium |

| Number of *completed* projects | High | Medium |

| H‑index | Low–Medium (only for outliers) | High |

| Total citation count | Low–Medium (context‑dependent) | High |

| Journal impact factor (exact #) | Low | Very High |

If your effort is inverted—heavy on the right column, light on the left—that is a problem.

10. How To Quickly Self‑Audit Your Use of Metrics

Before you finalize your CV and ERAS:

- Print your CV. Circle anything that is a metric: h‑index, citations, IF.

- For each circled item, ask:

- Does this materially clarify my research story?

- Or is it vanity dressing that could be removed without loss?

- Show it to a resident or fellow in your target field. Ask one pointed question:

- “Do these numbers help or distract?”

- Edit down. Err on the side of under‑using metrics rather than over‑using them.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Thinking of adding metric |

| Step 2 | Omit metric; focus on roles and outputs |

| Step 3 | Include in research summary only |

| Step 4 | Is it clearly exceptional for your level? |

| Step 5 | Does it fit in a brief summary line? |

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| MS1 | 0 |

| MS2 | 1 |

| MS3 | 3 |

| MS4 | 5 |

| PGY1 | 7 |

FAQ (Exactly 4 Questions)

1. Should I include my h‑index on my residency CV at all?

Only if it is clearly above average for a student in your situation and field, and even then it should go in a brief research summary line, not as a headline feature. For the majority of applicants—especially in less research‑intense fields—omitting h‑index entirely is smarter and cleaner.

2. Do program directors actually look up my citation counts or verify impact factors?

Usually not. They rely on your CV, their knowledge of journals in their field, and occasionally a quick PubMed check for a specific paper that interests them. If your numbers look wildly inflated or inconsistent, a savvy reviewer might spot‑check, but systematic verification is rare. That is exactly why you must be accurate and conservative; getting caught exaggerating is disastrous.

3. If my publications are in low‑impact journals, should I still list them?

Yes. A well‑conducted study in a modest journal still shows you can complete scholarly work. For residency, the fact of publication and your role in the project matter more than impact factor. You should not disparage your own work or hide it; just avoid over‑hyping the journal prestige on the CV.

4. How many citations or what h‑index is considered “impressive” for a residency applicant?

It depends heavily on field and background. For an MD‑only student, an h‑index above 5 or a couple of first‑author papers with >50–100 citations each is clearly notable. For MD/PhD applicants or those with several pre‑med‑school research years, expectations are higher. But remember: even “impressive” numbers are supporting evidence, not the main criterion for residency selection.

Key takeaways:

- Metrics like h‑index, citations, and impact factor are secondary signals; your actual role, authorship, and relevance to the specialty matter more.

- If you use metrics at all, keep them accurate, understated, and confined to a brief research summary—never as the centerpiece of your CV or personal statement.

- The most competitive applicants talk less about numbers and more about ideas, methods, and what they personally contributed to each project.